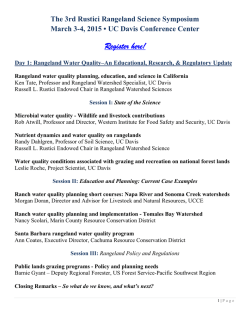

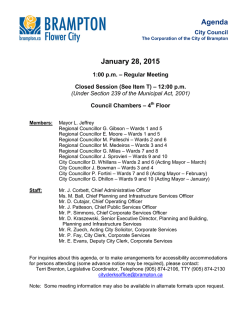

Here - Roizen