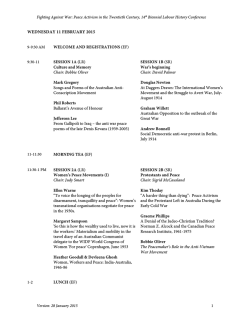

General report, Seventeenth International Conference of Labour