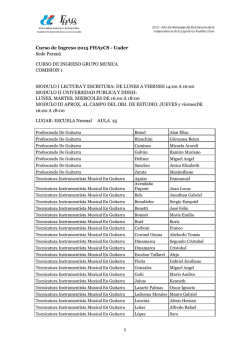

Valeria Mannoia - Portal de Revistas UN