Resource Alignment Review - Monterey Bay Teachers Association

Resource Alignment Review Monterey Peninsula Unified School District Prepared By: Ann Hern Jannelle Kubinec Dr. Barry R. Groves Maria Phillips January 2015 WestEd — a national nonpartisan, nonprofit research, development, and service agency — works with education and other communities to promote excellence, achieve equity, and improve learning for children, youth, and adults. WestEd has 17 offices nationwide, from Washington and Boston to Arizona and California, with its headquarters in San Francisco. For more information about WestEd, visit WestEd.org; call 415.565.3000 or, toll-free, (877) 4-WestEd; or write: WestEd / 730 Harrison Street / San Francisco, CA 94107-1242. © 2015 WestEd. All rights reserved. Table of Conttents Executtive Summ mary ............................................................................................... 1 Introdu uction ............................................................................................................ 3 ogy .............................................................................. 3 Approa ach and Methodol M Finding gs and Recommendations......................................................................... 4 Conditions Affecting Ressource Alig gnment ............................................................... 6 Expe enditure Analysis...................................................................................................... 8 C Comparison ns to Other Districts .......................................................................................... 10 Prac ctices to Su upport Alig gnment ............................................................................... 13 Siite and Fed deral Fundin ng Allocatio ons .............................................................................. 15 Tiitle I ....................................................................................................................................... 16 Elligibility ................................................................................................................................. 16 D Distribution ............................................................................................................................ 17 U Uses ........................................................................................................................................ 18 C Carryover .............................................................................................................................. 19 Title II and III .................................................................................................................. 19 Summa ary of Find dings ........................................................................................... 19 Recom mmendatio ons and Options O to o Consider.................................................. 20 Executive Summary With respect to its budget and leadership, 2014-15 was a year of many firsts for the Monterey Peninsula Unified School District (District). The school year began with a new superintendent and several new cabinet-level staff. This was also the first year the District operated under California’s Local Control Funding Formula with net growth in funding following several years of no change or drops in funding. The Board of Education also established the first District Budget Advisory Committee (DBAC) to advise the District’s leadership regarding strategic priorities and investments. The District requested that WestEd provide a review and analysis of its budget and related systems to address specific DBAC recommendations and provide an assessment and recommendations for improving how resources are used and aligned to meet current and emerging goals, objectives, and desired outcomes for students. This review also provides recommendations that identify opportunities to optimize how resources are aligned to improve student outcomes and, very importantly, to assist the District in determining whether and how to best implement recommendations identified in the review. As one of several studies commissioned by the District, this review considers findings and recommendations included in the District’s 2014 Curriculum Audit to ensure consistency and coherence. This report can be used by District leaders and the DBAC to inform changes to the District’s culture, policies, and processes that take advantage of the state’s increase in funding and flexibility to address locally determined needs. The District starts with a relatively sound foundation for budget management, which situates it well to make changes that result in routines and processes that evidence strategic alignment of resources. Following are key findings from this review: The District’s budget assumptions for 2014-15 appear to be reasonable, but there is a history of the ending fund balance increasing between what is estimated at budget adoption and what the actual amount is when the District’s fiscal year is closed in September. The District has similar expenditure patterns for certificated salaries, materials and supplies, and contracted services, but the classified and employee benefit expenditures are higher and teacher salary profiles is lower than expected when compared to districts in the comparison group. The District has a budget development system in place, but it appears that financial performance rather than student performance has been the primary driver. The District’s 2014-15 LCAP reflects that a significant investment of supplemental and concentration funds (25%) will be allocated to sites to serve the unique needs of students. The District has the opportunity and responsibility to build capacity amongst site level leadership on how to better align site level resources to support improving student outcome. 1 The report offers the following recommendations: Develop a clear vision for instruction within Monterey Peninsula Unified School District to add depth to existing goals and actions. For the District to support resource alignment, a clear vision for instruction must be present around which goals, initiatives, and actions can be aligned. As this begins to emerge, deliberate attention should be given to instituting management practices that reinforce resource alignment. Use regular Executive Cabinet meetings and time with site administrators to improve resource planning, adherence with budget procedures, and progress monitoring. The District may want to consider creating a standing resource alignment item for its strategically oriented cabinet and site meetings with a clear agenda for the year as to how this strand of dialogue will contribute to evidence of improved practice. Revise or eliminate the eight period day. The District’s curriculum audit identified concerns regarding the effectiveness of the eight period day, which merit consideration. The District should consider the cost-effectiveness of this approach as it assesses how it aligns resources to strategic priorities. Complete a more in-depth study of the Special Education Program to identify practices that contribute to unpredictable costs and overall costs of the program, and those that impair or contribute to program quality. Improvement alignment of classified staff to District priorities and needs. As the District increases its investments in positions it should carefully current classified staffing levels and structures to ensure that existing and new positions are in alignment with the District’s strategic objectives. Transition the work of the District Budget Advisory Committee to support LCFF and LCAP planning. 