Favorable Prognosis of Hyperdiploid Common

From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on February 6, 2015. For personal use only.

Favorable Prognosis of Hyperdiploid Common Acute Lymphoblastic

Leukemia May Be Explained by Sensitivity to Antimetabolites

and Other Drugs: Results of an In Vitro Study

By G.J.L. Kaspers, L.A. Smets, R. Pieters, C H . Van Zantwijk, E.R. Van Wering, and A.J.P. Veerman

DNA hyperdiploidy is a favorable prognostic factor in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). The explanation

for this prognostic significance islargely unknown. Wehave

studied whether DNA ploidy was related to cellular resistance to 12 drugs, assessed with themethyl-thiazol-tetrazolium assay, in samples of 74 children with common (CD10'

precursor B-cell)ALL. Sixteen patients had hyperdiploid ALL

cells and 58 patients hadnonhyperdiploid ALL cells. Hyperdiploid ALLcells were more sensitive to mercaptopurine

(median, 9.0-fold; P = .000003),to thioguanine (1.4-fold; P =

.023),to cytarabine (1.8-fold; P = .016), and to l-asparaginase

(19.5-fold; P = .022) than werenonhyperdiploid ALL cells. In

contrast, these two ploidy groups did notdiffer significantly

in resistance to prednisolone, dexamethasone, vincristine,

vindesine,daunorubicin,doxorubicin,

mitoxantrone, and

teniposide. The percentage of S-phase cells was higher ( P

= .05) in the hyperdiploid ALL samples (median, 8.5%) than

in the nonhyperdiploid ALL samples (median, 5.7%). However, the percentage of cellsin S-phase was notsignificantly

related to in vitro drug resistance. We conclude that the

favorable prognosis associated with DNA hyperdiploidy in

childhood common ALL may be explained by a relative sensitivity of hyperdiploid common ALL cells to antimetabolites,

especially to mercaptopurine and to l-asparaginase.

0 1995 by The American Societyof Hemstology.

T

sala, Sweden) for 15 minutes (room temperature, 1,OOOg). Immunofluorescence techniques were used for terminal deoxynucleotidyl

transferase (TdT) and cytoplasmic and surface Ig M heavy chain

staining, whereas an indirect immunoperoxidase staining technique

on cytocentrifuge preparations was used for all other antibodie~.'~

A leukemia was considered to be a precursor-B common-ALL (cALL) if the malignant cells were positive for TdT, CDlO, CD19,

andHLA-DRand negative for cytoplasmic and/or surface Ig M

heavy chain.

Materials. Prednisolone sodium phosphate (PRD), dexamethasone sodium phosphate (DXM), daunorubicin hydrochloride (DNR),

l-asparaginase (ASP), cytarabine (ARA-C), vindesine sulphate

(VDS), vincristine sulphate (VCR), mitozantrone hydrochloride

(MIT), teniposide (TEN), and acidified (0.04 N HCl) isopropanol

were obtained from the hospital pharmacy. Thioguanine (6TG), mercaptopurine (6MP), and doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX) were obtained from Sigma Chemical CO (St Louis, MO).

PRD was dissolved in saline. DNR, ASP, VDS, and DOX were

dissolved in distilled water. 6MP and 6TG were dissolved in 0.1 N

NaOH. DXM, ARA-C, VCR, MIT, and TEN were obtained in soluble form.

Cells were cultured in suspension inRPM1 1640 (GIBCO, Uxbridge, UK) containing fetal calf serum (Flow Laboratories, Irvine,

UK) and supplements as described previously.i6 MTT (3-[4,5dimethyl-thiazol-2-yI]-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium-bromide)

was obtained from Sigma.

Drug resistance assay. The MTT assay was performed at the

research laboratory for pediatric hemato-onco-immunology ofthe

HE IDENTIFICATION OF prognostic factors in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has allowed

the use of risk-group stratification and subsequent risk-group

adapted treatment. This approach is likely to have contributed to the marked improvement in the prognosis of this

disease in children.' DNA ploidy, as determined by karyotyping or flow cytometric measurement of DNA content,

has strong and independent prognostic Significance.' DNA

hyperdiploidy is especially associated with a favorable prognosis in B-lineage

The explanation for the good

prognosis associated with DNA hyperdiploidy in B-lineage

ALL is unknown. However, Whitehead et a l l ' recently reported that DNA hyperdiploid ALL cells accumulated higher

levels of methotrexate polyglutamates than did other aneuploid and diploid ALL cells, which suggests that DNA hyperdiploid ALL cells are more sensitive to methotrexate.

