On Some Problems in the Semiotics of Visual Art: Field and Vehicle

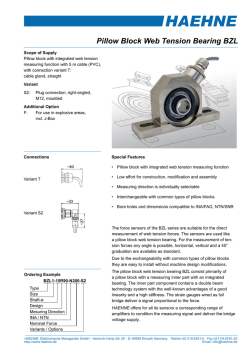

9 On someproblemsin thesemiotics ofvisualart: fieldand vehiclein image-signs* MeyerSchapiro My themeis thenon-mimetic elementsof theimage- creationof potteryand an architecture withregular signandtheirroleinconstituting thesign.It isnotclear coursesofjointedmasonry. It mighthavecomeabout towhatextenttheseelements arearbitrary andtowhat throughtheuse of theseartifacts as sign-bearing obextenttheyinhereintheorganicconditions ofimaging jects.The inventive imagination theirvalue recognized and perception.Certainof them,like the frame,are as grounds, andintimegavetopictures andwriting on historicallydeveloped,highlyvariable forms; yet smoothedand symmetrical supportsa corresponding thoughobviouslyconventional, theydo nothaveto be regularity of direction, spacingand grouping, in harlearnedfortheimageto be understood; theymayeven monywiththe formof theobjectliketheassociated value. ornament oftheneighboring acquirea semantic parts.Throughtheclosure We takeforgranted meansthe and smoothness todayas indispensable ofthepreparedpicturesurface, often rectangular formof thesheetof paperand its clearly witha distinctcolorof thereservedbackground, the defined spaceofitsown,incontrast smoothsurfaceon whichonedrawsandwrites. imageacquireda definite to But sucha fieldcorresponds to nothingin natureor theprehistoric wallpaintings and reliefs;thesehad to mentalimagery wherethephantoms ofvisualmemory competewiththenoise-like accidents andirregularities comeup in a vagueunboundedvoid.The studentof ofa groundwhichwasno lessarticulated thanthesign prehistoric artknowsthattheregularfieldis an ad- and could intrudeupon it. The new smoothness and ofart. closuremade possiblethe latertransparency vancedartifact a longdevelopment presupposing of the The cavepaintings oftheOld StoneAgeareon an un- picture-plane whichtherepresentation without ofthreepreparedground,theroughwallofa cave; theirregu- dimensional spacewouldnothavebeensuccessful.1 laritiesofearthandrockshowthrough theimage.The Withthisnewconception of theground,theartof artistworkedthenona fieldwithnosetboundaries and representation I have said, a fieldwitha constructs, thought so littleofthesurfaceas a distinct groundthat distinct plane(orregularcurvature) ofthesurfaceand he oftenpaintedhis animalfigureovera previously a definite thatmaybe thesmoothed boundary edgesof paintedimagewithouterasingthelatter,as ifit were an artifact. The horizontals ofthisboundary areat first invisibleto the viewer.Or if he thoughtof his own supporting groundlineswhichconnectthefigures with as occupying onthewalla placereserved each otherand also dividethe surfaceinto parallel work,perhaps, forsuccessivepaintingsbecause of a specialriteor bands,establishing morefirmly theaxesofthefieldas custom,as one makesfiresyearafteryearon thesame coordinates ofstability andmovement intheimage. hearthoverpastembers,he didnotregardthisplaceas We do notknowjustwhenthisorganization ofthe a fieldin thesamesensein whichlaterartistssawtheir imagefieldwas introduced; studentshavegivenlittle figuresas standingout froma suitablycontrasting attention to thisfundamental changein art whichis ground. basicforourownimagery, evenforthephotograph, the The smoothpreparedfieldis an invention ofa later filmandthetelevision screen.In scrutinizing thedrawIt accompanies stageofhumanity. thedevelopment of ingsof childrenforthe mostprimitive processesof polishedtoolsintheNeolithicandBronzeAgesandthe image-making, one forgets thatthesedrawings, made * This paperwasoriginally presented at theSecondInternational I Certainoftheseobservations, inmycoursesat Columpresented ColloquiumonSemiotics, Kazimierz, Poland,September I966. [First bia University thirty yearsago,willbe foundinthedoctor'sthesisof publishedin SemioticaI (I969), pp. 223-42, andreprinted herewith mypupil,MiriamS. Bunim,"Space in mediaevalpainting and the thekindpermission oftheauthorandpublisher, Mouton& Co, The forerunners New York(ColumbiaUniversity) ofperspective," I940. Hague.] IO MEYER SCHAPIRO on rectangular sheetsofsmoothedpaper,oftenwitha andgrounddid notcomposefortheeyean inseparable in lookingat an admiredwork variety of colors,inherittheresultsofa longculture, unity.A connoisseur justas theirsimplespeech,afterthephaseoflallation, couldregardtheemptygroundandmargins as nottruly showselementsofan alreadydevelopedphoneticsys- partsofthepainting, as thereaderofa bookmightsee temand syntax.Theirformsare soonadaptedto the themargins andinterspaces ofthetextas opentoannoartificial fieldin important rectangular respects;their tation.It is clearthatthesenseofthewholedependson solidfilling ofthebackground reflects thepictures they habitsofseeingwhichmayvary.A Chineseartist, senhaveseen; and theirchoiceof colorspresupposesan sitiveto thesmallestinflection ofa brushstroke andits adult'spalette,a systemof tonesacquiredthrougha placeinthepicture, is notdisturbed bythewriting and longexperience ofrepresentation. The remarkable ex- sealsaffixed totheoriginal work.He no moreseesthem in our zoos should as partsofthepicturethanwe seea painter'ssignature pressionsof the monkey-painters fromthispointofview.It is we who inthelowerpartofa landscapepainting alsobe considered as an objectin elicitthosefascinating resultsby puttingpaper and theforeground of therepresented space. In Assyrian in art,too,whichalreadypossesseda preparedand encolorsinthemonkey's hands,justas wegetmonkeys thecircusto ridea bicycleand to perform otherfeats closedground, therepresented bodiesofkingsandgods withdevicesthatbelongto civilization. No doubtthat weresometimes incisedwithwriting thatcrossedthe themonkey's as an artistdisplaysimpulsesand outlinesofthefigures. activity reactions thatarelatentin hisnature;butlikehisselfIn a reverseorderand fromothermotivesartistsin resulton ourowntimepreserve