Hyperlipidemia in Early Adulthood Increases Long

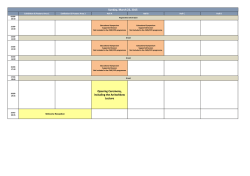

DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 Hyperlipidemia in Early Adulthood Increases Long-Term Risk of Coronary Heart Disease Running title: Navar-Boggan et al.; Hyperlipidemia in Early Adulthood Ann Marie Navar-Boggan, MD, PhD1; Eric D. Peterson, MD, MPH1; Ralph B. D’Agostino, PhD2; Benjamin Neely, MS1; Allan D. Sniderman, MD*3; Michael J. Pencina, PhD*1 1 Duke Clinical Research Institute, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC NC; 2B Boston oston t University, Boston, MA; 3Mike Rosenbloom Laboratory for Cardiovascular Research, McGill Centre, Canada University Health Cent ntre t e, Montreal, Ca ana n daa *contributed *c conttrib buteed ed equ equally quual ally y Correspondence: Address forr Co Corr rres rr espo es pond po n en nd encce: Ann Marie Navar-Boggan, MD, PhD and Michael J. Pencina, PhD Duke Clinical Research Institute Duke University Medical Center 2400 Pratt Street Durham, NC 27705 Tel: 919-684-8111 Fax: 919-668-8830 E-mail: [email protected] or [email protected] Journal Subject Codes: Atherosclerosis:[90] Lipid and lipoprotein metabolism, Ethics and policy:[100] Health policy and outcome research 1 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 Abstract Background— Many young adults with moderate hyperlipidemia do not meet statin treatment criteria under the new AHA/ACC cholesterol guidelines as they focus on 10-year cardiovascular risk. We evaluated the association between years of exposure to hypercholesterolemia in early adulthood and future coronary heart disease (CHD) risk. Methods and Results—We examined Framingham Offspring Cohort data to identify adults without incident cardiovascular disease to age 55 (n=1478), and explored the association between moderate hyperlipidemia (non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C] 160 mg/dL) CHD. At median 15-year g ) duration in early y adulthood and subsequent q y follow-up, p CHD p, rates ates were significantly elevated among adults with prolonged hyperlipidemia exposure exp xppos osur uree by aage ur ge 55: 4.4% for those with no exposure, 8.1% for 1–10 years, and 16.5% for those with 11–20 years exposure after adjustment other ex xpo posu sure r (p<0.001); (p< p<00.00 001) 1); this th his i association ass s occia iationn persisted p rssisted af pe fteer adju ust stme m nt ffor or ot the herr ca ccardiac rd dia iacc risk ffactors accto ors including non-HDL-C (HR CII 1.0 1.05–1.85 per ncllud u ing non-H HDL-C C aatt age gee 555 5 (H HR 11.39, .339, 95% 95% C 05– 5–1. 1.85 1. 855 pe er ddecade ecaadee off hhyperlipidemia). yperrli l pid pidem mia) a). Overall, Ov Over erral all, l 85% l, 85% of of young youn yo ungg adults un adul ad u tss with with prolonged pro rolo long lo nged ng ed hyperlipidemia hyp yper erli er lipi li pide pi demi de miaa would mi wou ould ld not not have hav avee been been recommended reccom omme mend me nded nd e therapy However, those for statin the era rapy py at at age age 40, 400, under u de un d r current cu urr rren entt national en nati na tion ti onnal guidelines. gui u de deli l nees. H li ow wev ever er, am er aamong ongg th on thos o e not os considered statin therapy candidates at age 55, there remained a significant association between cumulative exposure to hyperlipidemia in young adulthood and subsequent CHD risk (adjusted HR 1.67, 95% CI 1.06–2.64). Conclusions—Cumulative exposure to hyperlipidemia in young adulthood increases subsequent risk of CHD in a dose-dependent fashion. Adults with prolonged exposure to even moderate elevations in non-HDL-C have elevated risk for future CHD and may benefit from more aggressive primary prevention. Key words: hyperlipidemia; younger patients; coronary heart disease risk 2 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 Hyperlipidemia is a potent risk factor for atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease (CHD) and is present in a substantial proportion of young adults. According to data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), between 11.7% of adults aged 20–39 and 41.2% of adults aged 40–64 had elevated low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels, but only 10.6% of adults aged 20–39 and 47.7% of adults age 40–64 with hyperlipidemia were on treatment.1 The newly released American Heart Association (AHA)/American College of Cardiology (ACC) guidelines for treatment of blood cholesterol for the prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) recommend statin therapy for all adults with prevalent CVD, LDL-C 190 mg/dl, diabetes, or 10-year risk of atherosclerotic CVD 7.5%, as assessed by the new Pooled Cohort Equations.2 Although CHD events such as myocardial infarct infarction cttio ionn pr pres present esen sen entt suddenly, uddenly, the advanced extensive complex intramural lesions that lead to plaque rupture develop over ov ver decades. decad ecad ades e . Since Siinc ncee the natural history of atherosclerosis atheros oscl os cleerosis is prolonged, prolo ong n ed d, th thee risk of clinical events rises isees exponent exponentially tia iall l y la lat late te iin te n li life life. fe.. As a result, fe ressult, th the he new he w cholesterol chooleest steerool ol guidelines gui uide deli liiness led leed to to a high hig ighh number nuumb mber err of older ol lde derr adults a ul ad ults ts aged age gedd 60 60 years yeear ears to to be recommended rec ecom om mme mennded nded for for statin sta taatiin therapy, the hera rapy ra py, with py w th wi h relatively rel elat ativ at iv vel e y fewer feweer younger fe y ung yo unger ge adults meeting ng sstatin taati tinn re rrecommendation c mm co mmen en nda dati tiion o ttresholds. resh re shol sh olds ol ds.1 ds Studies on adults with familial hypercholesterolemia have shown CVD risk is increased early among those with very high LDL-C levels.3 Similarly, adults with extremely low LDL-C levels conferred by genetic polymorphisms have significantly lower than average risk of CVD.4,5 However, the association between prolonged exposure to mild to moderately elevated lipid levels in young adulthood on an individual’s subsequent risk of CHD has not previously been well described.6 Therefore, we used the Framingham Offspring Study to address the impact of duration of hyperlipidemia in young adulthood (ages 35 to 55) and future risk of CHD beyond age 55 years. 