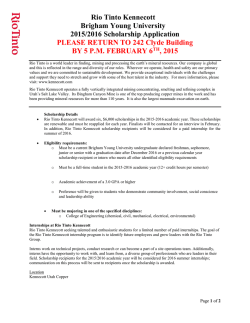

English PDF - Open Knowledge Repository