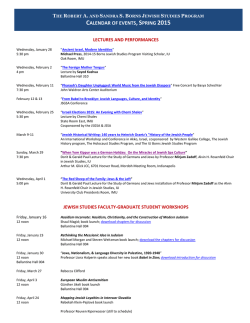

Distinctive Characteristics of Jewish Ibero