Notes on Castelseprio

ART

THE

292

BULLETIN

It is hoped that some day further researchwill bring ern type of Castelseprioand the Carolingian parallels.

to light facts which will prove conclusivelywhether or I proposed further the view that the frescoes, though

based on Byzantine art, were not of the tenth century,

not this piece was in the Valenti-Gonzaga collection.

as Weitzmann and others maintained, but belonged

rather to the second half of the eighth century at the

UNIONMUSEUM

COOPER

earliestand probablyto the late eighth century, because

of the relations to early Carolingian art and to Italian

works of the end of the eighth and the early ninth

NOTES ON CASTELSEPRIO

century.' This connection with the art of the CaroMEYER SCHAPIRO

lingian period I had already remarked in reviewing

the book of Bognetti and de Capitani d'Arzago in

I. THE THREE-RAYED NIMBUS

1950.4

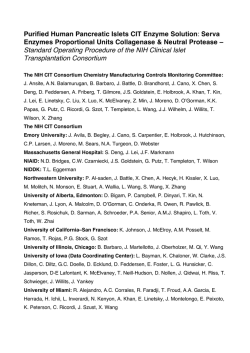

In an article in Cahiers drcheologiques (vII, 1954,

pp. 157-159), Professor Grabar writes that in citing

his observationof the peculiarsymptomaticcross nimbus

in the frescoesof Castelseprio,with the lines of the cross

extending beyond the circle of the nimbus, "M. Schapiro a pens6 pouvoir en r6duire la port&een joignant

aux exemples carolingiens et ottoniens de ce genre de

nimbe crucifere deux exemples byzantins." He goes on

to argue that these two examplesare not at all relevant

to the problem, for in one case-the Cotton Genesis

(Fig. I)'--the arms of the cross are broad bands and

not thin lines as in the frescoes (Fig. 3), and in the

other case-Athens Ms 211, a work of the tenth century-?there is not even a cross nimbus, but rather a

candlestick in the form of a cross, independent of the

nimbus and illustrating a sermon of St. John Chrysostom (Fig. 2). Hence the detail at Castelseprioremains

a Western peculiarityand an evidence of the late date

of the frescoes, since it is found in this form only in

Carolingianand Ottonian works.

I hope this detail will not seem too small and unimportant to warrant further study and the reader's attention; and I hope I shall be forgiven if I take this

opportunity to restate my views on the subject of

Castelseprio.

Although Professor Grabar links my name with

Morey and Bognetti as proposing dates "sensiblement

plus anciennes que l'epoque carolingienne," the conclusion of my article was preciselythat the fresco cycle

could not be of the seventh century, as Morey and

Bognetti believed, since it contains elements which are

first known to us in the art of the Carolingian period.

I regarded the type of cross nimbus as one of these elements, and in citing the two Greek examples I distinguishedtheir form from the more specificallyWest-

In contrasting the form of the cross nimbus in the

Greek and the Western examples, the first with a

"solid, material" cross, the second with "a thin line

[of the cross], an effect more suggestiveof the luminous

and emanatory than of the instrument of the Crucifixion," I wished also to offer an hypothesisto explain

the distinctive features of the cross nimbus in the

frescoes. I supposed that the three ray-like lines, resembling the raysissuingfrom the nimbusof the phoenix

and the personifiedsun in Roman and early Christian

art, symbolizedthe emanatoryaspectof the divinebeing,

the threefold Godhead as a "superessentialray," "an

originating beam," "an overflowing radiance"-metaphors found in the writings of the pseudo-Dionysus.

But such imagery was not peculiarto this Greek writer;

the underlying idea was common enough and had been

expressedearlier and in a manner more pertinentto the

frescoes by a Latin author, Tertullian, in speaking of

the Logos and the Incarnation: "When a ray is projected from the sun it is a portion of the whole sun;

but the sun will be in the ray because it is a ray of the

sun; the substanceof the sun is not separatedbut extended, as light is kindled from light. . . . So from

spirit comes spirit,and God from God .... This ray of

God, as had always been prophesiedbefore, descended

into a Virgin and having been incarnated in her womb

was born a man-God." (Apologeticum xxi. 12-14)

Philo in the first century had already written of the

Logos as "the radiant light of God"' and in the New

Testament the Son is describedas "the brightness of

God's glory" (Hebrews 1:3). In the controversies

during the fourth century over the consubstantialityof

the Father and the Son, the relation of the ray to its

source was the most cogent example of emanation and

of distinct forms with a common substance.6Writing

i. After H. Omont, Miniatures des plus anciens manuscrits

grecs de la Bibliothkque nationale du VIe au XIVe sikcle, Paris,

1929, pl. opp. p. iv.

2. After A. Grabar, Cahiers arch~ologiques, VII, 1954, pl.

G. P. Wetter, PHOS, Uppsala, 1914; Fr. J. D*lger, Antike

379;

und Christentum, I, 1929 ("Sonne und Sonnenstrahle als Gleichnis in der Logostheologie des christlichen Altertums"), pp. 27129o; idem, VI, 194o ("Das Sonnengleichnis in einer Weihnachtspredigt des Bischofs Zeno von Verona. Christus als wahre

und ewige Sonne"), pp. 1-56; R. Bultmann, "Zur Geschichte

der Lichtsymbolik im Altertum," Philologus, xcvII, 1948,

pp. 1-36.

Since the heretical Arians rejected the metaphor of light in

explaining the Trinity (A. Harnack, History of Dogma, London, 1905, Iv, pp.I- , 41), the three-rayed nimbus might be

regarded as more characteristically Western in the fifth and

sixth centuries, for Arianism was more important then in

Italy and Spain than in the East 5 and the frequency of the

three-rayed nimbus in the Carolingian period might be con-

LIV.

3. ART BULLETIN,

XXXIV,

1952,

pp. 156,

I6o,

I62,

163.

4. The Magazine of Art, December, 1950, pp. 3i2f.

5. De Somniis i. 13, 72; cited by Harry A. Wolfson, The

Philosophy of the Church Fathers (I, Faith, Trinity, Incarnation) Cambridge (Mass.), pp. 300, 301.

6. On the analogy of light in early Christian theology and

particularly in the doctrine of the Trinity, see besides Wolfson,

op.cit., pp. 3ooff., 359ff., Cl. Bauemker, Witelo (Beitrige zur

Geschichte der Philosophie und der Theologie des Mittelalters,

III, 2), Miinster, 90o8, pp. 357-433 and especially pp. 371-

NOTES

293

of the Trinityin the symbolicdecorationof the church the light is set abovea cross."The artistof the Athens

of Hagia Sophia,the poet Corippusexclaimed:"Sub- manuscript,or perhapsthe painterof his model, had

sistite,numinafulgent! Natus, non factus,plenumde anothertype of light in mind: one in which a cross

surmountsa lamp." The thoughtunderlyingthisearly

luminelumen."'

In the backgroundof these theologicalmetaphors Christiantype is often expressedin the Greek phrase

was also the conceptionof Christas the true Sun, re- inscribedon the lamp:"The light of Christshinesfor

all."

placingthe pagansolargods.