We studied the relationship between DNA ploidy, percentage of cells in S-phase, and cellular resistance to 12 drugs

assessed using the methyl-thiazol-tetrazolium (Mm)assay

in 74 samples of children with newly diagnosed common

ALL. The MTT assay is an objective and reliable cell culture

drug-resistance assay, suited for large-scale testing of leukemia and lymphoma samples." Using this assay, we showed

that in vitro resistance to certain drugs is related to the clinical outcome in childhood ALL.13

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients. Bone marrow or peripheral blood samples were sent

by local institutions to the Dutch Childhood Leukemia Study Group

laboratory for confirmation of the new diagnosis ALL by classification according to the criteria of the French-American-British (FAB)

groupi4and imm~nophenotyping.'~

Samples of 88 children with nonB ALL were sent by the Dutch Childhood Leukemia Study Group

laboratory to the research laboratory for pediatric hemato-onco-immunology of the Free University Hospital for cellular drug resistance

testing and to the Department of Experimental Therapy of the Netherlands Cancer Institute for DNA ploidy and percentage of S-phase

cells measurements. Informed consent was obtained. Cellular drug

resistance and DNA ploidy assays were successfully performed in

74 patients. Table 1 summarizes the clinical and cell biologic features

of these patients.

Cells. Mononuclear cells were isolated by Ficoll density gradient

centrifugation (Ficol Paque; density, 1.077 g/mL; Pharmacia, UppBlood, Vol 85, No 3 (February l ) , 1995: pp 751-756

Fromthe Department of Pediatrics, Free University Hospital,

Amsterdam; the Department of Experimental Therapy, The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam; and the Dutch Childhood Leukemia Study Group, The Hague, The Netherlands.

Submitted September 13, 1994; accepted September 27, 1994.

Supported by the Dutch Cancer Society ( I K A 89-06) and by the

project VONK (VU Onderzoek Naar Kinderkanker).

Address reprint requests to G.J.L. Kaspers, MD, PhD, Department

of Pediatrics, Free University Hospital, De Boelelaan 1117, l081

HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page

charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked

"advertisement" in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734 solely to

indicate this fact.

0 1995 by The American Society of Hematology.

0006-4971/95/8503-0117$3.00/0

751

From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on February 6, 2015. For personal use only.

752

KASPERS ET AL

Table 1. Features of 74 Children With Newly Diagnosed c-ALL

DNA Ploidy

Nonhyperdiploid

No. of patients

58

Malefiemale ratio

27/31

Median

age

in

mo (range)

54 (3-190)

Median WBC x109/L

25.5 (3.6-729) 39.2

(range)(2.5-149.4)

FAB type

L1

47

L2

11

Median percentage of cells

in S-phase (range)

(4.2-20)

(0.2-30)

8.5

5.7

Hyperdiploid

16

1214

(17-190)

44

14

2

thusattemptedtoexcludenear-triploidandnear-tetraploidcases

(with a DNA index of > 1.35) from the hyperdiploid group,because

these patients have a less favorable prognosis? The percentage of

S-phase cells was determined by planimetry of DNA cell readings,

and was expressed as a percentage of all cells, irrespective of DNA

content.

Statistics. Computer equipment was provided by Olivetti NederlandBV (Leiden, The Netherlands). The Wilcoxon's ranking test

for unpaired data and thex' test were used for two-tailed testing at

a level of significance of .05. The Spearman's rank correlation test

(parameterp ) was used to study the relation between the percentage

of S-phase cells and LC50 values.

RESULTS

Sixteen (22%) of the 74 patients had hyperdiploid ALL

cells and 58 patients had nonhyperdiploid ALL cells. Patient

Free University Hospital within 36 hours after collection of the bone characteristics of the two groupsare shown in Table1. These

characteristics did not differsignificantly, except that hypermarrow or peripheral blood sample. Samples from these sources do

not differ in drug resistance and were therefore evaluated together." diploidy was more frequentin male patients ( P = .M).HowAll samples tested with the MlT assay contained 280% leukemic

ever, for 14 nonevaluable cases, the white blood cell counts

in case of doubt,

cells after isolation (assessed morphologically and,

( M C ) of the 9 hyperdiploid cases were lower (median, 6.2

also immunologically), which has proven to give reliable test reX 109/L; range, 3.2 to 41.9 X 109/L) than those of the 5

s u l t ~ . 'In

~ allsamples,thecellviability,assessed

by trypanblue

nonhyperdiploid cases (median, 23.8 X 109/L; range, 4.8 to

exclusion, was 295% at the start of the culture.