3 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 Methods Study Design and Sample Our study examined data on 5124 individuals from the Offspring Cohort of the Framingham Heart Study recruited between 1971 and 1975.7 In order to identify participants with sufficient observation time to evaluate both the number of years of exposure to hyperlipidemia, as well as the person’s future risk of CHD, participants were eligible for inclusion in this analysis if: 1) they had attended Offspring Cohort examination 4 (1987-1991), 5 (1991-1995), or 6 (19951998); 2) were between the ages of 53 and 57 years; and 3) were free of CVD (defined as myocardial infarction, angina, coronary insufficiency, transient ischemic attack, stroke, coronary heart disease death, cardiovascular death, intermittent claudication, or heart failu ure8) at at tthe he ttime ime im failure of eligibility assessment. Of exams 4, 5, and 6, the exam closest to age 55 was used as the “baseline” “b bas asel elin el ine” in e” visit. vis isit. Data Data Da t from prior exams were use used ed tto o evaluate thee nu nnumber mbeer mb er of years of hhyperlipidemia hyp yperlipidemia pe ia aattained tttaine need by by tthe he bbaseline assel elin inee aage. ge.. T This his resulted reesullteed in in a ssample ampl am plee of 11478 4788 ad 47 adults dul u ts ffree reee of CVD who were approximately years Participants were CV VD at a tthe hee bbaseline aseelin as ne eexamination, xamin aminat a io at on , w hoo w eree ap er appr prox pr oxiimate ox tely te ly 555 5 ye year arss ooff aage. ar g . Pa ge art rtic iccip ipan ntss w erre then hen prospec prospectively ctiive vely ly ffollowed o lo ol lowe weed fo fforr up to to 20 yyears ears ea rs ffor or tthe he development dev evel elop el opme op mentt ooff CH me CHD D (m (myocardial myo yoca card ca r ial rd infarction, angina, coronary insufficiency, coronary heart disease death) events. Median followup was 15 years. Outcomes and Exposures The primary factor of interest was the number of years of exposure to hyperlipidemia in the 20 years prior to the baseline visit at age 55 (e.g., number of years of elevated non-high-density lipoprotein cholesterol [HDL-C] between ages 35 and 55). Consistent with the lipid measures used in the newest Pooled Cohort Equations, hyperlipidemia in our primary analysis was defined based on non-HDL-C, with levels 160 mg/dL considered elevated. This level is equivalent to 4 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 the 70th percentile of the American population according to NHANES. Since Framingham Offspring examinations occur approximately every 4 years, we interpolated hyperlipidemic status in the years between the examinations. For individuals who developed hyperlipidemia in the time interval between study visits, we assumed that the date of development was midway between the two exams. For individuals with fewer than 20 years of data prior to baseline, we conservatively assumed that the participant was free of hyperlipidemia for the time period without data. For participants with missing data at any follow-up exam, the value from the prior exam was carried forward. In sensitivity analyses we also examined prior elevation of non-HDL-C as a continuous variable. Each person’s average non-HDL-C over the preceding 20 years was cal allcu cula l ted, la calculated, weighted by the number of years between exams. In addition, LDL-C, rather than non-HDL-C was evaluated was ev val alua uate ua tedd using te ussin ingg number of years with LDL-C -C 130 mg/dL. B e au ec use the Friedewald equation 130 Because w ass us uused ed to ca alc lcul u at ul atee LD DL-C, L-C, aadults du ult lsw itth trig i lyceeriidess over ig overr 400 400 mg/dL mg/ g/ddL aatt any any time tim me were we e was calculate LDL-C, with triglycerides ex xcl clud uded ud e ffrom ed rom ro m th he LD DL--C an nal alys ysis ys is.. is excluded the LDL-C analysis. Statistical Analysis An nal alys ysis ys is First, using the number of years of hyperlipidemia by age 55, adults were stratified into three groups: 1) those without hyperlipidemia by age 55; 2) those with 1–10 years of hyperlipidemia; and 3) those with 11–20 years of hyperlipidemia. Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated to evaluate the risk of CHD over the subsequent years, and the log-rank test was used to test the overall survival experience. Cox proportional hazards regression models were employed to evaluate the relative risk of increasing the number of years with hyperlipidemia on the onset of CHD events by evaluating the association between number of years of exposure to hyperlipidemia at age 55 as a continuous 5 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 variable between zero and twenty and future risk of CHD. To determine to what extent the association between duration of hyperlipidemia and CHD risk could be attributed to a worse overall health state associated with hyperlipidemia, multivariable analyses were performed adjusting for the following standard non-lipid risk factors: age, sex, systolic blood pressure (SBP), antihypertensive treatment, HDL cholesterol, diabetes, and smoking. Next, to determine if the cumulative exposure to hyperlipidemia was a marker for prevalent hyperlipidemia at age 55 or if the duration of hyperlipidemia was associated with increased CHD risk independent of lipid levels at that age, baseline (age 55) non-HDL-C level was also included in the multivariable analysis. The final multivariable model also included adjustment for lipid-lowering therapy at ratios the baseline and over the follow-up period in a time-dependent fashion. Hazard ratio os fo for th he association between duration of hyperlipidemia and future CHD risk are presented per 10-year increase. ncrrea easse. se secondary As sec con ondaaryy analyses, anaalyse lysees, s, we we repeated repeated our rep ouur primary prrim marry analysis anal an alyysis ysiss of of association asssoci as sociat attio ionn between beetw weeen years yearss of year exposure sample would ex xpo posu sure su re to to non-HDL-C non--HD nonHDL L-C 160 1660 mg/dL mg/d mg /dL /d L in i oour ur sam ampplee off yyoung am oung ou ng aadults dultts who dult who wo oul uldd no nott bee specifically pecifically rrecommended ecom ec omme om m nd me nded ed for for statin sta tati t n therapy ti ther th erap er apyy under ap unde un derr the de th he 2013 2013 AHA/ACC AHA HA/A ACC guidelines. gui uide deli l ne li nes. s.. This Thi hs excluded adults with 10-year CVD risk 7.5%, diabetes with LDL-C 70 mg/dL, or LDL-C 190 mg/dL. Next, we assessed the proportion of adults who would have been recommended for statin therapy at age 40 and age 50 under current guidelines based on diabetes status, LDL-C, and 10year CVD risk, stratified by years of exposure to hyperlipidemia (zero, 1–10, and 11–20 years of hyperlipidemia). We considered both the 7.5% and the 5% risk thresholds to determine treatment eligibility per the new guidelines. This analysis was performed to determine the extent to which individuals with prolonged hyperlipidemia would have been identified as treatment 6 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 candidates by the new guidelines during the period of exposure to hyperlipidemia. Since LDL-C was estimated using Friedewald’s equation and, therefore, unavailable in adults with triglycerides >400 mg/dL, adults with triglycerides >400 mg/dL were considered “statin eligible” in the analysis that evaluated statin recommendations. In sensitivity analysis, we investigated the robustness of our results to the choice of lipid parameter and choice of threshold. First, the association between years of exposure to LDL-C 130 mg/dL and future CHD was evaluated using multivariable Cox proportional hazards modeling. Second, to determine whether the results depend on the 160 mg/dL non-HDL-C threshold, the association between the weighted average non-HDL-C over the prior 20 years and points future risk of CHD was evaluated using restricted cubic splines. Inflection point ts in n tthe he ggraph, raph ra ph,, ph rounded ounded to the nearest 5 mg/dL non-HDL-C were identified and then used as cut points in a piecewise pi ieccew ewiise ise linear line li nearr model mod o el of prior average non-HDL-C non-HD DL-C C and future CHD CHD H rrisk. iskk. Cox proportional is hazards increase hazard haza ar s modeling modeeli linng was wass performed per erfo form fo rmed rm ed evaluating eval valuatingg the the impact im mpacct ct of of each each 10 10 mg/dL mg/d mg / L in /d ncrea crease se iin n ave aaverage verag erag ge prior elevation risk prio pr iorr el io elev evat atio at ionn ooff nnon-HDL-C io on-H on -H HDL DL-C -C C aand nd ffuture utuure ut ure ri ris sk ooff CH sk CHD, D, aadjusting djuusti dj ting ti ng ffor or tthe he ssame am me ch ccharacteristics araacteerisstic ar sticss at at treatment, smoking, baseline as inn the the h primary pri rima mary ma r analysis ry ana naly ysi siss (age, (age (a gee, sex, sex, x SBP, SBP, P antihypertensive ant n ih hyp yper erte er tens te nsiv ns i e tr rea eatm tmen tm e t,, ddiabetes, en iabe ia bete be t s, smoking te g non-HDL-C, HDL-C, and lipid therapy). Finally, to evaluate the impact of including adults on lipid-lowering therapy at baseline, the primary analyses of the association between years of elevation in non-HDL-C and future CHD risk were repeated excluding adults on lipid-lowering therapy at baseline. The analysis was approved by the Duke University Institutional Review Board. All Framingham Offspring cohort participants gave informed consent for participation. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.3. 7 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 Results Study Population Characteristics of the study sample at baseline are presented in Table 1. A total of 124 individuals in the cohort developed CVD prior to age 55 and were not included in our sample. The final sample included 1478 adults free of CVD at baseline with 0-20 years of hyperlipidemia. Of these, 512 adults did not have hyperlipidemia, 389 adults had 1-10 years of hyperlipidemia, and 577 adults had 11-20 years of hyperlipidemia exposure by baseline age. Individuals with hyperlipidemia at baseline were more likely to be diabetic, male, and smokers, and had higher SBP, body mass index, total cholesterol levels, and lower HDL-C levels than those hose without hyperlipidemia. Only 85 patients overall (5.8%) were on lipid-lowering lipid-low werin in ng treatment trea tr eatm ea tmen tm ent at the baseline visit. Years and Risk of CHD Year Ye arss of Hyperlipidemia ar Hyp yperrli lip pi pidemia