In the Athensminiaturethe bustof Christas well as

The heavy armsof the crossin the two GreekexamplesI had cited did not seem to me relevantto this the crossissuesfrom the lamp in Adam'shand. The

explanation,although they extend, like the rays at questionis whetherthe crossherealsobelongswith the

Castelseprio,beyond the circle of the nimbus. But nimbusas an attributeof Christor only symbolizesthe

after reading ProfessorGrabar'scommentson my metaphorical

lampstand(or candlestick)of thehomilist.

article,it occurredto me upon furtherstudy that the If the latterwere the case,it would be hardto undermassivecrossesin the Greek examplesalso originated stand why the cross shouldbe set above ratherthan

in a metaphorof God as light and that both typesof below the lamp and why the horizontalarms should

cross nimbus--with broador with thin ray-likearms extend beyond the nimbus; they scarcelylook like

andin any casethe comextendingbeyondthe circle-go backto earlyChristian partsof a standor candlestick,

binationof lampand candlestickseemsstrange.When

models.

Grabarhas observedthat in the Athens National the artistwisheson the samepageto representa candle

LibraryMS211 the miniatureshowinga bustof Christ in the handsof the angels,he drawsit clearlyenough,

with threearmsof a crossreachingbeyondthe nimbus and wherehe wishesto depicta crossdistinctfromthe

(Fig. 2) rendersvery preciselythe wordsof a sermon nimbus,as in his drawingof the Holy Spiriton another

by St. John Chrysostomon the parableof the ten leaf, the cross is set behind rather than within the

drachmas(Luke I5:8-Io). Christ,accordingto Gra- nimbus,in passingbeyondit."2Grabarinterpretsthis

bar, is the tenth drachmaand is held by Adam in a crossas an actualmetalobjectplacedon an altar; but

lamp; the other nine are the accompanyingangels. he ignoresthe materialprototypesof the lamp in the

The bust of Christwith the doubletraversecrossbe- miniatureof the tenth drachma.

hindhim illustratesthe wordsof the homilistfor whom

Is it not moreplausibleto supposethat the artist,in

Christis the Divine Wisdom "whichlights the lamp order to symbolizethe illuminationby Christ, "the

and placingit in the lampstandof the Cross,bearsthe light of the world," the "lucernaardenset lucens"

light and leads the whole world to piety." Christ (Augustine),and to renderthe homilist'simageof the

"comesfrom heaven,takesthe clay lampwhich is the crossas the lampstandor candlestick,

hascondensedthe

body,lightsit with the light of divinity,and sets up the chain of metaphorsin a cross nimbus of decidedly

candlestickof the cross."What I had taken to be a radiantaspect?The color re-enforcesthis effect: the

cross nimbusis therefore,in Grabar'sopinion,quite nimbus,the cross,and Christ'sapparelare all painted

anotherthing; the cross, symbolizingthe candlestick yellow.

and renderingliterallythe text of the accompanying That light could be representedin this more solid

sermon, "has nothingto do with the crossnimbus."8 form and even with a thickeningof the raysor bands

I am not convincedby ProfessorGrabar'sinterpre- at the outerend is confirmedby the imageof Heliosin

tation.Is not the tenth drachmaAdam who holdsthe the recentlydiscoveredceilingmosaicin the pre-Conlamp?9and is not Christthe light by whichAdam,the stantinianmausoleumunderneathSt. Peter'sin Rome

lost drachma,is found? In identifyingthe cross of (Fig. 4)." The purplishrays,formingmassivebundles,

Christ with the lampstand(lychnia) that bears the extend beyondthe halo as in the Cotton Genesisand

light, the author of the sermon describesa familiar the Athensmanuscript.

But even withoutthe testimonyof this mosaic,one

object of his time: a candelabrumor stand of which

nectedwith the controversiesover Adoptianismand the Filioque chritienneet de liturgie,s.v. "Lampe,"cols. Iio6ff., I202,

formula at that time, although these two questionswere in- x209, I2xo; Fr. J. D6ager, Antike und Christentum, v, 1936,

dependentof the old Arian issue.

pls. I, II.

12. On fol. 56, cf. Grabar, loc.cit., 1932, pl. xviii, 2 and

7. For the whole text, see A. Heisenberg'sarticle in Xenia,

Hommage international ai l'Universite nationale de Grice,

pp. 263, 278. Cf. for a similar effect the cross with a medallion

Athens, 1912, p. 152.

8. Op.cit., p. 158.

9. As the sermon clearly states (Migne, Pat. gr., LXI, col.

781) and as Grabar recognized in his publication of the miniature in 1932: "Un manuscrit des homilies de Saint Jean

Chrysostome a la Bibliotheque nationale d'Athenes (Athenensis

211 ) ," Seminarium Kondakovianum, Recueil d'ktudes, Prague,

v, I932, pp. 259-297, especially p. 272. Although attributed

to St. John Chrysostom in the manuscript, this sermon is published in Migne among the spuria.

0o. For an example see H. Leclercq, Manuel d'archdologie

chritienne,

Paris,

1907,

II, p. 570, fig. 379 (Cairo

ix. For examples see Cabrol, Dictionnaire

Museum).

d'archiologie

bust of Christ in front of the cross in Paris, Bibl. nat., Ms gr.

20, fol. 7.

13. See Esplorazioni sotto la confessione di San Pietro in

Vaticano, ed. by B. M. A. Ghetti et al., Vatican City, 195p,

I, p. 41, pls. B, C (in color, ii, pl. xI from which our Fig. 4

is reproduced) 5 Jocelyn Toynbee and J. Ward Perkins, The

Shrine of St. Peter and the Vatican Excavations, London, 2956,

pp. 42, x 7, pl. 32. Toynbee and Perkins date the mosaic in

the mid-third century and call the figure Christus-Helios: "It

may be no accident that the rays to right and left of his nimbus

trace strongly accented horizontal lines, forcibly suggesting

the transverse bars of a cross."

THE

294

ART

BULLETIN

could have surmised the possibilityfrom other works."'

There is one especiallyin which the connection of the

cross with solid bands of emanating light is perfectly

clear; the mosaic of the bema of the church of the

Dormition at Nicaea.15Here eight broad bands of light

issue from a cross set on the throne of the Hetoimasia;

four of these prolong the arms and vertical parts of the

cross, the other four issue from the angles. They all

traverse three great concentric circles which probably

symbolize the Trinity. In the same church the mosaic

of the apse repeatsthe theme of light in a more explicit

Trinitarian sense: three rays in the form of bands issue

from the hand of God, passing through two concentric

circular segments into the semicircular golden space

below."1

Let us note too that these unquestionablerays of

light are of changing color: white, grey-blue, and greenblue in the first mosaic; rose, grey, and green in the

second. Professor Bognetti has objected to the interpretation of the three lines of the cross nimbus in Castelseprio as rays or symbols of light that they are painted

in a darkcolor." This is due, I believe,to the fact that

they are set on the light groundof the nimbus.In the

mosaicbelow St. Peter's, as in the later mosaicsin

Nicaea and in many other works, rays of light are

representedin dark tones (grey, blue, green, and

purple)."sBlackraysare not uncommonin mediaeval

sun."9The colorof raysvaries

imagesof the personified

in mediaevalart just like the colorof the nimbus,anothersymbolof light.

