Work-life balance

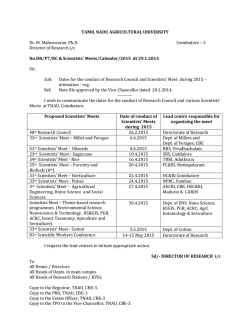

EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com Work-life balance A EuroScientist Special Issue – January 2015 Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org 28/01/2015 EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com 28/01/2015 Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Editorial ........................................................................................................................................................................... 4 European scientists: too often, like acrobats without a net ......................................................................................... 4 Living on the edge ........................................................................................................................................................... 6 The science of sleep, the sleep of scientists ................................................................................................................. 6 Work-life balance on hold, for the love of science ....................................................................................................... 9 Solutions for better life ................................................................................................................................................. 12 Inadequate childcare policies affect scientists' careers.............................................................................................. 12 Mobility more attractive due to new pan-European pension pot .............................................................................. 16 Personal options in science careers ............................................................................................................................ 19 Wider world perception ................................................................................................................................................ 21 When real science falls short in Hollywood ................................................................................................................ 21 Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com 28/01/2015 Introduction Welcome to this special issue of EuroScientist on work/life balance! We have a unique selection of articles to share with EuroScientist readers the kind of extremes of work pressure that scientists can be subjected to—be it by working in extreme environments or because they are sleep deprived. Find out how some of the people interviewed for these articles are prepared to temporarily tilt their work/life balance towards more work and less time for themselves for the love of science. In another section of this special issue, we explore the kind of solutions that have yet to be implemented to make life easier for scientists. This is particularly the case when it comes to inadequate levels of childcare across Europe. Find out how policy decisions could certainly be made in most European countries to make it easier for parents to juggle work and life. Further policy decisions have yet to be made concerning pension arrangements of highly mobiles scientists. One new initiative covered in the issue, despite its limited scope offers food for thought on how best to encourage scientists to be mobile without losing out on pension arrangements. Looking further afield, we explore one practical approach, based on what could help make researchers’ careers more controlled by building options. And finally, we provide you with a reflection on how scientists’ private life is portrayed in films. It examines how directors too often succumb to the temptation of dramatizing famous researchers’ lives at the expense of providing a portrait close to reality. This brings to the question of whether mass media such as movies serve the cause of science and its relationship with the public by changing its historical representation. Enjoy this issue and don’t forget to write to [email protected] or to comment below each individual article, to tell us about how you feel about your own work/life balance. Photo credit: Sunset Slackline from Shutterstock Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com 28/01/2015 Editorial European scientists: too often, like acrobats without a net By Sabine Louët Published on EuroScientist: www.euroscientist.com Juggling work with the demands of personal life may lead to compromises in research careers As we are still early in the New Year none of us escapes the need to plan. As a result of such plans, the need to juggle becomes more pressing. We all try to master the art of arranging in a skilful manner the professional and the private spheres of our existence. Some have too much work. Some have too much time on their hands. Some balance the two in a manner that they did not know they could. The majority are paying a high price on their private life—let alone depriving them of sleep—for a career in research. More often than not, they are facing the consequences of living with precarious research positions and facing the constant need for high mobility. In principle, mobility is one of the greatest advantages of doing research. It broadens your horizon, enhances your experience. The trouble starts when it is not simply just you on your own. For dual career Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com 28/01/2015 couples, for example, there is often one person left behind. Having to compromise so that the other can progress in their research is often the only option. The move will balance out in the long term, as long as it is not always the same person who makes the sacrifice. Thus, the context in which European scientists operate has deep implications for family life. Not having stability, makes many postpone plans to have children, for example…Those children, who, once born, will not necessarily find adequate childcare structure to welcome them once both parents go back to work. Each researcher therefore needs to keep their options open and stop worrying about whether they will stay in research until they reach retirement. So many scientists across Europe are faced with this kind of dilemma. Even more so now that some country’s research budget are been scaled back; resulting in decreased opportunities for careers in research at all. Now, after years of recession, the seriousness of the situation has reached new heights. Many scientists are turning their back on a career in research. Out of necessity. Some seek refuge in the private sector, working as developers in the software industry or project managers in the biotech sector. Others