89.3 X 109/L). Patient characteristics other then WBC did

Eighty microliters ofcell suspension (2X lo6cells/mL)was added

not differ between the ploidy groups in these nonevaluable

to 20pL of the various drugsolutions in 96-well microculture plates.

cases. The MTT assay results of these 14 samples were not

Each drug was tested in 6 concentrations in duplicate, with concenevaluable because of an optical density of less than 0.050

tration ranges as reported previously.'6 These concentrationsdo not

(n = 7) or because of less than 70% of leukemic cells in the

necessarily stay the same during the 4 days of incubation. Expericontrol wells (n = 7). The failure rate was thus significantly

ments (not shown here) showed no differences between 6MP and

to the

( P = ,001)higherin hyperdiploid c-ALLsamples (9/25)

6TG regarding their in vitro behavior (stability and adherence

walls of the plates). Wells with culture medium only (for 6MP and than in nonhyperdiploid c-ALL samples

(5/63). In agreement

6TGwith drug) were used to blank the reader, and

6 wells with

with this observation, we found thatthe control cell survival

cells in medium without drugs were used to determine the control

in the successfully tested samples was lower ( P = .003) in

cell survival and to calculate the coefficient of variation of control

hyperdiploid samples (median, 46%; range, 26% to 69%)

wells. The plates were incubated in humidified air containing

5%

than in nonhyperdiploid samples (median, 68%; range, 23%

CO2 for 4 days at 37°C. Then, 10 pL of MTT solution (5 mg/mL)

was added to the plates. After shaking the plates until the cell pellet to 135%).Similarly, the percentage of leukemiccells in

control wells after 4 days of culture was lower ( P = .005)

was resuspended, they were incubated for 6 hours. The tetrazolium

in hyperdiploid samples (median, 80%; range, 71% to 95%)

salt MTT is reduced to a colored formazan by living cells but not

than in nonhyperdiploid samples (median, 92%; range,71%

by dead cells. The formazan crystals formed were dissolved with

100 pL acidified isopropanol. The optical density of the wells, which to 99%). At the start of culture, these median percentages

is linearily related to the cell number," was measured with an ELwere both 94%.

312 microplate spectrophotometer (Bio-tek Instruments Inc. WinooThe hyperdiploid and nonhyperdiploidc-ALL samples

ski, VT) at 562 nm. Leukemic cell survival (LCS) was calculated

showed a large overlap of individual LC50 values for all

by the equation: LCS = (mean optical density treated wellslmean

drugs, except for 6MP. Hyperdiploid c-ALL samples were

optical density control wells) X 100%. The LC50, the drug concensignificantly more sensitive to 6MP (median, 9.0-fold; P =

tration lethal to 50% ofthe cells, wascalculatedfromthedose.00OOO3), to 6TG (1.4-fold; P = .023), to ARA-C (1.8-fold;

responsecurveandusedasmeasure

of resistance.Resultswere

P

= .016), and to ASP

(19.5-fold; P = .022) thanwere

considered evaluable in case of an optical density of

20.050 and

nonhyperdiploid c-ALL samples. Figure 1 shows these dif270% leukemic cells in the control wells (leukemic cells without

ferences for individual patients. In addition to these signifidrug), which assures reliable test result^.'"'^

cant differences, hyperdiploid c-ALL samples were not sigThe intra-assay (duplicates) and inter-assay (repeated testing

of a

frozen sample) variation in LC50 values is less than 1 dilution step

nificantly moresensitivetothe

structurallyrelated drugs

for each drug. The median coefficient

of variationofthecontrol

PRD (6.3-fold) andDXM (8.6-fold). Fortheremaining

wells was 5.2% (range, 0.9% to 15.3%).

drugs, small and nonsignificant differences were observed

DNA ploidy and S-phase deferminafion. Flow cytometric analy(Table 2). In some samples, not all drugs could be tested

sis of cellular DNA content and cell cycle distribution was performed because of the lack of material. However, 6MP and 6TG

withanimpulsecytophotometer

(ICP-11; Phywe AG, Gottingen,

were successfully tested in the same specimens. Moreover,

Germany)onethidiumbromide-stained

cells asdescribedprean analysis including only those samples in which all three

viously.* The DNA index was definedas the modal DNA content of

antimetabolites (6MP,6TG,andARA)were

successfully

leukemic cells compared with

that of reference normal lymphocytes.

tested gave results very similar to those shown in Table 2

Patientsweredividedinhyperdiploid(DNAindex,

2 1.16and

(data not shown).

c 1.35) and nonhyperdiploid (DNA index,

t1.16 or > l .35). We

From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on February 6, 2015. For personal use only.

