BORDERSENSES

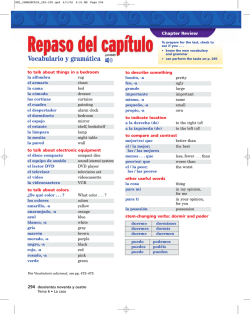

B order S enses L iterary & A rts J ournal V olume 21 F all 2015 BORDERSENSES ©2015 BorderSenses is a literary and arts journal published annually by BorderSenses, a non-profit 501 (c)(3) literary organization. Donations and gifts to BorderSenses are tax-deductible to the extent allowed by law. SUBMISSIONS We welcome submissions of original fiction, nonfiction, poetry, translations, book reviews and visual art. Submissions are accepted in English and/or Spanish. BorderSenses only accepts web-based submissions. Please visit us at bordersenses.com for complete guidelines. EMAIL: [email protected] ADDRESS: P.O. Box 1348, El Paso, TX 79948 BORDERSENSES EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR Yasmin Ramirez PUBLISHER Amit Ghosh MANAGING EDITOR Lacy Arnett SPANISH EDITOR Sylvia Aguilar Zéleny POETRY EDITORS Robin Scofield Maria Miranda Maloney COVER ART Soul of a Mannequin by Ernest Williamson III POETRY CONTEST JUDGE Luis Alberto Urrea DESIGN Paul Haist Editor’s Note Years ago, I visited the Sonora Desert Museum in Tucson. Peering through the glass case of a rattlesnake, I noticed that her face looked a little wonky—maybe some kind of snake-battle scar? Upon closer inspection, I saw that she was beginning to shed her skin. I stood rooted, watching her rub up against items in her case, not unlike a kitten on a pant leg—yawning wide to get the skin off her head and then dragging the rest off through the rocks. I was fascinated and stayed to watch for the 15 minutes it took to slink off the skin from tip to tail. That providential window of transformation for which I happened to be present. It reminded me of a passage I read in Joseph Campbell’s The Hero with a Thousand Faces. He talks about how all of history and myth—the collective unconscious—tutors us in the essentialness of our own death and rebirth cycles: “We have not even to risk the adventure alone; for the heroes of all time have gone before us; the labyrinth is thoroughly known; we have only to follow the thread of the hero-path. And where we had thought to find an abomination, we shall find a god; where we had thought to slay another, we shall slay ourselves; where we had thought to travel outward, we shall come to the center of our own existence; where we had thought to be alone, we shall be with all the world.” If you’re wondering what to do next with your life, now you know: Read Joseph Campbell. After you read this issue, of course. BorderSenses has a long tradition of examining crossover— the lines between two very different spaces. This concept needn’t always be geological. This issue contains essays, stories and poetry in both Spanish and English that explore the passage between health and sickness, youth and aging, faith and disillusionment. The selected art (visual and written) in Volume 21 illuminates the fact that if we are living, if we are awake and paying any kind of attention at all, then we will find ourselves forever transforming, passing between borders, shedding—sometimes beautifully, more often painfully—our former selves. Lacy Arnett Contents Poetry Contest Winners First Place: Our Lady of San Juan del Valle by Natalia Trevino.........23 Second Place: Penance by Leslie Marie Aguilar....................................7 Third Place: Deity by Kate Kingston...................................................59 Fiction English Hearts of Palm by Elizabeth Hoover ....................................................2 The Line of Vision by Lily Iona MacKenzie ........................................9 Seeking Oracles by Donna Snyder .....................................................27 Rumour of a Seventh Head by Marc Labriola ...................................60 Life Like Weeds by Jason Lucero ....................................................106 Spanish Montana por Itzel Guevara .................................................................18 Canto fúnebre por Imanol Caneyada ..................................................30 Café Kamikaze por Iván Farias .........................................................70 Héroes entre nosotros por Alfonso López Corral ...............................93 Corona juarense por Diana Esparza Lara ........................................125 Nonfiction English Pineapple Piñata by James Robinson .................................................42 TESTIMONIO #17 by Philip Garrison .............................................82 Caminar: to Walk by Joshua Moreno .................................................86 Indulgence by Candace Jaffe ............................................................114 The Body is a Promise by Rashaan Alexis Meneses.........................131 Spanish Memorias en chun kuns por Rosa Espinoza .......................................47 Poetry English Seam by Leah Gómez .........................................................................28 Na’nizhoozhi by Dwayne Martine .....................................................29 Pilgrimage by Carla Hagen ...............................................................38 Walking into the Mouth by Carmela Lanza .....................................109 After a Tooth Extraction, Zen by Jonathan Travelstead ....................81 The Ice Harvester by Diana Anhalt ..................................................105 The Tipping Point by Johanna DeMay .............................................104 Reassurance from a Friend After an IVF Failure by Andrea