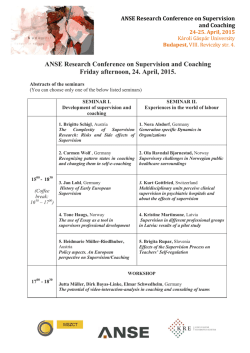

ANSE Research Conference on Supervision and Coaching

ANSE Research Conference on Supervision and Coaching 24-25. April, 2015 Károli Gáspár University Budapest, VIII. Reviczky str. 4. ANSE Research Conference on Supervision and Coaching Saturday, 25. April, 2015. Abstracts of the seminars (You can choose only one of the below listed seminars) 1000 - 1130 PhD and master thesis platform Possibility, depending on interested participants SEMINAR III. Relations between research and practice 1. Hansjörg Künzli, Switzerland 1000 – 1400 SEMINAR IV. Diverse approaches to Supervision research 1. Yasmin Aksu, Germany Using the micro-level perspective of conversation analysis to improve communication in supervision 2. Silja Kotte, Germany 2. Frank Austermann, Germany Research and Practice in Coaching Do acceleration and boundless work lead to an and Supervision: How to Build on an accelerated and boundless coaching? Ambivalent Relationship? (Coffee break: 30 11 – 1200) 3. Anja Appel, Austria Supervision and Coaching in NonGovermental Development Organizations 4. Katrin Oellerich, Germany Negative effects of coaching and their causes from the perspective of organizations 3. Eva Graf, Austria Process research on coaching – what the linguistic perspective has to offer 4. Denise Schubert, Germany Why do coaches (not) participate in coaching research? 5. Volker J. Walpuski, Germany ‘Always on’ - Dealing with a Constant Availability ANSE Research Conference on Supervision and Coaching 24-25. April, 2015 Károli Gáspár University Budapest, VIII. Reviczky str. 4. Abstracts of the seminars on Saturday, 24. April 2015 SEMINAR III. Relations between research and practice 1. Hansjörg Künzli, Switzerland 2. Silja Kotte, Germany - Research and Practice in Coaching and Supervision: How to Build on an Ambivalent Relationship? Although both researchers and practitioners in coaching and supervision stress their mutual importance, they nevertheless often look at each other skeptically. Practitioners criticize that research often neither inspires nor informs nor instructs their practice (Padberg, 2012; Möller, Kotte & Oellerich, 2013). Researchers on the other hand shake their head in disbelief at what is being sold (and bought) especially in the field of coaching without empirical evidence (Kieser, 2005) and lament practitioners’ unwillingness to contribute to research. In my talk I argue that in order to move towards a more fruitful working alliance between research and practice in coaching and supervision, we need to take seriously the inner logic of each of the two fields and then look for practical and creative ways of cooperation. The difference in primary tasks of the two fields of research and practice – generating knowledge vs. enabling clients to better understand and deal with their situation – leads to conflicting approaches in dealing with (i) complexity, (ii) the intimacy of the counselling process, and (iii) mechanisms of knowledge generation. Coaching/supervision ultimately aims at reducing complexity in order to enable clients to make informed choices and act on them, whereas research rather increases complexity: “organized skepticism” (Kieser, 2005) is at the heart of the scientific approach of further differentiating and questioning the present state of knowledge. The intimacy of the working alliance is central to coaching and supervision. It is considered one of the most relevant process factors contributing to coaching success (De Haan, et al., 2013; Ely et al., 2010; Grant, 2013). Research needs to interfere in the intimacy to derive valid conclusions beyond mere posthocsurveys. Knowledge in the community of practice is generated from the experiences of coaches and supervisors and the curricula of training institutions, and is passed on primarily within a “matrix of masterapprenticerelationships” (Haubl, 2009). The knowledge such generated is implicit and case-specific. Knowledge in the scientific community, in contrast, is generated through a re-iterated process from singular scientific initiatives through peer-criticism to methodological and epistemological controversies. As “dwarfs on the shoulders of giants”, researchers further refine the explicit, general stock of knowledge that has been built up by previous generations of researchers. In spite of these fundamental differences between research and practice in coaching and supervision, both sides depend on each other. Coaches and supervisors will be required more and more both from clients and from professional associations to demonstrate evidence and engage in quality assurance. ANSE Research Conference on Supervision and Coaching 24-25. April, 2015 Károli Gáspár University Budapest, VIII. Reviczky str. 4. Researchers need sufficiently large samples of coaches/supervisors and their clients to do research on. They hence both need to win each other over for actual cooperation by generating benefit for the other. How? Researchers need to see themselves also as service providers for practitioners. This includes: systematically surveying practitioners’ needs, expectations, and attitudes towards research, developing empirically sound yet practical evaluation tools as well as making the academic stock of knowledge accessible to practitioners. Practitioners need to open their coaching/supervision processes to researchers: they are challenged to question themselves whether protecting clients’ intimacy might have served as a convenient argument to avoid their own fear of being observed by a third party. And they are called to conform to guidelines provided by researchers, for example on case study description, so that their practical experience can be incorporated in the stock of knowledge on coaching and supervision. Author: Silja Kotte, Dipl.