During follow-up, 155 D urring rin followw-up upp, 15 55 individuals in ndi divi vidu vi dual du alss dev ddeveloped evel velopeed new w onset onseet CHD, CH HD, D, with witth 136 1336 events even ev entts en ts by by median median med follow-up years. Kaplan-Meier CHD baseline fo oll llow ow-u ow -upp of 1155 ye year ars. s. Figure Figure Figu ree 1 ppresents rese re sen ntss Ka Kapl lan a -M Mei e er C HD eevent vent rrates vent attes ffrom ro om ba base selline se nee uup p to o 115 5 follow-up stratified hyperlipidemia years of follo oww up aamong m ng mo n ppatients atie at ient ntss st nt stra rati tifi ti fied fi ed by tthe he nnumber um mbe berr of yyears e rss ooff hy ea hype perl pe rlip ipid ip idem id emia em i at ia baseline. A dose-response pattern is seen, with progressively increasing risk of CHD as the number of years of exposure to hyperlipidemia increases (log-rank test p<0.0001). At 15 years, adults with 11–20 years of hyperlipidemia at baseline had an overall CHD risk of 16.5% (95% CI 13.5–19.9%), compared with 8.1% (95% CI 5.5–11.7%) for adults with 1–10 years of hyperlipidemia, and 4.4% (2.9–6.6%) for those without hyperlipidemia at baseline. The unadjusted risk of CHD doubled for every ten years of exposure to hyperlipidemia (Table 2, univariable HR 2.0, 95% CI 1.63–2.45 per decade of hyperlipidemia); this association was attenuated, but remained statistically significant after adjusting for other standard risk 8 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 factors including sex, age, SBP, antihypertensive therapy, smoking status, HDL-C, and diabetes (adjusted HR 1.49, 95% CI 1.20–1.87 per decade of hyperlipidemia). In addition, the association remained statistically significant after also adjusting for non-HDL-C at baseline (adjusted HR 1.39, 95% CI 1.05–1.85 per decade of hyperlipidemia), suggesting that previous cumulative exposure to hyperlipidemia is associated with increased risk of CHD later in life, independent of the cholesterol level at age 55. This association also remained significant after adjusting for lipid-lowering therapy use at baseline and follow-up. Statin Recommendations Under Current Guidelines The number of participants who would be specifically targeted for statin therapy according to the statin Off 57 tatin benefit groups as identified by the new guidelines was calculated (Table 33). ). O 5777 adults adul ad ults with 11–20 years of hyperlipidemia at the index age of 55, 87 (15.1%) participants would have met criteria met cr rit iter eria ia ffor or sstatin tati ta t n therapy at age 40, and 2011 ((34.8%) ti 344.8%) would hhave a e me av mett criteria at age 50. These Theese es numbers numberrs were we e lower low wer among amo mong ng g those tho hose see with witth 1–10 1–110 years year arss of ar of hyperlipidemia hyp yper erli lipi piide d miaa at at age age 55: 55: off 389 389 adults, (1.8%) would criteria statin would ad dul u ts ts,, 7 (1 (1.8 .8%) .8 %) w oulld hhave ou ave me av mett cr crit iter erria ffor or sta tattin ta n ttherapy herrapy aatt ag agee 40 aand nd 444 4 (1 ((11.3%) 1 3% 1. %) w ould uld hav hhave ave ve met criteria at at age age 50. 50 When W en we Wh we used u ed the us the h lower low ower er risk riiskk threshold thr hres esho es hold ho ld proposed pro ropo pooseed by tthe hee gguidelines uide ui deli de l nes (10li year CVD risk 5%) to identify adults eligible for statin therapy, 25.1% of adults with 11–20 years of hyperlipidemia at baseline would have been recommended for statin therapy at age 40, and 51.6% would have been recommended for statin therapy at age 50. When we restricted our analyses to those adults not recommended for statin therapy at age 55 (i.e., 10-year CVD risk below 7.5%, LDL-C <190 mg/dL, and no diabetes with LDL-C 70 mg/dL; n=971), the association between hyperlipidemia and risk of CHD was preserved; adults with both 1–10 and 11–20 years of hyperlipidemia at baseline had significantly higher rates of CHD compared with adults without hyperlipidemia (Figure 2, p<0.001). In 9 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 multivariable models adjusting for standard risk factors and non-HDL-C at baseline, each decade of hyperlipidemia at baseline was associated with a 67% increased risk of CHD at follow-up (Table 2, HR 1.67, 95% CI 1.06–2.64, p=0.03). Sensitivity Analyses Using an LDL-C level of 130 mg/dL rather than non-HDL-C 160 mg/dL as the primary exposure yielded similar results (appendix table 1). The results based on average prior nonHDL-C are shown in Figure 3, where they are plotted against future CHD risk approximated using a restricted cubic spline and a piecewise linear model. The effect of weighted non-HDL-C below 125 mg/dl on CHD was non-significant, suggesting that individuals below this cut-point the effect of weighted above all have similar (lower) risk of CHD. Similarly, a weighted non-HDL-C non-HDLL--C ab bov ovee 19 1955 this cut-point all have mg/dl on CHD was non-significant, suggesting that individuals above a similar weighted imi mila larr (high) la (hig (h igh) ig h) risk rissk of o CHD. The association between betw wee eenn average weig ig ghted ed d nnon-HDL-C on-HDL-C between mg/dL and wass st statistically Cox modeling, 1125–195 25–195 5– mg/d dL an nd CH CHD D wa w stat atis at issti t ca callly ssignificant. iggnifficaant.. IIn n Co C oxx pproportional ropor orti tionnal hhazards ti azards azar ds m odel od elin el ing, n , every mg/dL mg/dL the preceding ev ver eryy 10 1 m g/dL g/ dL iincrease ncreas ncre asee in aaverage vera ve rage ra ge nnon-HDL-C on-H on-H -HDL DL-C DL -C C bbetween etween etw ween 1125–195 255–1 – 955 m g/ddL dL oover verr th ve he pr pre