2 Introduction With respect to its budget and leadership, 2014-15 was a year of many firsts for the Monterey Peninsula Unified School District (District). The school year began with a new superintendent and several new cabinet-level staff. This was also the first year the District operated under California’s Local Control Funding Formula with net growth in funding following several years of no change or drops in funding. The Board of Education also established the first District Budget Advisory Committee (DBAC) to advise the District’s leadership regarding strategic priorities and investments. The DBAC made several recommendations including: Recommendation A: Study spending compared to similar sized districts with similar English Learner populations. Recommendation B: Analyze Unrestricted Expenses for MPUSD for three years and comparable districts, 2011-12, for specific observations. Recommendation C: Implement a zero-based budget process as soon as possible for the 2015-16 school year. Recommendation D: Consider programs and positions on the Priority List in the stated order of importance when budgeting decisions are made. The District requested that WestEd provide a review and analysis of its budget and related systems to address specific DBAC recommendations and provide an assessment and recommendations for improving how resources are used and aligned to meet current and emerging goals, objectives, and desired outcomes for students. This review also provides recommendations that identify opportunities to optimize how resources are aligned to improve student outcomes and, very importantly, to assist the District in determining whether and how to best implement recommendations identified in the review. As one of several studies commissioned by the District, this review considers findings and recommendations included in the District’s 2014 Curriculum Audit to ensure consistency and coherence. This report can be used by District leaders and the DBAC to inform changes to the District’s culture, policies, and processes that take advantage of the state’s increase in funding and flexibility to address locally determined needs. The District starts with a relatively sound foundation for budget management, which situates it well to make changes that result in routines and processes that evidence strategic alignment of resources. Approach and Methodology This review focused on how the District allocates its resources to support its vision for providing high quality instruction and student support. Effective resource alignment ensures that resources are directed to support indentified needs through quality programs, services, and actions that are focused on District goals and priorities. An important function of this review is to provide the District’s superintendent and leadership with a strategic analysis of budget information and context to address improvements in resource 3 alignment. The review includes consideration of how the District’s current allocation plans/formulas, policies, procedures, and structures impact the alignment, availability, effectiveness, and efficiency of resources. Information and feedback was gathered through interviews with the superintendent, cabinet members, and site leaders. In addition, policies and procedures, as well as fiscal and program data available from the District and the California Department of Education (CDE), were reviewed. This report includes references to comparison districts, which were selected based on their similarities in size, grade levels served, percentage of English learners and academic performance. Figure 1 provides an overview of the selected comparison districts. Figure 1: Comparison Districts District Name Azusa Unified Kings Canyon Joint Unified Lompoc Unified Woodland Joint Unified Los Banos Unified San Jacinto Unified Monterey Peninsula Unified Pittsburg Unified 9,566 % English Learners 32.0% % Free/ Reduced Meals 84.9% 96.2% Academic Performance Index (API) 736 % Schools Meeting API Target 5.9% 9,879 33.1% 80.0% 89.7% 783 30.0% 9,914 23.1% 64.8% 73.2% 772 18.8% 9,991 27.7% 68.5% 75.1% 767 35.7% 10,065 30.3% 74.6% 84.8% 762 16.7% 10,301 22.6% 77.9% 82.6% 754 35.7% 10,768 30.5% 62.9% 77.9% 763 25.0% 10,769 33.2% 84.3% 94.1% 738 33.3% Enrollment % Minority Note: All data is from EdData. Enrollment and demographic data is from 2013-14, and academic performance data is from 2012-13.1 Enrollment includes charter school enrollment. Findings and Recommendations As noted earlier, the District has commissioned several studies to inform strategic planning and improvement. Among these studies is a curriculum audit, which included a review of budget practices. This review and report complement the curriculum audit by focusing on how the District can align human and financial resources to support and evidence its goals and vision. Aligning resources includes using strategic planning methods to optimize the impact of allocation plans. Creating sustainable allocation plans includes establishing operational policies and procedures to support the plan. Effective resource alignment ensures that resources are directed to support indentified needs through quality programs, services, and actions focused on District goals and priorities. 1 2012-13 is the most recent year for which statewide data are available. While funding levels have increased since this time because the comparison districts share similar demographics such increases remain somewhat comparable and support the relevant use of this comparison group for the purposes of this report. 4 Following are findings included in the curriculum audit that have bearing on resource alignment and which have been substantiated in this review: Information provided consistently pointed to a process that represents traditional, prioryear rollover budget planning with minimal guidelines for prioritization of requests and needs-driven modification in response to data and program planning. The practice of continually revising allocations during the operational year was found to be detrimental to the stability in planning for educational programming. It is challenging to identify the costs for a specific program to inform assessment of impact and future planning. The District has had substantial variances in the amount it estimated in initial budgets when compared to actual revenues and expenditures. The curriculum audit includes several criticisms of the level of precision and clarity of the District’s budget documents. While we agree that the District’s budget documents can be difficult to interpret and are subject to many cycles of revision, state requirements and structures for financial reporting contribute to the identified challenge. The curriculum audit identified six components of a curriculum-driven budget. In all but one area, priority setting based on input from district stakeholders, the District was deemed inadequate. Following are the five areas deemed inadequate: Tangible, demonstrated connections are evident between assessment of operational curriculum effectiveness and allocation of resources. Each budget request or submittal shall be described so as to permit evaluation of consequences of funding or non-funding in terms of performance or results of a given activity or program. Rank ordering of program components provided to permit flexibility in budget expansion, reduction, or stabilization based on changing needs or priorities. Cost benefits of components in curriculum programming are delineated in budget decision-making. Budget requests compete for funding based upon evaluation of criticality of need and relationship to achievement of curriculum effectiveness based upon concrete and valid data related to organizational quality. The curriculum audit reflects standards for performance aligned to exceptional practice. For the District to improve as the curriculum audit suggests, it must make incremental improvements in several areas including culture and leadership, structure and staffing, and overall procedures that support effectiveness and efficiency. In an effort to complement, and advance the findings from the curriculum audit, the findings are organized into the following sections: Conditions Affecting Resource Alignment. This section addresses factors such as budget and financial practices that may serve as constraints or facilitating factors to attend to resource alignment. 