DNAPLOIDYANDDRUG

A

753

RESISTANCE IN CHILDHOODALL

po.oooooa

t

=E

P

p.o.02

P

00

0"

l00

0

10

S

u-

t

C

DIPLOID

D

p-0.04

k

0

NON-HYPER

DIPLOID

DIPLOID

HYPER

NON-HYPER

DlpLOlD

0

8

0

HYPER

jP0.04

n

1

v

0

16

Y

0.01

1

W

O

+

i

P

8

00

Qx)

0.00 l

"

1

NON-HYPER

DIPLOID

HYPER

DIPLOID

N01J-HWER

DIPLOID

0

HYPER

DIPLOD

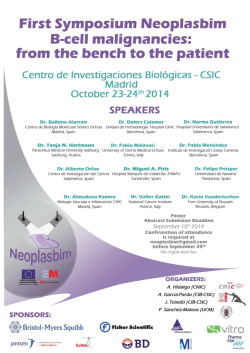

Fig l. Relationship betweenDNA ploidy determined byflow cytometry and cellular drug resistance determinedwith the colorimetric MlT

assay in childhood c-ALL. Cases were classified as hyperdiploid [DNAindex, 1.16 to 1.35) or nonhyperdiploid (DNAindex, <1.16 or >1.35). {A)

Mercaptopurine, (B) thioguanine, (C) cytarabine, and (D)L-asparaginase. (0)Individual and I+)median LC50 values.

The median percentage of S-phase cells was 8.5% in 13

hyperdiploid c-ALL samples (range, 4.2%to 20%)and 5.7%

(range, 0.2% to 30%)in the nonhyperdiploid c-ALL samples

( P = .OS; Fig 2). There was no significant correlation (all P

values >.20) between the percentage of S-phase cells and

LC50 values for PRD ( p .M), DXM ( p -.M), VCR ( p .15),

VDS ( p -.03), DNR ( p -.Ol), DOX ( p .12), MIT ( p .20),

TEN ( p .OS), ASP ( p -.lo), 6TG ( p -.05), and ARA-C ( p

- .06). Only for 6MP was a statistically borderline significant

correlation observed ( p -.30;P = .OS).

DISCUSSION

DNA hyperdiploidy is strongly and independently associated with a good prognosis in childhood ALL."" The reason

for this prognostic significance is largely unknown, but it

may be related to differences in cellular drug resistance.

Cellular drug resistance is one of the main determinants of

the clinical outcome after chemotherapy, together with the

pharmacokinetics of the administered drugsz0and with the

regrowth or relapse potential of minimal residual cells.21

Recently, Whitehead et all' reported that lymphoblasts of 13

children with hyperdiploid ALL accumulated higher levels

of methotrexate polyglutamates (MTXPG) than those in Blineage lymphoblasts of 34 children with other ploidy. The

investigators suggested that these high levels may increase

the cytotoxicity of MTX. Previously, the same investigators

had reported that children with B-lineage ALL, whose

lymphoblasts accumulated high levels of MTXPG in vitro,

had a better prognosis than did children with lower levels."

Otherwise, PinkelZ3reported in 1987 already that hyperdiploid c-ALL had a high cure rate with methotrexate and mercaptopurine.

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first

to report on a direct relation between DNA ploidy and cellular drug resistance in childhood ALL. Resistance to 12 drugs,

commonly used in the treatment of this disease, was investi-

From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on February 6, 2015. For personal use only.

754

KASPERS ET AL

Table 2. Relationship Between DNA Ploidy Determined by Flow

Cytometry and Cellular Drug Resistance Determined

With the Colorimetric MlT Assay in Untreated Childhood c-ALL

LC50 Values (WglrnL,

ASP IU/rnL)

