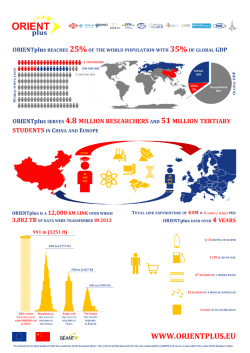

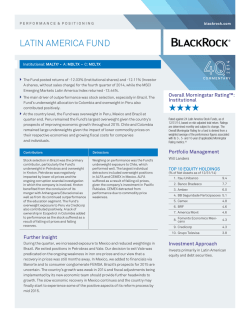

China`s Evolving Role in Latin America