Beltran...........................................................................56 Sonora Desert Fragment by Jeffrey Alfier ..........................................80 The Reason We Don’t Come Over For Your Daughter’s Birthday by Lupe Méndez ..............................................................................6 Blind Woman by Agustín Cadena, translated by C.M. Mayo ............57 The Rental by Jamie Ross ................................................................122 Learning the World by Marian Haddad .............................................66 Border Folk by David Bowles ............................................................91 Penance by Leslie Marie Aguilar .........................................................7 Curvas Peligrosas by Susan Florence .................................................58 Deity by Kate Kingston ..................................................................... 59 Obsolete by Nancy Lechuga .............................................................111 It’s Still Out There by P.W. Covington ..............................................128 Our Lady of San Juan del Valle, San Juan de los Lagos, Depending Which Side of the Border You Believe In by Natalia Trevino .........................................................................23 Blood Games by Suzana Huerta ........................................................16 Lineage by Jed Myers .........................................................................13 Gloria of Palenque by Maria Elena B. Mahler ...................................68 Spanish Minería by Sara Uribe ..........................................................................4 Día de precipitaciones por Guerrero Maricela .............................39, 41 Ceniza constante más allá del amor por Yolanda Segura ...................45 Plan de Acción Internacional para la Conservación y Ordenación de los Tiburones, (PAI-TIBURONES) elaborada del 23 al 27 de abril de 1998, en Tokio, Japón por Xitlalitl Rodríguez ...................................................................84 Hay un lugar que encontré por Radjarani Torres................................11 Art From Cantos of Sorrow by Maceo Montoya Prescience of the Wind .........................................................................1 The Last Eulogies of Poets ...................................................................8 Inspiration of a Mournful Song ..........................................................15 Faith of Those Lost .............................................................................27 Drowned Remains of Winter Storms ..................................................40 Pleas of a Broken Man ........................................................................67 Cruel Violence of Families ...............................................................113 Death Beds of Patriarchs ..................................................................130 Book Reviews Firestarters: a review by Katie Hoerth ............................................141 Nenitas: a review por Sara Uribe .....................................................144 What the Editors Are Reading.......146 Contributors .........................................................147 Prescience 0f The Wind BorderSenses • Vol. 21 1 Hearts of Palm, Canned Elizabeth Hoover …her entire life searching for the elusive sea unicorn or narwhal, the radio ribbons into my sleep: a series about a marine biologist. She is explaining their mating habits when the radio clicks off. By the time I get up and turn it back on they are talking about foreclosure rates, entire cities empty. I look up narwhal on the Internet, a white creature with a wide grin and spiraled tooth. The next morning, the nets bounce, she struggles into her survival suit. What do narwhals sound like? Like seals or dolphins? Or do they glide silently, communicating with smells and signs? The scientist sounds young. She laughs a lot. She laughs about the nets and about not catching anything. She laughs when the reporter asks if she’s read Moby-Dick. The radio clicks off before she answers. When I turn it back on, houses, bereft of their owners, weep vinyl siding and fling shingles to the ground. At work, I think of the arctic and the woman struggling into her suit because she hears the narwhal’s cry. Or is it the iceberg starting to crack? I drag numbers from a spreadsheet into another spreadsheet. After work, I squint at my list in the tundra of the grocery store. Hearts of Palm. I can’t remember writing that or what hearts of palm are. At home I open the can and find salty chunks of white flesh. The scientist wanted to be a dancer. One day she lifted into an arabesque, heard her ankle crunch like a walnut and knew. What did you know? The radio clicks off, and the houses sprout kudzu and cutflower. I click to a spreadsheet so my boss won’t catch me reading about narwhal songs. She uses a spear to stab a transmitter into a narwhal’s flank, trying to find out where they go in winter. Do they dive into the deep to hibernate or follow warmer currents south? I know where I go in winter: I go to work. I go to the grocery store. I go home with my canned goods. I dive shallower and shallower no matter the season. I arrange the hearts of palm on a plate and she eats them with her hands, sucks brine off her fingers. She laughs about Moby-Dick and the crush of her tiny bones. Why don’t you just ask them? But the chair doesn’t reply. I