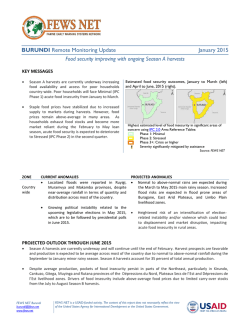

2015: Burundi at a Turning Point