Drug

PRD

DXM

VCR

VDS

DNR

DOX

MIT

TEN

ASP

6MP

6TG

ARA-C

DNA Ploidy

Median

Range

N

PValues

Nonhyperdiploid

Hyperdiploid

Nonhyperdiploid

Hyperdiploid

Nonhyperdiploid

Hyperdiploid

Nonhyperdiploid

Hyperdiploid

Nonhyperdiploid

Hyperdiploid

Nonhyperdiploid

Hyperdiploid

Nonhyperdiploid

Hyperdiploid

Nonhyperdiploid

Hyperdiploid

Nonhyperdiploid

Hyperdiploid

Nonhyperdiploid

Hyperdiploid

Nonhyperdiploid

Hyperdiploid

Nonhyperdiploid

Hyperdiploid

2.20

0.35

0.25

0.03

1.48

0.72

2.59

1.56

0.12

0.13

0.39

0.33

0.06

0.05

0.32

0.25

0.39

0.02

216.7

24.2

7.7

5.7

0.51

0.29

0.05-1500

0.05-134

0.003-6

0.0002-6

0.05-50

0.09-38.3

0.05-50

0.05-37.8

0.003-1.3

0.002-1.1

0.10-1.33

0.06-1.28

0.001-1.0

0.001-1.0

0.12-3.34

0.14-3.09

0.002-10

0.002-0.8

15.6-500

15.6-42.8

1.6-50

2.2-11.0

0.07-2.5

0.03-2.5

51

15

47

12

53

13

40

8

52

11

41

11

42

12

41

12

48

12

47

12

47

12

45

14

.l7

.09

.63

.35

.32

.34

.65

21

,022

.000003

,023

,016

Cases were classified as hyperdiploid ifthe DNA index was 1.16 to

1.35 and as nonhyperdiploid if the DNA index was <1.16 or >1.35.

gated in samples of 74 children with newly diagnosed cALL. Hyperdiploidy is found mainly in this immunophenotypic subgro~p.~".".*~

An analysis stratified for immunophenotype is also indicated because immunophenotype itself is

related to cellular drug resistance in childhood ALL.26MTX

was not included in the panel because this drug shows no

dose-dependent cytotoxicity in ALL patient samples in nonclonogenic cell culture drug resistance assays. A possible

explanation for this is described el~ewhere.'~

Hyperdiploid

c-ALL samples were more sensitive to all antimetabolites

tested (6MP, 6TG, and A M - C ) than were nonhyperdiploid

c-ALL samples. Hyperdiploid samples were also more sensitive to ASP. Resistance to each of the 8 other drugs did not

differ significantly between both ploidy groups. However, it

should be noted, that a limited number of samples has been

tested, especially in the hyperdiploid group. Some of the

nonsignificant differences might be clinically relevant and

need confirmation in a larger study.

The reason for the relative sensitivity of hyperdiploid cALL cells to antimetabolites is unknown. It has been attributed to a higher percentage of S-phase cells in hyperdiploid

than in nonhyperdiploid ALL.4 In the present study, the percentages of S-phase cells in the hyperdiploid c-ALL samples

were higher than those in the nonhyperdiploid c-ALL samples. However, in a limited number of samples (up to 38),

there was no significant and strong relation between the

percentage of S-phase cells and in vitro resistance to any of

the drugs tested.

It has been suggested that hyperdiploid ALL cells are

more sensitive to glucocorticoids, because of their tendency

towards terminal differentiation.' Both in vitro and in vivo

sensitivity to glucocorticoids is associated with a favorable

prognosis.'"28,29We found indeed that hyperdiploid c-ALL

samples were more sensitive to PRD (median, 6-fold) and

DXM (median, 9-fold) than were nonhyperdiploid samples.

However, the differences were not statistically significant.

The difference in resistance to ASP was significant, with

hyperdiploid c-ALL cells being a median of 19.5-fold more

sensitive. It seems of interest to study whether there are

differences in asparagine synthetase betweenhyperdiploid

and nonhyperdiploid c-ALL cells.

Hyperdiploid c-ALL samples were a median of 9.0-fold

more sensitive to 6MP, but were only 1.4-fold moresensitive

to 6TGthan were nonhyperdiploid c-ALL samples. This

discrepancy between 6MP and 6TG, two closely related thiopurines, is interesting. Both drugs are intracellularly metabolized into thioguanine nucleotides, which are subsequently

incorporated inDNAandRNA.

