Soleado - Dual Language Education of New Mexico

A Publication of Dual Language Education of New Mexico Fall 2015 Soleado Promising Practices from the Field Sheltered Instruction: Affirming our Students’ Cultural, Linguistic, and Personal Identity by Ruth Kriteman—Dual Language Education of New Mexico students in developing a positive identity as As caring and committed educators, we like to believe that our efforts within the school’s walls— an active, capable, and developing bilingual and biliterate member of a community focused on what happens within our classrooms of learners. One way to accomplish this as well as the environment we create within the affirmation is Bridging the Two Languages, school community—can reverse some of the the last of DLeNM’s negative effects of components of our nation’s social sheltered instruction. and political realities This refers to the on students. This intentional and sociopolitical context careful development includes laws, of metalinguistic policies, practices, awareness—an and traditions awareness of the that impact every nature of language and decision made about how language forms education (Nieto, can be manipulated 2011). The truth is A culture of caring, respect, and high expectations that educators can do promotes student engagement and achievement. and changed to convey meaning. little to change the Strategies developed in one language can impact of student socioeconomic levels, levels then be bridged to another. In this way, we, of parent education and involvement, societal as teachers, identify the linguistic assets discrimination and stereotyping, difficult living students bring to a learning task and help circumstances, and racial or ethnic stratification. What we can control is the them develop those same strategies and context of school—our strengths in the second language. Inside this issue... collaborative work to set standards and goals, the ways Students need to feel that they are accepted Using Goal Setting to Impact we communicate belief in and valued by others. How can we ensure Kindergartners’ Achievement students’ capacity to achieve, that these needs are addressed? One essential Aprendiendo a aprender: El the school culture we establish, way is to recognize who these students are. uso de cuadernos interactivas and the support systems we They are not two monolinguals in one body. ... en la escuela secundaria enact that value and promote They have a bilingual identity that is unique academic achievement. and important and deserves to be affirmed. Academic Conversations: How Research on the complex conditions that the VISITAS Process Helped The importance of this kind of affect school achievement has identified the Develop a Schoolwide Focus ... affirmation—the affirmation need for an “ethic of care”(Noddings, in Nieto, Afirmando la identidad de of students’ cultural, linguistic, 2011). This ethic of care goes far beyond nuestros estudiantes y and personal identity—is simply adopting a caring attitude toward acelerando el aprendizaje ... the topic of this installment students. It involves showing students care by developing a close and affirming relationship Reauthorizing the Elementary and in our ongoing series on sheltered instruction. We call with them, adopting high expectations for Secondary Education Act this component Affirming their capabilities, and showing respect for Identity. It involves supporting their families. —continued on page 10— ; ; ; ; ; Using Goal Setting to Positively Impact Soleado—Fall 2015 Promising practices... Kindergartners’ Achievement by Lisa Ulibarri–Miller—Eubank Academy of Fine Arts, Albuquerque Public Schools Last summer, I was sitting in an AIM4S3™ training looking ahead to my second year of teaching kindergarten and wondering how I was possibly going to use a PDSA (Plan Do Study Act) cycle with my students. I find it challenging to use data in order to drive my instruction, yet I was presented with the idea of students using data to drive their achievement. What in the world does this look like in kindergarten? In part, this question drove my instruction this past year. use in Math and English language arts (ELA). Step one was to ask students what our goal should be for today’s lesson. Step two—as soon as those words were spoken I realized that my young scholars had no idea what I was talking about. Step three was to take a step back and rethink: What do my students need to understand in order to engage in goal setting? They need to know what a goal represents and why it is important to them. And so I began contemplating a different entry point. I decided to first approach Plan, Do, Study, Act. goal setting with students What does this mean individually. We created a to a 5-year-old? Not personal PDSA document much. Yet at its core, for each student in both ELA this idea of creating a and Math. I conferenced with plan, determining what each student and asked them steps must be taken what they wanted to learn to realize the plan, and how they thought they analyzing progress, and could learn it. Nearly every student said they needed planning next steps is the their parents’ help and for me very process that helps to teach them. Next, I asked everyone to accomplish what they were going to do tasks successfully. In Ms. Ulibarri–Miller and a student collaborate to achieve their goal. This simple terms, PDSA is on an individual PDSA. was a challenge! Ultimately, goal setting. Goal setting most responses were things like practice counting, is accessible to 5-year-olds. I just had to determine recite the alphabet on the playground, and ask for help. an entry point to begin teaching my young scholars what goal setting means, what it looks like, and how Then, I asked students how we would know when they reached their goals. Some suggested that I ask them or why it is meaningful. to count or identify letters and sounds, and a few said they would let me know when they were ready. I was once again stumped, until I attended an 3 AIM4S ™ classroom demonstration. Lisa Meyer, of DLeNM, was guiding second-grade students through Just before parent/teacher conferences, we reviewed a lesson on place value when she did something very their goals and made adjustments. When I met with their parents, I went over the student goals and asked curious. There were some spritely behaviors, so she parents how they were going to support their child and set up a class PDSA chart that addressed the three standards she expected students to adhere to during me in achieving these goals. The experience was eye– opening as I witnessed how many parents had never the lesson: show respect, make good decisions, and considered their contributions to the academic success solve problems. When the lesson concluded, she of their children in this way. Student goals were revised reviewed the PDSA chart and asked students to throughout the year with proficiency to the standards reflect upon how they met the standards. Bingo! being the benchmark. Some students fell shy of the Using concrete classroom behavior expectations to begin teaching goal setting would be my entry point. benchmarks while others surpassed the standards. For my students who owned their goals, achievement increased on a steeper curve than for students who did Excited about my idea, I jumped straight into the not seem to value their goals. fire. I got to school and created two PDSA charts to —continued on page 3— 2 DLeNM Through student conferencing, it became crystal clear that goal setting needed to be intentionally taught to students. At this point, each student had a personal experience with goal setting and a foundation to build upon and facilitate goal setting in the classroom. Going back to my