-Psych. (M.Sc. Psychology), Supervisorin DGSv Kassel University, Department of Psychology, Chair of Counselling Theory and Methodology Holländische Straße 36-38, 34127 Kassel Phone +49 (0) 173 45 37 920 E-mail:[email protected] ANSE Research Conference on Supervision and Coaching 24-25. April, 2015 Károli Gáspár University Budapest, VIII. Reviczky str. 4. 3. Anja Appel, Austria - Supervision and Coaching in Non-Govermental Development Organizations Background In the Third Sector (also known as Non-profit sector), especially in organizations which deliver social or welfare services, supervision and coaching are established instruments of human resource management and of quality assurance. They are already institutionalized in the training cycle and produce recognized costs for professional development. But in another subcategory of the Third Sector, the Non-governmental Development Organizations (NGDOs), a totally different approach to counseling formats as supervision and coaching, can be observed. While the term “NPOs” typically refers to “nonprofit” or “not-for-profit” organizations working in the state welfare and social sector and frequently offer services, NGOs refer to international political and advocacy organizations, mainly in the environmental and international development sector. Increasing contradictions between expectations of and structural challenges for NGDOs have long been visible. While the professionals face a huge number of challenges in the policy field, counseling formats are more or less rarely used. Aims of the presentation The presentation portrays the political field of development politics as well as its structural characteristics. Using a multilayer model, it shows the position of non-government development organizations (NGDOs) and the challenges in organizational theory and practice associated with it. Moreover, topics and occasions which seem appropriate for supervision, coaching or organizational consulting will be identified. A comparison between the analysis and the results of expert interviews will illustrate the discrepancy between what is theoretically useful for a consulting process and what is put into practice. (Dr. Anja Appel is a political scientist and member of ÖVS – Austrian Society for Supervision.) ANSE Research Conference on Supervision and Coaching 24-25. April, 2015 Károli Gáspár University Budapest, VIII. Reviczky str. 4. 4. Katrin Oellerich, Germany - Negative effects of coaching and their causes from the perspective of organizations Coaching is booming – the request and the implementation of coaching in business contexts as an instrument of leadership and employee development is increasing continuously (Ely et al., 2010). Organisations are investing high sums for the realisation of coachings (e.g. 330 Million €/Year in Germany, source: DBVC, 2012). Even though research on the efficacy of coaching and its active factors leading to efficacy, is a very new and heterogeneous field, it is legitimate to say that coaching is effective and can lead to very positive results for the clients (Grant, 2013; De Haan, 2013; Ely et al., 2010). It seems unlikely that something that has such strong effects does not have negative outcomes for clients and other members of organisations and it is absolutely necessary to explore the ‘dark side’ of this popular and important instrument. The very few existing studies in this field, investigating the perspective of clients and coaches, show that diverse negative effects can occur for the clients (for example the client becomes ‘dependent’ on the coach and is unable to make decisions on his/her own; Schermuly et al., 2014; Seiger & Künzli, 2011). The perspective of members of organisations who are ‘outside’ the coaching process has not been explored yet, even though business coaching is - by definition – located in business contexts. Another step is to explore the causes for these effects: Where do they come from? What exactly are the causes? The causes – or the risks – that affect the efficacy can emanate from the client, the coach, the quality of their working alliance, the coaching process or organisational factors (for example the coach does not have enough professional expertise for the ‘case’; the client has false expectations concerning the coaching; Schermuly et al. 2014). In this study subjective ratings on negative effects and their causes are being explored from the view of managers whose subordinates have been coached and HR-specialists, who arrange coachings. In a qualitative pilot study, interviews are being conducted with five members of each group. The results of the explorative pilot study will be the base for the development and validation of a questionnaire and a quantitative survey (N=50/50). First findings from the qualitative study show that positive outcomes of coaching for the client can be negative for others. For example if the client learns in coaching how to better win recognition when dealing with his/her manager, the new attitude of the client/subordinate can be very uncomfortable for the manager (conflicts occur, that have not been existent before). Until the time of the conference the qualitative content analysis will be completed and the preliminary findings substantiated. (Contact: Frau Katrin Oellerich [email protected] Universität Kassel, Institut für Psychologie Holländische Straße 36-38., 34127 Kassel, Tel. +49 (0) 561 804 2977) ANSE Research Conference on Supervision and Coaching 24-25. April, 2015 Károli Gáspár University Budapest, VIII. Reviczky str. 4. SEMINAR IV. Diverse approaches to Supervision research 1. Yasmin Aksu, Germany - Using the micro-level perspective of conversation analysis to improve communication in supervision 2. Frank Austermann, Germany - Do acceleration and boundless work lead to an accelerated and boundless coaching? ANSE Research Conference on Supervision and Coaching 24-25. April, 2015 Károli Gáspár University Budapest, VIII. Reviczky str. 4. 