However, the conversion

of 6MP requires two enzymes more than the conversion of

6TG, namely inosinate (IMP) dehydrogenase and guanosylate synthetase. The rate-limiting enzyme is IMP dehydrogenase." In addition, both 6TG and 6MP are catabolized by

thiopurine methyltransferase, but this enzyme has a higher

affinity for 6MP." It is tempting to speculate that hyperdiploid and nonhyperdiploid c-ALL cells differ in the activity

of one or more of these enzymes. The favorable prognostic

value of hyperdiploidy is associated with nonrandom numerical chromosome gains, including chromosomes 4, 6, 10,

and 2 1 .',32,3' The genes encoding for the enzymes involved

in the intracellular metabolism of antimetabolites may localize to these chromosomes. However. an extensive literature

p=O.06

ao

0

¶6

Q

0'

-0

NON-HDROID

HYPeR

DlPLolo

Fig 2. Percentages of S-phase cells in hyperdiiloidand nonhyperdiploid childhood c-ALL samples. (0)Percentage of S-phase cells; ( + l

median value.

From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on February 6, 2015. For personal use only.

DNA PLOIDY AND DRUGRESISTANCE IN CHILDHOOD ALL

search did not show the chromosomal locations of the enzymes mentioned above.

One concern in our study is that the success rate of the

MTT assay was lower in hyperdiploid samples. Moreover,

the control cell survival and the percentage of leukemic cells

after 4 days of culture were lower in successfully tested

hyperdiploid samples than in nonhyperdiploid samples. This

finding is in agreement with preliminary results presented

by Campana et al,34 who reported that hyperdiploid ALL

cells were more likely to die in vitro, via induction of

apoptosis. Thus, it may be that hyperdiploid c-ALL samples

are actually even more drug sensitive than are nonhyperdiploid c-ALL samples than our study shows, because leukemic

cells that die spontaneously (not drug-induced) by apoptosis

may also be relatively sensitive to the cytotoxicity of anticancer agents. Most anticancer agents appear to kill malignant

cells by a p o p t ~ s i s . ~ ~

We conclude that hyperdiploid c-ALL samples are more

sensitive to antimetabolites (especially to 6MP) and to ASP

than are nonhyperdiploid c-ALL samples. This difference

may contribute to the more favorable prognosis associated

with DNA hyperdiploidy. The observation of other investigators that hyperdiploid ALL cells, compared to ALL cells

of other ploidy, accumulate higher levels of MTXPG and

therefore are likely to be more sensitive to MTX supports

the general conclusion that the prognostic significance of

DNA ploidy in childhood ALL is most likely to be mainly

explained by its relation with antimetabolite resistance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Computer equipment was provided by Olivetti Nederland BV. The

laboratory of the Dutch Childhood Leukemia Study Group (DCLSG)

provided the patient samples. Board members of the DCLSG are H.

Van Den Berg, M.V.A. Bruin, J.P.M. Bokkerink, P.J. Van Dijken,

K. Hiihlen,W.A. Kamps, F.A.E. Nabben, A. Postma, J.A.Rammeloo, I.M. Risseeuw-Appel, A.Y.N. Schouten-Van Meeteren,

G.A.M. De Vaan, E. Th. Van’t Veer-Korthof, A.J.P. Veerman, M.

Van Weel-Sipman, and R.S. Weening.

REFERENCES

1. Hammond GD: Leukemia cell DNA content: Predictor of late

relapse in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 9:1332, 1991

2. Pui C-H, Crist WM, Look A T Biology and clinical significance of cytogenetic abnormalities in childhood acute lymphoblastic

leukemia. Blood 76:1449, 1990

3. Jackson JF, Boyett J, Pullen J, Brock B, Patterson R, Land V,

Borowitz M, Head D, Crist W: Favorable prognosis associated with

hyperdiploidy in children with acute lymphocytic leukemia correlates with extra chromosome 6. A Pediatric Oncology Group study.

Cancer 66:1183, 1990

4. Look AT, Roberson PK, Williams DL, Rivera G , Bowman

WP, Pui C-H, Ochs J, Abromowitch M, Kalwinsky D, Dahl GV,

George S , Murphy SB: Prognostic importance of blast cell DNA

content in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 65: 1079,

1985

5 . Pui C-H, Dodge RK, Look AT, George SL, Rivera GK, Abromowitch M, Ochs J, Evans WE, Crist WM, Simone JV: Risk of

adverse events in children completing treatment for acute lymphoblastic leukemia: St Jude Total Therapy Studies VIII, IX, and X. J

Clin Oncol 9:1341, 1991

6. Secker-Walker LM, Lawler SD, Hardisty RM: Prognostic im-

755

plications of choromosomal findings in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia at diagnosis. Br Med J 2:1529, 1978

7. Secker-Walker LM, Chessels JM, Stewart EL, Swansbury GJ,

Ricards A, Lawler SD: Chromosomes and other prognostic factors

in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: A long-term follow-up. Br J