initial attempt at using a class-built PDSA, my first step changed drastically. Rather than ask my students for a goal, I began by explaining our task for the day and why it was important. At that time, we were trying to establish independent literacy rotations. The students were taking too much time to transition between stations, and I was spending too much time reminding them of the behavior I expected while they were working. The students were frustrated they did not get to visit all of the stations, and I was frustrated I was not getting to work with all of the groups. In order to increase our success, we set up a class PDSA chart. Our goal was to complete three 10-minute rotations before our pullout. Our plan was divided between teacher and student. The students wanted me to just “teach them.” I agreed to this, but also suggested that if I set the timer, transitioned with our word of the day, and played soft music these strategies should help us be successful. The students agreed to “be good” and “not hit or kick our friends.” I suggested if they spoke quietly and stayed focused on their task we would be more successful. We decided that if we completed three rotations, we would meet our goal. In Math, our class PDSAs were more data specific. Counting to 100 was part of our daily routine early in the year. I expected that by January most of my students would have mastered counting to 100. The question is not new and interest has been renewed in recent years. In 1997, Albert Bandura described a critical component of goal setting as self-efficacy. Bandura (1997) describes selfefficacy as a “belief in one’s personal capabilities” (p. 4). Simply believing in one’s self is not enough in and of itself to be successful. Hallenbeck and Fleming (2011) assert that “goal setting is not an innate skill” (p. 38) and that achievement of goals is based upon learning how to set achievable milestones and planning a route to reach them (p. 38). A study by Arslan (2012) reports that students stated their self-efficacy beliefs increased with successful performance accomplishments in the academic environment (p. 1918). Setting goals and then analyzing data which indicates goal achievement provides students a venue in which they can own their learning. Moreover, goals become something tangible and concrete even though the goal itself may be abstract. Arslan, A. (2012, Summer). Predictive power of the sources of primary school students’ self-efficacy beliefs on their self-efficacy beliefs for learning and performance. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 12(3), 1915-1920. Bandura, A. (1997). Insights. Self-efficacy. Harvard Mental Health Letter, 9(13), 4-6. Hallenbeck, A., & Fleming, D. (2011, Spring). Implementing a goal-setting intervention in an afterschool program. Afterschool Matters, 13, 38-48. Assessment data spoke otherwise. In an inclusion class of 27, seven students were counting to 100 and one was stuck somewhere between 70 and 80. The vast majority of my students were stuck at 29 or 39. Consequently, we created a class PDSA with the goal being counting to 100 or 120. Then, each student present that day placed a dot with the number they counted to on a black rectangle (0–49), blue rectangle (50–99), or red rectangle (100+). As we analyzed the dots, students immediately gasped as they realized most of the dots were on black. I was honestly surprised that, without saying a word, my students fully understood the message—we’re behind. Soleado—Fall 2015 On our first attempt, we completed one rotation. When we debriefed and created our action plan we agreed that “Mrs. Miller forgot to set the timer,” and we started rotations late. We kept the same PDSA for a week, and by Friday, rotations were going smoothly. By using the PDSA in this manner, my students learned strategies they needed in order to be independent. As the year went on, they were increasingly specific regarding what they would do. Their requests to me included: “don’t forget to set the timer,” “play guitar music,” “spread us out more,” and “make sure we made smart choices where we are sitting.” Additionally, they agreed to “be a professional and do my best,” “talk quietly,” “stay focused,” “ask my friend,” and “help my friend learn.” My students learned to identify the strategies that helped them become successful, independent learners. Why does it make sense to teach kindergarten students about goal setting? Promising practices... —continued from page 2— —continued on page 12— DLeNM 3 Soleado—Fall 2015 Promising practices... Aprendiendo a aprender: El uso de cuadernos interactivos en dos idiomas como estrategia para promover un aprendizaje significativo en la escuela secundaria 4 por Mirle Hernández—Escuela Secundaria Truman, Escuelas Públicas de Albuquerque “Cuando tomo un examen, es fácil recordar el contenido de mis cuadernos porque he tomado mis propios apuntes y he dibujado tanto, que tengo mis cuadernos grabados en la memoria”, comenta Eva Trevizo. “Y hemos aprendido lo que podemos hacer para memorizar y aprender información usando nuestras propias estrategias”, agrega Natalia Delgado. Eva y Natalia son estudiantes, que en mayo del año 2015 terminaron tres años de educación en el programa de lenguaje dual de la Escuela Secundaria Truman, en Albuquerque. Cada equipo académico tiene un nombre; el equipo de sexto grado se llama Los Ocelotes; el de séptimo grado, Los Linces, y el de octavo grado, Los Leones. Este diseño permite que cada grupo de maestros se reúna dos o más veces por semana a conversar acerca de sus estudiantes y a planificar el currículo incorporando las estrategias necesarias para proveer apoyo decreciente a los estudiantes aprendientes de inglés y a los estudiantes aprendientes de español. El uso de los cuadernos interactivos en la Escuela Secundaria Truman se inició a partir del entrenamiento de verano en el año 2012 para AVID, un programa dedicado a cerrar la brecha de logros, preparando a cada estudiante para la educación superior, que se enfoca en el progreso a través de la determinación individual. El cuaderno interactivo es una herramienta de aprendizaje diseñada para fomentar la creatividad, la organización sistemática y la creación de un portafolio personal del proceso de aprendizaje de cada estudiante. Este cuaderno elimina la desorganización y confusión que enfrentan los Natali Barreto-Baca, maestra estudiantes en su transición de de ciencias en el equipo de los la escuela primaria a la escuela Linces, comenta que hace más de Un Ocelote crea plegados para secundaria. En lugar de hojas tres años, decidió participar en el aprender vocabulario nuevo. sueltas, copias y folletos, cada entrenamiento y formar parte del estudiante crea un libro personal de estudios, con grupo AVID de la Escuela Secundaria Truman. sus propias ilustraciones, reflexiones y comentarios. Los estudiantes que participan en el programa de La calidad y el contenido de los cuadernos creados lenguaje dual en nuestra escuela usan cuadernos por los estudiantes de Natali Barreto-Baca, el orgullo interactivos en todas sus clases. y elocuencia con la cual estos estudiante describían su trabajo en estos cuadernos y lo que significaban en su El programa de lenguaje dual de la Escuela aprendizaje, en combinación con el entrenamiento de Secundaria Truman está diseñado como una un mayor grupo de maestros en el uso de estrategias miniescuela de 345 estudiantes, dentro de una comunes, como los apuntes Cornell, animó a que los escuela de casi 1400 estudiantes. En cada uno de los tres equipos del programa de lenguaje dual adoptaran tres grados—sexto, séptimo y octavo—del programa, el uso de los cuadernos interactivos para todos sus hay un equipo de cuatro maestros que enseñan