Economist Insights Space saving

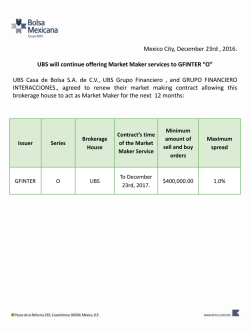

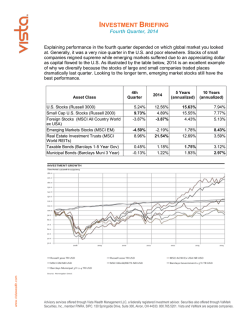

Asset management 2 February 2015 Economist Insights Space saving Low interest rates mean that governments’ borrowing costs have fallen, so they are making implied savings simply from not having to pay as much in interest payments. The low rates may be due to the dominance of priceinsensitive buyers of government bonds. With the ECB embarking on its QE programme, if there are limited sellers of government bonds then bond yields could fall by more than is currently priced in. Joshua McCallum Head of Fixed Income Economics UBS Global Asset Management [email protected] Gianluca Moretti Fixed Income Economist UBS Global Asset Management [email protected] The recent bond rally has been great for anyone who holds government bonds. But it has also been great for anyone who wants to sell government bonds. And the biggest sellers of government bonds are the governments themselves. The central banks can be thanked for this bonanza due to their programmes of quantitative easing (QE). Some economists refer to QE as ‘quasi-fiscal’ policy because of the fiscal benefits it brings to governments. Italy in particular is a big beneficiary, with interest savings of over 0.6% of GDP. This is a lot compared to Italy’s planned fiscal tightening of about 1% of GDP. So Italy has arguably achieved more than half of its planned fiscal tightening simply because borrowing costs have fallen. The lower interest payments give Italy ‘fiscal space’ which it can use to either cut debt faster, or reduce the amount of austerity. The benefits from lower interest rates can be measured by looking at how much higher the interest payments for government debt would be if interest rates had not changed over the last year. The lower interest rate will not affect all government debt, only debt that is rolled over into new bonds or is newly issued to cover the ongoing deficit. But that can still be a pretty substantial amount (chart 1). In other countries the benefits are not so large, but Spain will still find its life noticeably easier as a result. The benefits to countries such as Germany and France are far less because they are issuing less debt. It is also less important to them because they are not planning any fiscal consolidation this year. Chart 1: Fiscal space Planned fiscal consolidation in 2015 and implied savings from lower interest rates, % of GDP 1.5 1.2 0.9 Outside the Eurozone interest rates are also low. The US is undertaking a fiscal tightening so lower interest payments would be welcome. But the US Treasury still insists on issuing most of its debt with quite short maturities, where the shift in the interest rates curve has been much smaller. Although the UK has traditionally issued longer-dated debt, last year much of the debt it issued was of much shorter maturity. Given the size of fiscal tightening planned in the UK for this year, maybe the UK government should think about issuing more longer-dated bonds. 0.6 0.3 0.0 -0.3 Germany France Fiscal consolidation Italy Spain Interest rate saving US UK Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P., IMF, UBS Global Asset Management. Note: interest rate savings are calculated by taking gross issuance in 2015 and assuming the same maturity distribution as 2014, then applying the change in borrowing costs over the last 12 months. The calculations also assume that the interest rate for each maturity remains unchanged at the level of the end of January. However, this interest rate saving is only the indirect effect of QE. There is a more direct effect that will benefit governments. Because of the way QE is designed in the Eurozone, the national central bank balance sheets will take the majority of the exposure to potential losses on the bonds they purchase. However, this means that they will be keeping most of the coupon payments they make on their bonds. If, as happens with the Securities Markets Programme, those coupon payments are returned to the government, then the saving of public finances could be at least an additional 0.3-0.4% of GDP in countries like Italy and Spain. Who will sell? The government bond market is not a normal market, at least not anymore. In most securities markets, investors buy the securities because they like the expected return relative to the expected risk. Yet there are many buyers of government bonds who do not care about the returns. A foreign central bank that wants to hold EUR-denominated foreign exchange reserves buys government bonds because they are safer than other assets and are in the right currency. The returns are a secondary consideration. Regulations require banks to hold a lot of government bonds as part of their capital; the banks have no choice so the return is not even considered. Pension funds and insurance companies have to ensure that their assets match their liabilities, and with many long-term liabilities they must buy the only source of long-term ‘safe’ assets around: government bonds. Chart 2: Insensitive Holders of Eurozone government bonds, Q3 