I maypointoutfinallythatin Carolingian

artthesolid

crosswith armsprojectingbeyondthe nimbusis sometimes formedof parallellinear rays closelyaligned.20

Hence from the pointof view of theologicalmeaning and origin-though not of style-the Carolingian

examplesof the nimbuswith the linearray crossneed

not be separated,as I oncesupposed,

fromthe solidtype.

Both dependprobablyon modelsof the fourthor fifth

century--the periodduring which the solar analogy

was common and Helios was representedwith rays

issuingfrom the nimbusin the two formsthat I have

The theologicallysignificantchoiceof the

described.2'

14. For the same type of rayed nimbus as in the mosaic

under St. Peter's, cf. the painting of Helios in the Vatican

Virgil (lat. MS 3225), (Fragmenta et picturae Vergiliana,

Rome, 1930, pl. 6) the pavement mosaic of the phoenix in

Antioch (Doro Levi, Antioch Mosaic Pavements, Princeton,

1947, II, pl. LXXXIII); the mosaic of Christ on the arch of

triumph of S. Paolo f.l.m. in Rome, which may be of the late

eighth century (M. van Berchem and E. Clouzot, Les mosaiques

de l'Institut de philologie et d'histoire orientales et slaves

(Universit6 Libre de Bruxelles) Ix, 1949, pp. 593ff. Visions

of the luminous cross are also mentioned in Gnostic-Christian

writings (Acts of John and Philip) (R. A. Lipsius, Die

apokryphen Apostelgeschichten und Apostellegenden, 1883900oo,I, pp. 452, 5235 III, pp. 9, 16, 37). In the Acts of

John, which were read at the Council of Nicaea, Christ shows

John a luminous cross which he calls Logos, Nous, Spirit and

Life, as well as Christ.

I6. Schmit, op.cit., pl. xx, pp. 29, 30.

17. See Cahiers arch~ologiques, viI, i954, p. 143 n. 2.

18. Cf. also the sun in the scene of Joshua's miracle in the

mosaics of S. Maria Maggiore in Rome; the miniature of

Joseph's Dream in the Vienna Genesis (Fr. Wickhoff, Die

Wiener Genesis, Vienna 1895, pl. 29); the painting of Apollo

in Pompeii cited in note 14 above; the bust of the sun in

British Museum, Harley Ms 647, fol. 13v (Catalogue of

Astrological and Mythological Manuscripts of the Latin Middle Ages, III, Manuscripts in English Libraries, by Fr. Saxl

and Hans Meier, edited by Harry Bober, London, 1953, II,

pl. LVII, fig. 148); the sun in Madrid, Bibl. Nac. Ms 19

(A. 16) (ibid., I, fig. 9).

19. Cf. the Leyden Aratus (Voss. 69) (Thiele, op.cit., p.

121,

fig. 46 [three black and three gold rays])5 British

Museum, Cotton Tiberius C. I (Saxl, Meier, and Bober, op.cit.,

chritiennes,

Geneva,

1924, figs. 100,

101, p. 89);

the Romano-

British relief of Sol Invictus in Corbridge (T. D. Kendrick,

Anglo-Saxon Art to A.D. 900, London, 1938, pl. XIII, I:

here the slender rays crossing the nimbus may be regarded as

lines rather than as solid bands). More common are the solid

pointed, i.e. peaked or convergent, rays passing across the

nimbus: the figure of Apollo in a Pompeian fresco (0. Brendel,

R'mische Mittgeilungen, LI, 1936, p. 57, fig. 8); the relief

of Mithras in Nimrud Dagh (Fr. Sarre, Die Kunst des alten

Persiens, Berlin, 1923, pl. 56); the solar personifications in

Mithraic art (Fr. Cumont, Textes et monuments relatifs aux

mystires de Mithra, Brussels, I894-1900, II, fig. 29, p. 202

[no. 18] and passim); coins of Antoninus Pius (Daremberg

et Saglio, Dictionnaire des antiquitis grecques et romaines, s.v.

"Nimbe," fig. 5321); for mediaeval examples, cf. the sun in

Joshua's miracle of the sun in the Vatican Joshua Roll, the

bust of the Sun in Phillips Ms 1830 (Thiele, Antike Himmelsbilder, Berlin, 1898, fig. 72).

Theodor Schmit, Die Koimesis-Kirche von Nikaia,

i5.

Berlin and Leipzig, 1927, pl. XII, p. 21; O. Wulff, Die

Koimesis Kirche in Niciia und i/re Mosaiken, Strasbourg,

1903, pl. I. For other examples of bands of light extending

from the cross beyond the enclosing circle, cf. the fresco of

the sixth century in the apse of the annex to the cathedral of

Rusafa-Sergiopolis (J. Lassus, Sanctuaires chretiens de Syrie,

Paris, 1947, fig. Io9) ; fresco in tomb chamber in Sofia, sixth

century (E. K. Riedin, The Christian Topography of Cosmas

Indicopleustes [in Russian], Moscow, 1916, fig. 2, p. 6) ;

mosaic of Hagia Sophia in Salonica (van Berchem and Clouzot,

op.cit., p. 182); a newly uncovered mosaic in Hagia Sophia

in Istanbul (Dumbarton Oaks Papers, Ix and x, I956, fig. iio,

after p. 300). For the possible connection of the luminous cross

in painting and mosaic with early Christian legends about the

luminosity of the true cross and the miraculous appearance of

a radiant cross in the sky over Jerusalem in 351 (or 353), see

O. Wulff, op.cit., pp. 241, 243 and A. Grabar, Martyrium,

Paris, 1946, II, p. 276; for the occasion and date of Cyril's

vision of the celestial cross, see J. Vogt, "Berichte iiber

Kreuzerscheinungen aus dem 4. Jahrhundert n.Chr.," Annuaire

I, fig. 147).

20. Cf. the Egino codex, Berlin Phillips Ms

1676, fol. 24

(E. Arslan, "La pittura e la scultura veronese dal secolo VIII

al secolo XIII," Milan, 1943, pl. 42)5 the Lorsch Gospels

(Boinet, La miniature carolingienne, Paris, 1913, pl. xvI, A) ;

the Gospels of Soissons (Bibl. nat. MS lat. 8850) (in ibid., pl.

xx); the Smyrna Physiologus, bands of triple rays from the

bust of the Sun (J. Strzygowski, Der Bilderkreis des griechischen Physiologus, Leipzig, 1899, pl. Iv). Such bands are common in images of the Anastasis, issuing from Christ's body. Cf.

the mosaic in the chapel of S. Zeno in Sta. Prassede, Rome

(J. Wilpert, Die r6mischen Mosaiken und Malereien, Freiburg

im Br., 1917, pl. 114, 4).

21. For the Sun or Helios with single linear rays, cf. the

Joshua scene in the Rabula Gospels, and the relief of the Sun

in Corbridge cited in note 14 above. Both types of rays, the

solid band and the linear, occur also in images of the phoenix:

for the first, see the mosaic in Antioch cited in note I4; for

the linear type, see examples I have cited in ART BULLETIN,

1952, p. 156 n. 56; for a list of examples on Roman coins, see

L. Stephani, "Nimbus und Strahlenkranz," Mimoires de

l'Acadimie Impiriale des Sciences de St. Pitersbourg, 6e sBrie

na t-?