las estudiantes durante el año escolar 2014-2015. materias básicas requeridas, dos de estas materias se dictan 100% en español y dos materias 100% en El formato tradicional de un cuaderno interactivo inglés. Cada equipo de maestros tiene un periodo de (TCI, Teacher’s Curriculum Institute) se basa en preparación común y enseña al mismo grupo de 115 estudios de la neurociencia acerca de la retención, la estudiantes quienes tienen una diversidad de niveles memoria y la función específica de cada hemisferio de competencia lingüística en español y en inglés. —continúa en la página 5— DLeNM Promising practices... —continuación de la página 4— cerebral. Algunos maestros usaron este formato y otros maestros experimentaron con sus propios formatos. A finales del primer año de experiencia usando los cuadernos interactivos, cada equipo ha discutido algunos cambios para el año escolar 20152016. Este ha sido un año de aprendizaje tanto para los estudiantes como para los maestros. Los Ocelotes En el equipo de 6to grado, la maestra de ciencias naturales, Cilian Pérez , y la maestra de humanidades, Barbara Sena, enseñan en español. Cilian Pérez, entrenada en AVID, usa el formato TCI del cuaderno interactivo y Barbara ha adaptado el formato del cuaderno a su estilo de enseñanza. Explica: Les he enseñado a mis estudiantes a tomar apuntes útiles para responder a preguntas, un paso difícil para estudiantes de sexto grado. Para mí, fue más práctico usar carpetas de tres aros para que mis estudiantes crearan sus cuadernos porque así fue más fácil agregar páginas e información, pero el año que viene quiero usar el formato tradicional, con la sección del estudiante a la izquierda y la sección de la maestra a la derecha. La maestra de lenguaje e inglés como segunda lengua, Theresa Durán, también ha usado la carpeta como portafolio personal pero ha agregado estrategias de AVID, como el uso de los apuntes Cornell, que fueron el enfoque del desarrollo profesional de los maestros de Truman durante el año escolar 2014-2015. Las ilustraciones personales apoyan el aprendizaje de nuevos conceptos y vocabulario académico. y octavo grado vean lo que aprendimos, apoyando así la continuidad vertical del aprendizaje en nuestro programa de lenguaje dual. Michael Pedersen, maestro de matemáticas en inglés, comenta: Mis estudiantes tienen el currículo de ciencias al principio del cuaderno y una tabla de contenidos. Uso rúbricas para evaluar los cuadernos. Nuestros estudiantes saben leer y escribir pero no tienen buenas estrategias para recordar. Yo les enseño a usar los apuntes Cornell y a practicar la asociación entre un concepto y una ilustración como técnica de memorización. Los estudiantes aprenden vocabulario académico científico creando sus propias ilustraciones. Soleado—Fall 2015 Para mí fue muy positivo ver cómo mis estudiantes usaban sus cuadernos interactivos como recurso para repasar los conceptos aprendidos en la escuela. Los estudiantes usaban sus cuadernos para estudiar en casa. Esto les sirvió también para explicar a sus padres y familiares lo que estaban aprendiendo. El próximo año quiero incluir mucho más; secciones para las normas comunes, preguntas esenciales, objetivos, vocabulario, apuntes y ejemplos de problemas. Me gustaría que los estudiantes conserven sus cuadernos de sexto grado como recurso en séptimo y octavo grados y hasta en la preparatoria. De esta manera, el cuaderno servirá para que los maestros de séptimo Los Linces Los cuatro maestros de séptimo grado, Natali Barreto, Linda Varela, Desiree Nuanes y Angel Méndez asignaron cuadernos y cada estudiante tenía la responsabilidad de llevar sus cuatro cuadernos o su carpeta de AVID, de la escuela a la casa y de la casa a la escuela. Natali Barreto-Baca, maestra de ciencias en español y veterana en el uso de los cuadernos interactivos, explica: —continúa en la página 14— DLeNM 5 Encouraging Academic Conversations: Soleado—Fall 2015 Promising practices... How the VISITAS Process Helped Develop a Schoolwide Focus on Learning and Interaction 6 by Terese Rand Bridges, Instructional Coach—Coronado Elementary, Albuquerque Public Schools by having teachers ask themselves, “What makes Coronado Elementary School, in Albuquerque, is the teaching, learning, and content effective in this a dual language school that implements a 90/10 setting?” The observations also address the dual dual language program in Spanish and English. language setting by including scaffolds for language Coronado’s student population is 88% Hispanic, and the majority of these students are from English- development such as planning for peer interaction, activating prior knowledge/building on shared speaking homes. Given these demographics, our school can be considered to have a heritage language knowledge, and affirming identity. Edward TabetCubero, former associate program that is open director of DLeNM, to all children in the introduced us to the Albuquerque area. idea of VISITAS when Coronado Elementary In the current climate of became a part of the Bright the Common Core State Spots Initiative early in Standards (CCSS) and 2014. DLeNM’s Bright closely related testing Spots Initiative is funded demands, all schools by the Kellogg Foundation face challenges. Dual and is intended to support language schools have the the development of additional challenge of exemplary dual language teaching the demanding programs across the state. content of the CCSS in two languages. But for Teachers participate in a classroom observation The VISITAS approach Coronado Elementary, based on identified “look fors” during VISITAS. worked well for Coronado like many programs, our biggest challenge as a dual language school is getting Elementary because we have a high level of respect students to talk about what they are learning in their between our teachers, but we didn’t always have a clear understanding of our common goals or how we second language, which for us is usually Spanish. could best improve instruction in a cohesive way. As Spanish language production for non-native City et al. (2009) state, “One of the greatest barriers speaking children is difficult, particularly when to school improvement is the lack of an agreed-upon the academic content itself is challenging. We have definition of what high-quality instruction looks addressed this head-on by developing a schoolwide focus on student-to-student academic conversations. like” (p. 3). Even more critically, teachers had to believe that VISITAS would not be one more thing required of them, but a process by which we could We developed this schoolwide focus collaboratively improve together. Teachers had wanted to visit each by participating in a set of classroom observations other’s classes and had even included this as a goal in called VISITAS, facilitated by Dual Language their yearly improvement plans. But often, teachers Education of New Mexico (DLeNM). VISITAS are more eager to observe someone else than to stands for Viewing Interactive Sheltered Instruction, be observed, and this was the case for Coronado. Teachers and Students. VISITAS is DLeNM’s Putting the VISITAS process in place helped us face variation of the instructional rounds model, which this reluctance to have our peers come observe our provides teachers with the opportunity to see classrooms and our instructional practice. From the what’s happening in other teachers’ classrooms beginning, the norms that are central to VISITAS by using close observation that is descriptive and helped us to be more comfortable with the visitation non–judgmental (City, Elmore, Fiarman, & Teitel, process (see sidebar, p. 7). 