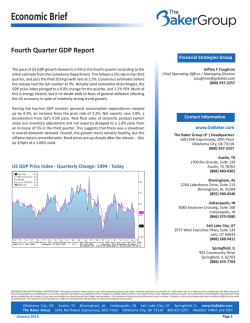

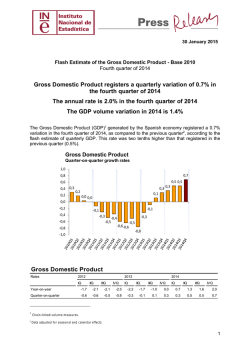

Download (1MB) - Munich Personal RePEc Archive