•s

!

?w~~i

00 Cta.40,

o~C"

h~o•••.•

::':•:i:::

•i

uaoEr0

•.IU,

d.•!

•'

.'.,/K

i,)..

'4

. ...

'

.,/

41b

.•.•.•; ..,

IT01 - I

,

' "

.

-," -

4

"t....,,II

(A..

i. Creation, The Third Day

(detail)

Cotton Genesis (Drawing after L::

destroyed1kminiature)

2.

!a

%4

X,,'.

The Tenth Drachma, Homilies of St. John Chrysostom

Athens, National Library, ms z i i, fol. 34.V

1~1*

~~!

.. .

A7

0

'.'.•

I.

-

~,"r~rj

3. Adoration of the MagiCatlero

Sta. Maria (Drawingafefrso

i-t...

.:: r,.

I

,k

a~

~

ebN

t: tA

-rc

miniature)'

destoye

?/

,F

t

..

5.

.1exnde

/

•

;,•

edalio

Gratbroze

th

Rom,

Vticn

Mseu

5. Alexander the Great, bronze medallion

Rome, Vatican Museum

4. Helios, ceiling mosaic of underground mausoleum

Rome, St. Peter's

6. Dusseldorf, Landesbibliothek, Ms

3

N

-

•i~i!

ir_

al

i

j\"i.•

%LL

8. Crucifixion. Engraved Gem. London, British Museum

7. Christ Enthroned. Vercelli, Biblioteca Capitolare,

MS CLXV

YE)

9. Annunciation to Joseph. Castelseprio, Sta. Maria (Courtesy Frick Art Reference Library)

iIi

fA

A

o. Mounted Amazons Silk

Lyons Collection C. Cote

Tapestry.

Giraudon)

(photo"

iA

s s. The EmGperor Theodosius II. Vercelli,

Biblioteca Capitolare, MS CLXv

NOTES

three rays of Christ's halo may be likened to the seven

rays of the sun in Mithraic art, also a theological attribute.22

The recurrence of the solid emanatory cross in the

Creation scenes of the Cotton Genesis agrees with the

theology that speaks of the divine light especially in

connection with the Creation. In the same miniature

(Fig. i) the nimbus is marked with many small rays, a

device that reappearsin Carolingianart.

(I have assumed until now that the three rays are

parts of the cross and merely a variant of the "cross

nimbus." But the facts presented here suggest another

interpretation:that besides the true cross nimbus and

monogram nimbus in which all four bars were more

or less clearly drawn-as in the mosaics of Sta. Maria

Maggiore and the door of Sta. Sabina23-there existed

very early a three-rayednimbus of which the rays were

at first conceivedless as partsof a cross than as a symbol

of the Trinity. In time this emblem was conflated with

the cross in the familiar form in which the fourth part

is covered by Christ's head. It is a remarkablefact that

although Christian art develops from naturalistic to

increasinglysymbolicmodes of representationand tends

to present its symbols as distinct surface forms, the

cross in the nimbus remains a symbolic object in real

space overlappedand obscuredby the head of Christ.)

The tiny stroke at the end of the rays in Castelseprio

(and in several other Western works) seems to Bognetti incompatible with the interpretation of the lines

295

as rays.2"This is hardly a decisive objection since the

rays in the image of Helios beneath St. Peter's in Rome

(Fig. 4) are thickened at the end. In early Christian

mosaics stars are often, if not usually, represented by

radiating lines with knobbed ends;25 this, in fact, is

how the painter of Castelsepriohas drawn the great

star of Bethlehem in the scene of the Nativity. In pagan

and Christian works the rays of the sun and of solar

divinities end in dots or knobs that might symbolize

the stars or planets,26 a device which survives into the

Middle Ages, especiallyin pictures of the Apocalyptic

Woman "clothed with the sun" (Revelations 12).27

On a medallionof the late fourth century in the Vatican

Museum, the emblem of the sun accompanyinga head

of Alexander the Great is a circle from which radiate

wheel-like spokes with short transverse lines at the

ends (Fig. 5).28 This schema for rays of light is not

uncommon in Christian art. Similar nail-headed rays

appear on the stars in the mosaic of Sta. Agnese in

Rome29 and in the frescoes of Civate and SaintSavin;so they may be seen too in the personificationof

Day in the Gumpert Bible in Erlangen."s The nailheaded form in Castelsepriomay therefore be regarded

as a variant of an older convention for the luminous

cross. Even if the end strokes are derived from a type

of cross, the arms extended beyond the nimbusmay still

be interpreted as ray-like elements which owe their

characterto the theological metaphorof Christ as light.

I am not at all sure that the cross with projecting

(Sciencespolitiques,histoire et philologie), Ix, 1859, pp. 444- pp. 84ff.); the nimbedbust of the Sun in VaticanMs gr. 699;

446. For the nimbus with linear rays on solar figures carved Cosmas Indicopleustes (C. Stornaiolo, Le miniature della

on amulets, see Campbell Bonner, Studies in Magical Amulets,

Ann Arbor, 195o, pl. xi, no. 236, pl. Iv, nos. 83 and 86; and

the same writer's article "Amuletschiefly in the British Museum," Hesperia, xx, 1951, pl. 97, no. 32.

topografia cristiana di Cosma Indicopleuste, Milan, g908, pl.

52) ; Sacramentaryof Henry II, Bamberg (A. Goldschmidt,

German Illumination, II, pl. 75); solar emblems on Gaulish

coins (A. Blanchet, Manuel du numismatique franpaise, I, 1912,

fig. 107). F. D5lger, Antike und Christentum, vi, i, 1940,

22. An interestingparallel to the three rays of Christ is the

description by the Carolingian poet, Sedulius Scottus (carm. p. 31, interpretsthe end-pointsor knobs of the rayed nimbus

3'), of an image of the personifiedMedicina painted in a or solar wheel as points of light (apices) rather than as stars.

27. Cf. the Bamberg Apocalypse (H. Walfflin, Die Bamhospital-she is representedwith three rays issuing from her

brow: "Haec regina potens rutilo descendit Olimpo. . . berger Apokalypse, Munich, 192i, pls. 29, 31); Valenciennes,

Fronteque florigera cui lumina terna coruscant." (J. von Bibl. mun. Ms 99, fol. 23 (Bulletin de' la Sociite Franpaise

Schlosser, Schriftquellen zur Geschichte der karolingischen

Kunst, Vienna, 1896, p. 381, no. 1027.) The analogy with

Peintures, 6e annie,

pour la Riproduction des Manuscrits

1922, pl. xxIII); Paris, Bibl. Nat., Nouv. Acq. lat. Ms 1132,

schrift, xxx, 1929-1930,

pp. 587-595, and especially p. 593.

