Endovascular Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke May Be Safely

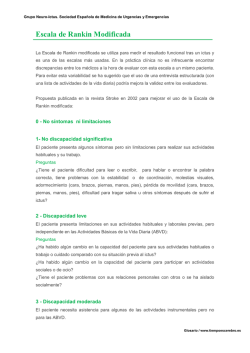

Endovascular Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke May Be Safely Performed With No Time Window Limit in Appropriately Selected Patients Alex Abou-Chebl, MD Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 9, 2016 Background and Purpose—The traditional time window for acute ischemic stroke intra-arterial therapy (IAT) is ⬍6 hours, which is based on pharmacological thrombolysis without penumbral imaging. This study was conducted to determine the safety of patient selection for IAT based on perfusion mismatch rather than time. Methods—A cohort of consecutive patients treated with IAT was identified by database review. Patients were selected for IAT based on the presence of perfusion mismatch using CT perfusion or MRI regardless of stroke duration. Thrombolytics were minimized after 6 hours in favor of mechanical embolectomy or angioplasty⫾stenting. Outcomes (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, modified Rankin Scale) were assessed by independent examiners. A multivariate analysis was performed to compare those treated ⬍6 hours (early) with those treated ⬎6 hours (late). Results—Fifty-five patients (mean National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale⫽19.7⫾5.7) were treated, 34 early and 21 late, with mean time-to-intervention of 3.4⫾1.6 hours and 18.6⫾16.0 hours, respectively. Thrombolysis In Myocardial Ischemia 2 or 3 recanalization was achieved in 82.8% early and 85.7% late patients (P⫽1.0). Intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in 25.5% overall, but symptomatic intracerebral hemorrhage occurred in 8.8% of the early and 9.5% of the late patients (P⫽1.0). Thirty-day mortality was similar (29.4% versus 23.8%, P⫽0.650). At 3 months, 41.2% and 42.9%, respectively, achieved a modified Rankin Scale ⱕ2 (P⫽0.902). Only presenting National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale was a predictor of modified Rankin Scale ⱕ2 (OR 0.794[95% CI 0.68 to 0.92], P⫽0.009) and death (adjusted OR 1.29[95% CI 1.04 to 1.59], P⫽0.019). Conclusions—In appropriately selected patients, IAT for acute ischemic stroke can be performed safely regardless of stroke duration. The concept of an acute ischemic stroke treatment window for IAT should be re-evaluated with a clinical trial selecting patients with perfusion mismatch. (Stroke. 2010;41:00-00.) Key Words: acute 䡲 endovascular therapy 䡲 perfusion imaging 䡲 reperfusion 䡲 stroke 䡲 thrombolytic therapy T raditionally, patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) have not been treated with intra-arterial revascularization therapy (IAT) beyond 6 hours due to the perceived lack of benefit and increased risk of intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). This concept is based on anecdotal experience with pharmacological thrombolysis and few randomized clinical trial data.1 With modern imaging studies that assess the ischemic penumbra and the availability of mechanical devices for clot removal, it may be possible to treat patients beyond the 6-hour treatment window without increasing the risk of ICH.2 The theoretical justification for this approach is that by limiting recanalization to those patients with minimal or small completed infarcts and large areas of perfusion mismatch, neuronal function may be spared without increasing the ICH risk, whereas revascularization of mostly infarcted tissue does not result in significant neuronal recovery and increases the risk of ICH because of associated endothelial, vascular and blood– brain barrier injury. Furthermore, phar- macological agents, particularly fibrinolytics, may have an increased propensity to cause ICH.1,3– 6 A few case series have reported treatment beyond the 6-hour window suggesting it may be feasible to treat patients presenting late.7,8 Due to the significant number of patients with AIS presenting outside the 6-hour time window at the author’s institution, an IAT protocol was developed using primarily CT, CT angiography, and CT perfusion imaging to select patients regardless of the time window. This retrospective study was conducted to assess the safety of this approach. Materials and Methods A prospectively collected and Institutional Review Board-approved database of all patients with AIS was retrospectively reviewed to identify a cohort of consecutive patients