5 Expenditure Analysis. Understanding of current expenditures provides insights regarding areas of current alignment and opportunities for improved resource alignment as well as potential practices that may facilitate improvements. Practices to Support Alignment. This section describes current practices and how they can be transformed to make tangible improvements in the alignment of resources to goals and objectives for student outcomes. The findings and recommendations offered in this report are intended to serve as a resource to the District superintendent and leadership team as they work to build a district culture focused on student-level outcomes, a structure and staffing that aligns to this vision, and procedures and policies that ensure that work efforts are efficient and effective. Conditions Affecting Resource Alignment Local educational agencies faced the most challenging financial period of the past 50 years during 2008-13. Local educational agencies made budget reductions and relied on reserves (i.e., funding accrued from prior years) to accommodate the over 15 percent statewide reduction in funding. This period highlighted the importance of accurate budgeting and sound financial practices. There was little room for surprises or faulty adjustments. During the current transition from a period of decline in funding to one with much needed recovery and improvements, budget assumptions are critical to effective and efficient district management. Examples of key assumptions in a school district budget include, but are not limited to, the number of students (student counts are the primary driver of revenue), state funding levels, and compensation (both the numbers of employees and salary and benefit costs). When school districts adopt their budget, some assumptions are derived from known facts, such as the level of funding from the state. Others, such as student enrollment, are estimated based on prior trends and forecasting data. Budgets are created at the beginning of the fiscal year and are updated periodically throughout the year. To assess the District’s budget and financial management practices, we reviewed budget and financial information for the District’s General Fund for the fiscal years 2012-13, 2013-14, and the 2014-15 budget adoption. Below are the findings from this review: The unrestricted ending fund balance for 2012-13 decreased by approximately $4.7 million from the 2012-13 estimated actuals to the actuals as reflected in the 2013-14 adopted budget. It appears that most of the variation can be attributed to underestimating revenue and overestimating local contributions to restricted resources. Improvements were noted in the estimation of the unrestricted ending funding for 2013-14, with the difference from the estimated actuals to the actuals at approximately $1.4 million. The budget for unrestricted and restricted General Fund salary expenditures shifted significantly over the course of the 2013-14 budget from adoption to actuals. This is likely due in part to the implementation of the Local Control Finding Formula and the stipulated judgment agreement paid to Monterey Bay Teachers Association members. 6 The 2014-15 budget includes a significant increase, more than $3.2 million in local contributions. Such contributions are made from the unrestricted general fund to supplement specialized programs (i.e., special education, adult education). The District uses state revenue assumptions commonly used by local educational agencies. The District’s 2014-15 budget reflects such assumptions for state revenue with federal and local revenue estimated based on historical trends and grant/entitlement information. The District uses staffing allocations for certificated positions and for essential classified positions. The above mentioned practices conform with generally accepted and recommended practices. As noted above, state revenues for education are increasing after several years of decline. Modest increases were provided in 2013-14 and 2014-15. Furthermore, the District projects continued increase in its forecast for 2015-16 and 2016-17, which appear reasonable considering the Governor’s 2015-16 proposed budget. While statewide funding is increasing, positively affecting the District’s financial outlook, most funding provided to local education agencies is linked to student enrollment. Countering the overall growth in District revenues is a longstanding trend since 1994 of declining student enrollment. While the state provides a one-year reprieve from the negative effect that declining enrollment has on revenue, it does not provide any buffer for the many fixed costs that do not decrease in direct proportion to the loss of revenue. For instance, a decline of 60 students across a district will not reduce the need for facilities or operational costs, which creates a strain on remaining resources. Furthermore, the District has a history of deficit spending in the unrestricted General Fund and the current budget and multi-year projection reflect that this trend will continue. There is likely the opportunity to revise special education expenditure budgets, which will result in some reduction in total expenses for the program (see Expenditure Analysis section for more details). Similarly, the budget shows projects deficit spending from the restricted General Fund in 201415 and 2015-16. The 2014-15 restricted General Fund deficit appears to be due to planned spending of carryover balances such as Medi-cal and Common Core State Standards funding. This is consistent with state rules regarding the use of these funds. However, it important to note that carryover funds are one-time dollars and the sustainability of efforts funded with carryover funds need to be considered. As the District emerges from the prolonged period of fiscal downturn, now is the ideal time to evaluate policies and practices related to budget and financial management. It should be remembered that policies and practices utilized to successfully manage through fiscal challenge are not necessarily equally productive during fiscal growth. There are also several unique factors that the District must account for as it considers how to approach new resources. This includes declining or slow growth in enrollment, continued reliance on reserves to fully balance budgets, and notable fluctuations between budget and actuals. 