go to bed early to pass the time before the next broadcast. The 2 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 transmitter slips from the wound. It relays the current, which sounds like a lung. I listen to pebbles grinding, her laughing and sharpening her spear. I enter narwhal gestation periods into a spreadsheet. On Saturday, the radio is hysterical. I listen to markets shatter like china, but the scientist doesn’t come on. On Sunday, the radio weeps for an assassinated world leader and rides the bus to see how commuters are dealing with the recession. On Monday it’s Korean little league and executive suicides. On Thursday, I am out of sick days and the radio hobbles through the wreckage of an exploded marketplace. I fill my trunk with canned hearts, head north. BorderSenses • Vol. 21 3 Minería Sara Uribe Ella viene de Tamaulipas. Y todos sabemos lo que significa venir de Tamaulipas. No lo dijo. Él pensaba en las carreteras. Él decía Tamaulipas pero en realidad quería decir nada. Él dijo Tamaulipas por decir nada. Como quien nombra un territorio perdido. Una región que no existe. Y todos sabemos lo que significa venir de un lugar que no existe. No lo dijo. Él pensaba en el viaje de Tamaulipas a la Ciudad de México. Ellos abrieron ojos y bocas cuando les dijimos que habíamos viajado por carretera. Luego Marco lo dijo: la mejor forma de viajar a Tamaulipas es por carretera. Y ellos abrieron más sus ojos y sus bocas. De tanta boca abierta no pude evitar que las moscas revolotearan. Moscas de la nada surgiendo de un bote de composta del sombrero de un prestidigitador de insectos. Ellos no abrieron los ojos porque nada había para ser visto. Ellos no abrieron las bocas porque nada había para decirse. Y todos sabemos lo que significa venir de un lugar donde nada hay para ser visto, donde nada hay para ser dicho. Una carretera no es un lugar. Una carretera es siempre un limbo. Esta carretera lleva de Tamaulipas hacia ninguna parte. Y todos sabemos lo que significa venir de ninguna parte. Ellos aplaudieron pero estoy segura que la mitad no tiene idea de dónde queda Tamaulipas. Una mujer confundió los cuerpos de las fosas con un desastre de mineros. Todos los cuerpos y todas las carreteras, se sabe, conducen a ninguna parte. 4 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 Ellos no aplaudieron porque en realidad nunca estuve ahí. Nadie leyó un texto sobre un hombre desaparecido. Nadie leyó un texto sobre una mujer buscando un cadáver. Nadie mencionó la palabra fantasma. De haberlo hecho, Marco me habría acusado de decimonónica. No. Nadie habló de fantasmas. Todos aplaudieron aunque no sabían de qué lugar, de qué personas, de qué clase de desapariciones se trataba. Yo nunca estuve ahí. Nadie mencionó la palabra “yo”. De haberlo hecho, Marco me habría acusado de lírica. Este “yo” es, desde luego, retórico. Ficticio. Y todos sabemos lo que significa ser ficticios. Ella dice que Allá hay quien no cree que lo que está pasando Aquí sea Real. Ella dice que creen que Acá todos somos fantasmas. Disculpen, señores, esto es una revisión de rutina ¿hacia dónde se dirigen? Ella viene de Tamaulipas. Y todos sabemos lo que significa venir de Tamaulipas. BorderSenses • Vol. 21 5 Penance The Reason We Don’t Come Over for Your Daughter’s Birthday Leslie Marie Aguilar Lupe Méndez is a bittersweet tangerine sized pill I have to swallow every year. I hope all the beers, the meals I buy you, friend, keep you from being angry at me. I cannot eat birthday cake. A crescent moon sliced at my wife’s womb the night I held my god daughter, and every year when that toddler blows out a candle, we shudder just a tad, a ruffle in our diaphragms – another year she celebrates without a play pal, that looks like us. The blackbirds in the withering pecan tree behind my childhood home never made it into the trash can after my father shot them with his BB gun. They clung to the telephone wires hoping for a last minute resurrection. I found a dead squirrel in that trash can once & wondered how it arrived there because birds weren’t different than squirrels, at that age. Blood from the body is blood from any body & birds aren’t different than squirrels, father, but I’m waiting for the right moment to tell you. Now, I imagine the blackbird as a gun that hides in your closet the night I come home too late. It rattles its wings against the cage of your hands & breaks them over my body. My blood is yours, father, & I’m waiting for the moment to tell you, the five blackbirds tattooed along my ribs use their beaks as knives to carve out a place for you. 6 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 7 The Line of Vision Lily Iona MacKenzie At ninety-two, her expectations are small—pequeño. She just wants to get warm again. This last winter in Calgary was the worst in ages. For weeks on end, the thermometer registered way below zero, though she didn’t let the snow and cold stop her from going out to play bingo or shop at The Bay. She wrapped herself in layers of clothes, her fake fur coat on top. But she still felt the cold more than she ever had. The Last Eulogies 0f Poets On this her first trip to Mexico, to Puerto Vallarta, the tropical weather, temperatures in the high eighties, has dried out her bones, making her light as air, like one of the paper maché masks she saw at a shop on Insurgente. She must return and buy one. Those masks interest her, the animal ones especially. They’re not like any animal she’s seen. That’s why she would