2014 Foreign 31% Banks 30% Pension & insurance 20% Investment funds 11% Others 6% ECB 2% For the sake of argument, assume that about half of the foreign holdings of Eurozone government bonds are with foreign central banks (based on IMF data on declared currency reserves). Assume also that banks and pension funds are unwilling to sell their government bonds. That leaves only about a third of Eurozone government bonds held by willing sellers. This is quite a challenge when the ECB is planning to buy over a third of that remaining amount. In line with the European Court of Justice opinion on the Securities Markets Programme, the ECB is keen to avoid distorting the markets so it has limited its purchases of any single issuance. But the effective, or liquid, market might be so small that distortions are inevitable. When there are fewer sellers relative to the amount being bought, prices should rise. Unless the price-insensitive buyers turn out to be more willing to sell (for example, banks might have more government bonds than they need), this really suggests that bond prices should rise (yields should fall). The market may already have spotted this mismatch, which would help explain why Eurozone bond yields continue to fall despite the uncertainties about Greece. Or the ECB may find that it ends up paying over the odds for increasingly scarce government bonds. Governments in the Eurozone may be benefiting from extra fiscal space thanks to the ECB’s QE programme, but the ECB itself may find it has very limited space within which to conduct its QE programme. But at least the ECB can be reassured that the less space it has (and the lower it pushes bond yields), the more space it creates for the governments. Source: ECB Monthly Bulletin, UBS Global Asset Management The common theme is that all of these buyers are price-insensitive. The majority of the government bonds they hold would have been bought even if the yield were zero (or even negative). Now the ECB is embarking on QE and is planning to buy about 12% of the Eurozone government bond market over the next 18 months. But who will want to sell the bonds to them (chart 2)? Foreign central banks want to keep their reserves. The banks need to meet regulatory requirements. Pension and insurance funds need to match their liabilities. That leaves investment funds, foreign non-central bank holders and the ‘others’ (households and non-financial corporations) who may be willing to sell their government bonds. The views expressed are as of February 2015 and are a general guide to the views of UBS Global Asset Management. This document does not replace portfolio and fund-specific materials. Commentary is at a macro or strategy level and is not with reference to any registered or other mutual fund. This document is intended for limited distribution to the clients and associates of UBS Global Asset Management. Use or distribution by any other person is prohibited. Copying any part of this publication without the written permission of UBS Global Asset Management is prohibited. Care has been taken to ensure the accuracy of its content but no responsibility is accepted for any errors or omissions herein. Please note that past performance is not a guide to the future. Potential for profit is accompanied by the possibility of loss. The value of investments and the income from them may go down as well as up and investors may not get back the original amount invested. This document is a marketing communication. Any market or investment views expressed are not intended to be investment research. The document has not been prepared in line with the requirements of any jurisdiction designed to promote the independence of investment research and is not subject to any prohibition on dealing ahead of the dissemination of investment research. The information contained in this document does not constitute a distribution, nor should it be considered a recommendation to purchase or sell any particular security or fund. The information and opinions contained in this document have been compiled or arrived at based upon information obtained from sources believed to be reliable and in good faith. All such information and opinions are subject to change without notice. A number of the comments in this document are based on current expectations and are considered “forward-looking statements”. Actual future results, however, may prove to be different from expectations. The opinions expressed are a reflection of UBS Global Asset Management’s best judgment at the time this document is compiled and any obligation to update or alter forward-looking statements as a result of new information, future events, or otherwise is disclaimed. Furthermore, these views are not intended to predict or guarantee the future performance of any individual security, asset class, markets generally, nor are they intended to predict the future performance of any UBS Global Asset Management account, portfolio or fund. © UBS 2015. The key symbol and UBS are among the registered and unregistered trademarks of UBS. All rights reserved. 24241

© Copyright 2026