7 Expenditure Analysis The District’s 2014-15 combined General Fund budget includes more than $95.3 million in expenditures, or approximately $8,860 per pupil. The salaries and benefits account for $82.3 million, or more than 86 percent of the budget. On a programmatic basis, the District’s 2014-15 budget for the special education program accounts for more than $22.3 million, or 23 percent of the budget, which is above the statewide average of approximately 20 percent. The 2014-15 adopted budget projects that more than $11.4 million will be contributed from the unrestricted General Fund to fully fund the special education program, which is a significant increase over the prior year’s contribution of $8.6 million. As of this review, the special education program budget (Resource 6500) appears to have approximately $1.2 million in unencumbered (i.e., potentially over-budgeted) salary and benefit expenses, materials and supplies, and contracted services budgets also appear to be over-budgeted. In most districts, special education programs can be challenging to budget for, but the level of unencumbered funds suggests that practices could be changed that would improve the accuracy of the budgeting process. In addition, changes in practices could allow for better communication about the impact of decisions on resource use within special education. A more in-depth analysis of the largest expenditure area, salary and benefits, was completed to address recommendations provided by the DBAC and to provide an assessment of how staffing and other allocation policies affect resource alignment. The salary and benefit analysis is completed for certificated and classified for the most recently completed fiscal year, 2013-14, plus two prior years to aid in identifying trends. On the natural, salary and benefit costs grow year-over-year as a result of longevity (i.e., length of service, step increases, and salary schedule improvements). However, the period of funding decline resulted in disruptions to normal trends as districts around the state reduced the quantity of staff and also, in many cases, sought concessions to reduce overall compensation. Figure 2 below provides an overview of certificated and classified salary and benefits from 2011-12 to 2014-15. The amounts for 2011-12 through 2013-14 reflect unaudited actual, whereas 2014-15 is from the 2014-15 preliminary budget. It appears from the data that compensation drops in 201415, but this is because the 2013-14 expenditure amount includes an extraordinary payment based on a stipulated agreement between the District and its certificated collective bargaining unit. Figure 2: Unrestricted and Restricted General Fund Compensation, 2011-12 through 2014-15 (dollars in millions) Year 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 2014-15 (est.) Certificated Classified Benefits Total Compensation $41.3 $41.2 $47.2 $42.4 $17.0 $17.8 $18.4 $18.5 $21.3 $21.2 $21.7 $21.5 $79.6 $80.2 $87.3 $82.4 Source: District Adopted Budgets, 2011-12 through 2014-15 As shown in Figure 2, there was negligible change in compensation expenditures from 2011-12 to 2012-13, with noted recovery and increases in 2013-14. While increases to compensation were 8 provided, a significant amount of the increase is accounted for in growth restoration of positions, both classified and certificated. During this period there were also shifts in the amount of unrestricted and restricted (i.e., categorical) funded positions. It is important to note that the implementation of the LCFF in 2013-14 has impacted how districts in California receive funding (most state categorical programs were eliminated and the majority of state funds are unrestricted). Notwithstanding the extraordinary payment made in 2013-14, expenditures for certificated staff have followed expected patterns for natural salary and benefit cost growth. By comparison, there were notable increases in the overall amount spent on classified staff, especially within the unrestricted General Fund. Figure 3 shows by types of classified staff the change in expenditures from 2011-12 to 2013-14. Figure 3: Unrestricted General Fund Classified Employee Salary Expenditures 2011-12 through 2013-14 Year 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 Classified Instructional Salaries Classified Support Salaries $116,251 $128,846 $245,497 $2,461,173 $2,973,089 $4,260,875 Classified Supervisor and Administrator Salaries $772,318 $1,018,734 $1,114,231 Clerical, Other Total Technical, Classified and Office Salaries Staff Salaries $3,013,189 $507,064 $6,869,995 $3,340,779 $781,147 $8,242,595 $3,899,017 $1,014,666 $10,534,286 Source: District Budget Sources Some expenditure categories such as classified instructional salaries and other classified have more than doubled during this time period. While there was a significant increase in classified support salaries, the increase is largely explained by shifting classified salaries that were previously charged to restricted resources such as economic impact aid and home to school transportation to the unrestricted General Fund. Similar analysis was performed on the employee benefit expenditures and the year-over-year increase from 2011-12 to the present. The changes appear to be reasonable for most of the categories, and the District’s higher rate of expenditures for employee benefits appears to be an historical trend. Keeping in mind the shift to LCFF in 2013-14, some of the increase is also likely due to shifting restricted General Fund expenditures resources to the unrestricted General Fund. It is important to note that while it appears that expenditures for the Public Employees Retirement System (PERS) have experienced increases this is balanced by the reduction/elimination of the expenditure for PERS Reduction. The rate of expenditures for other benefits has decreased and could be attributed to changes in retirement incentive payments. Our review notes that the classified and certificated collective bargaining agreements include language that provides for retiree health benefits. While there are some variations between the two agreements, retirement benefits can start as early as 55 years of age and continue on to age 65 or Medicare eligibility age (whichever comes first) and contain provisions to cover a percentage of cost increases. According to a 2012 survey by the California State Teacher 9 Retirement System, approximately 69 percent of employers provided some form of insurance premium support to retirees that are not yet eligible for Medicare.2 While not an uncommon practice, it can represent a considerable cost to districts to provide this type of benefit, which is often not considered when evaluating comparability in compensation between districts. Additionally, the rate of expenditures for worker’s compensation appears to be higher than expected, but this could be due to the manner in which the District secures its insurance (i.e., self insurance; relation to a higher than average rate of workers compensation claims or settlements). Comparisons to Other Districts The DBAC recommended comparisons in expenditure analysis with other districts with similar student demographics. Statewide data that compares expenditures is available through the 201213 school year. While this does not reflect recent increases, it does provide a basis for comparison as it can be assumed that given the demographic similarities between districts that they have seen comparable growth in funding since 2012-13. As noted earlier, compensation expenses account for the largest share of a district’s expenditures. As shown in Figure 4A and 4B, when compared to others in the comparison group, the District ranks the lowest among the comparison districts for certificated expenditures and the highest for classified salaries as a percentage of total expenditures. The District also ranks among the highest in terms of per pupil spending for certificated and classified salaries and benefits, which results in part from the addition of a period for all students grade 6 through 12 and provision of other post-employment retirement benefits. The District estimates that this results in an additional 22 full-time equivalent staff at an expense of $2.2 million. Figure 4A: General Fund Expenditures per ADA by Type of Expenditure (Salaries and Benefits), 2012-13 Cert. Salaries % of exp Classified Salaries % of exp Employee Benefits % of exp Los Banos Unified Woodland Joint Unified $3,501 47.7% $1,172 16.0% $1,772 24.1% $3,912 51.4% $1,342 17.7% $1,201 15.8% Lompoc Unified San Jacinto Unified Comparison District Average $3,964 $3,713 51.6% 48.0% $1,380 $1,143 18.0% 14. 