on wheelstheconcrete onthepaperorcanvastheearlier balancingadjustment itappears,is a productof linesand touchesof colorwhichhave been applied paper,howeverspontaneous whichmeans,ofcourse,theinfluence in theprocessofpainting. of successively domestication, Theyadmitat a culture.It is an experiment thata civilizedsociety leastsomeofthepreparatory andoftententative forms ina sense,with as a permanently visibleand integrated makeswiththeanimalas itexperiments, partof the the childin elicitingfromhimthespeechand other image;thesearevaluedas signsofthemaker'sactionin habitsofhiscommunity. producing thework.We understand thisas another aim The character oftheoldestimage-fields thatweknow thantheoverlayofimageon imagein prehistoric art; -untreated and unbounded-is not just an archaic butit is worthnotingas thesourceofa similarvisual of thepast. If it seemsto us naturalto effectreachedfroman altogether phenomenon different pointof createa smoothdelimitedgroundfortheimageas a view.I havenodoubtthatthemodernpractice disposes of clearperception, worksas a beautiful necessity we mustrecognize, collective too, us to see theprehistoric thecontinued useofthemoreprimitive groundinlater palimpsest. Modernart,sincetheRenaissance, culturesincludingour own. The wall-paintings of whileaimingata in Egypt(ca. 3500 Bc) recallin their stricter Hierakonpolis unityof a picture-a unitythatincludesthe of thefigureand thereservedshapesof the scattered unboundedgroupsthecaveand rockimages interplay also examplesofthedeliberately made oftheOld StoneAge;andmanyprimitive peoplescon- ground-offers tinueto drawand incisetheirpictureson untreated, fragment or sketchas wellas incomplete workthatis unenclosedsurfaces.The spontaneousgraffiti on the prizedforqualitiesoftheunfinished state,andeventhe ofa smallpartofthefieldwithout wallsof ancientRomanbuildingsare,in thisrespect, painting regardtothe notdifferent fromthosedrawntoday;likethemodern voidsaroundit. It is possiblethattheunprepared onestheydisregard thefieldtheyhaveusurped,even groundhada positive an of the defacing existing picture.Butthefield image meaningfortheprehistoric painter,butthisidea is notalwaysinviolateevenin a workpreserved with mustremainhypothetical. One can supposethatthe as a preciousobject.In Chinawherepainting artistidentified reverence withtherockor cavethrough thepriwas a noblearttheownerdid nothesitateto writea mordialroughnessof the groundof his picture.A commentin verseor proseon the unpaintedback- modernartist, JoanMiro,whoprobably knowstheold groundof a sublimelandscapeand to stamphis seal rockpaintings ofhisnativeandcherished Catalonia,has on thepicturesurface.The groundofthe feltthe attraction of the irregular surfaceof the enprominently imagewashardlyfelttobe partofthesignitself;figure duringrockand used itas a groundon whichto paint On someproblemsin thesemiotics ofvisualart I I hisdirectly conceivedsign-like abstractforms.Others tobemoreformally presented andcomplete andtoexist have paintedon pebblesand on foundfragments of ina worldofitsown. naturaland artificial objects,exploiting theirregulari- More recently paintings havebeenhungaltogether tiesofthegroundandthephysiognomy oftheobjectas unframed. The frameless modernpictureexplainsin a oftheframeinolderart.The frame partofthecharmofthewhole.But I inclineto think sensethefunctions thattheprehistoric surfacewasneutral, a stillindeter- wasdispensable whenpainting ceasedtorepresent deep minatebeareroftheimage. spaceand becamemoreconcerned withtheexpressive Besides the preparedgroundwe tend to take for and formalqualitiesof the non-mimetic marksthan grantedtheregularmarginand frameas essentialfea- withtheirelaboration intosigns.If thepaintingonce turesoftheimage.It is notcommonly realizedhowlate recededwithin theframed space,thecanvasnowstands is theframe.It was precededbytherec- outfromthewallas an objectin itsownright,witha an invention as tangibly tangularfielddividedintobands; the horizontals paintedsurfacewhether ofabstract themesor the witha representation and supporting groundlinesor stripsconnecting whichis predominantly flatand weremorepronounced figures visuallythanthesepa- showstheactivity oftheartistin thepronounced lines itwaslatein and strokesor the higharbitrariness ratevertical edgesofthefield.Apparently of the selected the second milleniumBC (if even then) beforeone formsand colors.Althoughit is in keepingwiththis thoughtof a continuousisolatingframearoundan aspectofmodernpainting, theunframed canvashasnot likea citywall.When becomeuniversalevenfornew art.But thestripsof enclosure image,a homogeneous salientand whenenclosingpictureswithperspective woodor metalthatnowframemanypaintings are no ornamented enclosures that backintodepth longerthesalientandrichly setsthepicturesurface views,theframe andhelpsto deepentheview;itis likea windowframe oncehelpedto accentthedepthofsimulatedspacein of theideaofthepreciousness throughwhichis seen a space behindtheglass.The thepictureandconveyed framebelongsthento thespaceoftheobserverrather theworkofartthrough itsgildedmount.Theyarethin oftenflushwiththeplaneofthecanvas, thanoftheillusory, three-dimensional borders worlddisclosed discreet device and in theirsimplicity withinand behind.It is a finding and focussing theyassertalso therespectfor inthepracticeoftheart.Withandintegrity placedbetweentheobserverand the image.But the frankness thepainting frame and mayenteralsointotheshapingofthatimage;and outa frame, appearsmorecompletely in- modestly thecontrasts theartist'swork.A parallelto theframeless notonlythrough andcorrespondences is themodernsculpture cited by its strongform,especiallyin architecturalpainting without a pedestal;it butalso,as in modernstyles,in thepractice is eithersuspendedorplaceddirectly on theground. sculpture, theforeground ofcutting objectsoddlyat theframeso Our conception oftheframeas a regularenclosure thattheyappearto