2009). VISITAS observations move from “problems of practice” to taking an assets-based approach —continued on page 7— DLeNM We also eased our way in to the VISITAS process by first visiting classrooms when students were not present. In April 2014, a small team of teachers, DLeNM staff, and Coronado administrators conducted walkthroughs of several different classrooms during noninstructional time. Edward Tabet-Cubero helped us design the “look-for” protocol that we used to observe classroom arrangement, communication of standards, charts, and evidence of language development. For the 2014–2015 school year, we planned monthly VISITAS dates in advance and lined up substitutes so that teachers could visit each other’s classrooms and participate in the discussions and reflections. For these VISITAS, we observed classroom instruction. We began each day by going over the norms, which included presuming positive intentions and maintaining confidentiality in the data that we gathered. We made it clear that we were not looking for practices that were missing in our classrooms, but instead looking in an intentional way at what students were doing and evidence of the “look fors” so we could build on the potential that was already there. After the briefing, a group of five to eight teachers and administrators visited the first classroom for about 15 minutes. During the visit, we took notes on the “lookfor” protocols, which helped focus our attention on the practices we wanted to observe. Importantly, VISITAS enabled us to come to a common vision of how we wanted to improve as a school. In September, the practices we decided to look for were broad and not well focused. The “look-for” protocol listed locus of control, bridging between languages, and academic dialogue as areas to observe. In our observations and follow-up discussions, it quickly became apparent that all classrooms were working on getting students more involved in speaking v Focus on student learning v Look for what’s there, not what’s lacking (asset approach) v Encourage and celebrate risk taking v Keep the data collection anonymous v Presume positive intent v Maintain confidentiality Spanish, so in October we narrowed our focus to questioning strategies and academic conversations. After the October round of observations, we knew that we wanted to concentrate on academic conversations—student output—and we started a book group to read and discuss Academic Conversations: Classroom Talk That Fosters Critical Thinking and Content Understandings (Zwiers & Crawford, 2011). We also invited Diana Pinkston– Stewart from DLeNM to provide professional development on the topic in November. When we resumed our VISITAS in January, all of the “look fors” in our observation protocol had to do with academic conversations. What opportunities did the students have to engage in conversations with each other? What student behaviors were evident during those interactions? What scaffolds supported these conversations? As we considered how to go deeper with these conversations, we decided to visit only three classrooms for a longer period of time (45 minutes) in February. These modified “lesson study” visits were designed to model how to engage students in more reflective thinking, such as identifying mathematics strategies and giving reasons to support their opinions in an argument. In April, we concluded our observations by reviewing Zwiers and Crawford’s five skills that focus and deepen academic conversations (2011), and each grade level worked on planning a lesson or unit in language arts or math that included academic conversations. DLeNM Soleado—Fall 2015 After the first classroom visit, we had a brief checkin to make sure we were looking for the same things. Then we visited four more classrooms. After the visits, we took some time to go over our observations individually and to start grouping them into positive statements of what was observed. An example would be, “In four of the five classrooms we visited today, I observed students using sentence frames to scaffold their responses.” We called this the “data dump,” and by making these general statements about what we observed, we maintained individuals’ confidentiality while being able to give feedback to them the same day. Key to ensuring that the VISITAS process is “safe” for teachers and non-evaluative in nature, the following norms are always adhered to: Promising practices... —continued from page 6— —continued on page 15— 7 La enseñanza contextualizada (Sheltered Instruction): Promising practices... Afirmando la identidad de nuestros estudiantes y acelerando el aprendizaje por medio de ambos idiomas Un diálogo de Soleado en curso por Adrian Sandoval—Dual Language Education of New Mexico Una verdad innegable en cuanto a nuestros estudiantes es que la mayoría de ellos pertenecen a una comunidad que se encuentra fuera del poder. A veces esta es una realidad que nuestros estudiantes y sus familias enfrentan por la primera vez y en otros caso es ya un legado de generaciones. En ambos instantes el resultado común es un grupo de personas que se siente marginado a la energía y potencia positiva de la sociedad. Bajo el peso de tal legado, cada individuo lleva dentro de sí, consciente o inconscientemente, un bagaje emocional con diversas características como la falta de autoestima, la vergüenza por la apariencia física y/o el idioma que se habla en el hogar, la pobreza y sus múltiples faces, y la falta general de comodidad en las situaciones dominadas por el grupo “en poder”. Soleado—Fall 2015 Todo lo susodicho corresponde a la parte invisible del iceberg que sirve como metáfora para la realidad que viven muchos de nuestros estudiantes y sus familias de una manera tácita. 8 Junto con este iceberg agregaremos otro aspecto innegable. Es decir, la secundaria y preparatoria siempre han sido el campo donde, por cuestiones de la adolescencia, nuestros estudiantes están buscando su lugar en el mundo y luchando con las nociones de pertenecer a algo y encontrar quienes son. Desafortunadamente, también es el momento cuando la expectativa del salón de clase es de silencio y, por cuestiones del número de estudiantes en el salón, un lugar donde muy pocas veces cada estudiante sea reconocido como un ser cuyo pensamiento y voz tengan valor. Es más, muchos estudiantes a este nivel ya se sienten como seres invisibles y han adoptado y desarrollado a este papel desde la primaria por culpa del dicho “iceberg”. Como maestros, estas tres realidades nos recuerdan el por qué tenemos que afirmar la identidad de nuestros estudiantes como parte integral de su experiencia en el salón de clase. ¿Pero cómo y dónde lo hacemos? El proceso comienza con la planificación de clase, y reflexionando sobre quiénes son los seres en nuestro salón. ¿Qué sabemos de ellos? ¿Qué sabemos de sus familias, su historia, y su cultura en general? Después, sigue el proceso de planificación con el esfuerzo deliberado de activar conocimientos previos, y crear un ambiente donde valoramos y promovemos a nuestros estudiantes como fuentes de conocimiento de alto mérito. Algunas estrategias sencillas que he usado para lograr afirmar las identidades de mis estudiantes son lo siguiente: = crear oportunidades para que los jóvenes comparten lo que saben del tema y lo que quisieran saber por medio de una gráfica, = hacer que los estudiantes hagan una entrevista con algún familiar para investigar y valorizar lo que se sabe acerca del tema estudiado, = invitar al salón claros representantes de la cultura de nuestros estudiantes que pueden agregar más información en cuanto al tema, y = utilizar libros de ficción y no ficción que son lingüísticamente auténticos y atados a la cultura juvenil y étnica de nuestros jóvenes. Cuando de verdad mostramos un interés genuino en cada uno de nuestros estudiantes interrumpimos