8% $1,474 $1,506 19.2% 19.5% $3,997 48.2% $1,361 16.4% $1,651 19.9% Pittsburg Unified Kings Canyon Joint Unified $3,917 46.3% $1,225 14.5% $1,767 20.9% $4,065 47.5% $1,287 15.0% $1,736 20.3% Azusa Unified Monterey Peninsula Unified $4,531 51.1% $1,445 16.3% $1,499 16.9% $4,374 43.3% $1,896 18. 8% $2,255 22.3% District Name Source: EdData 2012-13 2CalSTRSEmployeeHealthBenefitStudy2012.Retrievedfrom http://www.calstrs.com/sites/main/files/file‐attachments/employer_health_benefits_study_2012.pdf 10 Figure 4B: General Fund Expenditures per ADA by Type of Expenditure (Books and Supplies, Services and Other Expenses), 2012-13 Books and Supplies % of exp Services and Other Expenses % of exp Total Expense* Los Banos Unified Woodland Joint Unified Lompoc Unified San Jacinto Unified Comparison District Average Pittsburg Unified Kings Canyon Joint Unified $341 $290 $257 $362 $267 $361 4.6% 3.8% 3.3% 4.7% 3.2% 4.3% $560 $859 $613 $1,011 $919 $1,195 7.6% 11.3% 8.0% 13.1% 11.1% 14.1% $7,346 $7,604 $7,687 $7,735 $8,296 $8,465 $550 6.4% $921 10.8% $8,559 Azusa Unified Monterey Peninsula Unified $293 $479 3.3% 4.7% $1,104 $1,091 12.4% 10.8% $8,873 $10,096 District Name Source: EdData 2012-13 As shown in Figures 5 and 6, teacher salary profiles based on information from the CDE’s 201213 J-90 (most current year available) reflect that the District’s lowest and average salaries for teachers are the lowest across the comparison districts, however, the District’s highest salary is ranked second among the comparison districts. Furthermore, when comparing salary profiles in Monterey County, the District ranks 11 out of 18 for both the lowest and average salary, and 9 out of 18 for the highest salary. It is important to note that the District’s salary schedules do not account for the additional compensation provided to middle school and high school teachers for the additional 8th period. Furthermore, as noted earlier the District provided post-employment retiree health benefits, which increase benefit costs, but do not appear on the salary comparisons. Figure 5: 2012-13 Teacher Salary-Comparison Districts District Total Salary Schedule FTE Lowest Salary Average Salary Highest Salary San Jacinto Unified Los Banos Unified Lompoc Unified Kings Canyon Unified Azusa Unified Pittsburg Unified Woodland Unified Monterey Peninsula Unified 358.50 405.00 428.68 451.55 471.72 504.90 507.41 530.17 $42,433 $38,907 $40,034 $38,672 $45,017 $41,429 $40,134 $38,200 $68,868 $63,331 $63,948 $63,621 $71,930 $60,839 $61,900 $57,950 $86,187 $82,033 $79,240 $82,268 $81,588 $76,884 $76,742 $84,034 Source California Department of Education 2012-13 J -90 11 Figure 6: 2012-13 Teacher Salary-Monterey County Districts* District Total Salary Schedule FTE Lowest Salary Average Salary Highest Salary Graves Elementary San Lucas Union Elementary Mission Union Elementary San Antonio Union Elementary Spreckles Union Elementary Washington Union Elementary South Monterey Joint Union High Gonzales Unified Pacific Grove Unified King City Union Elementary Greenfield Union Elementary Carmel Unified North Monterey Unified Soledad Unified Alisal Union School District Salinas City Elementary Monterey Peninsula Unified Salinas Union High 2.50 5.00 7.90 10.00 41.85 45.00 76.00 111.60 114.10 146.00 151.00 160.00 214.00 225.00 307.00 373.71 530.17 659.32 34,291 35,874 43,400 37,896 39,448 41,583 33,231 41,214 42,300 34,303 36,000 52,167 39,807 42,047 37,743 40,110 38,200 38,933 52,295 45,040 53,544 50,746 52,273 60,893 74,902 62,837 78,457 56,349 54,320 89,303 61,377 63,059 64,853 64,012 57,950 69,356 64,297 69,174 69,500 64,949 78,101 74,410 102,188 88,046 98,168 81,059 84,679 107,138 83,485 90,568 84,569 80,067 84,034 91,524 * Data excluded for non-reporting districts – Big Sur Unified, Bradley Union, Chualar Union, Lagunita, San Ardo Union, and Santa Rita Union. Source California Department of Education 2012-13 J -90 As noted earlier, the District’s expenditures for employee benefits is above most districts in the comparison group. There are many components to a district’s benefit expenses. Figure 7 shows a breakdown for the District and comparison group of the various benefit expenses by type. As shown, the District’s Post-Employment Benefits are a factor of two to three times that of most districts in the comparison group when compared based on amount per student. 12 Figure 7: 2012-13 Unrestricted General Fund Employee Benefit Expenditures Per ADA District State Teachers Retirement System Public Employees' Retirement System OASDI/ Medicare/ Alternative Health & Welfare Benefits State Unemployment Insurance Workers' Comp. Insurance $4 $74 $86 $267 $46 $56 $239 $80 $96 $75 $42 $226 $87 $98 $440 $263 $95 $111 San Jacinto Unified Azusa Unified $238 $116 $290 Kings Canyon Joint Unified Pittsburg Unified Monterey Peninsula Unified Woodland Joint Unified Los Banos Unified Comparison District Average Lompoc Unified PostEmployment Benefits PERS Reduction Other Benefits Total $42 $6 $33 $615 $41 $47 $5 $0 $624 $44 $102 $62 $7 $24 $477 $46 $57 $58 $8 $7 $88 $414 $44 $109 $55 $4 $66 $83 $103 $397 $45 $136 $30 $7 $47 $254 $76 $94 $663 $42 $73 $79 $7 $0 $253 $76 $94 $660 $47 $142 $45 $5 $0 $263 $94 $110 $566 $43 $199 $139 $13 $37 $1,0 89 $1,1 22 $1,1 36 $1,1 38 $1,2 88 $1,3 22 $1,4 65 Source ; EdData Practices to Support Alignment Budgeting has been part of education since the first public investments were made to educate students. Many people think of budgets as pages filled with numbers, and while they can take that form, a budget is much more than numbers. Good budgets begin with an understanding of needs and then show how the available resources can be deployed to address identified needs. Budgets developed with this approach can tell the story of how all available resources support desired student outcomes. The implementation of LCFF calls for local education agencies to make a mindset shift when creating their budgets. Budgets need to migrate from the past practice of largely reflecting inputs, reinforced by how the state provided funding, to a performance-based approach reflecting outcomes and outputs. Figure 8 provides an overview of many of the major shifts underway throughout California as districts move from focusing on compliance requirements to being performance focused. 13 Figure 8: Overview of Performance Focused Shifts Responsibility for the Plan Stakeholder Involvement Approach to the Money Time Measure of success/results Orientation Scope and Approach COMPLIANCE Lowest level staff write and complete the Plan Invite and inform required stakeholders Submit a rollover budget Episodic, aligned to required timelines Compliant plan, signed off by the approving entity Equity Communication Extra work Components/silos (program, resource, req. office) Equal funding Rules and regulations Data NCLB disaggregation PERFORMANCE Leadership function with Superintendent buy-In Seek critical stakeholder input (know who needs to be involved) Resources are aligned to goals Ongoing, continuous improvement cycle Plan implemented that positively impacts student outcomes Is the work System Equal outcomes Capacity development (basic understanding of the relationship to the whole) Deeper analysis that is locally meaningful Source: WestEd Under LCFF, student needs should drive spending decisions rather than grant requirements and specific programs. While local educational agencies are expected to meet various state priorities associated with LCFF, it is up to each district to specify how they will meet these metrics, what measurements they will use, and how resources will be allocated to support goals, actions, and services. In other words, the shift in state policy under LCFF is very compatible with the District’s objective to make improvement in how it aligns resources. The District’s LCAP has five overarching goals that are based on identified student needs. The goals include: All students, including all subgroups, will make academic progress in the core academic areas of Mathematics, English/Language Arts, Science, Social Science, and Visual and Performing Arts. Monterey Peninsula Unified School District (MPUSD) students will meet or exceed state averages when state Smarter Balanced test scores are available in 2015. All students and all subgroups will engage their individual learning styles and interests to acquire 21st century skills and passion for continuous learning as they pursue higher education or career technical pathways, technological infrastructure and support will be developed to meet the needs of students. By year three of LCAP all teachers in MPUSD will meet the federal standard for highly qualified teachers (HQT), and opportunities for high quality professional development. 