be close to theobserverand seen isolating thefieldofrepresentation fromthesurroundfrom anopening.Byintercepting thesidethrough these ing surfacesdoes not applyto all frames.There are inwhichelements objectstheframeseemstocrossa represented fieldthat pictures andreliefs oftheimagecross extendsbehindit at the sides.Degas and Toulouse- theframe, as iftheframewereonlya partofthebackLautrecwereingeniousmastersof thiskindofimagery. groundand existedin a simulatedspace behindthe A relatedmodernpractice:thecroppedrectangular figure. oftheframe Suchcrossing is oftenan expressive without frameor margin, as movingappearsmore picture, helpsus to see more device;a figurerepresented now activein crossingthe frame,as if unboundedin his clearlyanotherroleoftheframe.Such cropping, in books and motion.The framebelongsthenmoreto the virtual illustrations commonin photographic and the the out magazines, brings partial, fragmentary spaceoftheimagethantothematerial surface;theconis the main in the even where vention an the is naturalized as element of contingent image, object picturespace isolated ratherthanoftheobserver'sspaceor thespaceofthe centered.The pictureseemsto be arbitrarily intotheob- vehicle.In medievalartthisviolationof theframeis froma largerwholeand brought abruptly server'sfieldofvision.The croppedpictureexistsas if common,but thereare examplesalreadyin classical butas a forhismomentary glanceratherthanfora setview.In art.The frame appearsthennotas an enclosure withthistype,theframedpictureappears pictorial milieuoftheimage.Andsinceitmayserveto comparison 12 MEYER SCHAPIRO enhancethemovement ofthefigure, wecanunderstand severalfigures arepresented; thentheintervals between an oppositedevice:theframethatbendsand turnsin- themproducea rhythm ofbodyandvoidanddetermine wardintothefieldofthepicture tocompress orentangle effects ofintimacy, encroachment andisolation, likethe thefigures (thetrumeau ofSouillac,theImagoHominis intervals ofspaceinan actualhumangroup. in theEchternach Gospels,Paris,Bibl. Nat. ms. lat. The sameproperties of thefieldas a space witha 9389). latentexpressiveness are exploitedin printedand Besidesthesevariantsof theframe-field relationin paintedverbalsigns.In thehierarchy ofwordson the artI mustmention anotherthatis equallyinteresting: titlepageofa bookorona posterthemorepotentwords theframeis sometimes an irregular formthatfollows are notonlyenlargedbut oftenisolatedon a ground theoutlinesoftheobject.It is no longera pre-existingwhichis moreopenat thesides. feature oftheimage-vehicle orgroundbutanaddedone It is clearthatthepicturefieldhas local properties thatdependson thecontents oftheimage.The image thataffect oursenseofthesigns.Thesearemostobvious comesfirst and theframeis tracedaroundit.Herethe in thedifferences ofexpressive qualitybetweenbroad frameaccentstheformsof thesignsratherthanen- andnarrow, upperandlower,leftandright, central and closesa fieldon whichthesignsareset.As intheexam- peripheral, thecorners andtherestofthespace.Where ples wherethe figureburststhroughthe frame,the thereis no boundaryofthefield,as in cave paintings independence andenergy ofthesignareassertedinthe andunframed imageson rocksorlargewalls,wecenter detoursforcedupontheframebytheimage(Vezelay). theimageinourview;intheboundedfieldthecenteris We learnfromtheseworksthatalthough thestrictly predetermined bytheboundaries orframe andtheisoframeseemsnaturaland satisfies latedfigureis characterized enclosing rectangular in partbyitsplacein the a needforclarity in isolating theimagefortheeye,itis field.Whenstationed inthemiddleithasanother quaonlyone possibleuse of theframe.The formcan be lityforus thanwhensetat theside,evenifbalanced variedto producequite oppositeeffects, whichalso thenbya smalldetailthatadds a weightto thelarger someneedor concept.All thesetypesareintel- void.A visualtensionremains, satisfy and thefigure appears ligibleas devicesofordering andexpression, butnoone anomalous, evenspiritually displaced, strained; yetthis ofthemis necessary or universal. Theyshowthefree- appearancemaybe a deliberately as soughtexpression inarbitrarily domofartists devia- ina portrait effective constructing byMunchinwhichtheintroverted subject tionsfromwhatmightappearatfirst tobe inherent and standsa littletothesideinan empty is space.The effect all thestronger immutable a prioriconditions sincetheself-constrained ofrepresentation. postureand Let us return totheproperties ofthegroundas a field. otherelementsof theimageworkto reinforce an exofthebrooding AlthoughI haveused theword"neutral"to describe pression andwithdrawn. The tendency theuntreated itmustbe saidthattheunpainted to favoran off-center surface, positionhas beennoticedin the ofemotionally emptyfieldarounda figureis not entirely devoidof drawings disturbed children. effect evenin the mostcasual unbounded The qualitiesofupperand lowerareprobablyconexpressive representations. on thenarrow nectedwithour postureand relationto gravity Imaginea drawnfigure and thatconfines himbetween perhapsreinforced spaceofa pieceoffieldstone by our visualexperienceof earth on and sky.The difference can be illustrated edgesclosetothebody;andimaginethesamefigure by theuna broaderthoughstillirregular of a wholewithsuperposedelementsof surface.In thefirsthe invertibility willappearmoreelongated inthesecond unequalsize(see diagram). andcramped, he standsin a spacethatallowshimmorefreedom of movement and suggeststhe potentialactivityof the A body.The spacearounditis inevitably seennotonlyas butalso as groundin thesenseof Gestaltpsychology, B to thebodyandcontributing toitsqualities. belonging For theaesthetic eyethebody,and indeedanyobject, seemstoincorporate theempty B spacearounditas a field A ofexistence. The participation ofthesurrounding void intheimage-sign ofthebodyis stillmoreevidentwhere ofvisualart On someproblemsin thesemiotics 13 with artat an earlystage.Thereareexamplesin