will simply find a niche and set-up their own technology start-up. These are the lucky ones; they still work in a field in which they can apply the skills they have learned as scientists. Others change tack completely. Real life examples of unlikely career paths involve former scientists setting up a therapeutic massage practice, or becoming secondary school teachers. All of the decisions to try and make a decent living—and balancing both their work and life—are laudable. Yet this is not exactly the plan they had when they started out. Nor does it provide fodder for the kind of scientist’s biopic that Hollywood is so keen on. But if this is the only way researchers will adapt to their unforgiving environment, so be it. To make it possible for many more researchers to take that step, it would be necessary for the rest of the economy to acknowledge their worth, their creativity and their adaptability, which is not often the case in European countries. Otherwise, they become like acrobats trying to impress without a net. In the event of a fall, the consequences may be brutal. Photo credit: hbp_pix Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org 28/01/2015 EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com Living on the edge The science of sleep, the sleep of scientists By Vanessa Schipani Published on EuroScientist: www.euroscientist.com Sleep is key to having a fresh mind, yet, many scientists do not have the luxury of a full night’s rest Sleep. We all need it. From working long hours in the lab or field, researchers often get much less sleep than the average person requires. Conducting research into the twilight hours is prevalent in all fields of science, from life science to particle physics. But the cognitively demanding tasks of conducting experiments and analysing data require a clear mind. So how do scientists manage their research—let alone their personal lives—with little rest? Here, a few scientists share lessons about sleep they have learned from their life and work. Teamwork around the biological clock Unlike the typical nine to five job, an owl ecologist's work day begins at sundown, when their avian subjects are most active. But for researchers who study the circadian cycle of organisms or particles in accelerators, experiments must often run day and night, due to high demand for such equipment. And let us not forget the mathematicians so Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com 28/01/2015 engulfed in solving problems, they crunch numbers into the twilight hours. Sleep often take a backseat in science, but to manage sleep deprivation researchers in both physics and medicine say working with others prevents careless mistakes and wasted time. "Synchrotron measurements are intense because you get a limited amount of time to use the machine, so you want to take advantage of every minute," says Karsten Rode, a Norwegian physicist based at Trinity College Dublin in Ireland, who uses synchrotrons to characterise new materials. Although their experiments run day and night, Rode and his group take advantage of the fact that people have different circadian rhythms: the larks take the early morning shifts and the owls run experiments at night. "You can't go it alone," says Rode. "Our experiments, science in general, have to be a group effort." One expert concurs with the approach of Rode's group: "For productivity it doesn't matter if you're an owl or a lark. You get the most out of your time if you just follow your own inner pattern," says Urs Albrecht, a researcher of circadian rhythms at the University of Fribourg in Switzerland. Working close to others also avoids wasted time. "If you're awake for roughly 24 hours straight, it's the same as having one promille of alcohol in your blood," which is over the legal driving limit for most countries, says Päivi Polo, a physician and sleep researcher at Turku University Hospital in Finland. Just like an intoxicated friend who believes he or she is fit to drive, Polo says it is "sometimes difficult to see how sleep deprivation affects your ability to work efficiently and effectively." Rested colleagues let her know when she's mindlessly "moving things from one place to another without accomplishing anything," and she does the same for them. Adrenaline rush One of the ways we combat sleep deprivation is through our body's adrenergic system, which produces that adrenaline rush in moments of danger or excitement. This system turns on when we spot a lion, or for scientists, perhaps when their data beautifully matches their hypothesis. "If you have the motivation and excitement to work you can get over the fact that you're dead tired," attests Polo. Albrecht emphasises that chronically overusing our body's adrenergic system can have detrimental effects on health. "Your mood, metabolism and circadian rhythm [are] interconnected," he says. "If we don't live according to our own internal cycles, this [heavily disturbs] our metabolism,” he adds, [this then] “causes the development of metabolic diseases like obesity and mood disorders like depression." While enthusiasm is vital to the progression of science, Rode says scientists as a community need to get away from drastic levels of dedication. "Some people have this romantic view of researchers as committed only to the beauty of fundamental science. This is true to some extent, but it's also a job," he adds. "All of the researchers I know work much more than the 38 hours they're paid for." Life lessons from research Rode says shift work at synchrotrons may have given him a little head start when it came to learning how to be a father. "Some new parents try to keep a normal habit of going to bed at 10pm and getting up at 6am, but babies sometimes want to sleep between 6pm and 12am," he says. "When you've done shift work before, you know that if you've got the time to sleep between six and midnight, then you learn to sleep then." As a scientist who studies the body's cyclical pattern it is no surprise Albrecht sees the relationship between his work and life as a feedback loop. But maybe his insight could benefit all scientists. "My research impacts my lifestyle and my lifestyle impacts my work," he says. "Almost every day at lunchtime, I go running. I move, I get [exposure to] light, I reset my metabolism and send a strong signal to my circadian system. This all helps me to sleep better. And when I sleep well, I'm a much more productive researcher the next day." Albrecht is not alone in this view. Over one thousand years ago the ancient Greek philosopher Plato offered similar advice in his dialogue Timaeus: "When the mind is too big for the body its energy shakes the whole frame and fills it with inner disorders...when a large body is joined to a small and feeble mind...the soul is afflicted with the worst of all diseases, stupidity. There is one safeguard against both dangers, which is to avoid exercising either the body or mind without the other, and thus preserve an equal and healthy balance between them." Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com Photo credit: Svein Halvor Halvorsen Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org 28/01/2015 28/01/2015 EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com Work-life balance on hold, for the love of science By Costanze Böttcher Published on EuroScientist: www.euroscientist.com Scientific research in remote areas leaves little room for private life but the attractiveness of such extreme work environment prevails It is the end of your working day. And you are ready for a break. But what if there is nowhere to go and family and friends are far away? This is precisely what happens to scientists working in remote locations, such as polar research stations or oceanographic research vessels, or even the international space station. They can hardly escape from work. This lifestyle puts the work/life balance under a lot of pressure. But those involved would not trade such temporary inconvenience for anything as the personal rewards of doing research in extreme environment are also high. Scientists may benefit from this first-hand experience throughout their professional lives. Challenging lifestyle Conducting scientific fieldwork in, say, Antarctica is physically and technically challenging. “Lab scientists can simply go home. We cannot do that,” says Sabrina Heiser, a marine biologist currently working at Rothera, one of the British Antarctic Survey (BAS)’s research stations. It is hardly accessible during austral winter. During periods of bad Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com 28/01/2015 weather in winter, the staff may not be able to conduct fieldwork for three to four weeks, according to Heiser. “This can be very frustrating. It is important to keep up the daily routine and find something useful to work on,” she adds. Scientists in other remote locations, such as the Zackenberg Research Station in the Northeast Greenland wilderness, experience similar strain. “A normal working day lasts about 14 hours,” says Morten Rasch. “There is not very much to do except for working and, maybe, reading a book.” Rasch is a senior advisor at the department of geoscience and natural resource management at the University of Copenhagen, Denmark. He managed Zackenberg from 1997 to 2012. He also chairs the international Arctic station manager forum INTERACT. Onboard ships for oceanographic expeditions, the conditions are comparable. “The particular challenge in conducting open ocean research is that you often only have a single opportunity to get things right,” says Robert Turnewitsch, principal investigator in marine geochemistry at the Scottish Association for Marine Science in Oban, UK. “This puts your work under certain pressure,” he adds. Close-knit community Working with small isolated communities of researchers force scientists to learn to adapt to their situation. For example, while about 100 people work in the BAS’ Rothera station in the summer, only 20 scientists and technical staff stay over in winter. “We work and live closely together. And [we] have to find a way to get along with each other,” Heiser points out. But in her experience, serious problems seldom occur. On the contrary: “You make friends for life. Particularly during winter, the team becomes a big family,” she notes. At the other end of the world, on Svalbard, the Norwegian archipelago in the Arctic Ocean, “scientists share a similar experience. Ny Ålesund is like a small village. You need to be open-minded to integrate into the community. But you also make new friends,” says Verena Mohaupt, a physicist who currently manages the French-German polar research base AWIPEV in Ny Ålesund. There, about 30 scientists and technical staff from different nations operate several research stations during winter. Cherished privacy Despite the support of the close knit community of work colleagues, sometimes the need for privacy and relaxation have to regain their rights in such a demanding work environment. To recover from work, “it is important to find time for yourself,” Mohaupt notes. She particularly likes spending her spare time in nature. This is even possible in winter when the sun does not rise over the horizon for about four months, she says. Moreover, “the community is quite active. There are lots of possibilities to relax, such as doing sports,” she adds. Other concur that finding personal time to relax is thus particularly important. “Luckily, there is a lot you can do,” Heiser says. For example, there is a library, a music room and a TV room at the station. Each Saturday thos working at the station dress up for a more formal dinner. “And you can go skiing, snowboarding or climbing,” Heiser adds. However, after having spent two years at the station, Heiser also appreciates having a room of her own during the winter months. This allows her to retreat and keep some privacy. “It is such small things that matter,” she points out. Similar to the better-equipped field stations, ships for seagoing expeditions in fact offer lots of possibilities to relax. “Most of the modern vessels have social rooms, a fitness room or even a swimming pool,” says Turnewitsch. In addition, small activities such as informal chats with other researchers, birthday parties or small trips with a boat, break up the daily routine aboard and help relieve this pressure. Personal reward Despite challenging work conditions and the lack of privacy, all scientists regard their work in these extreme environments as particularly rewarding. “You get to see places that others do not have the chance to see,” Turnewitsch says. Rasch shares a similar experience. “I am addicted to the Arctic. And I like being in a remote place,” he says. Heiser agrees. “Working in Antarctica is a dream job. It is incredibly beautiful here,” she says. Heiser will have spent two and a half years in Antarctica when she is finally leaving Rothera in April 2015. She adds: “Then, it is time to return home. Of course, I miss my family and friends. And I am looking forward to warmer weather and to seeing trees gain. But I will also greatly miss everything [here at Rothera].” Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com 28/01/2015 As in the case of Heiser, mainly passionate early career scientists nowadays forgo private life to stay for longer time periods at extremely remote places, Rasch points out. “It is often young PhD students who maintain the remote field stations [in the Arctic]. Senior scientists do not have the time,” he says. These young people “are extremely happy to work in the Artic”, Rasch adds. “And they can’t really understand how fast time flies,” he concludes. Rebalancing home life Despite all the attractiveness of fulfilling research goal in some of nature’s most spectacular settings, there is a potential backlash. People often get stressed out without noticing after having stayed far from home for more than two months. “Life on these stations is like on a ship. And people can become very homesick and frustrated,” Rasch says. This is the reason why the staff usually only stays for two months at such isolated places on Greenland, he explains. However, when it comes down to balancing family life and field research, “we need to reorganise our daily routine at home,” Turnewitsch points out. By contrast, in Rasch’s view, as a field researcher “you really get into a dilemma when you get kids.” Strolling polar bears are among the reasons why children under the age of 16 are not allowed at remote field stations on Greenland, he points out. Rasch himself was away during summer in most years. This was possible because he has a “very supportive wife”, he says. But not until his children had reached an age of 7 and 9 did he realise that he missed important bits of their life. “I had a wake-up call when I got ill one summer and was forced to return home,” he says. Since then he has restricted field trips to shorter time periods. All scientists agree that they need to carefully plan their research and be able to deal with issues arising in such remote work environment in a creative way. But, as Heiser stresses, tackling these challenges and having had the chance to learn to know people in a very particular way have immensely strengthened her. Working and living in Antarctica, she concludes: “has advanced my personality and my professional skills profoundly.” Photo credit: Awipev Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com 28/01/2015 Solutions for better life Inadequate childcare policies affect scientists' careers By Janna Degener Published on EuroScientist: www.euroscientist.com The inadequacy of childcare policies across Europe, means that scientists who do not wish to be away from their lab for too long are struggling to balance their life as parents and as researchers. There are still some significant decisions concerning harmonisation of such childcare provision to be made in Europe, while further policy support would be welcome. Being able to perform scientific research while raising children is a balancing act that requires highly flexible work arrangements, and could do, in many countries, with additional policy support Pauline Mattsson loves her job as a guest postdoctoral researcher at the WZB Berlin Social Science Center, funded by the Swedish Research Council. And she works hard to get ahead in her career. As a mother of two, she recognises the flexibility of her scientific occupation. She can live in Berlin, Germany, with her family even though she works for Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com 28/01/2015 a Swedish university, the Medical Management Centrum at Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm. Every day she tries to spend a couple of hours of the afternoon with her kids and when they sleep at night or on the weekends she goes back to her desk. “I could not live the life I am living if I was not doing research,” Mattsson says gratefully. Still, it is a big challenge for her to manage both her scientific career and the children. The problems started arising when the kids were born. Back then, Pauline and her partner could not find a kindergarten for the babies. “In Sweden and Germany the system is very generous as long as you stay home until the kids are one year old. But as a scientist you cannot take a year off, as you would be getting off from research,” Mattsson says. That is why, after the births of her children, she tried to continue working at home while taking care of her babies. With her first child she could work full time again after seven months because her partner then stayed at home. And the second child was looked after by a babysitter when she was four months old, even though this was a costly solution. “The system doesn’t support families in the cases where parents want/have to start working before the child is one. It is very difficult to find public childcare for children below one”, Mattson says. Inadequate childcare Of course, Mattsson is not alone. What’s more, the inadequacy of childcare provision, not only affects women, but also men. Estimates point to “8.4 % of men and 21.1% of women between 25 and 54 years old were inactive in 2012 due to the presence of young children in the family,” says Barbara Janta, analyst in the employment, education, social policy and population team at consultancy RAND Europe, based in Cambridge, UK. She referred to the reports on the Use of childcare in the EU Member States and on Caring for children in Europe. “It is true to say that childcare responsibilities still affect women to a much greater extent than men. In contrast, fathers have higher rates of employment compared with childless men.” The issue is largely a cultural one. “It is not due to science but due to the cultures of the different countries that the problem of childcare is more on the shoulder of women than men. But the role models and the family models are changing slowly and that affects scientists and other high educated women,” says Claudine Hermann , vice-president of the European Platform of Women Scientists, retired professor of physics at the Ecole Polytechnique in Paris, France, with three children. Hermann claims that scientific institutions should invest more money to support female and male scientists with children to compensate the fact that the number of scientists with children varies much from country to country. Indeed, limited, inadequate or overpriced childcare provisions in some European countries appears to be seriously detrimental to scientists’ careers. Even though it is impossible to generalise the issue for the whole of Europe, due to the disparity of childcare systems in place, the devil is in the details. Even when publicly funded childcare is available, that may be the case only on a part time basis. Thus, complicating the equation for working scientists who need to call upon complementary privately arranged childcare services. Barcelona targets Many studies