3. Eva Graf, Austria - Process research on coaching - what the linguistic perspective has to offer While outcome research on coaching is by now more or less well established, the interest of researchers has lately turned to questions regarding the coaching process itself, i.e. the concrete interaction between coach and client during a coaching session and/or a coaching process (see e.g. Wegener in prep.). According to de Haan et al. (2010: 110): In order to understand the impact and contribution of executive coaching and other organisational consulting interventions, it is not enough to just understand general effectiveness or outcome. One also has to inquire into and create an understanding of the underlying coaching processes themselves, form the perspective of both clients and coaches. To put it differently, it is not sufficient for the quality discussion and professionalization of coaching to know THAT coaching works, we need to inquire into HOW coaching works. I.e. we need to get a feeling for what happens in the black box ‘coaching’, for how established success criteria such as “the coaching relationship” are interactively and linguistically co-constructed by coach and client alongside their conversation. To contribute to our understanding of coaching – both as researchers and practitioners – process research needs to focus on whole coaching sessions or whole processes and needs to include both, coach and client, alike (Bachkirova et al. 2011). Furthermore, given that coaching is (nothing but) a particular professional helping conversation (De Haan et al. 2010; Sator/Graf in press; Graf/Pawelczyk in press), it needs a detailed analysis of the locally emerging conversation between coach and client. Such a micro-analytic perspective on (coaching) conversations is offered by the integrative discourse analytic approach to coaching (Graf in prep.; Graf in press), which entails the following: qualitative approach authentic coaching data, linguistically transcribed interpretation of data based on participants’ (i.e. coach and client’s) own interpretation of the situation (‘display rule’, Sacks, Schegloff & Jefferson 1974) focus on whole session AND all participants, i.e. coach and client The linguistics contribution to coaching process research adds the following to our understanding of the coaching interaction itself: coaching consists of four basic activities, ‘defining the situation’, ‘establishing the relationship’, ‘co-constructing change’ and ‘evaluating the coaching’ (Graf in prep.), that help – as an analytic inventory or metalanguage – to explain both the interactive particularities of a whole coaching process and of individual sessions. Especially with regard to future coach training programs, to better understand how exactly ‘contact’, ‘relationship’ etc. are locally and interactively established in and through the particular conversation between coach and client is highly relevant and a so far missing information. Furthermore, discourse analytic findings “can make evident practices of which therapists [and coaches; EG] are not explicitly aware” (Leudar et al. 2006: 28)” . Concrete examples from the activity ‘defining the situation’ will serve as illustration. ANSE Research Conference on Supervision and Coaching 24-25. April, 2015 Károli Gáspár University Budapest, VIII. Reviczky str. 4. 4. Denise Schubert, Germany – Why do coaches (not) participate in coaching research? The literature on coaching has grown exponentially in the last few years. While coaching is often considered as a useful tool for individual and organizational development (Grant, Passmore, Cavanagh, & Parker, 2010), empirical studies generally lack a firm theoretical foundation (Grant, 2013; Möller & Kotte, 2011; Ely et al., 2010). Moreover, ecologically valid studies need to be based on sufficiently large samples of coaching practitioners. Therefore high quality coaching research depends significantly on practitioners` willingness to participate. The purpose of the present study is to explore coaches’ reasons for participating – or not – in coaching research. Results should help to identify attitudes and motivations that affect coaches` willingness to participate. The findings could then be taken into consideration in planning and conducting future research projects. The sample consisted of 50 coaches who filled out an online survey (response rate 58%). The survey used for this study was a revised version of the Attitudes to Psychotherapy-Research Questionnaire (APRQ) (Taubner, Munder & Klasen, in prep.). It includes six scales: legitimation of coaching as a counseling format through research, belief in the effectiveness