whichleftThoughformedof thesamepartsthe rectangle directions coexistinthesamework notthesameas the wardandrightward smallA overlargeB is expressively thescenesto is non- ofnarrative one withthesameB overA. The composition imagery;theyaccommodate ora liturgical focus,as inthe symmetry as architectsrecognizein designinga an architectural commutative, Nuovoin holdsforsingleelements;the mosaicsonthetwonavewallsofS. Apollinare faSade.The sameeffect totheEast advancing figures cubistpainter,JuanGris, remarkedthata patchof Ravennawithprocessional visualweightin theupperand end,whiletheGospelscenesabovethemproceedfrom yellowhas a different andrightin judging EasttoWest.Withineachseriesleft-to-right lowerpartsofthesamefield.Nevertheless, havean identicalgoalandconnotation. in orderto to-left theirwork,artistsofteninvertthepainting in boustrophedon One can findalso representations of formsor colors,theirbalance see therelationships ina second andreturning left-to-right to theobjectsrepre- order,beginning withoutreference and harmony, fromrighttoleft(ViennaGenesis). of register abstraction sented.But thisis onlyan experimental is thesequencefromtop ofconvention Less a matter of judgedin a scrutiny one aspect;theunityis finally scenes.The orien- to bottomin seriesofextendedhorizontal (ornon-mimetic) theworkinitspropermimetic vertical sequenceof tation.However,abstractpainterstodaydiscovernew sameordergovernsthedownward from whichmustbe distinguished writing, even a preferred horizontal throughthatinversion, possibilities orderofthesignsin ChineseandJapanese form.The late FernandLegerconceivedas a goal of thevertical and of thesinglelettersin certainGreekand paintingan imageequallyvalidin all posi- writing figurative CE. on pictures afterthe6thcentury tionsoftherotatedcanvas;thisideainspiredhispaint- Latininscriptions with field superposed oftheupperpartofa seenfromabove,andhas The priority ingsofdiversandswimmers, is nota strictrule,however.One can representations in a floormosaic. an obviousapplication ofchurches on doorways play pointto medievalsculptures callsintofuller ofmovement The representation thelower from sequenceproceeding withrespecttoqualitiesofthedifferentwitha narrative a cryptesthesia this works ina field.We livemoreinthehori- panelsupwards(Moissac,Verona).In some axesanddirections climactic where the the motivated order is content; by thantheverticaland we arenotsurzontaldimension seriesis thefinalone,as in imagesof prisedto learnthatthesamelinelooksshorterwhen sceneina vertical The feltspaceofevery- thelifeofChrist,it willbe placedat thetop.One may thanwhenvertical. horizontal thoughwelearntousethe note,too, thatwe see a verticalline or a columnas is anisotropic dayexperience metricpropertiesof an objectiveuniformspace in movingupwards. ofdirection mayarisealsoforthesingle The problem physicalobjectsto eachother. accommodating in profile ifit is presented isolated particularly in figure, and is offigures movement Whererepresentation is the in A example action. familiar in whether at rest or be extended of successiveepisodes,theimagemay in When relief and painting. figure like striding to be read Egyptian which have bands broadandsuperposed in theroundsucha figurealwaysstands in represented direction text.There is thena prevailing a written ofthisrulesugthe left as a with the legadvanced;therigidity if to are even eye given they certainpictures, meaning. geststhatthe posturehas a conventional whole. simultaneous a superon of the left the choice Whether depends leg it arises conventional; such is not Directednessas on some in or the first stition marching step concerning and the represented of objects nature from thetransitive transwhen cannot natural I However, say. disposition, in of order of time an an order expressing thetaskof choice ofleg or the field of posed to the relief, painting in successive directedness of space. The requirement oftheprofiled bythedirection Though toadvanceis determined scenesadmitsa choiceofdirection. contiguous if theleftlegis brought forward; choice,for body;ifitfacesright, itisnotanarbitrary itbecomesa convention, chosena good itfacesleft,itis therightlegthatis advanced.In both in thedirection we sometimes recognize pointofview, leg,fromtheobserver's orartistic problem.The varying cases,thefarther solutionofa technical Thisprinciple movement. andevenofdown- istheonechosentorepresent orright-to-left ordersofleft-to-right the in pictorialart,as in writing, maybe reconciledwiththestrictrulegoverning wardverticalalignment in theroundbyourassumingthatthelatterwas ofthe figure wereprobablydetermined byspecialconditions field,thetechnique,and thedominantcontentof the conceivedfromhis rightside; he facesand moves I14 MEYER SCHAPIRO in which,fromtheobserver's the viewpoint, and hencehis leftleg,as thefarther rightward leg,is sentation left part of the picture surface is the carrier of the advanced.2 inthefield,whichis also values.Thisreversal In thestationary isolatedfigure, unconditioned bya preferred in themirror, is a goodexample thepredominance oftheleftprofile thatoftheself-image controlling context, thatmayarisebetweenthequalitative hasbeenexplainedbya physiological fact.The leftward of theconflict ofthefield,whether inherent oracquired,and profile ofthehead,itis supposed,owesitsgreater fre- structure objects.In theMiddleAgesone quencyto theeasiermovement (pronation) ofthear- thatoftherepresented of the variablepositionsof tist'srighthandand wristinward,i.e., to theleft,as debatedthe significance appearsalso in thefreehand drawingofcircles:right- Peterand Paul at the leftand rightof Christin old handedpersonsmostoftentracethe circlecounter- mosaicsin Rome (PeterDamian). Wherethereis no centralfigure clockwise and left-handed, towhichleftandrightmustbe clockwise. (See theworkof dominant referred, theviewer'sleftandrightdetermine Zazzo on children's drawings.) bydirect