like to take one back to Canada—something wild she could hang on her wall, a jackal or a hyena. From the penthouse condo she and her daughter are renting on the beach, south of the Cuale, she watches the town unfold around her. At times she pretends she’s the center of Puerto Vallarta, that everything emanates from her, that she’s the mother of it all. A queen bee watching her workers. And work they do, from morning until past dark, sweeping streets, raking the beach, making tortillas, cleaning rooms, selling all sorts of trinkets and crafts. All of the activity makes her dizzy. So does the ocean—its continuous thrashing, its endlessness, its changeability. During the day, she can see as far as the horizon, the line occasionally broken by a boat. The line’s steadiness comforts her. She can count on it always being there. At her advanced age, anything that seems permanent is reassuring. Everywhere she looks there’s sea and surf constantly in motion. The condo itself seems to be moving. At times in the street, holding onto her daughter's arm, she watches herself tottering along as if from a great distance, feeling unconnected to her human form. She has noticed 8 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 9 this separation happening more lately, and at times she feels confused, uncertain of where she is, floating apart from her body. Suspended. She has always had a vivid imagination. Her father and uncles told her that; it was no news to her. But this isn't just her imagination playing tricks. Something is taking shape— perhaps another body. It just doesn't have a place yet. Being in Mexico makes her more aware of it. Maybe it’s because she doesn’t have to use so much clothing here. She truly is lighter. When she watches the surf surging forward, the sound at times like thunder, it all becomes clear to her for a moment, but then she loses it again. She’s like a wave losing itself on the shore, turning to froth that dissolves, gripping and dragging sand and whatever gets in its way back out to sea. She’s both wave and what dissolves. She wants to tell her daughter this, but it’s hard to put into words. She isn't sure she really understands. She likes to think she will live forever, but she's no fool. Her friends are dying around her like flies. No one outlives death. Does that mean death doesn't outlive death? That at some point death will die too? The thought encourages her. Mexico makes her think of mortality. Her mother died in Mexico City in 1930 not long after her 50th birthday. Alone, or, at least, without her family. She’d left her abusive Scottish schoolmaster husband, traveling south with another man, her lover. A middle-aged woman trying to outrace death. It caught her anyway. drift into her room off the tiled balcony. But when she tried to grab her arm, it wasn't there. Yet the image remained, and the certainty that she was nearby, watching, waiting—part of the Sierra Madres, the mothers, that embraced this bay. The parasailors drift past the balcony, heading for the beach. She's been watching them every day being pulled by a boat over the Pacific and back again. If she were younger, she would try it herself, and she urges her daughter to go up. She wants to see her rise over the water and return to earth again, alive. It feels like a rehearsal for death, to float above the land not exactly in your own flesh, the sail filled with air holding you aloft. How different was that sail from this body? Her daughter refuses. “I'm too old, Mum. Besides, what if something happened to me? How would you get back to Calgary?” It’s a good point. Her body doesn't function as it used to. She has trouble walking on the cobblestone streets and uneven sidewalks, never knowing when it’s all going to dip or disappear altogether. She doesn't persist. On the last day in Puerto Vallarta, she asks her daughter to take her to the beach. “I want to dip in the sea again. I used to swim in it when I was a girl, you know, off Skye. The Atlantic.” On her second night in Puerta Vallarta, an orange-colored crescent moon had hung suspended in the sky, as if from a string, like a trinket off one of the mobiles she saw vendors selling on the beach. It didn’t seem real, or it was too real to believe. They trudge across the scorching sand. A vendor shuffles past, ten sombreros stacked on his head. “A hat, Señora?” Behind him strolls an Indian woman, reams of silky flowered material draped over her body. “A skirt, Señora? Look, it wraps around like this. Fits any size.” And she demonstrates, tying a strip of fabric around her hips. Fish carved out of wood, mobiles trailing vividly colored fish and butterflies, jewelry, blankets, charbroiled fish on a stick—all these things swirl around her at once. And the masks, just like the ones she saw in the shop. Bobbing up and down. Alive. Sometime during the night, she was sure she saw her mother She can hardly bear the heat, the soles of her feet burning 10 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 11 with each step. She should have worn her shoes. Then the sand turns cool, damp from where the waves recently washed it and a darker shade of beige. Her footprints look strange, her feet bigger than she thought, but the indentations so temporary. Another wave rushes towards them, froth bubbling over their feet, and washes away the imprints. “Do you want to go farther, Mum?” “A little. I'd like to get a good soak.” Back slightly bent and skin sagging in folds, she clings to her