al ciclo de invisibilidad que ha permanecido en sus vidas por un periodo de tiempo demasiado prolongado. En muchos casos, es la primera vez que estos jóvenes se sienten visibles y vivos dentro del ambiente escolar. El crear una rutina de pedir ideas de cada individuo, valorar sus ideas, e intentar comprender estas ideas en el contexto de su cultura y su realidad actual es el primer paso hacia afirmar la identidad de nuestros estudiantes. En un artículo de Teaching Tolerance titulado «What Can This Student Teach You About the Classroom? » (Number 36, Fall 2009), igual dice Tranette Myrthil, estudiante e hija de inmigrantes haitianos, hablando de una clase que marcó una diferencia en su vida: DLeNM Hubo debate en clase y escuchábamos el uno al otro. Esa fue una clase donde verdaderamente importaban qué aprendíamos, cómo aprendíamos, —continúa en la página 9— Promising practices... —continuación de la página 8— y si entendíamos o no. Les importaba cómo nos sentíamos en cuanto a una situación. Aprendí que tenía una voz. Estrategias que usaba para lograr semejante éxito en mi clase se basaba en lo siguiente: = primero seleccionar un tema de alto interés, = crear un conocimiento mutuo del tema que toma en cuenta la cultura y los niveles lingüísticos de los estudiantes, = modelar para los estudiantes las expectativas de su interacción en parejas, grupos, y/o con la clase entera, = ofrecer y modelar una opción de gráficas que les puede ayudar a los estudiantes desarrollar y organizar sus ideas, En un ambiente afirmativo, los alumnos participan activamente en el aprendizaje. = crear y compartir con los jóvenes un esquema de valores para que sepan como los vamos a calificar, y = apoyarles con claras frases que modelan cómo mejor iniciar sus respuestas. Aparte de la obligación como maestro de afirmar la identidad de nuestro alumnado, tenemos que también reconocer las oportunidades que se ofrecen en el salón para apoyarles como bilingües emergentes con esfuerzos precisos e intencionales. El apoyo que sugerimos no sólo podrá impactar positivamente a la identidad lingüística del estudiante sino también al crecimiento académico. Este apoyo que sugerimos tiene que ver con la importancia de explícitamente iluminar las semejanzas y diferencias entre ambos idiomas que desarrollan nuestros estudiantes. Como última muestra personal de esta oportunidad que nos exige la relación entre estudiante y maestro al nivel metalingüística, llevo como recuerdo lo que me enseñaron en un curso universitario llamado Fonética y fonología. Allí aprendí que tenemos en español lo que se llama la d oclusiva y la d fricativa. Resulta que la oclusiva es como la d del inglés, y la fricativa tiene como paralelo a la th del inglés. Cuando mostré a mis estudiantes que existía la pronunciación de th en español, llamada la d intervocálica, dimos énfasis en la posición de la lengua inmediatamente detrás de los dientes y así usamos un lenguaje para ayudar al otro. Como dice en latín—manus manum lavat—pero en este caso se trataba a las lenguas y no las manos. Afirmar la identidad de los jóvenes que entran a nuestros salones es lo más mínimo, básico, y profundo que podemos extender hacia nuestro DLeNM Soleado—Fall 2015 ¿Cuántas veces hemos compartido una palabra o frase que bien sabemos tiene una traducción distinta en ambos idiomas y que puede resultar ser problemática, o como parte de nuestra instrucción usamos unos cognados sin tomar el tiempo de revelarlos así? Con referencia al metalenguaje (lenguaje que se usa para hablar de aspectos propios de una lengua, y en el caso del bilingüismo, también de las similitudes y diferencias que existen entre los dos), la Dra. Kathy Escamilla (2013) sugiere que podemos compartir con el estudiante unas frases en ambos el español e inglés para mostrarles que siguen la misma regla de comenzar con una mayúscula. Mientras tanto, los días de la semana sólo llevan mayúscula en inglés. Otro ejemplo en la penúltima frase sería el uso formal de la palabra similitud en vez de “similaridad” que más bien es una sobregeneralización departe de un hablante nativo de inglés acostumbrado a utilizar cognados directos de inglés a español para elevar el vocabulario a un nivel más académico. Un esfuerzo para lograr esto sería una inversión en el proactivismo con el cuál evitamos corregir y menospreciar al conocimiento y las estrategias que traen nuestros estudiantes al salón. Estaríamos directamente conectándoles a ciertos detalles importantes de sus idiomas para que ambos vayan desarrollándose aún más rápido y con más precisión. —continúa en la página 12— 9 Promising practices... —continued from page 1— Many of the stories we hear of students living in difficult socioeconomic, sociocultural circumstances who find success in rigorous school programs despite great obstacles all have one thing in common. Their instructional staff, their principal and teachers, believe their students can learn. The staff recognizes that success may hinge on putting into place intentional, structured scaffolds, but, with that support in place, the students can achieve. We need not be afraid of rigorous content, of Common Core or Next Generation standards. Our students are smart, capable, creative beings who can achieve what is expected of them. As teachers, we need to communicate that belief: I believe in you. You are going to be successful someday. You’re going to make it! One popular quote on social media reflects this point in the voice of a 6 year old: My teacher thought I was smarter than I was, so I was. Soleado—Fall 2015 We need not be afraid to help students look at their own data folders to both celebrate great progress and to develop a plan to address learning gaps. Students deserve to know where they are successful and where they aren’t, especially when they are given a role in developing a plan to improve. How empowering is that? What student wouldn’t rise to that challenge? 10 Affirming the families and cultural traditions of every student must go beyond a cursory celebration of cultural heroes and holidays. Far more effective would be assertively confronting stereotypes or other forms of racism and bias. I remember being called into a meeting attended by members of a middle school’s administrative team, a counselor, classroom teachers, and a student and her mother. The meeting began with a stern lecture regarding the importance of regular attendance, the need to remain in the country in order to ensure better English proficiency, and the current “unacceptable” practice of heading down to Juárez every Friday after school. It wasn’t until I asked the student and her mother why they were going to Mexico every week that we learned that the family’s grandmother was terminally ill and they were spending as much time with her as possible. How could it be that these educators never bothered to ask the student about her reality? How could it be that the school’s first response was to convene a meeting of an intimidating number of educators to lecture the family on attendance? The school’s response was predicated on the belief, acknowledged or not, that this family didn’t value school, didn’t acknowledge the incredible gift this student had available to her in the form of a free public education, didn’t take seriously the need to use her English. That was not it at all—instead, what took precedence was the familial relationship and the need to honor and acknowledge an elder’s place in the family. Strategies to Support a Sense of Community Examining attitudes in the larger school community is one important step in affirming identity. There are also classroom strategies that can make a difference for students. The T-graph for Social Skills is a Project GLAD® strategy