Hot Topics - Latin American Research Centre

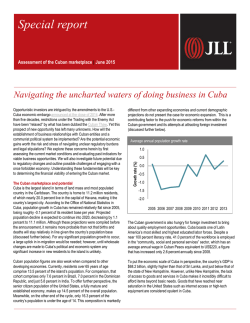

Hot Topics An exploration of current events and controversial topics in Latin America. Towards a Normalization of Cuba-United States Relations After more than fifty years of hostility, history was made on December 17, 2014 when Presidents Barack Obama and Raúl Castro agreed to move towards restoring diplomatic relations with each other. On the following January 21 and 22, follow-up meetings took place in Havana between Roberta Jacobson, Assistant Secretary of State for the Western Hemisphere, and Josefina Vidal, head of the U.S. Section of Cuba’s Ministry of Foreign Relations. The objective was to discuss details of the agreement reached by both presidents on working towards a normalization of bilateral relations. These matters are complicated, but will have to be resolved before the thorny issue of the embargo can be discussed. It will prove to be a long and challenging process. The Presidents’ Agreement December 17, 2014) The ground-breaking agreement is ambitious, with both sides seeking to protect their ideological territory, and explain their interpretation of several fundamental issues, such as their different interpretations of democracy and human rights—without offending the other. It had taken a tremendous effort to reach this stage (7 meetings in Canada, culminating in a secret Vatican discussion) and so it was important for both parties not to isolate the other. Both realized that there were significant gains to be made from a re-establishment of relations—and too that there were tremendous hurdles to cross first. There are several straightforward issues to the agreement that were reached: proper embassies and ambassadors are to replace the “Special Interests sections” and their “directors” that currently exist, while diplomatic personnel are to have freedom of movement, and to import goods for official purposes. There was also an exchange of political prisoners: Alan Gross, who had been working on an illegal USAID-funded communications project, an unidentified Cuban spy who had been working for Washington, and the three remaining “counter-terrorists” who had spent over 15 years in U.S. prisons, were all released. These represent important concessions by both parties. There was also general agreement about the need to strengthen bilat- A Latin American Research Centre publication February 2015 By John M. Kirk John Kirk is Professor of Latin American Studies at Dalhousie University. His research focuses mainly on contemporary Cuba, and he is the author/coeditor of 14 books dealing with foreign relations, political history and culture of Cuba. The most recent are A Contemporary Cuba Reader: The Revolution under Raúl Castro (2015), Fighting Words: Competing Voices from Revolutionary Cuba (2009), Cuban Medical International: Origins, Evolution and Goals (2009), and Healthcare without Borders: Understanding Cuban Medical Internationalism (due out in July). He is the editor of the Contemporary Cuba series of the University Press of Florida, and a member of the editorial board of the International Journal of Cuban Studies, and Estudios del Desarrollo Social: Cuba y América Latina. Page 2 Josefina Vidal, Head of the U.S. Section of Cuba’s Ministry of Foreign Relations. Photo: miamiherald.com. eral agreements on migration, counter-narcotics operations, environmental protection and human trafficking policies. More significant was the interest in encouraging people-to-people exchanges, although Obama did not lift the prohibition on U.S. citizens traveling to Cuba. Travel restrictions were, however, made more flexible for the 12 approved categories under which U.S. citizens are allowed to visit Cuba (education, journalism, cultural exchange, etc.) on general licences, instead of seeking specific approval for each case. Travel agencies were also allowed now to operate with general licences, and U.S. tourists were to be able to bring in Cuban goods to the value of $400. Obama made clear that he was particularly keen to promote the growth of small, independent businesses, and to support the nascent private sector. He therefore sought to provide “alternative sources of information and opportunities for self-employment and private property ownership, and by strengthening independent civil society”. (1) Remittance limits were increased fourfold (to $2,000 per quarter), allowing CubanAmericans to support the entrepreneurial activities of selfemployed relatives. A list of goods that could be exported to the private sector was to be published (significant because the current embargo prohibits this at present). The objective, according to Obama, was to help Cubans “gain greater economic