24. See Cahiers archiologiques, viI, pp. 143, 144.

25. Cf. the mosaicsof Sta. Maria Maggiore, Rome, Adoration of the Magi (van Berchem and Clouzot, op.cit., fig. 51);

Naples, Baptisterydome (ibid., fig. i i9); Albenga, Baptistery

(ibid., fig. 128); Ravenna, S. Apollinare in Classe (ibid., fig.

the Cambrai Apocalypse (Boinet, op.cit., pl. io6 B);

202);

28. See Andreas Alfoildi, Die Kontorniaten, Ein verkanntes

Propagandamittel der stadtr6mischen Aristokratie in ihrem

Kampfe gegen das christliche Kaisertum, Budapest, 1943, I,

p. 133, no. 34, 11, pl. xLIII, 7; Jocelyn M. C. Toynbee, Roman

Medallions (Numismatic Studies, No. 5, The American Numismatic Society), New York, 1944, p. 236, n. 34, and pl.

Christ dependedperhapson the metaphorof Christ as medicus fol. 17. Cf. also angels with rayed nimbus and dots or little

or archiater common since Origen. See R. Arbesmann,"The circles at the ends of the rays, in Trier MS 31 (Apocalypse),

Concept of 'ChristusMedicus' in St. Augustine," Traditio, x, fol. 22; Cambrai Ms 386 (Apocalypse), fol. 13; Madrid,

Bibl. Nac. HH58 (Beatus), fol. 96v, 97; Annunciationby

1954, pp. Iff.

23. On the early types, see E. Weigand, "Der Monogramm- Filippo Lippi, National Gallery, Washington, D.C. (rays

nimbusauf der Tiir von S. Sabinain Rom," ByzantinischeZeit- with knobbedends).

the Milan gold altar of Vuolvinus, Nativity and Christ in

Glory; Codex Egberti,

lumination, II, pl. 6).

Magi,

(Goldschmidt,

German Il-

xxxxx, 5 (photograph). The same nail-headedrays appear on

amuletsof Chnoubis,a lion-headedsnakewith solar affinities-see Bonner, in Hesperia, XX, I951, pp. 339, 340, no. 65, and

pl. 99, and copies in nos. 66, 67. Bonner regards all three as

26. Cf. a Chnubisamulet reproducedby E. R. Goodenough, modern works based possibly on old models (see pp. 3o8f.).

29. Van Berchem and Clouzot, op.cit., fig. 247.

Jewish Symbols in the Graeco-Roman Period, New York, 1953,

30. In Civate, in the Apocalyptic Vision of the Dragon; in

III, fig. Io96; a statue of Attis from Ostia in the Lateran

Museum (F. Cumont, Les religions orientales dans le paganSaint-Savin, in the Creation of the Sun and Moon.

isme romain, 4th ed., Paris, I929, pl. IV, opp. p. 66); a

31. Georg Swarzenski, Die salzburger Malerei, Leipzig,

Gallo-Roman bronze figure of Dispater in the Walters Art 1914, 11, pl. xxxiv, fig. I 4.

Gallery (The Journal of the Walters Art Gallery, x, 1947,

296

THE

ART

BULLETIN

arms, whether solid or ray-like, was in every case designed to expressthe metaphoricalluminosityof Christ.

In some examples it might have been repeated as a

fossilized type without thought of its figurative meaning, much like words of which the original sense has

been lost. That the old meaning was still alive in the

region of Castelseprioat the end of the eighth century

seems evident, however, from the radiant aspect of the

cross on the medallion bust of Christ in the Egino

codex, a manuscript of homilies of the Latin church

fathers, which was written in Verona between 790 and

The three arms of the cross passing beyond the

799•82

circular frame are formed by bundles of rays. In another Lombard manuscript of the ninth century, the

Homilies of Gregory in the Chapter library of Vercelli

(MS CXLVIII),an ordinary closed cross nimbus is inscribed LUX, with one letter on each of the three solid

members of the cross.33

For the problem of the frescoes of Castelseprio-their date, their place in mediaeval art-it does not

matter perhapswhether the ray-like form of the cross

was conceived explicitly as a symbol of the divine light

or was only an inherited convention adopted because

of its congenial form. The rendering of the arms of the

cross by a rapid stroke reaching beyond the nimbus

seems to accord better with the impulsive sketchy style

of the artist than would a massive form. In the medallion bust of Christ in the same series, the cross is of the

more common type and is confined by the nimbus; but

this painting of Christ already suggests another attitude

of the artist-he is reproducingan iconic image, frontal

and severe, and acceptsthe conventionsof the canonical

model which are in principle opposed to the forms of

his own art.

Grabar believes, however, that the varieties of the

rayed cross nimbus have some historical significance

and provide a means of dating the frescoes. In another

article in which he deals more specificallywith the different types of cross that project beyond the nimbus,

Grabar distinguishesnot only between the thin and the

solid form but also between the thin cross with the

terminal stroke, like a nail head, as in Castelseprio,and

the thin cross without this element."4Carolingianartists

knew the latter, but Grabar has found examples of the

Castelsepriotype only in Ottonian works. He asserts

that while Carolingian artists invented the projecting

linear type, it was in the Ottonian period that the thin

cross first acquired the terminal strokes. From this he

concludes that although the painter of Castelsepriowas

strongly influenced by the art of Constantinople,these

frescoes are related to the Ottonian Renaissance and

must be more or less contemporarywith the Ottonian

miniatures in which the same type of cross appears."5

This is a surprisinginference, since it would bring

the date of the frescoesinto the second half of the tenth

century or even into the eleventh--the Salzburg manuscript which he has cited as the Ottonian parallel

(Morgan MS 780) was made about 1070. Elsewhere

he has spokenof the frescoes as works of the ninth century, and has admitted the possibilityof a still earlier

date in the Carolingian period."6

But it is unnecessary to go beyond his article in

order to criticize his reasoning or the fluctuationin his

dating of Castelseprio. For precisely this form of the

nimbed cross with the nail-head ending of the rays

occurs in Carolingian manuscripts:the Stuttgart and

Utrecht Psalters, a fragment now in Diisseldorf which

comes from the same center or school as the Utrecht

Psalter (Fig. 6),8 and, in the region of Castelseprio,

the Canons of Councils in the Chapter Library of

Vercelli (Fig. 7)o." All these, except the latter, are

listed by Grabar in his article, but he has overlooked

the terminal strokes of the cross and classifiedthe examples in these manuscriptswith the plain Carolingian

types.

The criterion on which Grabar built his conclusion

should requirehim then to date the frescoesearly in the

Carolingian period. But it would be imprudentto base

the dating on a single detail of which the history is still

so little known. If the frescoes are to be placed in the

later eighth century, as I have supposed,it is for a number of reasons beside the evidence of the rayed cross.

The latter has some value, however, since of the many

surviving works with the cross nimbus, none before the

Carolingian period shows the peculiar form that occurs

in Castelseprio,and the Carolingian works that present

this form share other traits with the frescoes.

Future discoveriesmay discloseexamplesof this cross

older than the Carolingian works. To Grabar's belief

that the simple linear cross extending beyond the

nimbus, but without the terminal strokes, was a

Carolingian invention one can oppose an engraved

gem in the British Museum attributed to the early

Christian period (Fig. 8).89 It is a red jasper found

32. Berlin, Staatsbibliothek, Phillips MS 1676 (E. Arslan,

op.cit., pp. 42, 43)33. See Noemi Gabrielli, "Le miniature delle omelie di San

Gregorio," Arte del primo millennio (Atti del IIO Convegno

per lo studio dell'Arte dell'alto medioevo, Pavia, i950) Turin,

n.d., pl. 149, pp. 3oIff. The same inscription LUX appears

also in Vercelli, Bibl. capitolare MS LXII, fol. zzv, Io3r.