daughter's arm as they walk slowly, stopping when another wave rolls towards them, slapping their bodies and almost knocking them over. She screams, “My shoes, they're gone!” The sun blinds her, mixed up with the ocean, salt water in her mouth. Everything seems to be spinning—the vendors, the sun, the beach-front restaurants. Her daughter stands there, steady. Lineage Jed Myer How much could memory weigh? I thought, still on the easy part up the rocks to the ancient puebloans’ granary. Up—out of the grove of the centuriesold black-branched mesquite, roots deep through the dust and into the schist— I walked, awkward out of my city, a tiny-leafed thorned acacia catching my sleeve “It's okay, Mum, you weren't wearing shoes.” as if to ask Wait a minute, where do you get the right to climb here like this? So I did hesitate, a catch in my breath, The wave drags sand from under her feet, leaving two small graves, and she hears a whooshing sound, the surf snatching at her again. as by my bones I did bear a weight, a history’s heft. I’d have to breathe for my grandfather panting in Philadelphia Her daughter grabs her arm and holds on. The old woman stares out to sea, as if looking into a crystal ball, her future somehow held there. Flooded by memories of her youth on the Isle of Skye, she bursts into song: heat, grandmother gasping at gallbladder pain cramping her diaphragm, sweet Mrs. Gregory rasping out the Old Testament Speed bonny boat like a bird on a wing, Onward the sailors cry. Carry the lad that's born to be King, Over the sea to Skye. Her daughter laughs, and they stand there, arm in arm. The old woman stares at the ocean’s edge, stark against the horizon. Its line steadies her. story of Jacob planting his head on a rock in the sand, my mother sputtering smoke as she crushed the night’s last cigarette, Dad croaking awake in a spiderweb tangle of tubes on his hospital bed…. Thus I huffed the twists through the talus up the red cliff—they’d hid the grain in a few squat silos of cut stone. They must’ve carried their own unforgotten, living and dead, in their chests, along with the baskets of sustenance strapped to their backs. I imagined them 12 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 13 black-haired and thin, deft in their steps where the gritty path steepened, toes flexed on the slippery footholds, and intent as I found myself, hauling the souls who’d shared breath with us up the slope to those dark-holed eyes in the earth. Inspiration of a Mournful Song 14 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 15 Blood Games Montana Suzana Huerta Itzel Guevara Summer nights in Tlachichila are wrapped in stars, blanketed in light points infinite and pulsing. It’s July—me and my primos walk this cobbled mountain road, chasing fire with no regard for holes or pits, gaping and ready to twist our feet, my ankles so weakened by Northern California asphalt and concrete. Ese día, después de mucho pensarlo, decidiste aceptar la invitación de Muchachito y Vladi a jugar una partida de póker, ni siquiera sabías jugar. Eso es lo de menos, había dicho Muchachito, ninguno sabe, yo les enseño, además lo importante es reunirnos. I don’t know the bulbs that bounce before me are creatures. I am certain they are tiny stars extended on the fingertips of heaven—God reaches to earth more easily down here—my mom told me once—said Mexico was filled with miracles, like when she survived spinal meningitis with only prayers and poison coursing through her veins. Te prometiste nunca hacer una cosa así, nunca perseguir a un hombre, nunca acosarlo y de hecho lo estabas cumpliendo, entre él y tú ya no había nada. Sí, es cierto que recién habías puesto punto final a esa relación, si es que así se le puede llamar a lo que tuvieron, punto final que él había interpretado como punto y seguido porque continuaba buscándote, llamándote para decirte cuánto pensaba en ti, mirándote durante las dos horas de la clase que tomaban juntos. Nunca antes dos horas te parecieron tantos minutos. Dejándote poemas entre los libros, pidiéndote que hablaran, asegurándote que las cosas se podían salvar. Tú sólo lo escuchabas, no respondías, ya no respondías porque estabas convencida de que no había marcha atrás. Y ahora estabas en casa de Muchachito y Vladi, que también era su casa, y la de ella, y la de Jonas y Mel, dos ingleses que estaban de intercambio este semestre. So I grab at these tiny constellations, break them apart with eager hands, managing only screams because already my Spanish is fading and my broken breath cannot keep up with my mind. I run aimlessly- bumping into my cousins’ elbows and shoulders as we reach for the same, impossible, burning lights. We pull the dancing lights into our hearts—smear them across our chests and forearms, blend their fluorescence into our sweaty palms and cheekbones. Julio, the neighborhood boy who runs with girls and shares his mother’s make-up, holds my face in his hands as he rubs a light across my forehead, blessing me, como el padrecito, he whispers and kisses it with love. Together our fingertips and necks are aglow with fast fading fires in the night. Returning to my tia’s kitchen, warm and yellow and thick with the scent of beef stew and canela cider, I am shocked to find the guts and legs of these light creatures blurred across my skin, soiled so deeply into my new summer dress, their faded blood no longer glowing. It is then I notice my own blood, a bright, crimson stream so fine it looks like a