independence from the state” (p.4). The Cuban response was best articulated in a speech given by Raúl Castro on December 20. He repeated the longstanding interest of Cuba to work towards the normalization of relations, but reminded Obama that “every state has the inalienable right to choose their own political, economic, social and cultural form of government, without the interference in any way of another state”. (2) Clearly aware of Obama’s interest in bringing about significant political change in Cuba, he stated his objections, clearly and unequivocally. He also noted that Cuba had “firm convictions and many con- A Latin American Research Centre publication cerns about events in the United States in terms of the system of democracy as well as the human rights situation” but would not interfere in internal U.S. matters. The message was clear: revolutionary Cuba was adamant about protecting its socialist system, and rejected any U.S. intents at changing it. Clearly, while both presidents sought to forge a diplomatic agreement, they were far apart on some fundamental aspects. The Goals of the Meetings in Havana (January 21-22, 2015) Two days were spent in negotiations, the first on migration issues, and the second on the question of re-establishing diplomatic relations. U.S. media coverage was extensive, and in general extremely superficial. Expectations that “normalization” could occur swiftly were almost universally naïve, and were quickly dashed, since both sides had radically different interpretations of how they should proceed, what the goals were, and how these could be reached. There was a fundamental difference of opinion over several key issues. The U.S. position insisted that Cuba relax political control, allow greater freedom of expression, and show more respect for human rights. Cuba saw these demands as an unacceptable infringement on their sovereignty, and indeed unjustifiable meddling. Raúl Castro explained Cuba’s position clearly. Both countries should expect to maintain their own political system, regardless of ideological differences with the other: “Just as we Page 3 have never proposed that the United States should change their political system, so too we demand respect for our own”. Related to this major issue were several other key questions. The issue of compensation for the almost 6,000 American citizens and companies who had their properties expropriated is among them. The claims, adjusted for inflation, amount to some $7 billion. In contrast Cuba is claiming reparation for the 3,400 lives lost as a result of terrorist activities stemming from the United States (many sanctioned by various administrations that sought to topple the revolutionary government). In addition, Cuba claims that the embargo has resulted in Cuba spending an extra $1.1 trillion. Several other key irritants were discussed. Washington defended the Cuba Adjustment Act of 1966, which allows Cubans to reside legally in the United States as soon as they touch American soil. It is applied solely to Cubans. This policy (known as “wet footdry foot”) is rejected by Havana, which sees it as encouraging illegal (and dangerous) emigration. If there are “normal” bilateral relations, they argue, why can Cubans not just travel between both countries? After all, since January 2013 Cubans have been free to travel outside the country for up to two years (while ironically most Americans are denied that right by Washington). duced by the George W. Bush administration. The objective is to encourage Cuban medical personnel serving abroad in developing countries to defect, thus decreasing the international respect for Cuba’s medical internationalism programme. Havana objects to this, noting that this results in taking medical services away from those who need it most in poor, developing countries. Washington refused to drop the programme. Washington also keeps Cuba on the list of countries (along with Iran, Sudan and Syria) that allegedly sponsor terrorism, much to Havana’s frustration. Clearly there is a lack of logic in moving towards normalization of bilateral relations if Cuba is sponsoring terrorism. This policy can be overturned by presidential fiat, and most likely Cuba will be removed from the list in the coming months. Secretary of State John Kerry has been asked to investigate this situation, and indeed has offered to travel to Cuba when diplomatic relations are renewed. Another key issue not discussed was the situation of Guantánamo. Obama had promised to close down the detention centre early in his first mandate, and re- This policy of exceptionalism towards Cuban citizens is also seen in the Cuban Medical Professional Parole programme, introA Latin American Research Centre