The Transcendental Logic

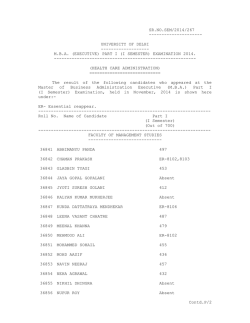

Philosophy 190: Seminar on Kant Spring, 2015 Prof. Peter Hadreas Course website: http://oucampus.sjsu.edu/people/peter.hadreas/courses/Ka nt/index.html The Transcendental Logic: Introduction, Metaphysical Deduction pp. 193 - 218. Critique of Pure Reason Prefaces Introduction First Part Trans. Aesthetic Transcendent al Doctrine of Elements Second Part Trans. Logic Division Two: Trans. Dialectic Division One: Trans. Analytic Book I: Analytic of Concepts Transcendent al Method Book II: Analytic of Principles Introduction Book I: Concepts of Pure Reason Book II: The dialectical inferences of pure reason Transcendental Doctrine of Elements; Second Part: Transcendental Logic. Chapter one: Logic in General First two paragraphs contains a review of key basic Kantian distinction and doctrines: 1. Knowledge springs from two sources: a) the capacity of receiving impressions, b) the power of knowing an object or state of affairs through the spontaneous administration of concepts. “Intuition and concepts constitute therefore, the elements of all our knowledge . . . ” (p. 193) 2. “Both [intuitions and concepts] are either pure or empirical.” (p. 193) 3. “Empirical, if sensation (which presupposes the actual presence of the object), is contained therein; but pure if no sensation is mixed into the representation.” (p. 193) Transcendental Doctrine of Elements; Second Part: Transcendental Logic. Chapter one: Logic in General 5. Key sentence: “Thus pure intuition merely contains only the form under which something is intuited, and pure concept only the form of the thinking of an object in general.” (p. 193) 6. “ Only pure intuitions or concepts alone are possible a priori, empirical ones only a posteriori. (p. 193) 7 “. . . the spontaneity of cognition, is the understanding.” (p. 193) 8. “Without sensibility no object would be given to us, without understanding none would be thought. Thoughts without content are empty, intuitions without concepts are blind. . . Further, these two powers or capacities cannot exchange their functions. The understanding is not capable of intuiting anything, and the senses are not capable of thinking anything.” (pp. 193-4). Transcendental Doctrine of Elements; Second Part: Transcendental Logic. Chapter one: Logic in General 9. A general but pure logic therefore has to do with strictly a priori principles. . . .” (p. 194) Consider as an example the rules of valid syllogisms of derivations in a propositional calculus 10. “A general logic, however, is called applied [and therefore not pure] if it is directed to the rules of use of the understanding under the empirical conditions that psychology teaches us.” An example today would a description of logical fallacies, e. g., arguments ad hominem, ad misercordiam, by pity, or ad periculum, by fear. It is usually called ‘informal logic’ today. Kant’s Discovery: Transcendental Logic 11. “In the expectation, therefore, that there can perhaps be concepts that may be related to objects a priori, not as pure or sensible intuitions but rather merely as acts of pure thinking, that are thus concepts but of neither empirical nor aesthetic origin, we provisionally formulate the idea of a science of pure understanding and of the pure cognition of reason, by means of which we think objects completely a priori. Such a science, which would determine the origin, the domain, and the objective validity of such cognitions, would have to be called transcendental logic, since it has to do merely with the laws of the understanding and reason, but solely insofar as they are related to objects a priori and not, as in the case of general logic, to empirical as well as pure cognitions of reason without distinction.” (p. 196) Kant’s Divides Transcendental Logic into Analytic and Dialectic 12. “In a transcendental logic we isolate the understanding (as we did above with sensibility in the transcendental aesthetic), and elevate from our cognition merely the part of our thought that has its origin solely in the understanding. . . . The part of transcendental logic, therefore, that expounds the elements of the pure cognition of the understanding and the principles without which no object can be thought at all, is the transcendental analytic, and at the same time a logic of truth. Kant’s Divides Transcendental Logic into Analytic and Dialectic 12. “But because it is very enticing and seductive to make use of these pure cognitions of the understanding and principles by themselves, and even beyond all bounds of experience, . . . the understanding falls into the danger of making a material use of the merely formal principles of pure understanding through empty sophistries, and of judging without distinction about objects that are not given to us, which perhaps indeed could not be given to us in any way. . . . The use of the pure understanding would in this case therefore be dialectical. The second part of the transcendental logic must therefore be a critique of this dialectical illusion, and is called transcendental dialectic . . . in order to uncover the false illusion of their groundless pretensions . . . (p. 200) Thinking Requires Intuition + Concepts. Kant Calls that Cognitive Activity ‘Judgment’ “We can, however, trace all actions