deal with the arrangements and perspectives of childcare systems in the EU. And the European policy makers have long recognised the issue in general terms. Back in 2002, they established the Barcelona targets, to improve the employment rate of young children’s parents to achieve greater gender equality in the workforce. Their aim was, by 2010, to provide childcare to at least 90% of children between 3 years old and the mandatory school age and at least 33% of the children under three. This aim was not met by all the EU member states. And the childcare systems in some countries allowed parents only to work part-time. “If you think of the Netherlands for example that seem to be progressive in meeting all of the requirements, you see that a lot of women are in the labour force but overwhelmingly in part-time jobs,” says Melinda Mills, professor of sociology at the University of Oxford, UK who evaluated the achievements of the Barcelona targets. “So even though the Netherlands meet the targets in some ways, they actually don’t fully integrate women as equals into the labour force.” Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com 28/01/2015 For scientists, who double up as parents, part-time work is generally not an option anyway because the competition is high. “In some countries, people with part-time jobs get insurance benefits and work protection like fulltime workers so that they are in a less marginalised position,” says Melinda Mills. “As a full professor and academic I know that once you achieve a certain level in academic or other organisations it is very difficult to hold a managerial position if you work part-time,” notes Mills. Informal childcare is often not a viable option for scientists either because they are expected to be internationally mobile. Grand-parents normally do not typically live nearby. And contacts with neighbours takes time to develop, Mills says. Therefore, scientists with children often work fulltime in order to meet tenure track criteria and sometimes to fulfil their ambition to be eligible to become a professor. They benefit from the flexibility of working hours and places. But this autonomy goes hand in hand with the tendency to overwork that has the potential to harm health and family relations. Emulating best practice Childcare systems across Europe therefore need to become adequate, affordable and flexible enough to provide reliable support. And this is necessary, not only for scientists with children, but for other professionals who don’t want to or who can’t afford to stay at home or reduce working hours: “The system should support and encourage families that don’t follow the norm,” Mattson says. But there is still a long way to reach this goal. The trouble is that childcare systems in Europe still differ enormously, in quality and quantity – mainly due to historical reasons. However, some best practice models have been tried and tested. According to a 2007 European Parliament report, called The cost of childcare in EU countries, the most effective policies are those that offer a combination of maternity/paternity leaves for the period immediately following birth, and part-time jobs and childcare facilities for the following years. That’s the case in the Nordic countries, for example, according to Willem Adema, senior economist in the social policy division of OECD Paris, France, leader of a team of analysts of family and children policies and responsible for the online OECD Family database. There, the States try to provide a continual of support throughout early childhood by paying parental leave of around one year. Finland, for example, has Home Care leave until the child is three years. In Scandinavian countries, this approach of often complemented by systems of childcare support until children enter primary school at age 7, and a system of out-of-school hours care for school children up to age 11 or 12. As a result, the EP report states, both fertility and female participation rates are very high. Meanwhile, the negative effects on women’s career and income perspectives seem to be rather modest. France has a similarly comprehensive support system especially when it concerns children age 3 years and over. Meanwhile, the country has been reducing the duration of the primary school day and making local authority responsible for offering childcare in the form of supervised after school activities. By contrast, in Southern European countries, there is a greater informal care support, often by relatives. This is change from countries like the Netherlands, Germany, Switzerland and the UK. There, people are more likely to find work-life/balance solutions by reducing their working hours, and many women work part-time in these countries. By comparison, countries in Central and Eastern Europe, such as in Czech and Slovak Republics and in Hungary, often have very long periods of paid leave before children enter pre-school according to Adema. And they experienced a clear downward tendency with regards to childcare facilities during the 1990, according to a comparative review of 30 European countries. “In some of these countries the (economic and social) climate for childcare services has improved over the last few years but in others shortages remain. Clearly, harmonisation at the European level is needed. According to the 2007 report, entitled The Cost of Childcare in EU Countries, this is true for the quantity and quality of the supply of care services, the affordability of care services for families among others things. Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com 28/01/2015 In line with such wide diversity of approach to childcare, the social acceptability of relying on childcare facilities differs across European countries. In her social environment, in Germany, Swedish scientist Pauline Mattson often feels misunderstood: “I don’t know any family in Germany where both men and women are working fulltime. People often discuss what is best for the children but I don’t think that children staying home with their parents until they are a year and a half old are happier than children in countries who spend more time in formal childcare especially for children below one.” Photo credit: Phil Dowsing Creative Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com 28/01/2015 Mobility more attractive due to new pan-European pension pot By Anthony King Published on EuroScientist: www.euroscientist.com The first pan-European pension scheme for highly mobile scientists has been launched The European Commission had identified pensions as a big obstacle for the mobility of researchers in Europe. So it has launched a pilot