of coaching, expected increase in knowledge about and quality of coaching through research, effort required for research, expected harm for and interference with the coaching process through research as well as self-doubt as coach including the coaches’ fears of being judged by an external party. Additional qualitative questions refer to exclusion criteria (“What would prevent you from taking part in coaching research?”) and preconditions for participation. Mean values for the whole sample showed highest scores for legitimation, followed by effectiveness belief and increase in knowledge and quality. Coaches appear to feel highly confident in the effectiveness of coaching. They expect that research will legitimize their practice as well as help to improve the quality of coaching as a whole and of their own professional practice in particular. Results from the qualitative analysis revealed the importance of an adequate balance between effort and benefit for the coaches. Moreover, they highlighted the particular importance of the relationship between coaching practitioner and researcher. In addition, the interruptions and disturbances coaches anticipate to their coaching processes were also specified. A preliminary multiple regression showed that the scale increase in knowledge and quality predicts the coaches` willingness to participate in research. Increasing the sample size until the time of the conference is expected to consolidate these preliminary findings. (Denise Schubert & Heidi Möller - Universität Kassel) ANSE Research Conference on Supervision and Coaching 24-25. April, 2015 Károli Gáspár University Budapest, VIII. Reviczky str. 4. 5. Volker J. Walpuski, Germany - ‘Always on’ - Dealing with a Constant Availability Mobile communication devices like smart phones are keystones for improving efficiency, compacting and subjectifying work. They spread very quickly and are ubiquitous meanwhile. They dissolve boundaries not alone between work time, obligation time, and leisure time, but also between places, and real life/virtuality in multiple ways. Three dimensions should be focussed: a) Mobile communication is influencing the individual. Devices often are used without reflection or with an ambivalent connotation with positive tendencies. But these devices force individuals to make microdecisions permanently. A self-endangerment due to various reasons (e. g. career, personal advantages, job- or livelihood security) pressurizes the individual to be ‘always on’. At a glance, mobile communication offers many advantages. A profound look shows the psychological strain connected to it. The referring keywords are conformity, gratification, and anxiety. The usual way to cope with these problems is to subjectify them: The individual should solve them. Supervision and coaching can help to reflect self-organisation and self-endangerment, norms within a group and the use of technical devices in general. Supervision works as a decelerator and interrupter of a ‘24/7 here-and-now‘ imposed on us by mobile communication. It is a kind of dead spot inspiring to reflect there-and-then, i.e. past and future, experience and strategy. It should mind the danger to cheer for the rat race of self-optimizing and increasing efficiency. b) Mobile communication is influencing the organisation of work. Legal regulations often are not implemented in organisations or do not match the tasks. Organisations find it difficult even to find rules, because there are many contradictions like global work processes, client’s expectations of quick response, or downsizing of office assistants. Nevertheless, for organisations in both competition concerns as issues of workplace health promotion it is advisable to conduct clarification processes about availability times. As the branches of organisations like service, production, or distribution have to deal with different requirements and conditions, it is difficult to find one solution for all. This is why enterprises mostly do not find an agreement on availability or put it very vacuous or ambiguous. At first the task of supervision and coaching could be to uncover this area of conflict. The next step should be to make it discussable. c) Both mentioned categories, i.e. individual and organisation, also refer to changes in society. Sociologists are trying to describe a so called ‘Generation Y’ (aka Millenials, digital natives). They are ascripted to be seeking for happiness but also to be highly educated, strongly digitally connected and willing to work. But is it just a perfectly internalized intrapreneuship? Or are there indeed different attitudes towards work allowing them to dissolve boundaries between work and non-work time? Will this digitally generated ubiquity of global communication produce a new concept of boundless work and life? And what does this new concept of dissolving boundaries imply for supervision and coaching? References: - Walpuski, V. J. (2014): Smart Devices in Organisationen – Von Regelungen für die Allgegenwärtigkeit von computergestützter Kommunikation. In: Organisationsberatung Supervision Coaching OSC (2014) 21:99–114, DOI 10.1007/s11613-014-0359-z - Walpuski, V. J. (2013): Always on. Vom Umgang mit der ständigen Erreichbarkeit. In: Supervision. Mensch – Arbeit – Organisation, 4/2013, p. 32-38. - Walpuski, V. J. (2013): „work hard - play hard“, in: Supervision. Mensch – Arbeit – Organisation, 2/2013, p. 6265. - www.orevo.de , [email protected]

© Copyright 2026