ratherthanbyreflection, But oftenan internal contextdetermines one or the translation, theleftandright in profile otherdirection a peculiarity ofone ofthefield,justas inactuallife.In bothcasestheparts portraits; sideofthefaceoftheportrait signs;butthefieldis opento subjectis enoughtolimit ofthefieldarepotential the choice. Wherethe artistis freeto choose any reversal in submitting to an orderofvaluesin theconpositionof the face,the particular profileis selected textoftherepresented objectsor in thecarrierof the image. becauseofsomevaluedqualityfoundin thisview. on theconventional, Theseobservations thenatural, The lateralasymmetry ofthefieldmaybe illustrated thefreely chosenandthearbitrary intheuseofleftand byanotherpeculiarity ofpicturesand ofbuildings.If rightin theimagefieldbringsus to a largerproblem: wepairtwoforms, onetall,theothershort(as inthediawhether theleftandright sidesofa perceptual fieldhave grambelow),reversal alterstheirappearance noticeably. different hasgrownup inherently qualities.A literature on thesubject,someauthorsaffirming thattheunlike of the two sides are bioqualitiesand irreversibility of the logicallyinnateand arisefromtheasymmetry andespecially itshandedness; othersconnect organism themwithculturalhabitin readingand writing and a in space.A particular orientation dominant customary content thefeeling forleftandright mayalsoinfluence in images.We stilllack a comparative experimental ofpictures indifferent toreversal studyofthereactions cultures andespecially inthosewithdifferent directions in writing. tosemiotics Pertinent isthefactthatleftandright are alreadydistinguished sharplyin the signified objects themselves. Everyoneis awareofthevitalimportance of leftand rightin ritualand magic,whichhas influencedthemeaning ofthesetwowords, theirmetaphoricin everyday al extensions speechas termsforgoodand evil,correctand awkward,properand deviant.The ofthedeity'sorruler'srightsideinpictures significance and ceremony as the commonly, thoughnot univera represally,morefavored side,determines, however, 2 See HeinrichSchafer, Grundlagender lgyptischenRundbildnerei und ihre Verwandschaft mitdenender Flachbildnerei,Leipzig1923, p. 27. On someproblemsin thesemiotics ofvisualart I5 Likethevertically joinedunequalrectangles considered disturbor weakenthiseffect. Yet in thereversalof a earlier,thelateralgroupingis non-commutative. The picturenewqualitiesemergethatmaybe attractive to andin "A andB," wherethetwoelements differ decid- theartistandmanyviewers. edlyin size or formor color,is adjunctive, not conBesidesthesecharacteristics of the field-theprejunctive;and the positionin the fieldexpressesthis paredsurface, theboundaries, thepositions and direcrelation, justas thepairFatherand Son has a quality tions-we mustconsideras an expressivefactorthe lackingin Son and Father.If we grantthisdifference,format oftheimage-sign. theproblemis whether I meantheshapeofthefield,itsproporthedominance ofonesideinthe By format visualfieldis inherent or contingent. In asymmetricaltionsand dominant axis,as wellas itssize. I shallpass compositions offigures orlandscapesthechoiceofone overthe role of proportions and shape of the field, or theotherside forthemoreactiveor denserpartof whichis a vastproblem, andconsidersize. thepictureaffects theexpression;thereversalgivesa The size of a representation maybe motivatedin strangeaspectto thewhole,whichmaybe morethan different ways:byan external or physicalrequirement, theshockofreversal ofa familiar orhabitualform.Yet bythequalitiesoftheobjectrepresented. Colossalstait mustbe said thatsomegoodartistsin ourtime,like tues,paintedfigures thegreatlargerthanlife,signify theearlyengravers ofwoodblocks,havebeenindiffer- nessoftheirsubjects;andthetinyformat mayexpress entto thereversalof an asymmetrical in theintimate, thedelicateand precious.But size may composition theprinting ofan etchedplate,and havenotbothered also be a meansofmakinga signvisibleat a distance, to anticipateit by firstreversing the drawingon the apartfrom thevalueofthecontent, as onthefilmscreen plate.Picassohasoftendisregarded eventhereversal of andinthegigantic signsinmodernpublicity. Or a sign in theprint.It is an assertion his signature ofsponta- maybe exceedingly smallto satisfy a requirement of neity, madeallthemorereadily as thevalueofa drawing economy oreaseofhandling. (Thesedifferent functions orprinthascometobe lodgedinitsenergy andfreedom ofsizemaybe comparedroughly withthefunctions of andinthesurprise ofitsforms rather thanintherefine- volumeandlengthinspeech.)It is obviousthattheyare mentofdetailand subtlety ofbalance.One can doubt not unconnected;a colossalstatueservesbothfuncthattheartistwouldacceptthereversalofa carefully tions.We distinguish, atanyrate,twosetsofconditions in thesize of visualsigns:on theone hand,size as a composedpainting. ofvalueand as a function (I maynotehereas an evidenceofthesophisticated function ofvisibility; on the and acquiredin theperception of thedifferent visual otherhand,thesizeofthefieldandthesizeofdifferent qualityof the leftwardand rightward directionsin components oftheimagerelativeto realobjectswhich reversal ofcapitalN theysignify and relativeto eachother.A workmaybe asymmetrical wholes,thefrequent andS inthewriting adults. largelikea lengthy ofchildren andunpracticed picturescrollbecauseit represents These sametwoletters in early so manyobjectsallofaverageheight;oritmaybe small arealso oftenreversed medievalLatininscriptions. thedifferencelikea miniature andutilizethelimitedspaceto Apparently painting inqualityofthetwodiagonaldirections ofvalueinthefigures isnotenoughto expressdifferences bydifferences fixthecorrectone firmly in mindwithoutcontinued ofsize. motorpractice.) In manystylesofart,whereobjectsofquitedifferent How shallweinterpret theartist'stolerance ofrever- size in realityare represented in thesamework,they sal ifleftand