eceedin edin ng 20 2 years was associated asssooci c atted with wit i h a 33% 3 % increase 33 i cr in c eaase in in future futu fu t re CHD tu CHD D risk ris iskk (HR (HR per per 10 mg/dL mg/ g/dL dL increase inc ncre r ase 1.33, re 95% CI 1.23–1.45, p<0.001). After adjusting for standard risk factors including baseline nonHDL-C and lipid therapy at baseline and follow-up, this association remained statistically significant (HR 1.20, 95% CI 1.08–1.35, p=0.001). Finally, excluding adults on lipid-lowering therapy at baseline did not result in substantive changes to the results (appendix table 2). Discussion In this analysis of adults free of CVD at age 55 in the Framingham Offspring Study, we found that those with the longest prior exposure to moderately elevated non-HDL-C had a nearly four- 10 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 fold increased rate of CHD at follow-up. Importantly, not only does prevalent hyperlipidemia increase future risk of CHD, but the length of exposure to hyperlipidemia in the fourth and fifth decades of life affects future CHD risk in a dose-responsive manner as the association between exposure to hyperlipidemia in young adulthood and future CHD remained highly significant even after adjustment for non-HDL-C at age 55. This association was preserved in individuals without direct recommendations for statin therapy under the current guidelines. These findings are aligned with the biological understanding of atherosclerosis as a progressive disease due to ongoing vessel injury over time—a substantial part of which is caused by elevated cholesterol levels.6 In addition to the 10-year risk, which was calculated using the Pooled Coh Cohort ohhorrt Eq Equa Equations, uati ua tion ti o s,, on the he current AHA/ACC cholesterol guideline recommends when making treatment decisions to consider co ons nsid ideer id er family fam amiily history, hisstory, hi st C-reactive protein, coro coronary ona n ry artery calciu calcium, um, m aankle nklle brachial index, and nk lifetime Our suggests sustained moderate lipid levels ifettime ti CVD rrisk. isk.. O is ur ddata ataa su at sugg gges e ts es ts tthat haat su usttaineed mo odera deraatee eelevation leevati tion onn ooff li ipi pidd le eve vels ls aalso lsso confers substantial future Given association duration co onf n er erss a su ubs b ta tanntiial ial rrisk iskk ooff fu futu tu ure eevents. vent ve n s. nt s. G iv ven e tthe hee ppotent otten entt as sso s ci c at atio i n betw io bbetween etw weeen du dur ratiionn ooff hyperlipidemia mid-adulthood future CHD should exposure to hy hype perl pe rlip rl ipid ip id dem emia iaa bby y mi midd-ad a ul ulth th hoo oodd an andd fu utu ture re C HD rrisk, i k, cclinicians is l ni li nici cian ci a s sh an hou ould ld d also consider lifestyle intervention or even treatment for adults with prolonged prior exposure to hyperlipidemia. Randomized controlled trial evidence support the clinical benefit of statin therapy for primary prevention in adults in this age group, with a number of primary prevention trials demonstrating that statins initiated in midlife significantly reduce future clinical events.9-11 While the new guidelines identify those patients with a very high lipid level on a single measurement (LDL-C 190 mg/dL) as candidates for statin therapy, they do not further differentiate risk in others based on lipoprotein levels. Under current guidelines, only one in six adults in this cohort with prolonged duration of exposure to hyperlipidemia would have been 11 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 directly recommended for statin therapy at age 40, and one in three at age 50. By design, our analysis cannot answer the question whether early statin intervention in those on the hyperlipidemic trajectory would decrease their future CHD risk. When to initiate treatment in adults with moderately elevated non-HDL-C in early adulthood remains unknown. There are no studies evaluating the long-term effectiveness of statin therapy in adults aged 30–50 with only moderately elevated lipid levels and without other risk factors. Furthermore, initiating statin therapy at younger ages would result in a much longer duration of statin use than has been studied in randomized trials. This lack of knowledge further stresses the need for additional research focused on the safety and efficacy of long-term statin use in early and middle adulthood too reduce cardiovascular disease later in life. This analysis also highlights the fact ctt tthat h t ri ha risk sk prediction models focused on a 10-year horizon may underestimate the contribution of prolonged exposure ex xpo posu sure su re to to chronic c ro ch oni nicc disease, and the need to continue cont ntin nt inuue to evaluatee how h w to best ho best incorporate 30-year 12, 13 riskk estimates or lifetime lifetime if esttim imat ates ess into into nto current cur urre rennt re nt prevention preevenntiion guidelines. guideeli gu eliness.12, Limitations Li imi mita tati ta tion on ns and and Stre S Strengths treenggth ths Our analysiss has has several sev ever erral limitations. lim im mit itat atio ions io ns.. First, ns Fiirs r t, we we only o ly included on in ncl clud uded ud ed adults adu dult l s aged lt aged 53–57 53–5 53 –577 who who were w re free off we CVD; therefore, the point estimates cannot be extrapolated outside of this age range. Nevertheless, we believe that this analysis demonstrates the long-term impact of hyperlipidemia in young adulthood. Second, our analysis defined hyperlipidemia using a non-HDL-C cutoff of 160 mg/dL, which is consistent with how the prior Adult Treatment Panel (ATP) III guidelines defined elevated