Conflict of Interest and Corruption: Lessons Learned from the OECD

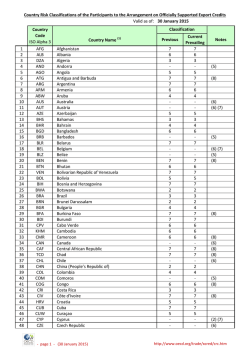

Conflict of Interest and Corruption: Lessons Learned from the OECD Countries Janos Bertok Head of Public Sector Integrity Division Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Context: Declining trust in public institutions Core principles for managing conflict of interest • OECD Principles to manage CoI and maintain trust in public institutions – Serving the public interest – Supporting transparency and scrutiny – Promoting individual responsibility and personal example – Fostering an organisational culture which is intolerant of conflict of interest Growing grey areas: how to manage effectively conflict of interest • A modern approach to conflict of interest seeks to strike a balance – Identifying risks – Prohibiting unacceptable forms of private interest – Raising awareness – Ensuring effective procedures to resolve CoI situations • 2014 OECD survey on management of Conflict of Interest reviewed the data and experiences of 31 countries Ensuring coherence – monitoring role for central body • Majority of countries have a central function to manage conflict of interest Countries with a central function responsible for the development and maintenance of the CoI policies Specific CoI policy for particular categories of public officials Staff in M inisterial c abinet/office No: 32% 23% Inspectors a t t he c entral level o f government 29% Customs officers 32% Political advisors/appointees 32% Auditors 39% Financial market regulators 39% Tax officials 39% Procurement officials 45% Senior public s ervants Slovenia Yes: 68% 48% Ministers 58% 0% 10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100% Assessing the impact of preventive measures not an exception Countries with diagnostic tools to assess the impact of CoI policies 2012 2014 Yes: 27% No: 45% Hungary Greece No: 73% Yes: 55% Implementing private Interest Disclosure: accuracy matters • Asset and private interest disclosure is an essential tool to properly identify and manage conflicts between private interest and public duties • Following the collection of disclosure forms, 63% of respondents verify receipt of the forms • Only 32% carry out audit or review the accuracy of the information Actions taken after collecting the private information for public officials in the executive branch Australia Austria Belgium Canada Chile Czech Republic Estonia Finland France Germany Greece Hungary Ireland Israel Italy Japan Korea Mexico Netherlands New Zealand Norway Poland Portugal Slovak Republic Slovenia Spain Sweden Switzerland Turkey United Kingdom United States Verifying receipt of the submitted disclosure form ● ○ ● ● ● ○ ○ ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ○ ● ● ▲ ".." ● ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ● ● ● ● ● Verifying that all required information was included in the submitted disclosure form ● ○ ○ ● ○ ○ ● ● ● ● ● ● ○ ● ○ ● ▲ ".." ● ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ● ● ○ ● ● ● For all those required to disclose private interest ▲ For some of those required to disclose private interest ○ Action is not taken Auditing or reviewing the accuracy of the information submitted in the disclosure form ● ○ ○ ● ○ ○ ▲ ○ ● ▲ ▲ ● ○ ○ ○ ● ● ▲ ".." ● ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ ● ● ○ ● ○ Disclosure of private interests: legislators set leadership example – judiciary falls much behind • The levels are determined by whether public officials are required to disclose such private interests as their assets, liabilities, income source and amount, paid and unpaid positions, gifts and previous employment and make the disclosed information public Disclosure in Executive: the higher the position the more transparency is required High level 100 90 80 70 Medium level 60 Head of t he Executive 50 40 30 Ministers or M embers of Cabinet Political Advisors / Appointees Senior Civil Servants Civil Servants Low level 20 10 0 • On average, top decision-makers have higher disclosure and public availability level of private interests. Raising awareness: from passive publication to proactive availability • 81%: Initial dissemination of CoI policies upon taking office and/or new post • 71%: Provide training • 65%: policies available online for access by public officials Integrity Framework: mainstreaming integrity measures in daily management • In addition to management of CoI, Integrity Framework fosters a culture of integrity against corruption Emerging concern: Revolving Door Restrictions on private sector employees or lobbyists being hired to fill a post in government Yes: 35% Norway No: 65% New Zealand • The main responsibility of safeguarding public interests and rejecting undue influence lies with those who are lobbied • The revolving door phenomenon continues to pose risks to the integrity of public decision making Estonia • About one third of OECD countries have restrictions in place on private sector employees