ribbon unfurling from the hem of my dress, grazing the inside of my thighs. I don’t know what to make of it. All I know in that instant is that the broken bodies I had killed and rubbed out, so dangerously close to my open lips, gave me a hunger so deep, I could hardly stand the wait for supper and song. 16 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 A pesar de la situación te sentías bien, siempre te ha gustado la sensación de ser la única mujer en un grupo de hombres. Te atrae su comportamiento en manada y sobre todo esa especie de hermandad, de cofradía prácticamente inquebrantable que forman cuando están juntos, cuando sólo se tienen los unos a los otros. Nunca has entendido del todo los códigos de lealtad masculina, las reglas implícitas que rigen al grupo, por eso te gusta estar con ellos, los observas, los escuchas, a veces les pides que te expliquen por qué hacen tal o cual cosa y ellos, con mucha seriedad, intentan responderte. Siempre te conmueves por la muestra de respeto ante tu curiosidad. Fuiste porque no había razón para esconderse. No voy a buscarlo, voy a ver a mis amigos, fue la frase que te decidió, BorderSenses • Vol. 21 17 y en verdad estabas convencida, estabas segura de que a pesar de esos pequeños momentos de debilidad, como tú los llamabas, lo habías superado. Tu problema es que siempre necesitas comprobar las cosas. Llegaste y todos celebraron tu presencia, en especial Muchachito, quien de inmediato acercó una silla y te quitó de las manos la bolsa de frituras que llevabas para acompañar las cervezas. Luego te preguntó qué querías escuchar y tú le pediste una de Sabina. Estabas un poco tensa, no podías dejar de pensar que era su casa, que en cualquier momento podía entrar a este espacio que no es cocina ni sala ni comedor, sino un híbrido al que aún le estás buscando nombre, que también ella podía entrar y entonces ¿qué ibas a hacer? Sin embargo, las risas idiotas que los chicos soltaban cada vez que Muchachito los regañaba por realizar una jugada sin sentido que intentaban hacer válida y los vasos de cerveza ingeridos ininterrumpidamente te fueron relajando hasta el punto de que estar en el 909 de la Avenida Montana dejó de preocuparte. Vladi y Jonas se enfrascaron en una discusión sobre si Sabina era un poeta marginado o un estúpido resentido sin talento que en lugar de cantar ladraba. Aprovechaste la distracción para escabullirte a fumar un Marlboro, te estabas aguantando las ganas desde hacía rato y consideraste mejor dejarlos solos para que se destrozaran, segura estabas que no llegarían a ninguna conclusión. Cruzaste el pasillo tambaleándote un poco (después de todo te la habías pasado bebiendo), hasta alcanzar el patio. Era un patio grande y ya le habías oído decir a los chicos que sería perfecto para las fiestas porque cabía mucha gente, pero aunque había algunas plantas sembradas a lo largo de la reja metálica que marcaba lo límites de la casa con la calle, te pareció que ahí reinaba un aire de irremediable descuido, como en toda esta ciudad, pensaste. Mientras encendías el cigarro, viste pasar un gato. Los gatos estaban por todos lados, gatos amarillos, blancos, marrones, manchados, atigrados. Le habías dicho que esa fue una de las cosas que te sorprendieron al llegar, por eso cuando salían contaban los gatos que se encontraban en el 18 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 camino. También le hablaste de los aviones, de la maldita manía que habías adquirido de voltear al cielo cada vez que escuchabas el ruido del motor. Los aviones se habían convertido en la posibilidad, tu única posibilidad de volver a casa. Y como las ideas se fueron asociando a emociones sin que te dieras cuenta, los aviones eran nostalgia, eran no saber por un momento dónde estás, eran sentirse pequeña. Un día, bajo el rugido del avión, te tomó la mano y dijo, estás aquí, estás conmigo. Cuando el gato se percató de tu presencia, pegó un salto y de puntitas, como si fuera una bailarina, se alejó caminando sobre la reja. Entonces notaste que el cigarro se había apagado, que llevabas un buen rato sentada al fondo del patio. Pensaste que si alguien hubiera salido a buscarte, habría creído que te habías marchado, porque incluso pasando a tu lado, era imposible reconocerte en medio de esa oscuridad, pensaste que era un buen escondite. Tiraste el cigarrillo y regresaste a la casa, al pasar junto al baño la escuchaste reír. Te quedaste ahí, frente a la puerta blanca, te quedaste escuchando su risa que era auténtica, y también inocente, casi infantil, sabías que era muy joven pero no imaginaste cuánto. Era como la risa de una niña emocionada porque le acaban de compran un globo, porque está en el circo y ve a los elefantes marchando, porque va a hacer su primera comunión y la vistieron toda de blanco. A él no lo oías, no era necesario, sabías que estaba con ella, que se estaban bañando, oías el agua cayendo, el chapoteo de sus pies, sabías que él la enjabonaba como si fuera una muñeca, que ella se alegraba de ser su muñeca. Todos cometemos errores, me dieron la beca y tenía que venirme ya, habíamos convivido poco, y… casarme fue una decisión apresurada. Eso fue lo que te dijo el día que lo confrontaste, el día que te esperó fuera de clase para acompañarte a casa y finalmente te propuso que tuvieran algo, que empezaran algo. Te lo dijo mirando al suelo, a los escalones donde estaban sentados. ¿Iniciar algo?, ¿iniciar qué?, cómo inicias algo cuando tienes una mujercita esperándote en