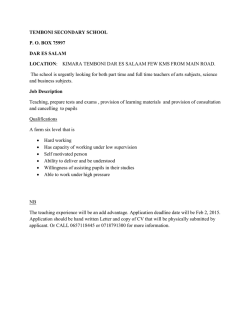

Mapa de Ubicación