34. "Les fresques de Castelseprio et l'occident," Friihmittelalterliche Kunst in den Alpenlandern (Akten zum III. internationalen Kongress fuir Friihmittelalterforschung, September

9-14, 1951), Olten and Lausanne, 1954, pp. 85-93.

35. Ibid., p. 89.

36. "Les fresques de Castelseprio," Gazette des Beaux-Arts,

July 1950 (published in 195x), pp. o17-xx4, and especially

pp. x 13, 14. See also Grabar's book, Byzantine Painting, New

York, 1953, p. 86.

37. Landesbibliothek, Ms 113, a fragment of Rabanus Maurus, De institutione clericorum; another example in a missal

of the tenth century in the same library (Ms D 3), in a drawing of the Crucifixion. Cf. also Carolingian examples in the

Marmoutiers sacramentary, Autun, Bibl. mun. Ms I9 bis

(Boinet, op.cit., pl. XLI), and Nancy evangiles (ibid., pl.

xxvii). For a clear example of the nimbus with nail-head rays

in the Utrecht psalter, see E. T. DeWald, The illustrations of

the Utrecht Psalter, Princeton, 1932, pl. xcI (fol. 57r).

38. MS CLXV.Cf. N. Gabrielli, op.cit., (note 33 above),

pp. 303ff. from which our Figs. 7 and I I are reproduced.

39. See A. de Longpirier and E. Le Blant in Mimoires de

la SocietWdes Antiquaires de France, xxx, 1866, p. III. The

gem is now in the British Museum (no. 5623x) and has been

NOTES

297

silkswith the same motif of the Amazons."'I cannot

regardas relevantMorey'sobservationthat the davus

"is of the samecharacacrossthe thighin Castelseprio

ter as the waistbandworn by David in the miniature

of the Penitencein the ParisPsalter."

One can hardlybe sure that thispeculiarbandwas

first usedin the eighthcentury;but until now I have

foundit in no worksthat can be securelydatedbefore

thistime.It couldhavebeena fashionin Constantinople

(or some other center) for a shorttime in the eighth

century,from which little of the art producedin the

capitalhas come down; such a form might have per2. THE CLAVUSON THE THIGH

sistedlonger in the art of provincialregions,like Italy

I passto another detail of the frescoeswhich has been and France,where it had been acceptedas a pictorial

a matter of dispute.In my articleon CastelseprioI elementratherthan as part of real costume.The fact

called attention to a peculiarityof costume that might thatamongsurvivingworksthe transverseclavusspanserve as an indicationof the date and perhapsthrow ning the thighfirstappearsin the West after the comlight on the origin of the work. It is the transverse mon use therein the seventhand eighthcenturiesof an

ornamentalbandsewn acrossthe middleof the thigh older Easterntypeof appliqu6on the thigh," seemsto

on the long tunic or the mantle (Fig. 9), an element confirmits laterorigin.

that is frequentin Carolingianand Italianart of the

For the possibility

that the Carolingianartistscopied

late eighth and ninth centuries."It was precededin this detail from a much earliermodel there is some

the seventhand eighthcenturiesby a relatedform-the indicationin a manuscriptthat I have cited:the illusshorterparagaudae-thatsurvivedinto the ninth cen- tratedSeduliusin the Mus6ePlantinin Antwerp (Ms

too from anotherorna- 126). The modelsof the miniaturesin this book,actury; it must be distinguished

the

on

horizontal

hose." Morey objected cordingto ProfessorWilhelm Koehler,our bestjudge

bands

ment,

to usingthisbit of costumeas an evidenceof a date in in thesematters,were Italianpaintingsof about

500.'8

the eighthcenturysincehe believedthat it had already But betweenthe Italianprototypes

and the Carolingian

occurredin a work of the sixth."5But in the figuresof copy there were undoubtedlymediatingversionsof

mountedAmazonson the silk fabricin the Cote Col- which one was preservedin England; an inscription

lectionin Lyons whichhe has cited,I find no traceof in the Antwerpcodexreproducedfroman earliercopy

such a transverseclavus acrossthe thigh (Fig. io). namesan owner Cuduuinus,whom Traube identified

Morey has mistakenfor the element I had described as the Bishopof Dunwichbetween716 and 731 ." The

a simplehem at the lower edge of a shorttunic that transverseclavusin theseminiaturesmay belongto the

reachesto the thigh.The sameformreappears

in other model of 5oo00

or to an Italianor insularcopy--whatin Gaza, with a scene of the Crucifixionand an undecipheredinscriptionthat Le Blant believedwas of

gnosticorigin." I cannotsay more aboutthis object;

its dateis uncertainand nothingdecisiveseemsto have

beenaddedto the commentsof de Longperierand Le

Blant publishedin 1867." On the other hand, the

broad-armedcrossextendingbeyondthe nimbus,as it

appearsin the Cotton Genesis,is less rarein the early

Christianperiodthan I had supposed.It is foundalso

on two engravedgemsin CambridgeandThe Hague.'2

the late eighth century.

44. As on the hose of a Persian Magus in the Adoration

scene in the Menologion of Basil II in Vatican

MS gr. 1613

(Weitzmann, The Fresco Cycle of S. Maria di Castelseprio,

40. A. de Longpirier and E. Le Blant, loc.cit.

Princeton, 1951, fig. 66), and as on the costumeof lay figures

41. For later commentsee, besidesBonner, loc.cit., L. Br&- in the tenth centuryAthens MS2 x (reproducedby Grabarin

hier, L'art chritien, 2nd ed., Paris, 2928, p. 8 i; R. Zahn and Recueil d'itudes, Seminarium Kondakovianum, Prague, v,

J. Reil, "OrpheosBakkikos," Angelos II, 1926, pp. 63, 64; 1932, pl. xvIII, 2).

J. Reil, Christusam Kreuz in der Bildkunstder Karolingerzeit,

45. "Castelseprio and the Byzantine Renaissance," ARTBULLeipzig, 1930, p. 3.

LETIN, XXXIV, 1952, p. 199 n. 7o.

42. See Cabrol, Dictionnaire, s.v. "Gemmes,"col. 846, fig.

46. Cf. the piece in Cologne--Peirce and Tyler, L'Art

reproduced by Bonner, op.cit., Hesperia, xx, 1951, pp. 336,

337, no. 54, pl. 98. For this informationI am grateful to Mr.

John Beckwith and Dr. A. A. Barb. Our Fig. 8 is from the

engraving in Cabrol, Dictionnaire, s. "Gemmes,"fig. 4945.

5088 (The Hague, Museum, Entry into Jerusalem), fig. 5090

Byzantin, nI, pl. I85, and also Ars Orientalis, I, 1954, opp.