casa, cuando ni siquiera es una casa, tan sólo un cuarto rentado donde compartes todo, hasta el baño. BorderSenses • Vol. 21 19 Sus palabras te resultaron poco convincentes, casi una burla, pero cuando te jaló hacia él, cuando hizo un espacio en su cuello para que colocaras tu cabeza y comenzó a acariciar tu brazo apenas deslizando las puntas de sus dedos, entonces todo tuvo sentido. ¿Qué vamos a hacer con esto?, preguntó. No respondiste, simplemente lo besaste. Decidiste no pensar, porque pensar lo complica todo, decidiste concentrarte en esas manos que se metieron bajo tu blusa, que te rozaron el abdomen, que subieron con prisa hasta tus pechos y se estacionaron en ellos y te apretaron como temerosas de que pudieras escaparte. Déjame entrar, te dijo. Tú obedeciste. Muchachito se dio cuenta que no habías regresado y fue a buscarte, pensó que estabas en el porche, generalmente era ahí donde salían a fumar. En cuanto salió de la cocina te vio al fondo del pasillo, parada frente al baño; se acercó, te tomó del brazo, dijo: ven, y te llevo a su recámara. Estuvieron un rato en silencio, oyendo las voces de los chicos que ya se habían enfrascado en una nueva discusión, ahora sobre si el decano de la universidad segregaba a la comunidad latina. Muchachito te puso la mano a un costado del hombro y dijo que estaba ahí para escucharte, tú, como si hubieras estado esperando una señal, empezaste a hablar. Lo hiciste sin escoger las palabras, sin seleccionar la información, como una autómata. No puedes recordar, incluso ahora, qué fue lo que dijiste, si entraste en detalles o si hablaste sólo en términos generales, como sueles abordar las cosas, tampoco puedes recordar en qué momento comenzaste a llorar. Muchachito estuvo sentado frente a ti todo el tiempo, de vez en cuando movía la cabeza de un lado a otro con los labios contraídos. Temías escuchar un ¿por qué lo hiciste?, un tú sabías en lo que te estabas metiendo, un ¿pensaste que la iba a dejar por ti?, pero no dijo nada. Te escuchó sin decir nada. Tú lo abrazaste, de eso sí estás segura, necesitabas un recipiente porque estabas a punto de cambiar de estado sólido a líquido. Esas fueron las palabras que utilizaste después para explicarlo. Lo abrazaste y sentiste cómo acariciaba tu cabello, luego se movió para estar más cerca de ti. Te apretó con fuerza y escuchaste su corazón latir rápido, sentiste que tu pena también era suya. Tomó tu cara, 20 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 que estaba recargada en su pecho y se aproximó, escuchaste su respiración, sabías lo que iba a suceder y no pudiste o no quisiste hacer nada para evitarlo. Se besaron, y como necesariamente sucede, el beso es siempre el principio. Dijiste que no querías, y continuaste besándolo, dijiste que no estaba bien, y te tiraste en la cama, le quitaste la camisa, dejaste que él te desnudara. Querías levantarte y salir de ahí pero tu cuerpo se abrazó al suyo, y lo dejaste entrar. Era verdad que estabas excitada, que despertar el deseo de un hombre, de Muchachito, te hizo sentir poderosa, y el poder es fuerza, es dominio, es vencer a una persona, ser más fuerte que ella, cuán necesitada estabas de poder. Pero también estaba esa otra cosa que trataste de apartar, esa especie de eco lejano y a la vez presente que amenazaba con derrumbarte. Comenzaste a sentir miedo y cuando intentaste decirle que era mejor que parara, lo que te salió de la boca fue un gemido, un bello y profundo gemido. Desnuda y abrazada a Muchachito sentiste tristeza, mucha más que en un principio, el problema era que ahora no había nada ni nadie para contenerte. Saltaste de la cama, buscaste con desesperación tu ropa regada por toda la pieza, tu ropa que era ya lo único que tenías, pensaste que si te vestías ibas a recuperar la tranquilidad. Muchachito se despertó y trató de detenerte, pero ya estabas cerca de la puerta, y cuando la abriste te sorprendió el silencio en la casa, parecía deshabitada. Apenas cruzaste el umbral lo viste junto a la puerta de su habitación, la que comparte con ella, como comparten la comida, la hora del baño, la vida. Estaba sentado en el pasillo, con las rodillas pegadas al pecho, lo suficientemente cerca para distinguir en sus manos grandes, manos que tenían el doble de tamaño que las tuyas, los nudillos enrojecidos. Incluso pudiste ver sus venas un poco salidas y los delgadísimos vellos que crecían en sus brazos, sin embargo, estaba lo suficientemente lejos para tocarlo. Sabías que te estaba esperando, que te había escuchado y quería comprobar que eras tú. Te miró, no dijo nada, te miró y en su mirada había dolor, quizás tanto como en la tuya. Muchachito salió poniéndose los calzones y al verlos intentó decir algo. No te quedaste a escuchar. BorderSenses • Vol. 21 21 Saliste a la noche que era amplia, inabarcable, una noche sin nubes ni luna, tan sólo poblada de cientos de estrellas, y te golpeó como una bofetada porque un día, en la celebración que siguió a la presentación de un libro, él dibujó una flor sobre una servilleta de papel y te la dio a escondidas. Qué poco original, hasta pareces hombre, le dijiste; a continuación le arrebataste el bolígrafo y te pusiste a trazar en otra servilleta un montón de asteriscos. Antes de dársela, escribiste: te regalo una noche llena de estrellas. Comenzaste a caminar y tus pasos sonaron sobre el pavimento, los únicos sobre Montana y tuviste la impresión que también eran los únicos en la ciudad. El rugido de un avión cruzó cortando el silencio de la