14 MPUSD will recruit and retain HQT teachers. All students, including all subgroups, will have equal access to a broad course of study, including but not limited to Advanced Placement classes, visual and performing arts, and Common Core aligned core academic instruction. All students, including all subgroups, will be provided a safe and healthy environment to achieve social, emotional, academic success. The District’s LCAP also contains a variety of actions, services, and resources as well as expected outcomes to support the goals identified above. A critical step in the implementation of LCFF is the Annual Update. Each year the District will complete an Annual Update and will measure the progress toward expected outcomes against actual outcomes and perform an assessment of effectiveness of specific actions and services. Based on this information, the District will determine if any changes in goals, actions, or services or allocation of resources are needed to achieve expected outcomes. The District has included a curriculum audit as an action to support Goal 4 of its LCAP for 201415. This information will be a valuable resource as the District works on its Annual Update to determine if programs, actions, and services are aligned to needs and goals and services/actions are creating improved opportunities, outcomes, and outputs for all students. If it is determined that changes are needed, it will be critical to identify and prioritize new/different/improved actions or services that will be responsive to achieving the goals. When prioritizing actions and services, questions that are helpful to the process include, “Will implementing this activity directly address improving student outcomes? Does this activity address the most critical needs of our students or which group of students will this activity impact?” After new actions/services have been determined, the budget will need to be adjusted to provide allocations to support the changes. The District has a longstanding practice of allocating resources to its school sites. As the District works to align resources, it should not only revisit the underlying formulas to make allocations, but also refine guidance and support for sites to maximize the use of resources. Following is background and analysis that may help the District assess its existing allocation practices. Site and Federal Funding Allocations There are two parts to any school district budget. The unrestricted General Fund comprises nearly 85 percent of the District’s General Fund. Most of this revenue goes towards paying operational costs, including teacher and administrator salaries. The other type of funding is restricted, or categorical funding. This includes federal programs, such as Title I, Title II, and Migrant Education. Since the implementation of LCFF, there are just a handful of state categorical programs left such as special education and restricted lottery. The District shared that there are several restricted funding sources that they no longer receive such as California Clean Energy Job Act and Federal Character Education, and it appears that the revenue and expenditure budgets reflect the discontinuation of funding. Additionally, District 15 documentation for restricted resources reflects that there were no carryover funds for Economic Impact Aid at the close of the 2013-14 fiscal year. Title I Title I, Part A, was initially funded in 1965 as part of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA). Over the years, ESEA has been reauthorized by Congress, most recently as the 2001 No Child Left Behind Act. The purpose of Title I is to provide additional support to supplemental core or base educational programs targeted at low-income and low-performing pupils. The amount of Title I funds provided to local educational agencies (LEA) is determined based on the numbers of low-income pupils in the area of residence of the LEA. In recent years, the amount of Title I funding provided to LEAs can vary from year to year due to reductions in funding for the program by Congress, increases in state and local set asides for charter schools and other designated purposes, and fluctuations in counts of low-income pupils. There are several areas to consider when optimizing Title I funds. Eligibility—The process and selection of schools to provide funding to based on meeting ranking and selection criteria Distribution—The amount of funds allocated to district-directed initiatives and school site discretion Uses—The manner in which funds are used against fiscal management standards Eligibility Any school that is at or above the districtwide rate of poverty and/or exceeds 35 percent poverty is eligible to receive Title I funding. An LEA may determine “poverty” levels based on a variety of data, but the most commonly used data are free and reduced-priced meal counts. Generally, each LEA lists schools, in rank order (high to low), by the percent of students enrolled who are deemed low-income based on student eligibility for free and reduced-priced meals. Based on this ranking, schools are selected for funding. It is not necessary that all schools that are above the districtwide average poverty level or 35 percent poverty be provided with Title I funding, but it is necessary that schools with higher poverty rates be funded before those with relatively lower poverty rates. There are a few areas of discretion allowed for LEAs when making selection decisions including: Alternative Data—In addition to free and reduced-priced meal eligibility data, other data that may be used for rankings includes Census data, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) eligibility, Medicaid eligibility, or some composite of these data sources. Rankings Districtwide or Grade Span—Any school above 75% poverty must receive first priority for funding, but once such schools are funded, LEAs may decide to rank based on districtwide listing of schools or grade span. If grade span is selected, it is possible to include a subset of schools (e.g., elementary only and no high schools). 16 Skipping—An otherwise eligible school may be skipped if the district can demonstrate that a comparable amount of state or local funds provided in lieu of Title I (e.g., Quality Education Investment Act (QEIA) funding for selected school sites could be argued to meet this criteria, or alternative education programs that receive Pupil Retention and Community Day School support). Feeder School Data—Poverty data from feeder schools may be used to calculate the poverty rate of a high school. The purpose of this option is to offset underreporting of free and reduced priced meal eligibility that tends to occur at high schools because students prefer to remain unidentified. Grandfathering—If a school drops out of eligibility for a one year period based on its poverty counts, it may continue to receive funding. Of the District’s 20 schools in 2013-14, ten were considered eligible based on the District’s criteria to receive Title I funds. However, 12 schools did not receive funding in 2013-14 because among the potentially eligible schools, two were skipped because they were provided other state or local funds. Distribution Title I laws and regulations call for each LEA to determine how to allocate funding to meet required set-asides, district administrative requirements, district-directed needs/initiatives, and site level support. The distribution of Title I funds may only be to Title I-eligible sites and generally targeted to Title I-eligible students3. There are a number of required and optional setasides that are to be made from Title I funds “off the top,” or before determining the amount allocated to eligible school sites. The following depicts these set-asides. 