cholesterol; given that the risk of CHD events expands with increasing levels of non-HDL-C, the use of this or any cut-point may have falsely dichotomized a continuous relationship. However, using a continuous approach which averaged non-HDL-C over the preceding 20 years yielded similar results, showing that the risk associated with exposure to non- 12 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 HDL-C increased linearly between 125–195 mg/dL. However, the number of individuals with prior average non-HDL-C below 125 mg/dL and above 195 mg/dL is low. Therefore, we cannot definitively determine if the relationship between prior average non-HDL-C and future CHD continues below 125 mg/dL or above 195 mg/dL. Third, this analysis only considered the duration of hyperlipidemia and not the duration of all other risk factors and comorbidities. While the presence of comorbidities was accounted for at age 55, it is likely that the duration of certain comorbidities, such as diabetes and hypertension, may also affect future CHD risk in a similar duration-dependent manner, as demonstrated in this hyperlipidemia analysis.14 Next, our study design excluded 124 individuals with premature CVD before age 55, representing 8% of the initial nitial sample. As a result, some individuals at highest risk, due to hyperlipidemia hyperlipidemi miaa at a young you oung ng age, age g may have been excluded; these exclusions would have led to an underestimation of the association asssooci ciat atio at ionn between io betw be wee eenn duration of hyperlipidemia aand ndd CHD risk. Notably, Notablly, our ouur ur study study dy also als lsoo had haad several sevver se veral strengths. strrenggth hs. First, First, Fir rst,, oour ur aanalysis naly lysi sis iiss bbased si assed oon n th thee Framingham Heart before widespread Fram Fr amin am ingh in g am H gh eartt Study Stu udy data datta collected coll co llec ll ectted ed iin n aan n eera r be ra efore ore wi wide deesp s read read sstatin tatiin use, tati use, e aallowing lllow owin ng us tto o evaluate the impact imp mpac acct of untreated unt n re reaate t d hyperlipidemia. h pe hy p rllip ipid idem id emia em iaa. No Nott on only nly w was ass tthe h ooverall he vera ve rall ra ll rrate a e of llipid-lowering at ipid ip i -lowering id therapy in this group low, but the risk associated with increased duration of hyperlipidemia remained significant even after adjusting for lipid-lowering therapy at baseline and follow-up and excluding adults on lipid lowering therapy at baseline. Second, due to the length of followup, the Framingham Offspring data allows for accurate, longer-term assessment of risk factors, as well as follow-up of hard cardiovascular endpoints. Our analysis fully utilizes the consecutive follow-up, as well as risk factor and event ascertainment, during the course of 35 years (20 years of potential exposure and 15 years of follow-up), which is uniquely available in Framingham. Finally, our study design eliminates the possibility that the association seen between duration of 13 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 hyperlipidemia and risk of coronary events is a result of residual confounding by age, as risk was calculated for all participants starting around age 55. Conclusions We conclude that the exposure to hyperlipidemia in the fourth and fifth decades of life is associated with a substantially increased risk of CHD in a dose-responsive fashion, even among adults otherwise predicted to have low risk of CVD. Our findings suggest that adults with longstanding moderate elevations in non-HDL-C should be added to those already identified by the current guidelines as candidates for an informed patient-physician discussion about appropriate lipid management strategies to reduce future risk of heart disease. Acknowledgments: thank Ackn kn now owle ledg le dgme dg ment nts: nt s The authors would like to th han ank Erin Hanley, MS, S, ffor o her editorial or contributions Ms.. Ha Hanley receive compensation contributions, co onttri ribu b tionns to o tthis h s manuscript. hi maanuusc s ri ript pt.. Ms pt M Hanl nley ey y ddid id nnot ot rec ecei eive ei ve com om mpe pens nsat attio i n fo forr he herr co cont ntri ribu ri buuti tion ons, apart employment where this study was conducted. ap apar parrt from her emp mploym mp yment at tthe ym h iinstitution he nstiitu ns utionn w herre re thi is st stud udyy wa as cond ducteed. Funding work supported internally Clinical Fund Fu ndin nd ingg Sources: in Sour So urce ur ces: ce s: Th This is w orkk wa or wass su supp ppor pp orte or tedd in te inte tern te rnal rn ally al ly bby y th thee Du Duke ke C lini li nica ni call Research ca Rese Re sear se arch ar ch Institute Ins nsti titu ti tute tu te in in addition Healthcare Research Quality. addi ad diti tion on to to grant gran gr antt number numb nu mber er U19HS021092 U19 19HS HS02 0210 1092 92 from fro rom m the the Agency Agen Ag ency cy ffor or H ealt ea lthc hcar aree Re Rese sear arch ch aand nd Q uali ua lity ty The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Framingham Heart Study is conducted and supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) in collaboration with Boston University (Contract No. N01-HC-25195). This manuscript has been reviewed by Framingham Heart Study Investigators for Scientific content and consistency of data interpretation with previous Framingham Heart Study publications. Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Navar-Boggan has no relevant conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Peterson has received funding for research grants from Eli Lilly and Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and funding for serving as a consultant/participant on advisory board for Merck, Sanofi-Aventis, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, and Boehringer Ingelheim. Dr. D’Agostino has 14 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 no relevant conflicts of interest to report. Mr. Neely has no relevant conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Sniderman has no relevant conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Pencina has received funding for serving as a consultant for AbbVie. References: 1. Pencina MJ, Navar-Boggan AM, D'Agostino RB, Sr., Williams K, Neely B, Sniderman AD, Peterson ED. Application of new cholesterol guidelines to a population-based sample. N Engl J Med. 2014;370:1422-1431. 2. Goff DC Jr, Lloyd-Jones DM, Bennett G, Coady S, D'Agostino RB, Gibbons R, Greenland P, Lackland DT, Levy D, O'Donnell CJ, Robinson J, Schwartz JS, Shero ST, Smith SC, Jr., Sorlie P, Stone NJ, Wilson PW. 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2014;129:S49-73. 3. Hopkins PN, Heiss G, Ellison RC, Province MA, Pankow JS, Eckfeldt JH, Hunt Huunt nt SC. SC. Coronary Cor oron o ar on ay artery disease risk in familial combined hyperlipidemia and familial hypertriglyc hypertriglyceridemia: cerrid idem em mia ia:: a case-control comparison from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Family Heart Study. Circulation. 2003;108:519-523. 2003;1 ; 08:519-523. 4. C Cohen Boerwinkle Mosley Hobbs ohen JJC, oh C, B oeerw r in inkl klee E, kl E M osle os leyy TH le TH,, Jr Jr.,.,, H obbs ob bs HH. H.. Sequence Seq equeenc ncee variations vari va riat a ions at ns in in PCSK9, P SK PC SK9, 9, low low LDL, protection coronary disease. LDL L, and prote tect ctio on aagainst gai ains ai nstt co ns oro rona nary na r hheart ry eart di iseasse. se. N Engl Engl J Med. Med ed. 22006;354:1264-1272. 0066;3554: 00 4:12 1264 64-1 64 -127 -1 272. 27 2. 5.. Ference Ferren e ce BA, BA, A, Yoo Yoo oo W, W, Alesh Alessh I, Al I, Mahajan Mah ahaj ajan aj an N, N, Mirowska Miro Miro owskka ka KK, KK, Mewada Mewad ewad adaa A, A, Kahn Kahn ahn J,, Afonso Afonnsoo L, Williams Will llia iams KA KA Sr, Sr Flack Flac Fl ackk JM. JM Effect Effe Ef fect ct of long-term long ng-t -ter erm m exposure expos osur uree to lower low ower er low-density low ow-d - en ensiity y lipoprotein lip ipoppro rotein in cholesterol be beginning early life the coronary egi ginn nnnin ingg ea arlyy in n li ife oon n th he ri risk sk ooff co coro ro ona nary ry heart hea eart rt disease: dis i ea ease se:: a Mendelian se M nd Me ndel elia el iann ia randomization analysis. Coll Cardiol. and ndom omiz izat atio ionn an anal alys ysis is J Am C olll Ca ol Card rdio ioll 22012;60:2631-2639. 012; 01 2;60 60:2 :263 6311-26 2639 39 6. Sniderman AD, Furberg CD. Age as a modifiable risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Lancet. 2008;371:1547-1549. 7. Feinleib M, Kannel WB, Garrison RJ, McNamara PM, Castelli WP. The Framingham Offspring Study. Design and preliminary data. Prev Med. 1975;4:518-525. 8. D’Agostino RB, Vasan RS, Pencina MJ, Wolf PA, Cobain M, Massaro JM, Kannel WB. General cardiovascular risk profile for use in primary care: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2008;117:743-53. 9. Downs JR, Clearfield M, Weis S, Whitney E, Shapiro DR, Beere PA, Langendorfer A, Stein EA, Kruyer W, Gotto AM Jr. Primary prevention of acute coronary events with lovastatin in men and women with average cholesterol levels: results of AFCAPS/TexCAPS. Air Force/Texas Coronary Atherosclerosis Prevention Study. JAMA. 1998;279:1615-1622. 15 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 10. Barringer TA 3rd. WOSCOPS. West of Scotland Coronary Prevention Group. Lancet. 1997;349:432-433. 11. Nakamura H, Arakawa K, Itakura H, Kitabatake A, Goto Y, Toyota T, Nakaya N, Nishimoto S, Muranaka M, Yamamoto A, Mizuno K, Ohashi Y; MEGA Study Group. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with pravastatin in Japan (MEGA Study): a prospective randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2006;368:1155-1163. 12. Pencina MJ, D'Agostino RB, Sr., Larson MG, Massaro JM, Vasan RS. Predicting the 30-year risk of cardiovascular disease: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation. 2009;119:3078-3084. 13. Berry JD, Liu K, Folsom AR, Lewis CE, Carr JJ, Polak JF, Shea S, Sidney S, O'Leary DH, Chan C, Lloyd-Jones DM. Prevalence and progression of subclinical atherosclerosis in younger adults with low short-term but high lifetime estimated risk for cardiovascular disease: the coronary artery risk development in young adults study and multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2009;119:382-389. 14. Vasan RS, Massaro JM, Wilson PW, Seshadri S, Wolf PA, Levy D, D’Agostin D’Agostino inoo RB RB.. Antecedent blood pressure and risk of cardiovascular disease: the Framingham H Heart Study. eaart r S tudy tu dy.. dy Circulation. 2002;105:48-53. 16 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 Table 1. Characteristics of Participants Stratified by Years of Hyperlipidemia at Baseline.