rightare indeeddifferent in quality?In areshownas ofequal height.The buildings, treesand certain inarchaicartslooknolargerthanthehuman contexts thechoiceofthesupposedly anomalous mountains side maybe deliberatefora particular effect whichis figuresand sometimes smaller,and are therebysubreinforced If the ordinatedto them.Here valueor importance bythecontentoftherepresentation. is more sizethantherealphysical diagonalfromlowerleftto upperrighthas come to decisiveforvirtual magnitude I am notsurethatthisis a coun- oftheobjectsrepresented. possessan ascendingquality,whilethereversed forthedominance hasa descending an artistwhorepresents convention, ofthehumanfigure terpart over effect, figures ascendinga slopedrawnfromtheupperleftto theenvironment in the artof appearsindependently thelowerrightgivesthereby a morestrained, effortfulmanyculturesand amongourownchildrenin reprewill senting qualityto theascent.Reversalofthecomposition objects.One doesnotsupposethattheartistis i6 MEYER SCHAPIRO unawareoftherealdifferences insizebetweenmanand meanthatthe significance of the variouspartsof the theseobjectsofhisenvironment. The sizesofthingsin fieldandthevariousmagnitudes is arbitrary. It is built a pictureexpressa conception thatrequiresno knowl- on an intuitive senseofthevitalvaluesofspace,as exedgeofa ruleforitsunderstanding. The association of periencedin therealworld.For a contentthatis articsizeanda scaleofvalueis alreadygiveninlanguage:the ulatedhierarchically, thesequalitiesof the fieldbewordsforsuperlatives of a humanqualityare often come relevantto expressionand are employedand termsofsize greatest, highest, etc.,evenwhenapplied developedaccordingly. A corresponding contenttoday to suchintangibles as wisdomor love. wouldelicitfromartistsa similardispositionof the Size as an expressivefactoris not an independent spaceofa sign-field. Giventhetaskofmounting sepavariable.Its effect changeswiththefunction and con- ratephotographs ofmembers ofa politicalhierarchy in textof thesignand withthescale and densityof the a commonrectangular field,I haveno doubtthatsome image,i.e., withthe naturalsize of theobjects,their designerswouldhit on the medievalarrangement in numberandrangeoftypes;itvariesalsowiththesigni- whichthefounder is inthemiddle,hischiefdisciplesat fiedqualities.An interesting evidenceofthequalitative his sides,and lesserfigureswould be placed in the non-linear relationofthesize ofthesignto thesize of remaining spaces,above or belowaccordingto their thesignified objectis givenin an experiment: children relativeimportance. And it wouldseemto us natural whowereaskedtodrawa verylittlemananda bigman thatthephotographs areofa diminishing orderofsize firston a smalland thenon a largesheetof fromthecentertotheperiphery. together, thesmallman The relationofthesize ofthesignto thesizeofthe paper,enlargedthebigmanbutre-drew as beforeon thelargesheet. represented of objectchangeswiththe introduction In Western medievalart(andprobably inAsiatictoo) perspectivethechangeis thesamewhether thepertheapportioning ofspaceamongvariousfigures is often spective isempirical as inNorthern Europeorregulated in whichsize is corre- bya strictruleofgeometrical subjectto a scaleofsignificance as in Italy.In projection latedwithpositionin the fieldand withpostureand picturesafterthe I 5th centurythe size of a painted rank.In an imageofChristinMajestywiththe object, human or natural,relativeto its real size, spiritual theirsymbols, evangelists, and theprophets oftheOld dependson itsdistancefromthepictureplane.In conTestament(theBible ofCharlestheBald, Paris,Bibl. trastto the medievalpractice,perspective imposeda Nat.ms.lat. i), Christis thelargestfigure, theevange- uniform scale on thenaturalmagnitudes as projected listsaresecondin size,theprophetssmaller,thesym- on thepicturesurface.This was no devaluation ofthe bols are thesmallestof all. Christsitsfrontally in the human,as one mightsuppose;indeed,itcorresponded centerwithin a mandorla framed bya lozenge;theevan- toa further humanization ofthereligious imageandits gelistsin profileor three-quarters viewfillthequad- supernatural socialor spiritualimfigures. Greatness, rantsofthefourcorners;andtheprophets arebustsin portance,wereexpressedthenthroughothermeans the incompletelyframedmedallions that open at the fourangles of the lozenge between the evangelists.Of the foursymbols which are distributedin the narrow space between the prophets and Christ, the eagle of Johnis at the top, in accord withthe highertheological rankof thisevangelist;it is also distinguishedfromthe othersymbolsby carryinga roll,whiletheyhold books. Here it is evidentthatsize, employedsystematically, is an expressivecoefficientof the parts of the fieldas places ofthegradedfigures.In certainsystemsofrepresentation which depend on systemsof content the distinctivevalues of the different places of the fieldand the different magnitudesreinforceeach other.The fact thatthe use of thesepropertiesof the sign-spaceis conventional,appearingespeciallyin religiousart,does not such as insignia, costume, posture, illumination,and place in the field. In the perspectivesystemthe virtuallylargestfiguremaybe an accessoryone in theforeground and the noblest personages may appear quite small. This is a reversal of the normal etiquette of picturespace in which the powerfulindividualis often representedas a largefigureelevated above the smaller figuresaround him. It is a common opinion that the two systems,the hierarchicaland thegeometric-optical, are equally arbitraryperspectivessince both are governedby conventions. To call both kinds of picturesperspectivesis to missthe factthatonlythe second presentsin its scale of magnitudesa perspectivein the visual sense. The first is a perspective only metaphorically.It ignores the On someproblemsin thesemiotics ofvisualart '7 variations ofboththeapparent andtheconstant sizesof mediumor