3 Title I-eligible students include any student who is low-income or low-performing. By default, when a school receives Title I funds, it is considered for uses that are “Targeted Assistance,” which means limited to compensatory support for eligible students alone. Any school with at least 40 percent of its student population eligible based on poverty data may elect to be a “schoolwide” Title I school provided that the local site council elects to be in schoolwide status and CDE is notified through the Consolidated Application process. Schoolwide schools receive the flexibility to direct Title I resources to the schoolwide strategies that may benefit any student, provided the use offers supplemental support. 17 Category Administration, including indirect costs Highly qualified teachers Professional development, for school or LEA in program improvement Supplemental education services, LEAs with one or more schools in program improvement Parent involvement Homeless Teacher incentives Set-Aside 15% 5% 10% Up to 20% At least 1% LEAs need to reserve the amount equal or comparable to those provided to Title I schools for (1) homeless children who do not attend Title I schools and (2) children in local institutions for neglected children Up to 5% In addition to the set-asides listed above, LEAs are permitted to direct Title I resources to centralized services, such as preschool, summer school, school improvement, and coordinated services. Funds may also be reserved for district-directed services, provided that the activities are allowed under Title I. In other words, services are supplemental, address the needs of Title Ieligible students and are aligned to goals and services included in the LCAP. LEAs should ensure that such uses are identified within the LEA’s Local Education Agency Plan (LEAP) and school site Single Plans for Student Achievement (SPSA). Additionally, LEAs should consider including Title I resource information in their LCAPs to provide transparency on the continuum of services and actions for students. Funds that that remain after allocation for set-asides are for site direction and inclusion in SPSAs to all eligible schools. There are several specific rules that may apply when determining the sitelevel allocations that include priority for high poverty schools, concentrated funding for high poverty schools, differential amounts and inclusion of private schools. The District’s allocation formula includes set-asides for supplemental educational services, parent involvement, homeless, and administration are taken before all other allocations are made. Once the set-asides are made, the District divides remaining funds by a formula that provides a set amount per low-income student per eligible site. Carryover funds are retained by each site up to District defined threshold, after which the carryover is centralized. Uses The District’s documentation regarding its allocation plan indicates that there are centralized services included within the allocation plan and it appears that the services are likely direct services. Site expenditure documentation reflects that expenditures are heavily weighted towards employee compensation. There is little differentiation between site expenditure patterns; the majority of sites appear to have both teacher and a combination of classified support. 18 Carryover No more than 15 percent of Title I funds may be carried over in any given grant award period. The calculation of carryover is based on expenditures at the end of June 30 of the fiscal year, but also may be counted through September 30 if by June 30 the 15 percent limit is exceeded. Since most LEAs allocate the vast majority of Title I funds to sites, often when there are issues with carryover, they are due to site administrators not fully understanding the rules and requirements related to Title I. Based on data provided by the District, carryover balances for 2013-14 for the majority of the sites were under well under the 15 percent limit, however, there were two sites that had carryover balances of more than 40 percent of their allocation. The District’s overall carryover appears to be within the 15 percent limit when considering the September 30 cutoff. Title II and Title III The purpose of Title II, Part A is to increase the academic achievement of all students by helping schools and LEAs ensure that all teachers are highly qualified as well as improve teacher and principal quality through professional development. This resource can also be used to reduce class sizes. District documentation reflects that there is a significant investment in certificated administrators and other certificated employees with approximately 63 percent of 2013-14 expenditures directed towards these categories. The purpose of Title III is to support English language learner students acquire English and achieve grade-level and graduation standards. This resource can be used to support a number of services and actions such as English language development instruction, high quality professional development, community participation in programs, and coordinating language instruction programs with other programs, e.g. Title I and Migrant Education. District documentation reflects that this resource is not as heavily invested in staff, however, there appear to be a trend of adopting budgets that are not reflective of actual expenditures. For instance, in both 2012-13 and 2013-14 when the budget was adopted, there was a significant amount of funds budgeted for professional services which were subsequently re-allocated to other budget categories throughout the year, which maybe an indication that there isn’t an aligned plan in place. While there are no carryover limitations for Title II or Title III, funds need to be expended within the grant award period. There are fluctuations in carryover amounts for both resources on a yearover-year basis that are related to planned expenditures, which do not materialize as planned initially. Summary of Findings The District has a history of deficit spending in the unrestricted General Fund and the current budget and multi-year projection reflect that this trend will continue, but there appears to be an opportunity to reduce the projected deficit by revising special education expenditure budgets. Additionally, there is a projected deficit for the restricted General Fund deficit that appears to be related to expending carryover balances for Common Core State Standards and mental health services. 