scheme, designed to facilitate the delivery of a pension fund for highly mobile scientists in Europe. The sheme is called RESAVER, which stands for Retirement Savings Vehicle for European Research Institutions. Following related feasibility studies and workshops, the Commission is now investing €4 million to guide it through its first four years. It should eventually permit scientists to carry a pension pot between countries in the European Economic Area, without disruption. But it will not take the place of state-run pensions. Instead, it will provide supplementary retirement income paid for through employer and individuals’ contributions. The consortium, which manages RESAVER, was formerly established in October 2014, with seven founding members, from Hungary, the Netherlands, Austria and Italy. These included Elettra Sincrotrone Trieste, the Technical University of Vienna and the Central European University of Budapest. More are expected to join in. “Around 300 institutions have contacted us. In the course of 2015, I expect between 10 and 20 new members of the consortium, with three very close already,” says Paul Jankowitsch, chairman of the board of directors for RESAVER, who is vice-rector for finance at the Vienna University of Technology. Italy’s National Research Council (CNR) is expected to join soon. “We’ve also had some interest from private chemistry companies too.” RESAVER will be open to all organisations with a substantial research element. Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com 28/01/2015 RESAVER benefits In January, UK-based pension consultant Aon Hewitt, was appointed to provide support for this new cross-border pension, which is structured as an IORP in the jargon; which stands for Institutions for Occupational Retirement Provision. “As long as their employers are members, researchers will know that they can join this scheme, which provides consistent benefits across all countries, so you won’t need to get to grips with a local scheme,” explains Jacqueline Lamont, consultant at Aon Hewitt, based in London. It is likely that individuals, as well as employers, will contribute to the scheme in most cases. Proponents argue that economy of scales will make the scheme competitive and attractive. “Organisations will have access to a best-in-class defined contribution pension fund and they are going to be able to offer this to their employees. By doing that they should be able to attract the best researchers to their organisations,” Lamont says. Jankowitsch predicts RESAVER will compete against local and national pension scheme for members. And RESAVER needs to be widely adopted for its merits to be felt across Europe. Indeed, if it gains momentum, it will be difficult for employers to ignore. “When a researcher considers moving, knowing an employer has got RESAVER can make it instantly more attractive,” says Lamont. The pension itself will be run from one country, possibly the UK, Ireland, Luxembourg or the Netherlands, though Belgium looks likely. An investment advisor is to be hired this year, and a RESAVER website will be launched within the next six months. Mobility no longer penalising pensions The scheme is not about equalising benefits. It will not allow someone take benefits from a country they have worked in, such as an earlier retirement date. Nonetheless it should fix an unfair quandary that arose when Europe promoted mobility but left individuals in the lurch in terms of pensions. “This is something that all of us researchers who have been quite mobile in Europe have been looking for,” says Luisa de Cola, professor of supramolecular and biomaterial chemistry at the University of Strasbourg in France, adding: “when you change countries it is impossible to transfer the pension.” She lived for 11 years in Italy, 6 years in Netherlands and 7 years in Germany and now works in France. “I wasn't even able to transfer my pension from Germany to France,” adding that her pension has been left inadequate. “This is a problem that affects hundreds of scientist. It is a big issue,” she adds. Whether RESAVER will allow pensions to amalgamate under this one new pan-European scheme is a complicated question. There might be an option to transfer funds from an old pension into RESAVE, says Lamont, ‘but that would need to be looked at on a case-by-case basis.” Another essential component of RESAVER will be country committees. Institutions must still follow social legislation and collective practices in their respective countries. Country specific sections will ensure compliance with local regulations. So far, the Italian committee is the most advanced. Country variations for retirement The plan is for nine countries to join the scheme over the next four years. However, there is huge variation in pension regulation between countries. Some countries will find it easier to adopt than others. In France, for example, full time researchers and professors are civil servants by law, so do not need such a supplementary retirement pension, says Jankowitsch. But not all French researchers are civil servants. Private research institutions are interested in the scheme and the consortium is consulting with the appropriate French ministries. The situation in Germany is more intractable, as it will take legislative changes. Indeed, supplementary retirement pension arrangements are run on a federal basis. This means that even moving pensions within Germany can be tricky. By contrast, the UK has its own pension for higher education institutes, called USS, and UK universities cannot joint the new scheme. “There has been some interest from the charity sector,” says Idi Seehra research fellow in human Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com 28/01/2015 resource strategy at the London School of Economics, in the UK, and member of the RESAVER task force. “For universities you can join USS and then if you wish to move to another country you can transfer to RESAVER. Someone might argue that this doesn't sound so attractive, but that would be a point for institutions to address in future.” Others point to financial difficulties in the USS and believe the UK will likely join. Evolving pan-Europe pension initiatives The Belgian-based League of European Research Universities, LERU, provided the Commission with feedback throughout the process and welcomes the initiative. “In theory there are coordination mechanism that are supposed to help researchers with their pension when they move, but in practice it turns out to be difficult,” says Katrien Maes, chief policy officer at LERU, in Leuven. She praises the Commission’s role for cradling the pension