(Lewis Collection, CorpusChristi College, Cambridge,Cruci- p. 192 for an example in DumbartonOaks and one formerly

in the Sangiorgi Collection. Dr. Florence Day (ibid., p. 240)

fixion). On the latter see also E. Babelon, Bulletin de la Sociite

des Antiquaires de France, LVII,

pp. 194, 195-he at- cites the shroud of St. Fridolin as the earliest example of the

tributes the gem to Syria in thex896,

seventh or eighth century. Amazon motif in silk, dating it in the sixth century,but notes

Note also a trace of the same type of rayed cross nimbus in that the type continuesinto the eighth centuryand into Islamic

the encolpium of a gold cross in the Dzyalinska collection at art.

Goluchow, an Italian work attributedvariously to the sixth,

47. See ART BULLETIN, XXXIV, 1952, p. i6o, for a brief

seventh and eighth centuries (Cabrol, Dictionnaire, s.v. "As- account of its history.

somption," col. 2993, fig. 1027).

48. "Die Denkmailerder karolingischenKunst in Belgien"

43. See ART BULLETIN,XXXIV,1952, p. I6o. To the exam-

in Belgische

Kunstdenkmdiler, Munich, 1923, pp. 9,

figs.

x9,

ples listed there should be added the ValenciennesApocalypse 8, 9.

(Ms 99, fol. 3) and the recently discovered frescoes of the

49. In the Neues Archiv der Gesellschaftfifr altere deutsche

ninth centuryin St. John at Miistair (Switzerland) (L. Birch- Geschichtskunde,

9xxviI, 09o, pp. 267ff. A. S. Cook has identiler, "Zur karolingischenArchitekturund Malerei in Miinster- fied the name with another person ("Bishop Cuthwini of

Miistair," Frilhmittelalterliche

Kunst in den Alpenliindern,

Leicester [68o-691],"

Speculum, II, 1927, pp. 253-257);

but

Olten and Lausanne,1954, pp. 167-252, fig. 96). An example W. Levison, England and the Continent, 1946, pp. 133, 134,

in the Morgan Library Beatus, Ms 644, fol. 9v (also fol. has rejectedCook's opinion and supportedTraube.

I8Iv), early tenth century, may go back to the model of

298

THE

ART

BULLETIN

ever its date-or it may have been introduced for the

first time in the Carolingian version." The initial P

on folio 8 is clearly of the later eighth or ninth century

and the furniture, too, points to this period. If the

miniaturesdepend ultimately on prototypesof the early

sixth century, this fact does not entail the same date for

the ornament of the costume.

The same questionarisesfor the Trier Apocalypse,a

work attributedby Goldschmidtto the end of the eighth

century."5The transversethigh band occurs here often

in the form which we observe at Castelseprio; and

since the illustrations in this manuscript were copied

from older models, perhaps of the sixth century, one

must consider the possibilitythat this detail was part of

the original work. There are two reasons, however,

for doubting this. First, the thigh band, so frequent in

the Trier Apocalypse, does not appear in the Carolingian sister manuscriptin Cambrai (386) which surely

descended from the same prototype." In the second

place, the thigh band does occur on a flyleaf of the

Trier manuscript in an early Carolingian drawing of

Christ Treading on the Beasts, which is independent

of the illustrations of the Apocalypse and by another

hand.5"It is close in style to the Genoels-Elderen ivory

plaques in Brussels, where the same thigh band is

" these

rendered;

ivory carvings are of the late eighth

century and combine insular and Italian features-they have been commonly placed in or near the region

of the Ada School."5I had noted before their relation

in iconography to the frescoes of Castelseprio (Annunciation, Visitation);" to which may be added-as

of some interest for the North Italian, as distinguished

from the Roman, connections of Carolingian art-the

resemblanceof the draperyforms in these ivory panels,

and particularlyof ChristTreading on the Beasts,to the

stucco figures of the eighth century in Cividale."7

There is a North Italian work which supports the

possibilitythat the motif of the thigh band, as it appears

in the Antwerp manuscriptof Sedulius and the Trier

Apocalypse,alreadyexistedin the first half of the eighth

century. In the sculpturedpanels of the altar in Cividale, dedicated around 737 to the memory of Duke

Pemmo (d. 734) by his son Ratchis, the transverse

stripes on the robes of the angels"5seem to represent

triplebandsof clavilike thoseon severalfiguresin the

Sedulius manuscriptand particularlyon the flying

angel in the sceneof Daniel who in other respectsbetrays a family resemblanceto the Cividaleangels."5

In the primitiverelief carvingof this altar, it is not

easy to say what representscostume ornamentand

what is ornamentalstylizationof folds. But a connection with the claviseemsto me possible.

EarlierI had noted the occurrenceof the clavuson

the thighin imagesof Lombardkingsin a manuscript

of laws in La Cava (Badia Ms 4), apparentlycopied

from a model of the ninth century."0

This suggested

the possibleoriginof the motif in royalcostume.It is

not at all characteristic

of the dressof Byzantineor

Carolingianrulers,though it does appearon the costume of kingsand crownedMagi in Ottonianart. In

Castelseprioand in Carolingianworks the clavus is

found more particularlyon the thighsof angels. But

in drawingsof the ninthcenturyin a nativemanuscript

in Vercelli(BibliotecaCapitolareMsCLXV,Canonsof

Councils)"6the clavus, decoratedwith dots or beads

is appliedjustbelowthe knee on enas in Castelseprio,

throned figures whose foreshortenedthighs are not

visible;theseare the emperorsConstantineand TheodosiusII (Fig. I1).Y2 Here one may assume,I think,

thatthe bandbelowthe kneehasbeentransferredfrom

the thigh. The transverseclavusin this manuscriptis

not limited to the emperors;two seatedclericsat a

What makesthese

councilwear the sameornament."6

for

even

more

interesting the problemof

drawings

that

in one of the miniatures(Fig.

Christ

is

Castelseprio

linearrays crossing

nail-headed

with

a

nimbus

has

7)

the circle."'All the thronesare of the simpleblock

type that appearsin the paintingof the Hetoimasiaat

Castelseprio.The drawingsin this manuscriptshow

that several distinctivemotifs of the frescoesexisted

elsewherein Lombardyin the ninthcentury.

It may be arguedthat the two elementsconsidered

in these notes-the rayedcrossnimbusand the thigh

band-occur in Ottonianas well as Carolingianart,

and that the presentstudy thereforepointsonly to a

probableterminus post quem for Castelseprio:the fres-

coes are not earlierthan the eighth centuryand may

well be of the tenth. If I inclineto the view that the

50o.The formhad alreadyreachedthe Northin the second 57. A. Haseloff, Pre-RomanesqueSculpturein Italy, New

half of the eighth centuryin late Merovingian art; it appears York (1930 ?), pls. 48-50, and articles by Hj. Torp and

clearly in a manuscriptof Corbie,Paris, Bibl. Nat. lat. 11627, L'Orangein the Atti del 2o Congressointernazionaledi studi

fol. iv (E. H. Zimmermann,VorkarolingischeMiniaturen, sull' alto medioevo, Spoleto, 1953.

Berlin, 19x6-x9x8, plates, vol. II, pl. 109).

58. C. Cecchelli, I monumentidel Friuli del secolo IV all'

I, p. 9, fig. 5 (StadtbibliothekXI.

51. Die Elfenbeinskulpturen,

MS 3x, fols. 5, 6, 9, x7, etc.). On this manuscript see also W.