in which a social skill is identified and shared with students. Students each take their individual notions of appropriate and productive behavior in a group and negotiate a common understanding and set of expectations for that behavior. The idea is to support students in identifying and developing behaviors consistent with a positive classroom environment. The social skill becomes the focus for a period of 4 to 6 weeks. For example, students focusing on Collaboration might identify working together, sharing the work, and helping each other. Under a semantic web of these initial thoughts, the teacher creates a T-graph. The left side is labeled with a sketch of an eye while the teacher asks what collaboration would look like if one were to pass by the classroom and look inside. What would that person see? Students are working together to finish a project, kids are sharing their materials, kids’ eyes are on the person talking. On the right side of the chart the teacher sketches an ear and asks the students what collaboration would sound like. What might someone hear that could be recognized as showing collaboration? Again, students generate positive behaviors: polite language like “please” and “thank you;” appropriate ways to disagree, such as “that’s a great idea but have you thought of ... ;” or quiet voices of students taking turns. These lists of behaviors that can be seen and heard then serve as behavior management. The fact that this chart is created with students collaborating and contributing their ideas and expectations affirms their identity and place in the classroom. The power of this strategy lies in the fact that the students are given agency and voice in developing the class definition of the social skill. More information on this protocol is available via Project GLAD® training. DLeNM —continued on page 11— Many teachers rely on regular class meetings that follow a particular protocol to model and support a positive classroom in which every student has a voice. Some teachers begin the class meeting with a quick whip-around of positive behaviors: I liked it when Ben shared his pencil when mine broke. Then, concerns and problems are discussed using a talking stick or some other method to ensure equity of voice and participation. literacy. These skills include the ability to express oneself, to understand speech, and to bridge two languages. One highly effective strategy is called Así se dice; it provides students with an opportunity to negotiate meaning and experience the flexibility and subtleties of translation. In this strategy, the teacher selects a short passage, a poem, or an idiomatic expression in one language and gives it to pairs of students to translate into the other language. Promising practices... —continued from page 10— I experienced this strategy with a short selection from Sandra One highly effective way of Cisneros, Pelitos, that is written acknowledging students’ in Spanish and describes the prior knowledge and hair of each of her family experience is recognizing members, with special emphasis and building on the on her mother’s hair. The linguistic resources students language is rich and evocative. Así se dice bring to school. In many Translating it with my partner cases, that linguistic resource is a different language. involved lengthy discussions about how to use In other cases it may be a different dialect or way of English to express the same description and evoke using language to express oneself. One example of the same emotions. When each pair shared out, we this is the story-telling tradition of many cultures. had even more opportunities to discuss word choice Teaching and learning opportunities might take the and other subtleties. It was great fun and it allowed form of a story that illustrates the key lessons. A us to use our skills as bilinguals. In other words, literature selection may be previewed in story-telling it acknowledged the very specific skills that we format using pictures, puppets, or live action so brought to the task and gave us an opportunity to students have a sense of the story line and vocabulary flex and extend those skills and clarify how to best before they ever see the piece in written form. use our language to convey meaning. Strategies to Bridge Students’ Languages Dr. Kathy Escamilla and her colleagues, in their book Biliteracy From the Start, describe several strategies designed to develop students’ oracy, or the oral skills that contribute to the acquisition of Escamilla, K., Hopewell, S., Butvilofsky, S., Sparrow, W., Soltero-González, L., Ruiz-Figueroa, O., & Escamilla, M. (2014). Biliteracy From the Start. Philadelphia, PA: Caslon. Beeman, K., & Urow, C. (2013). Teaching for Biliteracy—Strengthening Bridges Between Languages. Philadelphia, PA: Caslon. Soleado—Fall 2015 Karen Beeman and Cheryl Urow, in their book Teaching for Biliteracy—Strengthening Bridges Between Languages (2013), share many strategies that strengthen the bridges between languages in bilingual or dual language settings. One simple strategy uses Total Physical Response as a bridge. Vocabulary for a lesson in one language is reinforced with the use of gestures to illustrate the meaning of the words. When the language of instruction changes and lessons are extended (not repeated) in the new language, those same gestures are used to bridge the meaning of key vocabulary and provide students with the skills to convey concepts and learning in the new language. Affirming identity, acknowledging who our students are, honoring their families and the traditions that give their lives purpose, teaching them new and important skills and expanding their knowledge base … politicians, policy makers and community members can say what they will—we teachers know how critical our roles are in our students’ lives, and we rock! Nieto, S., & Bode, P. (2011). Affirming Diversity: The Sociopolitical Context of Multicultural Education (6th ed). Boston, MA: Pearson. DLeNM 11 Promising practices... —continued from page 3— Reflecting upon my year, I learned a few things. First, giving primary students the power to recognize strategies that help them learn and be successful gives them a personal reason for engaging in learning. Second, parents need to be an intentional part of the learning cycle. Third, as students articulate and justify the strategies that help them learn, they develop rich oral language skills that spill into all content areas. Finally, using the PDSA process and having intentional discussions on the strategies that are helpful in the Class PDSA for “counting to 100” Two weeks later, the data learning process seems to was significantly different. Only 10 students had place students on a steeper trajectory toward academic not reached proficiency and six of those were really success, which is critical for students’ achievement and close. I shared my success with my grade–level efficacy as thinkers and learners. team, and they all did something similar with their For more information about Achievement Inspired students. The results were impressive as the grade Mathematics for Scaffolding Student Success (AIM4S3™), level reached proficiency in rote counting. please visit aim4scubed.dlenm.org. We had some partner discussions about what the teacher should do to help the students achieve proficiency. My students were very explicit. First, they wanted me to tell their parents to help them count at home. Next, they wanted me to listen to them count individually more frequently. Then they realized that when we count in class, they should actually be counting! They suggested practicing counting to each other and on the playground. —continuación de la página 9— Soleado—Fall 2015 futuro encarnado. También