noche, cerraste los ojos para no escucharlo. Our Lady 0f San Juan del Valle, San Juan de Los Lagos, Depending Which Side of the Border You Believe In Natalia Trevino I. I first saw you in my grandmother’s prayers. Daily, she sat up in bed, whispering to your blue-gold image between her thumb and forefinger. Her brown eyes closed. Her prayer easy as the wind coming through the screen. O Maria immaculada. I only knew you were a Mary. Y siempre bendita. And always blessed. Your gown not woven like Guadalupe’s soft drapes, but two stone-stiff triangles, each a winged sky floating above gold leaves, covering you from neck to the floorless moon below your feet. Spread over your thin body into a shape that would travel well as a statue— across the country, across the Rio Grande. Small traveler from Michoacan to the center of Mexico, no one is sure when, barely the size of a dusty book or an old man’s shoe. Somehow holy, somehow miraculous. Dressed in a voice that is blue and stars, you are the original migrant miracle worker. II. Miracles of Misericordia At thirty, I finally listened to my grandmother’s words, Madre de Misericordia, she said, and I only heard what my English could 22 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 23 break apart, Mother of Miser-something, (Misery)? Her back molded into her pillow under that open window, her routine: to pray after she bathed. Washed, her thin strands of hair curled into upside down question marks along her neck. Her well-shaped nails held your prayer card as they would a thin needle. So I asked her, why this Virgen when it was Guadalupe who Mexico loved to burn with holy candles, who brought Juan Diego roses in dead winter. Porque es muy milagrosa, she said, with or without thinking of miracles she’d once wanted in her own house: to end her son’s leukemia, to dry out the pneumonia in my grandfather’s lungs, for her own legs to stand again, to hold a broom, sweep the dust from her street. III. Migrant Virgen, Our Lady of San Juan, your eyes do not look down at Juan Diego from a sky, nor halfshut in grief or compassion—but are armed against the distance above a grail and the moon. Your crown three times as large as your face. Your crown, a floating indigo earth, a planet of water with no land to fight for. Your crown, the earth where we’ve struggled, where we’ve crossed one another and borders with our own travel-sized miracles: miracle of a bottle of water; 24 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 miracle of a photograph tucked under a bra; miracle of a sandwich shared, made three hundred times, three hundred miles away. Your crown, I’ve crossed its brown, Rio Grande, three hundred times and more, where my Green Card, then my blue card, while other children crossed pale deserts, swam and died in that sphere above your head. Madre de Misericordia, Mother of Misery, of Mercy. I am still learning that difference between you and my grandmother, your identical names, Socorro, Mercy. Between Mercy and Mercy, between the prayer and the one who prays. IV. From One Eye to Another My Grandmother held your image no larger than a painted thumbnail, Whispering esos tus ojos reflujentes a mi. She, or was it both of you, crocheted in the light of most afternoons masses of geometrics opening and closing to form fine fabrics— warm embellishments that spread like winged constellations to drape over our own beds, tables, the television, all the largest of human possessions: Maria de Socorro, ‘Buelita whispering colors into the eyes of her needles, esos tus ojos reflujentes a mi.. Those, your eyes, reflecting me on both sides of the border BorderSenses • Vol. 21 25 Seeking Oracles Donna Snyder She gazes at the flame between her eyes, holds her breath until she is nothing but heart, the world’s pulse between her ears. She finds black feathers at her doorstep, unsure if the augury is good or ill. Each night she folds her legs and disappears into the sacred fire. She greets the sunrise with a sigh. Voices echo conversations on eschatology and doom. She hides from them behind guitars’ excruciating sweet. Words repeat themselves perpetually in silence. She sees pictures on the wall where there are none. She knows little of souls but talks to the dead, visits them in their tombs inside her body. Somewhere outside her head, the smell of palo santo smolders. Somewhere, the sounds of hard wind through metal and water dripping. Floorboards creak and a door closes, of their own accord. She never knows whether her ghosts linger, or if she binds them to her, refusing to let them go. In her sleep, she wraps herself in sheets like Lazarus. When she wakes, she arises from the grave into a world of dust and blinding sun, the desert heat a shroud. There are no dreams here, just her third eye ablaze. She dresses in the memory of rain. Her hair a burning nimbus, her reflection falls into the caves beneath her eyes. Everything is bleached as coyote bones in this landscape she wanders, and every living thing has thorns. The path is full of rock, forlorn scat, and sorrow. Everyday she trips and falls. When the flame fades she returns to now, along with ordinary sight. The flicker of candles glows on the other side of her eyelids. The sound of heartbeat subsides and that of barking dogs and sirens resume. She realizes the music had been inside her head, as had the desert, the thorns, and the talking dead. 26 BorderSenses • Vol. 21 Faith of Those Lost BorderSenses • Vol. 21 27

© Copyright 2026