scheme. “It’s been a long process, but I think that is to be expected given the complexity of the material we are dealing with. This is a really innovative scheme.” The Commission itself reckons that something like 30% of all researchers have been mobile for the last 10 years and recognises that these people have run into problems with pensions. A private pension option—in addition to state pension and supplementary retirement pension—will be available for researchers who work for organisations but do not have employment contracts, such as those receiving grants. Photo credit: © fotomek - Fotolia.com Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com 28/01/2015 Personal options in science careers By Haydn Shaughnessy Published on EuroScientist: www.euroscientist.com Jack is learning to live with his mistakes. A thirty three year old social media junkie—working as a freelance or, in reality, as a small company--he has just blown a year of his life after taking on the wrong project. Wasting valuable career time on wrong options is a risk we all face. It is becoming commonplace in career paths with no wellestablished structure like social media. But it is a risk for people in research too. Specifically, how can we learn to translate experience into better options? How could someone like Jack or you plan better? The answer lies in the way we create and manage our options. Options building is one of the crucial aspects of how we navigate the digital economy. Most of us could do with a survival guide for the 21st century economy. That’s because the digital economy is not just about new technology. Dramatic changes are taking place in how people work together, how they think about society and wealth, and the risks and options they face in employment and business. As a result, we are functioning within new structures with their own logic. We therefore need to quickly learn to adapt to them. Take open source software, for example. Its community has grown a meritocratic structure that helps people build careers. And it has, in turn, helped the community become a powerful force in the economy. As a result, the growth of open source software code lines is phenomenal. The pace of growth exceeds that of Moore’s Law, the law that says computer processing power doubles every 18 months. The pool of open-source code lines doubles about every 10 months. Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com 28/01/2015 That spells a powerful presence, though a little understood one. The new cryptocurrency BitCoin is an expression of that power. Bitcoin is global. It has an underlying connected community in excess of 75,000 people and entities. And it is bigger than the conventional and alternative payments communities put together. It is so big because it is an expression of value through code. Part of its success lies in the fact that coders are a global community. This is where there are synergies with the research community. Indeed, scientists too form a global community. This community could learn from open source, at least in terms of realising the gains of progress for its members. In particular, scientists need to learn how to create options. To do so, we need new ways of understanding how we invest – whether the investment is time, money or energy. We also need to think carefully about the communities within which we are embedded. Open source began as an evangelical movement and it is working out well for people who need alternative ways to do their career building. Open science could do the same for science careers but more important is the shift in mindset. Researchers need to wonder: what options are you investing in today? People have to take more decisions but in conditions of uncertainty and increasing complexity. And their judgments will be more often wrong and often only partially right. In fact it might be that we dispense with the concept of right and wrong in our careers. Instead, we need to seek new ways to balance the impact of decisions and what we can learn from them. This prediction and feedback-based approach is in itself not intrinsically new. It has, incidentally, been the object of many scientific endeavours, sometimes referred as complex systems, and led to the development of many predictive models. The truth is that it is inevitable in the new economic environment that we are going to be wrong more often than we might have been in the past, when handling critical career and life decisions. There is a discipline that can help – real options theory. In real options theory analysts try to replicate the put and call practices of financial traders. The objective though is to anticipate what it costs to make any decision. If you are going to embark on route A instead of route B, what are you potentially ruling yourself out of? If you can clarify this, how can you hedge against route A failing and route B being lost to you? Recognizing that your life and career is more of a market than you might wish it to be, at least gives you a start on building your career as a set of simultaneously balanced options. I apply this principle in my own consultancy-based work, and it could apply to the way scientists manage their time and efforts as well. In my own experience, I always know I am going to do work for free. But I put a cap on that of one week a month. I allow myself to do a further week of lower paid work that offers scope for future growth. I then try to do the main job for a week and use the final week to aim for highly-paid consulting or speeches. It takes time to build options and I don’t want to close them down prematurely. My pricing mechanisms allow me to manage them. And increasingly my choice is dictated by long term pay-offs. In other words, I am my own best long term investor. It feels good. Photo credit: Lauren Macdonald Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org 28/01/2015 EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com Wider world perception When real science falls short in Hollywood By Vanessa Schipani Published on EuroScientist: www.euroscientist.com When truth and drama battle it out in the scripts of blockbuster films about the lives of scientists, drama often wins The lights dim and five modest words flash across the theatre screen: 'Based on a true story.' But what does this phrase aim to convey? Fact or fiction? The lives of influential scientists are often in Hollywood's limelight, especially as of late with the release of films such as The Imitation Game about mathematician Alan Turing and The Theory of Everything, a portrait of cosmologist Stephen Hawking. But filmmakers have been producing biopics, or biographical films, about science's most eminent figures since the 1930s, from The Story of Louis Pasteur in 1936 to Creation, a film about Charles Darwin, in 2009. These movies have the capacity to reach millions, but they tend to dramatise actual events. Do major films about respected researchers help or harm the public's understanding of science? In this article, EuroScientist explores how the lives of real scientists are portrayed in film in relation to aspects of culture, such as religion and sexuality. Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com 28/01/2015 Stereotyping science The culture surrounding science at the time often dictates which historical scientists filmmakers choose to depict. Today's 'nerd aesthetic' may have influenced filmmakers to tell the story of Alan Turing in The Imitation Game and Stephen Hawking in The Theory of Everything, says David Kirby, a professor of science communication studies at the University of Manchester, UK. These two researchers could be considered "two of the most geek-ified scientists out there," he adds. However, increasingly scientific accuracy is a concern for film producers. Today, researchers are playing an active role in the making of films about science, says Kirby. Science consultants help filmmakers create more well-rounded characters, instead of two-dimensional personas like the mad, socially-inept or omniscient researcher. In this way, Kirby believes the involvement of scientists in filmmaking positively influences the public's understanding of science. But "you still have to tell a dramatic story that's going to bring people to the theatres," he argues. And biopics are no exception. More so than stereotypes, tropes create the dramatic arch seen in most major films. Tropes are recurrent themes in storytelling. For science, a common trope is the scientist struggling against the forces of ignorance. Filmmakers "either choose to depict the scientist, who had this struggle or they will make that struggle the focus of the film – even if it was a minor element in their lives," says Kirby. Forcing the story of real scientists into this dramatic mold can lead to films that are historically inaccurate. But this is not necessarily a problem. "It's more important to be authentic to science or a scientist rather than focusing on accuracy," he adds. While 'authenticity' is a tricky concept to pin down, Kirby equates it with 'plausibility' for films about science and a 'fair portrait' for films about scientists in history. Science and religion Cited by some as authentic, though not entirely accurate, is Creation, a 2009 film about Darwin's lifestyle and relationship with religious belief. "Certain things were invented and changed for that film, but it was authentic to the [religious] struggles Darwin had after the death of his daughter," says Kirby. But some disagree. “The only thing the Creation film got right were the names of the people," says John van Wyhe, a senior lecturer in the history of science at the National University of Singapore and the director of Darwin Online. "It's the most inaccurate and fictitious Darwin film I've ever seen." This disagreement brings up the question of where the line between bending the truth and pure fiction lies. How many small details can be changed before they culminate in an inauthentic film? And can seemingly minor changes still have a large impact on the public perception of an individual scientist or science in general? In Creation, for example, instead of tweaking Darwin's life story, the filmmakers fabricated a clash around religion and evolution between Darwin and his wife and colleagues, says van Wyhe. Creation "imposes our own prejudices and stereotypes onto the Victorians, which does a lot of harm," he says. In other words, Darwin had no conflict between his faith and science, but when films like Creation make it appear as if he did, it feeds today's issues with unjustified support from history. The film also takes the line 'based on a true story' a step further with the subtitle 'the true story of Charles Darwin’—a move that's completely unwarranted, he adds. Science and sexuality Other seemingly small, but significant changes pervade The Imitation Game – some of which unfairly portray Turing as an insane and untrustworthy homosexual and scientist, says Luis Rocha, professor of informatics and cognitive science at Indiana University, USA, who is also affiliated with the Gulbenkian Institute of Science in Lisbon, Portugal. For example, Turing named the machine that cracks the Nazi code 'Bombe.' But in the film he calls it 'Christopher' – named after a childhood friend with whom Turing may have been infatuated. This simple name change implies Turing had an obsessive character, which, in reality, he did not, says Rocha. The film also fabricates a meeting between Turing and a Soviet spy at Bletchley Park, where the spy threatens to expose Turing's homosexuality, if he exposes him as a spy. "The scriptwriters might have thought this would make Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org EuroScientist - European science conversation by the community, for the community www.euroscientist.com 28/01/2015 the film more dramatic, but I think it ends up falling on the cliché of homosexuals as untrustworthy in security situations because of potential blackmail," says Rocha. "The movie also speaks to a wider problem of scientists being stereotyped as closeted people." While The Imitation Game is riddled with harmful historical inaccuracies, "overall a film being made about Turing is a good thing," he adds. "I just hope it leads to more people reading about him and finding out the truth." Maybe major films are not the place for a perfectly accurate portrayal of science and scientists, says Kirby. Instead people should seek out other forms of media, like the recent LabLit movement, which is dedicated to the depiction of real laboratory culture in fictional media, or indie art house films. But van Wyhe says he would rather see Hollywood sell their films as the true story of historical figures in science and then live up to that commitment – because, after all, aren't the accomplishments of these famous researchers interesting enough? In the words of Jules Verne, the influential French science fiction writer, "reality provides us with facts so romantic that imagination itself could add nothing to them." Photo credit: Black Bear Pictures Read this post online: http://www.euroscientist.com/work-life-balance/ EuroScience | 1, Quai Lezay-Marnésia | F-67000 Strasbourg | France Tel +33 3 8824 1150 | Fax +33 3 8824 7556 | [email protected] | www.euroscience.org

© Copyright 2026