treated between March 2007 and April 2009 with IAT. All IAT was carried out by the author. The decision to initiate IAT was based on the clinical diagnosis of AIS with National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) ⱖ10 or severe aphasia, the absence of acute hypodensity on CT involving Received January 14, 2010; final revision received March 5, 2010; accepted March 25, 2010. From the Department of Neurology, University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, Ky. Correspondence to Alex Abou-Chebl, MD, Department of Neurology, Room 114, University of Louisville School of Medicine, 500 S Preston Street, Louisville, KY 40202. E-mail [email protected] © 2010 American Heart Association, Inc. Stroke is available at http://stroke.ahajournals.org DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.578997 1 2 Stroke September 2010 Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 9, 2016 more than one third of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) territory or more than half of the brain stem, the absence of any ICH on CT, the presence of a perfusion mismatch, and in patients presenting ⬍3 hours, a contraindication to intravenous tissue plasminogen activator. Perfusion mismatch was defined by the presence of a low cerebral blood flow region that measured ⱖ20% of the low cerebral blood volume region. IAT was not performed if the core infarct based on cerebral blood volume maps was more than one third of the MCA territory. Patients with brain stem ischemia ⬎6 hours in duration were defined as having perfusion mismatch if the clinical deficit was disproportionately more severe than the diffusionweighted imaging lesions. Time to treatment was defined as the time from stroke onset to initiation of IAT. Age ⬎80 years, hypertension ⬎220/120 mm Hg, hyperglycemia ⬎300 mg/dL, and underlying dementia were considered as relative contraindications to pharmacological IAT. All patients had CT, CT angiography, and CT perfusion within 15 minutes of arrival regardless of renal function. The CT angiography images were obtained using helical 0.75-mm thick scans at 0.5-mm intervals after injection of 100 mL of contrast at 4 mL/s. The CT perfusion images were acquired after the injection of 40 mL of contrast at 8 mL/s with 40 sequential acquisitions at 1-second intervals, each consisting of 2 adjacent 10-mm thick slices. Six-Fr femoral access was obtained in all patients followed by administration of 2000 to 3000 U of heparin. The decision to proceed with IAT was made after angiography of the affected vessel. If the use of the Merci(Concentric Medical Inc, Mountain View, Calif) system was likely, then the 6-Fr sheath was exchanged for an 8-Fr sheath. For intra-arterial thrombolysis as first treatment, tissue plasminogen activator was given in multiple boluses over 15 to 30 minutes directly into the thrombus for a maximum of 20 mg. Additionally, abciximab, 2 to 10 mg, was given directly into the thrombus if atherothrombosis was the likely etiology. If no recanalization occurred in 30 minutes, then mechanical recanalization was attempted. Mechanical embolectomy was performed with either the Merci Retriever with proximal occlusion through the Merci 8-Fr guide catheter or the Penumbra System (Penumbra Medical Inc, Alameda, Calif). If complete recanalization was not achieved within the first 30 to 60 minutes, then either thrombolytics or abciximab, if they had not already been given, were given up to the previously mentioned maximum doses. After 3 unsuccessful Merci passes or the use of ⬎2 Merci devices, the Penumbra system was used and vice versa for the Penumbra system. Angioplasty and stenting were planned as first-line treatment if an underlying atherosclerotic lesion was highly likely or if the other approaches failed. An undersized angioplasty balloon was used at nominal pressures. If an underlying stenosis was confirmed by the presence of a “waist” on the balloon, lesion irregularity characteristic of atherosclerosis, or marked lesion recoil was present, then a Vision (Abbott Vascular, Abbott Park, Ill) stent was deployed at nominal atmospheres for intracranial lesions or an approved carotid stent was deployed for proximal internal carotid artery lesions. If stent deployment was expected before the procedure, 600 mg clopidogrel and 325 mg aspirin were given through a nasogastric tube; otherwise, an abciximab half-weight-based bolus (approximately 8 to 12 mg) was