thetechnique,iftherepresentation offers objectsin realityand replacesthembya conventional theminimal cuesbywhichwerecognize thedesignated orderofmagnitudes thatsignify theirpowerorspiritual facethrough all itsvariations ofpositionandlighting in rank.The correspondence ofthesizesoftheobjectsin actuallife.The thickblackoutlineis an artificial equithesecondsystemto theirapparentsize in realthree- valentoftheapparentformofa faceand has thesame dimensional spaceata givendistancefromtheobserver relationto thefacethatthecolorand thickness ofthe is not arbitrary; it is readilyunderstoodby the un- outlineofa landmassin a maphas to thecharacter of trainedspectator sinceitrestson thesamecuesthathe thecoast.It wouldstilldenotethesamefaceforus, if respondsto in dealingwithhiseveryday visualworld. theimage-sign wereoutlinedinwhiteona blackground, The correspondence of thesizesof thefiguresin the justas a written wordis thesamein different colored hierarchical kindofpicturetotherolesofthefigures is inks. indeedconventional ina sense;buttheconvention rests forthepicture-sign, Distinctive however, is theperona naturalassociation ofa scaleofqualitieswitha scale vasiveness ofthesemantic evenwiththearbifunction, ofmagnitudes. To speakofAlexander as theGreatand trariness of thequalitiesof theimage-substance. The to represent himas largerthanhis soldiersmaybe a picture-sign seemstobe through andthrough mimetic, buttotheimagination convention; itis naturalandself- andthisis thesourceofmanymis-readings ofoldworks evident. ofart.Takenoutoftheimage,thepartsofthelinewill be seenas smallmaterial components: dashes,curves, I turnnowto thenon-mimetic elements ofthepicture dotswhich,likethecubesofa mosaic,havenomimetic thatmaybe calleditssign-bearing theimage- meaningin themselves. matter, All theseassumea value as substance ofinkedorpaintedlinesandspots.(In sculp- distinct signsoncetheyenterintocertain combinations, turethe distinction betweenthe modeledor carved andtheirqualitiesas markscontribute something tothe material andthesamesubstanceas a fieldraisesspecial appearance oftherepresented objects.According tothe problemsthatI shallignorehere.) context ofadjoiningorneighboring marks, thedotmay Withrespectto denotation whichis be a nail-head,a button,or thepupilofan eye; and a byresemblance, topictures as signs,theseelements specific haveproper- semi-circle maybe a hill,a cap,aneye-brow, thehandle tiesdifferent fromtheobjectstheyrepresent. Consider ofa pot,oranarch.Thereare,itistrue,ona represented as examplesthedrawnlineofthepencilorbrushorthe objectin a drawingor printmanylineswhichare not incisedlineproducedbya sharptoolinrepresenting the viewedas signsoftherealobjectanditspartsina morsameobject.Whilefromtheviewpoint thatfixeson the phologicalsense.The finehatching of thegreytones as a signeverypartofthislinecorresponds toa and shadowsin an engraving drawing corresponds to no such the partsof a network partof the objectrepresented-unlike on theobject.Yet whenseenat a properdiswordforthatobject fromtheaesthetic pointofview tance,it rendersdegreesof lightand dark,thesubtle andstrong contrasts thatbringoutthevoluthelineis an artificial ofitsown. gradations markwithproperties and illumination The artistandthesensitive oftheobject.Produced vieweroftheworkofartare me,modeling characterized by theirabilityto shiftattention freely by different techniques,the signsforthesequalities in theirsmalland largestructure fromone aspectto the other,but above all, to dis- mayvarygreatly and criminate and judge thequalitiesof thepicturesub- stillforma wholethatcorresponds to the sufficiently natural stancein itself. Onediscovers recognizable appearance. through ofexecution The blackness andthickness oftheoutlineofa repre- suchelements another aspectofsizeinthe thevariablescaleofcorrespondence. sentedfaceneednotcorrespond toparticular attributes image-signs, Just ofthatface.The samefacecanbe represented oftheirregularities in many as thesmallmapshowsnothing of belowa certain different ofthelines terrain thetechnicalwaysandwithquitevariedpatterns size,so ina picture meansofsuggesting orspotsthatdenotethefeatures. andillumination Theymaybe thickor artistic modeling There is in the thin,continuousor broken,withoutour seeingthese affectthe scale of correspondence. ofa realorimaginedface.The hatchedlinesa smallunitthatdoesnotrepresent qualitiesas peculiarities anyitsform,yetwhenrepeatedin picturewillalwaysbe recognizedas an imageof that thingbyitselfthrough facein different of thestyle,the greatnumbersin thepropercontextvividlyevokesa portraits, regardless I8 MEYER SCHAPIRO objects.A thickeroutlinemakesthe qualityoftheobject.On theotherhand,in therepresented particular fairlylargeelementshaveac- figurelook moremassive;a thinline can add to its paintings Impressionist aspect. An extensiveobject- delicacyandgrace;a brokenlineopenstheformto the quired a non-mimetic implion a smallfield,with playoflightandshadowwithalltheirexpressive space,a landscape,is represented a consequentincreasein therelativesize of theunits, cationsfortheconceptof things.In a corresponding inan Impressionist ofpigment i.e., relativeto thewholecomplexsignof whichthey waythevisiblepatching and ofluminosity tothegeneraleffect area part.In thepicturethepartsofthepaintedtree workcontributes andthemodern, theancient in shapeor color air.Bothpolesofsubstance, are fleckswithoutclearresemblance ofthewholeandconseemsto enterintothevisualmanifestation tothepartsoftherealtree.Herethepainting as wellas subtle ofoutlookandfeeling as a veypeculiarities approacha featureof verbalsigns.The tree-sign ofthesigns. itscontext; meanings as a tree,oftenthrough wholeis recognized the These variationsof the "medium"constitute butthepartsare hardlylikeleavesand branches.Yet no basicchangehas takenplace herein thesemantic poetryof theimage,its musicalratherthanmimetic hascho- aspect.But a