Haematol 72:336, 1989

8. Smets LA, Homan-Blok, Hart A, De Vaan G , Behrendt H,

H&len K, De Waal FC: Prognostic implication of hyperdiploidy as

based on DNAflow cytometric measurement in childhood acute

lymphocytic leukemia-A multicenter study. Leukemia 1:163,1987

9. Trueworthy R, Shuster J, Look T, Crist W, Borowitz M, Carroll

A, Frankel L, Harris M, Wagner H, Haggard M, Mosijczuk A,

Steuber P, Land V: Ploidy of lymphoblasts is the strongest predictor

of treatment outcome in B-progenitor cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia of childhood: A Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol

10:606, 1992

10. Williams DL, Tsaiatis A, Brodeur GM, Look AT, Melvin

SL, Bowman WP, Kalwinsky DK, Rivera G, Dahl GV: Prognostic

importance of chromosome number in 136 untreated children with

acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 60:864,1982

11. Whitehead VM, Vuchich MJ, Lauer SJ, Mahoney D, Carroll

AJ, Shuster JJ, Esseltine DW, Payment C, Look AT,Akabutu J,

Bowen T, Taylor LD, Camitta B, Pullen DJ: Accumulation of high

levels of methotrexate polyglutamates in lymphoblasts from children

with hyperdiploid (>SO chromosomes) B-Lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A Pediatric Oncology Group study. Blood 801316,

1992

12. Veerman AJP, Pieters R: Drug sensitivity assays in leukaemia

and lymphoma. Br J Haematol 74:381, 1990

13. Pieters R, Huismans DR, Loonen AH, Hiihlen K, Van Der

Does-Van Den Berg A, Van Wering ER, Veerman AJP: Relation

of cellular drug resistance to long term clinical outcome in childhood

acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Lancet 338:399, 1991

14. Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, Flandrin G, Galton

DAG, Gralnick HR. Sultan C: The morphological classification of

acute lymphoblastic leukaemia: Concordance among observers and

clinical correlations. Br J Haematol 47:553, 1981

15. Van Wering ER, Brederoo P, Van Staalduinen GI. Van Der

Meulen J, Van Der Linden-Schrever BEM, Van Dongen JJM: Contribution of electron microscopy to the classification of minimally

differentiated acute leukemias in children. Recent Results Cancer

Res 131:77, 1993

16. Kaspers GJL, Pieters R, Van Zantwijk CH, De Laat PAJM,

De Waal FC, Van Wering ER, Veerman AJP In vitro drug sensitivity

of normal peripheral blood lymphocytes and childhood leukaemic

cells from bone marrow and peripheral blood. Br J Cancer 64:469,

1991

17. Pieters R, Huismans DR, Leyva A, Veerman AJP: Comparison of the rapid automated MTT-assay with a dye exclusion assay

for chemosensitivity testing in childhood leukemia. Br J Cancer

59:217, 1989

18. Pieters R, Huismans DR. Leyva A, Veerman AJP: Adaptation

of the rapid automated tetrazolium dye based MTT assay for chemosensitivity testing in childhood leukemia. Cancer Lett 41:323, 1988

19. Kaspers GJL, Veerman AJP, Pieters R, Broekema GJ, Huismans DR, Kazemier KM, Loonen AH, Rottier MAA, Van Zantwijk

CH, Hiihlen K, Van Wering ER: Mononuclear cells contaminating

acute lymphoblastic leukaemic samples tested for cellular drug resistance using the methyl-thiazol-tetrazolium assay. Br J Cancer 1994

(in press)

20. Evans WE, Petros W,Relling MV, Crom WR, Madden

T, Rodman JH, Sunderland M: Clinical pharmacology of cancer

chemotherapy in children. Pediatr Clin North Am 36: 1199, 1989

21. Preisler HD, Raza A, Larson R, Goldberg J, Tricot G, Carey

M, Kukla C: Some reasons for the lack of progress in the treatment

From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on February 6, 2015. For personal use only.