publication mains keen to do so. Meanwhile Cuba would like the entire U.S. military base (on 45 square miles of Cuban territory), occupied at the beginning of the 20th century, to be returned. There are clearly many key areas that need to be addressed before the re-establishment of diplomatic relations. The “normalization” of relations will come much later, and before that occurs, the very problematic issue of the embargo has to be resolved. That can only take place following an agreement to do so by the Republican-controlled Congress, where presidential hopefuls such as Ted Cruz, Marco Rubio and Jeb Bush have all expressed outspoken opposition to Obama’s approach to Cuba. The most recent polls show that 60-63% of Americans favour the re-establishment of relations with Cuba, as do most CubanAmericans. Likewise, scores of U.S. businesses have expressed their interest in exporting to and investing in the island, a position strongly favoured by Thomas Donohue, President of the U.S. Chamber of Commerce. The commercial interests are wide-ranging, Photo: bbc.co.uk. Page 4 from hotel chains to farming equipment manufacturers, airlines to communications technology companies, and all have urged Congress to support Obama’s initiative. It will be interesting to see whether the business lobby and American citizens (3 million of whom have expressed an interest in visiting Cuba once U.S. law permits this) manage to influence the Senate, and overturn the recalcitrant views of some senators. The Significance of the Meetings While there are many major challenges that need to be overcome, the meetings that took place in January of 2015 were nevertheless extremely important. Particularly significant was the symbolism of the occasion, since Roberta Jacobson was the highest-ranking U.S. official to visit Cuba in over 30 years. So, what was achieved? In terms of specific agreements or decisions, not much—apart from agreeing to meet again for further discussions. Some progress was made on migration matters, on areas of mutual cooperation (such as disaster relief and cultural exchanges, migration and tourism). What is important is that an attempt was made to introduce some significant confidencebuilding measures. The atmosphere for the discussions was cordial, respectful, and friendly. Both sides aired profoundly-rooted differences of opinion, but did so in a careful, non-threatening manner. There appears to be a genuine interest in reaching an agreement. Finally, both are aware that, as President Obama noted, “We cannot keep doing the same thing and expect a different result”. (3) Political will was shown by both Cuba and the United States to meet and work towards a peaceful solution following five decades of mutual recrimination and hostility, in itself a major breakthrough. Both sides are now well aware of the positions of the other, and there may well be further progress before Raúl Castro and Barack Obama meet at the Cumbre de las Américas in Panama, in April 2015. This will be a process fraught with difficulties, weighed down by five decades of mutual recrimination and hostility. That said, if both sides have the political will to make concessions, and can agree to disagree over fundamental philosophical differences, there is some possibility of the breakthrough that most Americans and Cubans want--and which the entire planet has been waiting for. (4) However, it is important to be realistic in our expectations, for as that time-honoured refrain of the “Special Period” in Cuba notes, “no es fácil”… John M. Kirk (1) Office of the Press Secretary, The White House, “Fact Sheet: Charting A New Course on Cuba,” December 17, 2014, p. 3. (2) “Raúl Castro: Compartimos la idea de que puede abrirse una nueva etapa entre EEUU y Cuba,” Cubadebate, December 20, 2014. (3) Office of the Press Secretary, p. 1. (4) In October 2014 the U.N. General Assembly voted—for the 23rd time—to condemn the U.S. embargo of Cuba. Some 188 countries voted in favour of the Cuban position with only 2 (the United States and Israel) opposed, and 3 (Palau, the Marshall Islands and Micronesia, with a combined population of 177,000) abstaining. The Latin American Research Centre University of Calgary Social Sciences 004, 2500 University Dr. NW Calgary, Alberta T2N 1N4 Ph: 403-210-3929 Fax: 403-282-8606 E. [email protected] W. larc.ucalgary.ca If you want to receive our Hot Topics series on a regular basis, please send an email to [email protected] with the subject Hot Topics. Visit our website www.larc.ucalgary.ca to access previous Hot Topics and find information on upcoming events, our newsletter, country profiles, current projects, and research opportunities. A Latin American Research Centre publication

© Copyright 2026