Neuss,Die Apokalypsedes HI. Johannesin der altspanischen

Miinster(Westphalia),

Bibel-Illustration,

und altchristlichen

I, Cividale, Milan and Rome, 1943, A

pl.

.

59. Koehler, op.cit., fig. 8.

60. ART BULLETIN, XXXIV, 1952, p. i6o.

6x. See Gabrielli, op.cit. (note 33 above), pp. 303, 304,

pls. CLVIII,CLIx. The author dates the manuscript in the last

1931 , I, 248ff.

52. See Neuss, op.cit., pp. 248, 249.

quarterof the eighth century,but the script points to the ninth.

62. This detail does not appearon ecclesiasticalor imperial

dress in the painting of a council under Theodosius I (362)

54. Ibid., I, pl. x (the angel of the Annunciation).

55. For the most recent views, see W. F. Volbach, "Ivoires in Paris, Bibl. Nat. MS gr 51o (Omont, Manuscrits grecs

mosans du Haut Moyen Age originaires de la region de la de la Bibliothdquenationale, pl. L).

Meuse," in L'Art mnosan(Journkesd'etudes, Paris, February,

63. Gabrielli,loc.cit., pl. cLxIII (Council of Constantinople,

53. Reproducedby Goldschmidt,loc.cit.

1952),

43-46.

56.

Recueil prepare par P. Francastel, Paris, 1953, PP.

ART BULLETIN,

XXXIV,

1952,

pp. I53,

154.

381).

64. Ibid., pl. cLxII.

NOTES

299

(Figs. 1-3). This is probably the chief reason why

the pane has been overlooked for nearly a hundred

years. The window in questionis the first from the left

of the three windows in the middle choir chapel and

the pane is the first on the.left in the second row from

the bottom. Another reason why it has not been

noticed is the difficulty of gaining access to it from

the outside. If one obtainspermissionto enter the little

garden, however, one can clearly see from the patina

which of the panes are original. But it is also possible

to see from the inside, in the ambulatory,that the pane

and the tendril band to the left of it are old, since they

After this paper was written, I observedwhat appearsto be are darker in color than the rest of the

glass (Fig. 2).

the motif of the transverseclavus on a work of the sixth cen- No one will

the fact that these portions are

question

It

is

the

set

of

of

the

that

originally

fragments

ivory panel

tury.

formed the counterpieceof the leaf of the Murano diptych ancient. The theory that while the glass is old the denow in Ravenna. (See W. F. Volbach, Elfenbeinarbeitender sign is new, and that the whole pattern is rearrange,

is untenable because the faces of the two women and

Spdtantikeand des frfiken Mittelalters, 2nd ed., Mainz, 1952,

p. 65, nos. 127-129, pl. 39, 4o, 45.) The thigh band is most the lines on their garments are different and very

evident and most like the form in Castelseprioon the figure much better in

quality than those elsewhere in the

of Saint Anne (in the fragmentin the Hermitagein Leningradsame

window.

Volbach, no. 129, pl. 40). But this detail belongs to the painted

The design represents two women without halos,

ornamentationof the ivory panel together with the gold stars

on the background.Although the painting is old, there re- both facing right and each with her right hand pointing

mains a doubt concerning its age; we are not sure that it is

(Fig. I). A little above knee height are letters

of the sametime as the carving.The motif of the applique upward

of

which

a capitalS is legible on the left and a capitalC

thighbandis not foundin plasticformin otherworksof the

samegroup or schoolof ivory sculpture.Yet on one of the on the right. Above the letters following the S is a confragmentsof the same diptych(formerlyin the Stroganoff traction sign. The first of the small letters is perhapsan

Collectionandnow in privatehandsin Paris) representing

the i, followed by what may be a b cut off by the new

the Trial by Waterand the Journeyto Bethle- lead. This

Annunciation,

portion of the inscription may be read as

hem, of which the last two are uncommonthemes and

"Sibylla."

Following the C on the right is an illegible

with some remarkable

similarities

occur also in Castelseprio

in the Journey(Volbach,no. 128,pl. 45), there letter, perhaps a v with the remains of a contraction

of conception

as the thigh bandin sign above it. The C may probablybe construed as the

are incisedlinesthat may be interpreted

question,unlesstheyare, as Dr. Volbachsupposes(in a letter beginning of Cumae.'

to the writer), simplyschematicgroovesrepresenting

folds;

The two sibyls are standing against a blue backthe photographsare not clear enough to permita definite

ground in an architectonicframe. A pointed clover-leaf

judgment.

arch rests on slender red shafts and is surmounted

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY

by a yellow Gothic gable with crockets and (restored)

finial which cuts across a horizontal gallery of six

yellow tracery windows. On either side of this Gothic

UNNOTICED FRAGMENTS OF

frame are green frontal buttresses and two lateral

in profile. Each buttress is made up of four

buttresses

OLD STAINED GLASS IN

segments separated by Gothic cornices. Blind tracery

NOTRE-DAME DE PARIS

appears on the frontal buttresses, and a pattern of

PAUL FRANKL

joints on the lateral ones.

From these two figures the nineteenth century

It may be assumedthat at the time of their construc- painterdeviseda compositionof twelve sibylsand twelve

tion (1296-1330) the east chapels of Notre-Dame in apostles (Fig. 3). The window has four axes of equal

Paris were furnishedthroughoutwith stainedglass win- breadth. In the first and fourth, a and d, he placed six

dows. These were destroyed, perhaps during the En- sibyls and in each of the two middle axes, b and c, six

lightenment or the French Revolution. When Viollet- apostles.The two lower rows contain two figures each,

le-Duc restoredNotre-Dame (i1845-1856) the chapels the two upper rows, one each. This distributionmay

were provided with new stained glass similar in style correspond to some original pattern since there are

to that of the thirteenth century. Glass paintersof this pieces of old glass above and below the section which

period liked to set into their new works bits of old glass is preservedin its entirety.2The old pane is only about

which were left over after a buildinghad been restored. half as wide as the window axis. For the apostles the

Here, however, a whole pane was employed and was painter developed a frame by adding narrow open

used as the basis for the design of the entire window arches with gables. For the sibyls he employed the refrescoes are of the eighth century, it is because their

style fits better between the classical forms of S. Maria

Antiqua and the classicismof the Carolingian schools

than between the Byzantine miniatures of the tenth

century and Ottonian art, where others have placed the

frescoes; and this earlier dating is supportedby a number of details, including the painted uncial inscriptions

which seem so much older than the inscriptionsrecording the ordination of a priest, added in the tenth century, that a palaeographerlike Lowe could date them

in the sixth century.

I. Concerning the sibyl theme, cf. Pauli-Wissowa, RealLexikon der classischen Altertumswissenschaft,2. Serie, II,

Stuttgart, 1923, cols.

2073-2183,

and Wilhelm VSge, Jdrg

Syrlin der litere und seine Bildwerke, Berlin, x95o, pp. I5ff.

2. This observation was made by Louis Grodecki, who

recognized as old three other portions of the window: in the

first and third rows in the secondaxis and a piece of tendril in

the first and second rows in the fourth axis. Elsewhere also

little fragmentsof old glass were used.

© Copyright 2026