756

of acute myelogenous leukemia: A review of three consecutive trials

of the treatment of poor prognosis patients. Leuk Res 15:773, 1991

22. Whitehead VM, Rosenblatt DS, VuchichM-J, Shuster JJ,

Witte A, Beaulieu D: Accumulation of methotrexate and methotrexate polyglutamates in lymphoblasts at diagnosis of childhood acute

lymphoblastic leukemia: A pilot prognostic factor analysis. Blood

7644, 1990

23. Pinkel D:Curing children of leukemia. Cancer 59:1683, 1987

24. Look AT, Melvin SL, Williams DL, Brodeur GM, Dah1 GV,

Kalwinsky DK, Murphy SB, Mauer AM: Aneuploidy and percentage

of S-phase cells determined byflow cytometry correlate with cell

phenotype in childhood acute leukemia. Blood 60:959, 1982

25. Pui C-H, Williams DL, Roberson PK, Raimondi SC, Behm

FG, Lewis SH, Rivera GK, Kalwinsky DK, Abromowitch M, Crist

WM. Murphy SB: Correlation of karyotype and immunophenotype

in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 6:56, 1988

26. Pieters R, Kaspers GJL, Van Wering ER, Huismans DR,

Loonen AH, H2hlen K, Veerman AJP: Cellular drug resistance profiles that might explain the prognostic value of immunophenotype,

age and sex in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia

7:392, 1993

27. Pieters R, Loonen AH, Huismans DR, Broekema GJ, Dirven

MWJ, Heyenbrok MW, HMen K, Veerman AJP: In vitro sensitivity

of cells from children with leukemia using the MTT assay with

improved culture conditions. Blood 76:2327, 1990

28. Kaspers GJL, Pieters R, Van Zantwijk CH, Van Wering ER,

Van Der Does-Van Den Berg A, Veerman AJP: Resistance to prednisolone (PRD) in vitro: A new prognostic factor in childhood acute

KASPERS ET AL

lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) at initial diagnosis. Proc Am SOC

Clin Oncol 12:320, 1993 (abstr)

29. Riehm H, Reiter A, Schrappe M, Berthold F, Dopfer R, Gerein V, Ludwig R, Ritter J, Stollmann B, Heme G: Die CorticosteroidAbhangige Dezimierung der Leukamiezellzahl im Blut als Prognosefaktor bei der Akuten Lymphoblastischen Leukamie im

Kindesalter (Therapiestudie ALL-BFM 83). Klin Padiatr 199:151,

I986

30. Weber G: Biochemical strategy of cancer cells and the design

of chemotherapy: G.H.A. Clowes Memorial Lecture. Cancer Res

43:3466, 1983

3 1. Woodson LC, Weinshilboum RM: Human kidney thiopurine

methyltransferase purification and biochemical properties. Biochem

Pharmacol 32:819, 1983

32. Hams MB, Shuster JJ, Carroll A, Look AT, Borowitz MJ,

Crist WM, Nitschke R, Pullen J, Steuber CP, Land VJ: Trisomy of

leukemic cell chromosomes 4 and IO identifies children withBprogenitor cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia with a very low risk

of treatment failure: A Pediatric Oncology Group study. Blood

79:3316, 1992

33. Smets LA, Slater RM, Behrendt H, Van 'T Veer MB, HomanBlok J: Phenotypic and karyotypic properties of hyperdiploid acute

lymphoblastic leukaemia of childhood. Br J Haematol 61:l 13, 1985

34. Campana D, Kumagai M, Manabe A, Murti KG, Behm FG,

Mahmoud H, Raimondi SC: Hyperdiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL): A distinct biological entity with marked propensity

to programmed cell death. Blood 82:49a, 1993 (abstr, suppl I )

35. Hickman JA: Apoptosis induced by anticancer drugs. Cancer

Metastasis Rev 1 l:121, 1992

From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on February 6, 2015. For personal use only.

1995 85: 751-756

Favorable prognosis of hyperdiploid common acute lymphoblastic

leukemia may be explained by sensitivity to antimetabolites and other

drugs: results of an in vitro study

GJ Kaspers, LA Smets, R Pieters, CH Van Zantwijk, ER Van Wering and AJ Veerman

Updated information and services can be found at:

http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/85/3/751.full.html

Articles on similar topics can be found in the following Blood collections

Information about reproducing this article in parts or in its entirety may be found online at:

http://www.bloodjournal.org/site/misc/rights.xhtml#repub_requests

Information about ordering reprints may be found online at:

http://www.bloodjournal.org/site/misc/rights.xhtml#reprints

Information about subscriptions and ASH membership may be found online at:

http://www.bloodjournal.org/site/subscriptions/index.xhtml

Blood (print ISSN 0006-4971, online ISSN 1528-0020), is published weekly by the American

Society of Hematology, 2021 L St, NW, Suite 900, Washington DC 20036.

Copyright 2011 by The American Society of Hematology; all rights reserved.

© Copyright 2026