given intra-arterially before stent placement (except if given earlier) followed by postprocedural 600 mg clopidogrel and 325 mg aspirin. Stenting was avoided if there was a large acute infarct on baseline CT or if thrombolytics were used. Cases were performed under local anesthesia with judicious (25 to 100 g) fentanyl and (1 to 4 mg) midazolam for severe agitation or discomfort. Comatose patients unable to maintain their airway underwent endotracheal intubation with propofol sedation and paralytics. Systolic blood pressures were maintained between 160 and 200 mm Hg except in those who received intravenous tissue plasminogen activator in whom it was kept ⱕ185/110 mm Hg. Fluid boluses, phenylephrine, -blockers, and nicardipine were used as needed. After restoration of perfusion or for those suspected of having intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH), systolic blood pressure was immediately lowered to 90 to 120 mm Hg. In those cases in which no or incomplete recanalization was achieved, the systolic blood pressure was kept at 150 to 180 mm Hg. Two hours after the start of the intervention or if patients had clinical deterioration, an intraprocedural CT (DynaCT; Siemens Medical Systems, Inc) was performed. If the CT was negative for ICH, then the interventional procedure was continued when appropriate but if positive, the procedure was terminated and corrective measures taken (ie, rapid lowering of systolic blood pressure ⬍120 mm Hg, infusion of 20 to 30 mg protamine sulfate, platelet transfusion to reverse antiplatelets, and fresh–frozen plasma if thrombolytics were given). Outcome Assessment Endovascular outcome was assessed using the Thrombolysis In Myocardial Ischemia scale with a score of 2 or 3 considered as recanalization success.9 ICH was defined using the European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study classification.10 All patients were examined by an independent vascular neurologist or stroke nurse practitioner in-hospital and at follow-up, who measured outcomes with the NIHSS and modified Rankin Scale. Patients unable to return to the clinic were contacted by telephone (as part of routine care) to assess their neurological function. Statistical Analysis SAS Version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) was used for all data analysis. In the univariate analysis, all categorical variables were analyzed by Pearson 2 or Fisher exact tests. When comparing late versus early groups, the distribution of continuous variables was examined and independent sample t tests or Mann-Whitney U tests were performed as appropriate. Multiple logistic regression using crude ORs, adjusted ORs, and 95% CIs was computed to assess time-to-treatment association with the various outcomes after controlling for pertinent clinical covariates. Outcome variables consisted of modeling recanalization success, death, dichotomized modified Rankin Scale (ⱕ2 versus ⱖ3), and symptomatic and asymptomatic ICH. Time to treatment was dichotomized into early (0 to 6 ours) or late (ⱖ6 hours) and for a subanalysis, early was redefined as 0 to 8 hours and late as ⬎8 hours. The covariates included recanalization method (pharmacological, embolectomy, angioplasty/stenting, and combination therapy), site of occlusion (internal carotid artery, MCA, tandem internal carotid artery and MCA, or vertebrobasilar), dichotomized recanalization (unsuccessful [Thrombolysis In Myocardial Ischemia 0 to 1] versus successful [Thrombolysis In Myocardial Ischemia 2 to 3]), and presenting NIHSS. Results A total of 55 patients were treated, 34 early and 21 late. The mean presenting NIHSS was 19.7⫾5.7 (range, 7 to 36). The mean time to treatment was 9.2⫾12.3 hours (range, 1 to 68 hours), but 3.4⫾1.6 hours and 18.6⫾16.0 hours in the early and late groups, respectively; median time to treatment was 5 hours overall and 3.25 hours and 12 hours, respectively. Cardioembolism was the leading stroke cause in the early group (54.8% versus 29.2%), whereas atherothrombosis was more common in the late group (29% versus 45.8%, respectively), P⫽0.199. The proportion treated with thrombolysis was significantly higher in the early group, 58.7% versus 23.8% (P⫽0.035), whereas angioplasty/stenting was more common in the late group, 26.5% versus 57.1% (P⫽0.023). Table 1 summarizes the patient characteristics and procedural details. Successful recanalization was achieved in 84.0% of all patients (82.8% early