or lobbyists being hired to fill a post in government Making an Integrity Framework effective • Training on integrity standards for raising awareness and build capacity for taking the right decisions Clear mechanisms to organise a training (e.g. how to train the trainer, how to decide the topics of the training course, who needs to attend, etc) • Timely advice - solving dilemmas • Internal control - identifying risk areas and effective measures for mitigation Internal auditing for compliance with integrity measures is crucial Whistleblower Protection: broadening the scope Public sector Australia Austria Belgium Canada Chile Czech Republic Estonia France Germany Greece Hungary Ireland Israel Italy Japan Korea Mexico Netherlands New Zealand Portugal Slovak Republic Slovenia Switzerland Turkey United Kingdom United States OECD24 employees consultants suppliers ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● “..” ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● “”..” ● ● ● ● ● ● Private Sector temporary employees former employees ● ● ● ● ● ● employees consultants ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Former employees Volunt eers ● ● ● ● ● ● Temporary employees ● ● ● ● ● ● suppliers ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 11 10 14 12 ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 24 16 12 21 16 16 7 Addressing grey areas: OECD integrity standards and tools • Lobbying OECD Principles for transparency and integrity in lobbying • Public procurement Recommendation of the Council on Public Procurement • Financing democracy/Political finance Framework for supporting better public policies and averting policy capture OECD Integrity Review Lobbying: an accelerated journey • In the past five years, the number of countries that have regulated lobbying practices have almost doubled Lobbying inside: Advisory group membership Public Procurement: is e-Procurement a solution? Australia Austria Belgium Canada Chile Denmark Estonia Finland France Germany Greece Hungary Ireland Italy Japan Korea Luxembourg Mexico Netherlands New Zealand Norway Poland Portugal Slovak Republic Slovenia Spain Sweden Switzerland Turkey United Kingdom United States OECD 31 Mandatory and Provided ● Not mandatory but provided ◘ Not provided □ Publishing procurement plans (about forecasted government needs) ● ◘ ● ◘ ● ● □ ◘ □ ◘ ● ● ● ◘ ◘ ● □ ● ● ● ● ◘ ● □ ◘ ◘ ◘ ◘ ◘ ● ● Announcing tenders ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ◘ ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● Provision of tender documents ● ● ● ◘ ● ◘ ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ◘ ◘ ● ◘ ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ◘ ● ● ● ● ● Electronic submission of bids (excluding by emails) ◘ ◘ ● □ ● ◘ ● ◘ ● ◘ ● □ ◘ ● ◘ ◘ ◘ ● ◘ ◘ ◘ □ ● ◘ ◘ ◘ ◘ □ ◘ ◘ ● 15 30 25 12 4 1 0 6 0 Ordering □ ◘ ◘ ◘ ● ◘ □ ● ◘ ◘ □ □ □ ● ◘ ◘ □ □ ● ◘ ◘ □ □ □ ◘ ◘ ◘ ● ◘ ◘ ● Electronic submission of invoices (excluding by emails) □ ● □ □ □ ● □ ● ◘ ◘ □ □ □ ● ◘ ◘ □ □ ● ◘ ◘ □ □ □ ● ● ● ● □ ◘ ● Expost contract management □ ◘ □ □ □ ◘ □ ◘ □ ◘ □ □ □ ◘ ◘ ◘ □ □ □ ◘ ◘ □ □ □ □ □ ◘ ● ● □ ● 26 6 10 3 4 1 15 10 7 14 10 18 e-tendering □ ◘ ● ● ● ◘ ● ◘ ◘ ◘ ● □ ● ● ◘ ◘ □ ● ◘ ◘ ◘ □ ◘ ◘ ◘ ◘ ◘ ● ◘ ◘ ● eauctions (in e-tendering) □ □ □ □ □ ◘ ◘ ◘ ◘ ◘ ● □ ◘ ◘ □ □ □ ● ◘ ◘ ◘ □ ◘ ● ● □ ◘ ◘ □ ◘ ● Notification of award ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ◘ ● ● ● ● ◘ ◘ ● □ ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ◘ ● 9 10 5 18 4 17 4 14 12 Public procurement: Main challenges identified by potential bidders Low knowledge/ ICT skills Australia Austria Belgium Canada Chile Denmark Estonia Finland France Germany Greece Hungary Ireland Italy Japan Korea Luxembourg Mexico Netherlands New Zealand Norway Poland Portugal Slovak Republic Slovenia Spain Sweden Switzerland Turkey United Kingdom United States OECD 31 Low knowledge of the economic opportunities raised by this tool Difficulties to understand or apply the procedure Difficulties in the use of functionalities (e.g. catalogue management) Low propensity to innovation Do not know No major challenges faced by potential bidders/suppliers ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● ● 14 12 ● 13 ● ● 13 ● 10 7 Financing democracy: Increasing transparency and accountability • Disclosure requirement as a tool for accountability and transparency in the decision making process Financing democracy: connecting the dots for scrutiny remains difficult • Identifying individual donors is necessary to track their record of doing business with the state OECD Integrity Review: what benefits? • Evidence based findings and tailored recommendations • Inclusive processes build consensus and ownership • help policy makers with options for improving policies, adopt good practices and implement established principles and standards • OECD Integrity Review of Brazil and Italy Thank you for your attention For more information on OECD experience on managing conflict of interest www.oecd.org/gov/ethics

© Copyright 2026