* Variable Age Female Smoking Diabetes etes BMI Treatment ment for cholesterol Treatment ment for BP Systolic lic BP Total choles cholesterol este t ro rol HDL-C -C C cholesterol chol ch oles ol e tero rol ol Non-HDL-C H LHD LC Total (n=1478) 55 (54,56) 791 (53.5%) 281 (19.0%) 95 (6.4%) 27.0 (24.2,30.3) 85 (5.8%) 282 (19.1%) 127 (115,137) 209 (184,233) 48 (40,60) 1588 (132,184) 15 (132 (1 32,1 , 84 ,1 84)) Duration of Hyperlipidemia at Baseline 0 Years 1-10 Years (n=512) (n=389) 55 (54,56) 55.0 (54,56) 336 (65.6%) 241 (62.0%) 89 (17.4%) 64 (16.5%) 19 (3.7%) 23 (5.9%) 25.4 (23.0,28.6) 26.9 (24.5,30.1) 3 (0.6%) 10 (2.6%) 59 (11.5%) 73 (18.8%) 123 (112,134) 126 (115,136) 182 18 82 (166,199) (166 (1 6 ,199) 2155 (199,236) ( 99 (1 9 ,236) 57 (46 (46,70) 4 ,70) 499 ((39,60) 3 ,60) 39 125 (109,140) 12 (109 10 ,140 40)) 165 16 65 (148,181) (148 (1 4 ,181 81)) * Binaryy data dat ata ta presented as n (%), (%) % , co ccontinuous ontin tin inuo u uss variables var aria i bl ia bles ess ppresented rese es nt nted ed aass me m median dian n (interquartile (in interqua u rt rtile range) raange) ge) BMI indicates ndicate ates body mass index; i de in dex; x B BP, P, bblood lood lo d press pressure; sur u e; e HDL-C, HDL DL-C L-C C, high high-density g -d -density ty lip lipoprotein i oprote o in n ccholesterol hole ho ole lest ster erol o 17 11-20 Years (n=577) 56.0 (54,56) 214 (37.1%) 128 (22.2%) 53 (9.2%) (9. 9.2% 2%) 288.33 (25.4,31.0) 28.3 (25 5.44,3 , 1. 72 ((12.5%) 122.5 .5%) 5%) 150 (26.0%) 130 (119.0,140.0) (119.0,140 230 (207,253) (207,253 43 (37,51) 1833 (163,205) 18 ( 63 (1 63,2 ,205 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 Table 2. Future Risk of CHD Per Decade of Hyperlipidemia Experienced by Age 55 in Univariable and Multivariable Analyses. All Adults (n=1514) Model Univariable: duration of hyperlipidemia Duration tion of hyperlipidemia + standard risk factors at baseline† Duration tion of hyperlipidemia + standard risk factors† + non-HDL-C at baseline Duration tion of hyperlipidemia + standard risk factors† + non-HDL-C at baseline + lipid lowering therapy at baseline and follow-up HR Per Decade of Hyperlipidemia (95% CI) 2.00 (1.63-2.45) 1.49 (1.20 - 1.87) 1.39 (1.05 - 1.85) <0.0001 0.0004 0.022 1.40 (1.05 - 1.87) 0.024 * p-value Not Recommended for Statin Therapy at Baseline* (n=971) HR Per Decade of p-value Hyperlipidemia (95% CI) 1.99 (1.44-2.75) <0.0001 1.77 (1. (1.26 .26 - 22.48) .48) .4 8) 0.001 0.0 1.67 ((1.06 1.06 1. 06 - 22.64) .664) .64) 0.026 0.0 1.60 (1. (1.00 1 00 0 - 2.56) 2.56) 56) 00.048 0. 0 10-year ar predicted CVD risk <7.5%, no diabetes and LDL-C 70, and LDL-C <190 Standard ard rrisk iskk fa is fact factors: ctor ct o s: ssex, or ex x, age, e,, bblood l od lo o pressure, HDL-C, antihypertensive treatment, treatme ment nt, sm nt ssmoking, oking, diabetes CHD indicates cardiovascular ndi dica cate ca tess coronary te corona co nary ary heart heartt disease; dis isea e se ea s ; CI, confidence interval; CVD, cardiovasc scul u arr disease; HR, hazard ratio; ul rat a io; LDL-C, LDL LD DL-C, L-C low-density t lipoprotein cholesterol; cholesterol All other abbreviations can found Table abbr ab b evia br viati tion o s ca an be fou und iin n Ta T blle 1.. † 18 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 Table 3. Statin Recommendations at Age 40 and 50 for Adults With and Without Hyperlipidemia at Age 55. * Variable 0 years (n=512) 1-10 years (n=389) 11-20 years (n=577) Recommended for Statin Therapy, ASCVD Risk 7.5% Age 40 Age 50 3 (0.6%) 7 (1.8%) 87 (15.1%) 16 (3.1%) 44 (11.3%) 201 (34.8%) Recommended for Statin Therapy, ASCVD Risk 5% Age 40 Age 50 6 (1.2%) 11 (2.8%) 145 (25.1%) 43 (8.4%) 77 (19.8%) 298 (51.6%) * Based on 2013 AHA/ACC Cholesterol Guidelines. Adults with triglycerides >400 mg/dL considered statin recommended. + ACC indicates American College of Cardiology; AHA, American Heart Association; ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease Figure Legends: Figure Fi igu gure re 11.. T Time ime to im to D Diagnosis iagnosis of CHD by Numbe Number er of of Years of Hy Hyperlipidemia ype p rlip ip pide id demia at Baseline. This figure fiiguure r shows Kaplan-Meier Kap a lann Me Meie ierr curves ie curv cu rvees of of future futu fu turee risk riisk of of CHD CH HD beginning b ginn be ginn nin ng at age ag ge 55 (age (ag ge range r ng ra ngee 53–57), 53–5 53 –57), –5 stratified experienced 55. Log-rank p-value <0.0001. tra rati tiifi f ed by by years year ye arrs of hyperlipidemia hyp per erlip ip pid dem emia ia exp xper xp erie iennced byy age ie age 55 5. Lo Log g-rrank rank n p-valluee < -val 0..00 0011. *C *CHD HD indicates ndi dicattes coro di coronary rona nary ry y heart hea eart rt ddisease. iseasee. isea Figure 2. Time to Diagnosis of CHD by Number of Years of Hyperlipidemia at Baseline Among Adults Not Recommended for Statin Therapy at Baseline*. This figure shows Kaplan-Meier curves of future risk of CHD stratified by years of hyperlipidemia experienced by age 55 (age range 53–57) among adults not recommended for statin therapy at age 55. Log-rank p-value <0.0001. *Excludes those recommended for statins: ASCVD risk 7.5%, LDL-C 190, diabetes and LDL-C 100. +ASCVD indicates atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CHD, coronary heart disease; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol. 19 DOI: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.114.012477 Figure 3. Prior Weighted Average Cholesterol and CHD Risk. This figure shows the shapes of the restricted cubic spline and piecewise linear models of average non-HDL cholesterol prior to age 55 and the centered linear predictors from the model of time to coronary heart disease. The black curve shows the restricted cubic spline with 95% confidence intervals (dotted) and grey curve shows the piecewise linear spline with knots at 125 mg/dL and 195 mg/dL. The x-axis is truncated at the 5th and 95th percentiles of prior average non-HDL. *CHD indicates coronary heart disease. 20 Incidence of Coronary Heart Disease Years of Follow-Up from Baseline (Age 55) Figure 1 Incidence of Coronary Heart Disease Years of Follow-Up from Baseline (Age 55) Figure 2 Average Non-HDL Prior to Age 55 Figure 3 Centered Linear Predictors from Model of Time to CHD

© Copyright 2026