19 The District’s budget assumptions for 2014-15 appear to be reasonable, but there is a history of the ending fund balance increasing between what is estimated at budget adoption and what the actual amount is when the District’s fiscal year is closed in September. Compensation is the largest area of District expense. While the District is generally comparable to other Districts, there are some differences in the amount and level it spends on classified salaries and employee benefits. The District ranks within the comparison group as spending among the lowest percentage of its budget on certificated salaries, but spends more per student on certificated salaries than other districts in the comparison group. Also the District’s teacher salary profiles is lower than expected when compared to districts in the comparison group. This suggests that the District may not be as successful retaining staff and/or that the District tends to have larger class sizes. o Specific comparison points (lowest and average salary) on the teacher salary profiles are amongst the lowest in the comparison group and when compared to districts in Monterey County, the District’s lowest, average, and highest teacher salaries for 2012-13 ranks in the middle of the group. o Multi-year analysis reflects that there have been significant increases in classified support, classified administrator, and other classified expenditures that are likely due to additional positions being added in recent years. o Multi-year analysis for benefit expenditures reflects that the higher than average expenditures for other post retirement benefits and worker’s compensation is a historical trend. The District’s collective bargaining agreements for classified and certificated employee groups contain language for retirement benefits which present a challenge in allocating resources to fund the future liability for other post retirement employee benefits. The District has a budget development system in place, but it appears that financial performance rather than student performance has been the primary driver. While there cannot be a diminished focus on the importance of accurate revenue forecasts, historical trends, and patterns, LCFF presents both the opportunity and an imperative to use performance-based budgeting to better align all resources to support improvement in student outcomes. The District’s 2014-15 LCAP reflects that a significant investment of supplemental and concentration funds (25 percent) will be allocated to sites to serve the unique needs of students. The District has the opportunity and responsibility to build capacity among its site level leadership to better align site level resources to support improving student outcomes. Recommendations and Options to Consider 1) Develop a clear vision for instruction within Monterey Peninsula Unified School District to add depth to existing goals and actions. This District has begun a comprehensive analysis and planning process with studies and reviews of the District’s curriculum, facilities, and 20 finances. There are also relatively recent Board goals and a process for updating such goals. For the District to support resource alignment, a clear vision for instruction must be present around which goals, initiatives, and actions can be aligned. As this begins to emerge, deliberate attention should be given to instituting management practices that reinforce resource alignment. Following are several examples of promising practices: a) With the vision for instruction in mind, clearly identify objectives for sites and a multi-year plan to shift and/or clarify site allocation and planning practices. There should be processes recommended or mandated that support sites in effective planning for school site needs that align to District priorities with routine progress monitoring and support for outcomes. Such a plan should also provide sites with a clear understanding of how budgets will grow and be related to needs and outcomes. b) Improve budget transparency and communication. The District budget documentation is inherently complex and lacks clear explanation of how resources connect to District goals. The District should work to develop the budget to explain how resources are related to goals. The LCAP currently requires a reporting of resources for each specific action/service. A summary showing a resource summary with emphasis on alignment towards outcomes would reinforce for stakeholders the value and importance of resource alignment. c) Create a data display or dashboard that includes key indicators for routine progress monitoring of District goals and priorities with resources noted. This will aid in communication and transparency, as well as ongoing planning and attention to the importance and value of resources. d) Revisit site allocation to balance site-specific autonomy to address needs with District identified vision. Current allocation practices reflect historical precedent and in some cases lack a clear rationale. As the District clarifies its vision, it should consider how to engage sites in needs assessment, planning, and accountability as a means to develop a performance focused culture. This could include initiating changes with specific funds (e.g., Title I, LCFF) as a means to pilot before scaling districtwide. 2) Use regular Executive Cabinet meetings and time with site administrators to improve resource planning, adherence with budget procedures, and progress monitoring. The District has lacked strong connections between curriculum planning and budget management. The process for developing more robust systems to support resource alignment require intensive teaming between the various District departments (e.g., Educational Services, Human Resources, Fiscal) and the District with sites. The District may want to consider creating a standing resource alignment item for its strategically oriented cabinet and site meetings with a clear agenda for the year as to how this strand of dialogue will contribute to evidence of improved practice. Areas of focus/attention could include: instructional priorities and expectations for resource alignment, fiscal management practices, progress monitoring metrics including resource considerations, needs analysis and relationship to allocations, and stakeholder communication regarding resources and impact on students. 3) Revise or eliminate the eight period day. The District’s curriculum audit identified concerns regarding the effectiveness of the eight period day, which merit consideration. The District 21 should consider the cost-effectiveness of this approach as it assesses how it aligns resources to strategic priorities. 4) Complete a more in-depth study of the special education program to identify practices that contribute to unpredictable costs, overall costs of the program, and impair or contribute to program quality. The overall costs of the District’s special education program are above that of statewide averages. There have also been significant increases and variances within the program’s budget. Areas to consider include individualized education program (IEP) development process with attention to criteria for goal setting and service provision, staffing approach and alignment to student needs, organizational structure, and relationships with parents and quality of communication. 5) Improvement alignment of classified staff to District priorities and needs. As the District increases its investments in positions it should carefully current classified staffing levels and structures to ensure that existing and new positions are in alignment with the District’s strategic objectives. 6) Transition the work of the District Budget Advisory Committee to supporting LCFF and LCAP planning. The DBAC should be viewed as one of the groups consulted in the budget and plan development process. The DBAC can complement other voices in this process such as the parent advisory group, English learner advisory group, site councils, and staff and students. Potential areas of focus for the DBAC could include informing district prioritization and being an outreach to others to support communication about the budget as a resource to achieve District goals for students. 22

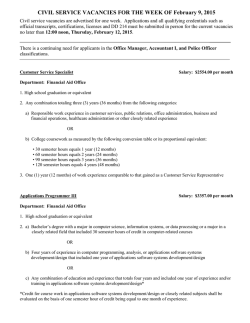

© Copyright 2026