somos responsables para que nuestros estudiantes tengan la oportunidad de explorar y descubrir las semejanzas y diferencias entre los idiomas que navegan diariamente. En fin, tenemos que ser conscientes de las oportunidades que se revelan en el salón para así aprovechar del momento con apoyo lingüístico directo y asegurarles 12 que son vistos, tienen valor, y asegurarles que lo que traen al salón es útil y deseable. También, tenemos que planificar intencionalmente para que esto ocurra. No estamos sugiriendo que vayan traduciendo varias palabras y expresiones en su clase de inglés a español o vice versa. Tampoco estamos diciendo que el maestro sea singularmente dedicado al vínculo afectivo. Al contrario, sugerimos sólo que reconozcamos cuándo y cómo podemos usar aspectos de ambos idiomas como herramientas de claridad que aceleran al aprendizaje ya sea lingüístico, conceptual, o ambos a la vez. Es otra relación simbiótica que nos trae el regalo de aprender otros idiomas con mayor rapidez y precisión, y si lo alcanzamos hacer mientras valoramos a los chicos de la clase, hemos logrado ya mucho. DLeNM by James J. Lyons, Esq., Senior Policy Advisor—Dual Language Education of New Mexico In early September, when Congress reconvenes after its summer August recess, senior members of the House and Senate education committees will meet in a conference committee to thrash out differences in the bills passed in their respective chambers to reauthorize the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). Both H.R. 5, the Student Success Act (SSA), which passed the House of Representatives on July 8 and S. 1177, the Every Child Achieves Act (ECAA), which passed the Senate on July 16 are meant to extricate American schools from the policy quagmire of No Child Left Behind (NCLB) and the Obama Administration’s conditional ESEA “waivers.” The challenge of the conference committee is more than just reconciling differences in the House and Senate bills. The new bill crafted by the conference committee must then pass each chamber before it can be sent to the President, and, of course, must be signed by the President before it becomes law. Although the conference committee will be bipartisan, Republicans will comprise a majority of its members, as they do in both legislative bodies. Rather than providing a detailed analysis of the SSA and the ECAA, this brief article highlights some of the issues which are likely to be pivotal in the deliberations of the conference committee and subsequent legislative tasks. These issues have major implications for dual language education. The SSA caps or limits appropriations for the 5 years covered by the bill (FY 2016–2020) at FY 2015 levels with no increases to account for The SSA, but not the ECAA, calls for “portability” of Title I funds. If a student transfers to another school, regular or charter, the Title I funds would be transferred to the new school. Equity advocates view “portability” as the first step towards establishing a “voucher” program which could provide federal funding for private schools; they also object to “portability” as a mechanism that reduces funding for schools which are impacted by concentrations of poor students. Both the ECAA and the SSA maintain current requirements for annual standardized testing of English language arts, mathematics, and science as well as the public reporting of test scores disaggregated by the student subgroups specified in current (NCLB) law. Both ECAA and SSA, however, leave to the states complete authority to establish “accountability” systems including performance standards and determination of when and what schools require improvement actions. A number of civil rights organizations object to the elimination of federally-mandated accountability standards and school improvement requirements as a fatal flaw in the bills, and President Obama has hinted at a possible veto if the legislation does not continue current federal authority to compel change in local school programs. Watch for the next issue of Soleado, which will provide the latest—and hopefully good—news on the ESEA Reauthorization. James J. Lyons is a civil rights policy attorney in Arlington, VA. He can be reached by email at [email protected]. DLeNM Soleado—Fall 2015 The SSA effectively turns the ESEA into a “block grant” program merging existing separate programs for English learners (ELs), migrant students, and neglected and delinquent children into the larger Title I program for economically disadvantaged students. Local education agencies could spend Title I funds on any of the designated student populations. The ECAA continues the existing separate programs for different student populations. inflation or student population growth. Given the fact that ELs represent the fastest growing segment of our student population, this funding limitation would be particularly harmful. The ECAA eschews specific limits on appropriations, authorizing “such sums as may be necessary” for appropriations for FY 2016–2020. Promising practices... Reauthorizing the Elementary and Secondary Education Act: Differing Bills Approved by the House and Senate—Next Steps 13 —continuación de la página 5— Promising practices... Linda Varela, maestra de humanidades en español usa una carpeta de trabajo. Declara: Uso los apuntes Cornell frecuentemente y los plegados con ilustraciones para practicar nuevo vocabulario académico. A mi me sucedió algo interesante este año. Como mi clase es 100% en español, yo solo conozco el nivel de competencia lingüística de mis estudiantes en español, pero muchos de mis estudiantes participan en el programa AVID y ellos tienen todos los cuadernos de todas sus materias dentro de una sola carpeta. Esto me permitió ver también el nivel de competencia lingüística de mis estudiantes en inglés. La maestra de lenguaje e inglés como segunda lengua, Desiree Nuanes comenta: Puede ser difícil recoger 115 cuadernos para evaluarlos. Yo uso una estrategia para calificar el cuaderno: cada dos semanas doy un quiz acerca del contenido de los cuadernos. Cada estudiante usa una hoja suelta para tomar la prueba ¡Es SAVE THE DATE Soleado—Fall 2015 La Cosecha 2016 November 9 – 12, 2016 Santa Fe, New Mexico La Cosecha is hosted by Dual Language Education of New Mexico 1309 4th Street SW, Suite E * Albuquerque, NM 87102 www.dlenm.org 14 mucho más fácil llevar 115 hojas sueltas a la casa que 115 cuadernos! Estas son pruebas de 10 preguntas acerca de los apuntes y reflexiones escritas en los cuadernos cada dos semanas. Los Leones Nuestra expectativa es que cuando los estudiantes lleguen a su último año, octavo grado, en nuestro programa de lenguaje dual, sean expertos en la creación y organización de sus propios cuadernos. El maestro Sam Fretwell enseña lenguaje e inglés como segunda lengua, el maestro Scott Simpson enseña humanidades en inglés y español y los maestros Ruth Ramírez-Gurrola y Gilberto Lobo enseñan matemáticas, álgebra y ciencias naturales en español. En una reunión del equipo de Los Leones, los maestros comentaron que encontraron apoyo en una de variedad de páginas de recursos acerca de los cuadernos interactivos en Internet. Sam Fretwell comenta: Estos cuadernos ayudan a que los estudiantes adopten la idea de que ellos tienen el control de su crecimiento intelectual y que sus habilidades no son fijas, que todos pueden mejorar su manera de aprender. Además, el uso de cuadernos interactivos, en español e inglés nos permite analizar las estrategias que los estudiantes bilingües usan como aprendientes con un amplio repertorio lingüístico. Margie Milburn, maestra y coordinadora de AVID ha observado una diferencia entre los estudiantes del programa de lenguaje dual y sus compañeros que no