of the understanding back to judgments, . . . For according to what has been said above it is a faculty for thinking. Thinking is cognition through concepts. Concepts, however, as predicates of possible judgments, are related to some representation of a still undetermined object. The concept of body thus signifies something, e.g., metal, which can be cognized through that concept. It is therefore a concept only because other representations are contained under it by means of which it can be related to objects. It is therefore the predicate for a possible judgment, e.g., "Every metal is a body." The functions of the understanding can therefore all be found together if one can exhaustively exhibit the functions of unity in judgments. The following section will make it evident that this can readily be accomplished.” (p. 205) The Functions of Thinking – and Thinking Consists in Making Judgments -- Can Be Expressed Through Twelve Basic Types of Judgment. In Kant’s Language they will involve three ‘moments’ and four ‘titles.’ This Uncovering of the Basic Types of Judgments Will Provide the Clue to the Discovery of the Pure Concepts of Understanding,” aka “The Transcendental Categories of Understanding” (pp. 206) TABLE OF JUDGMENTS: p. 206 four heads and three moments. Aspect of Judgment(s) Feature of the Judgment(s) Form of Judgment(s) Explanation of Form of Judgment(s) Quantity About the subject of the judgment Universal All S are P Particular Some S are P Singular This S is P Affirmative P belongs to S Negative No P belongs to P Infinite S belong to non-P Categorical S is P Hypothetical If S is P, then R is Q Disjunctive S is either P or Q Problematic judgment is possible Assertoric judgment is actual Apodeictic judgment is necessary Quality Relation Modality about the predicate of the judgment How judgments interrelate within syllogisms Modality of the judgment as a whole capybara largest rodent in the world capybara largest rodent in the world Laughing Kookaburra (Dacelo novaeguineae) perched on a Silver Wattle (Acacia dealbata), Waterworks Reserve, Hobart, Tasmania, Australia Aspect of Feature of the Judgment(s Judgment(s) ) Form of Judgment(s) Examples of Form of Judgment(s) Quantity Universal All capybaras are rodents Particular Some capybaras are males. Singular This capybara is female. Affirmative This kookaburra is a symbol of Australian wildlife. Negative This kookaburra is a not symbol of Australian wildlife. Infinite This kookaburra is non-symbol of Australian wildlife. Categorical A kookaburra is a bird. Hypothetical If a kookaburra calls, then it is defining its territory. Disjunctive Either the the kookaburra’s call is defining its territory or seeking a mate. Problematic Possibly this capybara is tame. Actually this capybara is tame. Necessarily this kookaburra is carnivorous. Quality Relation Modality About the subject of the judgment about the predicate of the judgment How judgments interrelate within syllogisms Modality of the judgment as a whole Assertoric Apodeictic “Robert Hanna on the Primacy of the Faculty of Judgment for Kant”1 “The three leading features of this account are, first, Kant's taking the innate capacity for judgment to be the central cognitive faculty of the human mind, in the sense that judgment, alone among our various cognitive achievements, is the joint product of all of the other cognitive faculties operating coherently and systematically together under a single higherorder unity of rational self-consciousness (the centrality thesis); second, Kant's insistence on the explanatory priority of the propositional content of a judgment over its basic cognitivesemantic constituents (i.e., intuitions and concepts), . . . “ [continues] “Robert Hanna on the Primacy of the Faculty of Judgment for Kant” “. . . and third, Kant's background metaphysical doctrine . . . that judgments are empirically meaningful (objectively valid) and true (objectively real) if and only if transcendental idealism is correct (the transcendental idealism thesis).” 1. Hanna, Robert, "Kant's Theory of Judgment", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2014/entries/kant-judgment/> Connecting Up Kant on ‘Judgment’ in the Critique of Pure Reason to Kantian Philosophy as a Whole. “Judgment is general is the faculty of thinking the particular as subsumed under the universal. If the universal (the rule, the principle, the law) is given, the judgment which subsumes the law under it (even if it prescribes it as transcendental judgment a priori the new conditions under which alone can be subsumed under that universal) is determinative. But if only the particular is given, for which the universal is to be found, the judgment is merely reflective.”1 1. Kant, Immanuel, Critique of Judgment, Introduction, IV (V, 248) (Ak. V, 179). Goethe on Apprehending the Explanatory Power of Kant’s Critiques Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749 –1832) “Here I saw my most diverse thoughts brought together, artistic and natural production handled the powers of aesthetic and teleological judgment mutually illuminating each other . . . I rejoiced that poetic art and comparative natural knowledge are so closely related, since both are subjected to the power of judgment.”1 1. As cited by Cassirer in Cassirer, Ernst, Kant’s