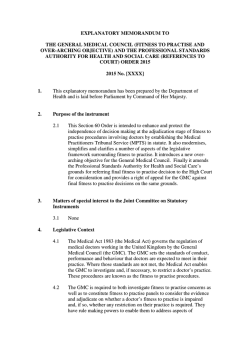

Government response to the Law Commission report