participan en nuestro programa. Cuando los estudiantes bilingües trabajan en grupos de tutoría, el uso de sus apuntes en dos idiomas parece facilitar la comunicación y la comprensión del contenido. “¿Y qué harán en la preparatoria si los maestros no usan cuadernos interactivos?”, les pregunto a las estudiantes Eva Trevizo y Natalia Delgado quienes iniciarán su primer año de preparatoria en el otoño del año 2015. “Creo que seguiremos usando estas estrategias hasta en la universidad”, comenta Natalia. “Yo siempre usaré lo que aprendí al crear mis cuadernos interactivos. Por ejemplo, sé como tomar los apuntes necesarios para estudiar y como usar ilustraciones detalladas al aprender nuevos conceptos. Ya hemos aprendido a aprender”, concluye Eva. DLeNM Promising practices... —continued from page 7— The VISITAS process has had a lasting impact on our instructional practice at Coronado. As María de la Torre, a first grade teacher, described her learning, “I wanted to improve my students’ ability to talk to each other about what they were learning. VISITAS helped me look at what the students were doing and how my instruction changed, especially in questioning and academic conversation.” Through VISITAS, we found a focus on academic conversations and our students are now better able to meet CCSS objectives while developing Spanish literacy and speaking skills—we see the evidence to support this. While kindergarten classrooms focus primarily on vocabulary development in Spanish, first grade students use sentence frames to explain math strategies and state opinions. By second grade, it is not uncommon for a student who spoke no Spanish when they started Kindergarten to be able to share their thoughts in Spanish without resorting to English to express themselves. Teachers advise these students who are struggling in Spanish, but producing sustained discourse, by reminding them, “You’re learning how it sounds. To learn a language you have to use it.” By third and fourth grade, students are better able to use these new skills to focus and deepen their conversations by elaborating and clarifying, and building on each other’s ideas. By fifth grade, students expect to be challenged to support their ideas by giving evidence from the text. We also find that students are more eager to use the skills for academic conversations in English once they have learned them in Spanish. The VISITAS process has not only helped us improve our teaching practices, it also benefits our students by creating equity of voice, so the quiet ones talk more, and the talkative ones learn to listen. collaboration, and direction to help students take ownership of the Spanish language and develop their skills in academic oral and written discourse in both English and Spanish. City, E., Elmore, R. F., Fiarman, S. E., & Teitel, L. (2009). Instructional Rounds in Education: A Network Approach to Improving Teaching and Learning. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Cummins, J. (1996). Negotiating Identities: Education for Empowerment in a Diverse Society. Los Angeles, CA: California Association for Bilingual Education. Zwiers, J. & Crawford, M. (2011). Academic Conversations: Classroom Talk That Fosters Critical Thinking and Content Understandings. Portland, ME: Stenhouse Publishers. Thank You La Cosecha 2015 Top Sponsors! Soleado—Fall 2015 Our experience supports the research claims about the benefits of developing biliteracy and bilingualism. As Cummins (1996) states: Teachers check in briefly for clarity and consistency between classroom visits. …literacy in two languages enhances the intellectual and academic resources of bilingual students. At an instructional level, we should be asking how we can build on this potential advantage in the classroom by focusing students’ attention on language and helping them become more adept at manipulating language in abstract academic situations. (p. 170) In the coming year, the VISITAS approach to professional development will continue to provide Coronado Elementary staff with the tools, ¡Muchísimas gracias! DLeNM 15 Soleado—Promising Practices From the Field—Fall 2015—Vol. 8, Issue 1 Dual Language Education of New Mexico 1309 Fourth St. SW, Suite E Albuquerque, NM 87102 www.dlenm.org 505.243.0648 Executive Director: David Rogers Director of Business & Development: National Association for Leslie Sánchez Multicultural Education Director of Programming: (NAME)—Past Achievements, Lisa Meyer Present Successes, Future Aspirations: October 1–4, 2015, in ; Board of Directors: Chairpersons— Loretta Booker Jesse Winter Board Members— Isaac Estrada, Esq. Mishelle Jurado Dr. Sylvia Martínez María Rodríguez–Burns Barbara Sena Nick Telles Flor Yanira Gurrola Valenzuela ... la educación que merecen todos nuestros hijos. Editor: Dee McMann [email protected] © DLeNM 2015 All rights reserved. Soleado is a quarterly publication of Dual Language Education of New Mexico, distributed to DLeNM’s FUENTE365 participants. It is protected by U.S. copyright laws. Please direct inquiries or permission requests to [email protected]. New Orleans, LA. For more information, visit the NAME website at nameorg.org. ; Association of Latino Administrators & Superintendents (ALAS)—12th Annual Education Summit: October 14–17, 2015, in Albuquerque, NM. For more information and to register for the conference, please visit alasedu.org. ; Texas Association for Bilingual Education (TABE)—43rd Annual conference—Biliteracy ¡Ya es hora!: October 14–17, 2015, in El Paso, TX. Please visit txtabe.org to learn more. ; World Class Instructional Design and Assessment—WIDA 2015 National Conference: Pride in Language—Learn, Reflect, Act: October 15–17, 2015, in Las Vegas, NV. For more information, visit WIDA’s website at widaconference.us. ; Achievement Inspired Mathematics for Scaffolding Student Success (AIM4S3™)— Level I Training: October 20–22, 2015, in Albuquerque, NM. This training will have a middle school focus, and space is limited! At $459 per person, the training includes model overview, theory/ research, supporting data, classroom demonstrations, and planning time. Contact Lisa Meyer, [email protected], for more information. ; Dual Language Education of New Mexico—20th Annual La Cosecha Dual Language Conference: November 4–7, 2015, in Albuquerque, NM. Join us for our 20th anniversary conference! Register by September 25 to take advantage of regular registration rates. For La Cosecha 2015 Schedule of Events, Featured Speakers, and all the latest conference information, visit http://dlenm.org/lacosecha. ; Center for the Education and Study of Diverse Populations (CESDP )—24th Annual Back to School Family Institute—The Many Languages of Family-School Partnerships: November 6-7, 2015, in Albuquerque, NM. Families are encouraged to attend! To learn more, visit www.cesdp.com. ; Project GLAD®—Tier I Certification: December 3-4 (TwoDay Research and Theory Workshop) and December 7-10, 2015 (Four-Day Classroom Demonstration), in Albuquerque, NM. This DLeNM-sponsored training will have a middle school focus, and space is limited! For more information and to check availability, please contact Diana PinkstonStewart, [email protected]. ; Illinois Resource Center (IRC) and Illinois Association for Multilingual Multicultural Education (IAMME)—39th Annual Conference for Teachers Serving Linguistically and Culturally Diverse Students: December 8-11, 2015, in Chicago, IL. For more information, go to http://www.thecenterweb.org/irc/pages/f_ events-bilingual.html or call 224.366.8555. Soleado is printed by Starline Printing in Albuquerque. Thanks to Danny Trujillo and the Starline staff for their expertise and support!

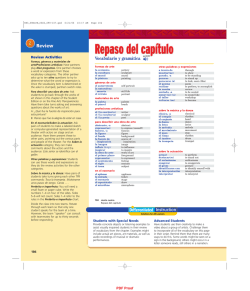

© Copyright 2026