greatmodernpainter,GeorgesBraque, relation ofimagetoobject.The Impressionist in poeticlanguage,has oftherealtree havingin mindthefigurative appearance a particular sentorepresent objectsin the oftherepresented as iffused spokenparadoxically partslookindistinct inwhichtheanatomical Wecanunderas thepoetry ofpainting. objects.They stilllifepicture witheach otherand withneighboring hisownwork.We areoften through thingsveiled standthisremark innatureas distant havebeenexperienced in makingthestronglyoflightand color charmedbyhis inventiveness and as variations bytheatmosphere of paintedlines,spotsand colors visiondiscernssuch markedstructures rather thanas shapes.Perspective ways;and thetoneandcon- assumetheaspectofobjectsin unexpected thebroadsilhouette, objectsthrough carriers as the hisobjectsappear surprising details.Thoughtheydo conversely text,withoutdiscriminating or of form. sourcesoforiginalpatterns spotsofcolorinthe objects,certain resemble notclearly are Iftheelements ofthevehicleandtheirproperties and someoftheseare to sensations, imagecorrespond formal the of intimate its roots of the aesthetic of work, notofthelocalcolorsofobjectsbutareinducedcontrast structure and expression, theyowe theirdevelopment ofillumination. colorsandeffects and in to variety greatpart theirservicein representatoanotheraspectorcontent It is thisshiftofinterest In abstractpainting thesystemofmarks,strokes tion. thearbitrariness ofreality thatled paintersto criticize and distribuand and certain ofcombining ways spots everyinflecalthough entity, oftheoutlineas a distinct forarbithem on the field become available have a knownand recognizable ting tionof theline represents as of the use without correspondence requirement of scienwiththesupport trary partofitsobject.In asserting abstracted The forms that result are not simplified we in and that see signs. only tiststhattherearenolines nature thevisibleworld formsof objects;yetthe elementsappliedin a nonto represent colors,theyundertook wholeretainmanyofthequaliuninterpreted without defin- mimetic, color of patches moretruly byjuxtaposing mimetic ties and formal ofthepreceding relationships truer if was defended as their system But ingoutlines. those is overlooked art. This connection by if into important it introduced to the semblanceof thingsand or a kind of ornament who abstract as painting regard as of nature such for aspects new signs picture-making stateofart.Impressionist to a primitive ofcolorsthat as regression andtheinteractions lightandatmosphere in whichthepartshavebeenfreedfromthe intheolderstyles,itrequired painting, couldnotbe represented tothepartsofanobject, too,andonethatinseveralfeatures ruleofdetailedcorrespondence a picture-substance as thearchaicblackoutline-I meanthe is alreadya step towardmodernabstractpainting, is as arbitrary of artistsfoundImgeneration ofpaintand thereliefofcrusty thoughthefollowing visiblydiscretestrokes toorealistic. and texture pressionism whichviolateboththecontinuity pigment Thesearematerial-techni- I havenotedseveralwaysin whichthegroundand oftherepresented surfaces. fieldfortheelements as a non-mimetic conceived thanthe frame, oftheimageno lessarbitrary cal components their affect theirmeaningand in particular andtheEgyptians. ofimagery, firmblackoutlineoftheprimitives sense. as everyartist expressive The qualitiesoftheimage-substance, the farI wish,in conclusion,to indicatebriefly separatefromthequalitiesof knows,arenotaltogether On someproblemsin thesemiotics ofvisualart I9 reaching conversion ofthesenon-mimetic elements into artthisallusiontoan actualboundedfieldofa spectator Theirfunctions in represen- was mostoftenmadeby representing positiverepresentations. withinthepicofexpression and ture-field tationin turnlead to newfunctions itselfthest-able enclosing partsofan architecorderina laternon-mimetic art. constructive ture-doorwaysand windowledges thatdefineda The groundline,thickened intoa bandand colored realand permanent frameof visionin thefieldof the becomesan elementoflandscapeor archi- signata. separately, tectural space.Its upperedgemaybe drawnas an irreThe conception ofthepicture-field as corresponding a terrain ofrocksand in itsentirety a horizon, gularlinethatsuggests to a segmentof spaceexcerptedfroma hills. largerwholeis preserved inabstract painting. Whileno ornament longerrepresenting The uniform background surface, through objects,Mondrianconstructed a linesof unequalthickora colorthatsetsitoffsharplyfromthegroundband, gridof verticaland horizontal ofwhichsomeareincomplete, willappearas a represented wallorenclosureofspace. ness,forming rectangles theinter- beingintercepted ofperspective, Finally,bytheintroduction by theedge of thefield,as Degas' become figures are cutby theframe.In theseregular,though valsofthepicturesurfacebetweenthefigures weseemtobehold three-dimensional forms signsofa continuous spaceinwhich notobviously commensurable, the extended owe theirvirtualsize,theirforeshort- onlya smallpartofan infinitely thecomponents structure; oftherestis notdeduciblefromthefragmenenedshapes,theirtonalvalues,to theirdistancefrom pattern thetransparent pictureplaneandtheeyeofan implied tarysamplewhichis an odd and in somerespectsambalance observer. biguoussegmentand yetpossessesa striking of andcoherence. In thisconstruction intoan element onecanseenotonly The boundary, too,is transformed It maycut theartist'sidealoforderandscrupulous but as I havealreadyremarked. representation, precision, the atthesidesbutalsoaboveandbelow, alsoa modelofoneaspectofcontemporary figures, especially thought: oftheworldas law-boundintherelation of in sucha wayas to represent therealboundariesofa conception visionoftheoriginalscene.The simple,elementary proximate spectator's components, yetopen,unbounded as a whole. which andcontingent boundarythenis likea windowframethrough oneglimpses onlya partofthespacebehindit.In older

© Copyright 2026