Life and Thought, Haden translation, (New Haven/London: Yale University Press, 1981), p. 273. Graham Bird on the Relation of the Table of Judgments to the Table of Categories1 “Kant’s more specific intention to identify categories through, or even with, fundamental judgment forms is open to objections other a dubious reliance of his logic. Recent philosophy has a tradition in which logic and language are conceived as reliable guides to the formal structure of experience, and Kant’s project has something in common with that view. In different ways Russell, Wittgenstein, Carnap and Quine have all been prepared to endorse Kant-like views about a a logical structure for experience but they would disagree with Kant on several issues. Quine would disagree with Kant’s belief that judgment forms provide the most fundamental features of language, since he held, rather obscurely, that ‘the whole of science’ rather than judgment so the unit of ‘empirical significance.’” [continues] Graham Bird on the Relation of the Table of Judgments to the Table of Categories continued from previous slide: “But none of these recent philosophers understood the idea of logic as a formal structure in Kant’s way. The most they would concede is that logic in general, and its preferred systems, provide for the forms in which our experience, especially scientific experience, is expressed.” 1. Bird, Graham, The Revolutionary Kant, (Chicago and La Salle, IL: Open Court, 2006), p. 265 TABLE OF CATEGORIES: p. 212 Notes on Table of Categories Kant mentions pure derivative concepts, he calls them "predicables” e. g. from causality, 'force' 'action' and 'passion.' Under the category of community, 'presence,' 'resistance.’ If not elements in a reduction, Kant clearly sees these predicables as capable of being traced back and developmentally originary from the twelve categories of understanding. (pp. 213-4/B 108) Notes on Table of Categories Kant asserts ”. . . the third category always arises from from the combination of the first two in its class.” (See citation from Hegel on slides #28 and 29 on appropriation of a developmental sense among categories.) (p. 215/B111) Notes on Table of Categories Kant finally considers the so-called ‘syncategorematic terms’ proposed Scholastic philosophers of every being, namely, ”the one, the true, and the perfect: quodlibet ens est unum. verum, bonum. Kant explains that these syncatagorematic terms in terms of coalignments of the Categories. Thus discourse and knowledge is a qualitative unity if it to have a comprehensive significance, as ”. . . the theme in a play, a speech, or fable.” The more consequence from a judgment the more truth. Thus truth is a qualitative plurality. And the greater the totality of a body of knowledge agrees with itself, the more qualitative totality or perfection. (p. 217/B114-5). Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel (1770 –1831) Hegel on the Dynamic Interconnection of Kant’s Categories1 “Kant was the first definitely to signalize the distinction between Reason and Understanding. The object of the former, as he applied the term, was the infinite and unconditioned, of the latter the finite and conditioned. Kant did valuable service when he enforced the finite character of the cognitions of the understanding founded merely upon experience, and stamped their contents with the name of appearance. But his mistake was to stop at the purely negative point of view, and to limit the unconditionality of Reason to an abstract self-sameness without any shade of distinction. It degrades Reason to a finite and conditioned range of understanding.” [continues] 1. from Hegel's Logic: Being Part One of the Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences (1930) translated by William Wallace, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975), p. 73, Note to §45. Hegel on the Dynamic Interconnection of Kant’s Categories1 [continued from previous slide] “The real infinite, far from being a mere transcendence of the finite, always involves the absorption of the finite into its own fuller nature. In the same way Kant restored the Idea to its proper dignity: vindicating it for Reason, as a thing distinct from abstract analytic determinations or from the merely sensible conception which usually appropriate to themselves the name of ideas. But as respects the Idea also, he never got beyond its negative aspect, as what ought to be but is not.” 1. from Hegel's Logic: Being Part One of the Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences (1930) translated by William Wallace, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1975), p. 73, Note to §45. Slides #1, 3, 4, 5, Portrait of Immanuel Kant in mid-life: http://www.lancaster.ac.uk/users/philosophy/courses/100/Kant003.jpg Slide # 2, photograph of a capybara: https://www.google.com/search?q=capybara&bi Slide # 3, photograph of a capybara: https://www.google.com/search?tbm=isch&tbs= slide #21: photograph of Goethe: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Johann_Wolfgang_von_Goethe#mediaviewer/File:Goethe_ %28Stieler_1828%29. slides # 28, 29, 30, portrait of Hegel: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Georg_Wilhelm_Friedrich_Hegel#mediaviewer/File:Hegel _portrait_by_Schlesinger_1831.jpg

© Copyright 2026