and 85.7% late, P⫽1.0). ICH occurred in 25.5% and symptomatic ICH was seen in 9.1% (8.8% early versus 9.5% late, P⫽1.0). At 30 days, mortality was similar between the 2 groups (29.4% early versus 23.8% late, Abou-Chebl Table 1. Patient Characteristics and Procedural Details No. (%), Mean⫾SD Patients Early Late Overall 34 21 55 Age, years 63.4⫾16.2 59.4⫾17.2 Females P⬍0.1 62⫾16.6 18 (52.9%) 8 (38%) 26 (47.3%) 3.4⫾1.6 18.6⫾16.0 9.2⫾12.3 P⫽0.0000001 NIHSS 20.9⫾5.5 17.8⫾5.5 19.7⫾5.7 P⫽0.048 Procedural Outcomes and Complications No. (%) Early Late Overall P TIMI 2 or 3 28 (82.8%) 18 (85.7%) 46 (84%) 1 TIMI 3 14 (41.2%) 10 (47.6%) 24 (43.6%) 0.783 9 (26.5%) 5 (23.8%) 14 (25.5%) 0.905 MCA 15 (44.1%) 8 (38.1%) 23 (41.8%) ICA 4 (11.8%) 4 (19%) 8 (14.5%) Tandem ICA/MCA 11 (32.4%) 2 (9.5%) 13 (23.6%) Vertebrobasilar 4 (11.8%) 7 (33.3%) 11 (20%) 24 (70.5%) 20 (95.2%) 44 (80%) Intracerebral Hemorrhage* Occlusion ASPECTS score Table 2. 3 Recanalization Time to treatment, hours Any early CT changes Acute Stroke Treatment Without a Time Window All Symptomatic Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 9, 2016 8.4⫾1.5 8.1⫾1.4 Range* 5–10 6–10 Median 8 8 3 (8.8%) 2 (9.5%) 5 (9.1%) 8.1⫾6.7 5.5⫾5.9 7⫾6.4 0.19 10 (29.4%) 5 (23.8%) 15 (27.3%) 0.65 All 14 (41.2%) 9 (42.9%) 23 (41.8%) 0.902 Survivors 14 (60.9%) 9 (56.3%) 23 (57.5%) 0.896 Postoperative change in NIHSS Death at 30 days P⫽0.082 8.3⫾1.4 8 1 Modified Rankin Scale ⱕ2 at 3 months *European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study classification. TIMI indicates Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction grade. Treatment Thrombolysis 20 (58.8%) Intravenous 7 (20.5%) Intra-arterial 13 (38.2%) Embolectomy 23 (67.6%) Angioplasty/ stenting 9 (26.5%) Combination 19 (55.9%) 5 (23.8%) 25 (45.4%) P⫽0.035 0 7 (12.7%) P⫽0.036 5 (23.8%) 18 (32.7%) 13 (61.9%) 36 (65.5%) 12 (57.1%) 21 (38.2%) P⫽0.023 10 (47.6%) 29 (52.7%) *Only 2 patients in each group ⬍7. ICA indicates internal carotid artery; ASPECTS, Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score. P⫽0.65). Overall, 41.8% achieved an modified Rankin Scale ⱕ2 at 3 months, 41.2% in the early group and 42.9% in the late group (P⫽0.902). Table 2 lists the outcomes and complications. In univariate analysis and multivariate modeling, only presenting NIHSS, not time to treatment or recanalization method, was a predictor of modified Rankin Scale ⱕ2 (adjusted OR 0.794 [95% CI 0.68 to 0.92], P⫽0.009) and death (adjusted OR 1.29 [95% CI 1.04 to 1.59], P⫽0.019), although successful recanalization might also have had an influence (adjusted OR 5.28 [95% CI 0.56 to 49.65], P⫽0.074). The results were unchanged when only anterior circulation strokes or, in separate analysis, isolated MCA occlusions were considered and they were similarly unchanged when the early group was redefined as 0 to 8 hours. Discussion Early recanalization is the most effective treatment for AIS, yet poorly timed recanalization is a major predictor of ICH, which has been the major obstacle limiting widespread use of recanalization therapy. For patients treated with intravenous tissue plasminogen activator, the effective time window is 3 to 4.5 hours, although the major clinical benefit is in those receiving therapy within 90 minutes.11,12 The time window is longer, up to 6 hours, in patients treated with IAT, offering a robust clinical benefit but with an increased risk of ICH.1 This apparent time dependence has been a fundamental principal of stroke neurology. Yet, the author and his colleagues have anecdotal cases treated beyond 6 hours who had excellent clinical outcomes.7,8,13,14 This current study suggests that in select patients with AIS with potentially salvageable brain tissue defined by CT perfusion (anterior circulation) or clinical–MRI mismatch (posterior circulation), IAT beyond 6 hours is feasible and safe with no increase in the risk of ICH or death. Moreover, this approach may be as effective as ⬍6-hour IAT. The safety of IAT in the late group in this series may have been due to several factors. First, and likely most important, is the selection of patients with perfusion imaging. Numerous preclinical studies and clinical trials have shown that reperfusion in the presence of a large perfusion mismatch and small necrotic core results in brain tissue salvage,15 whereas reperfusion of necrotic core in the absence of perfusion mismatch is ineffective and may increase the risk of ICH.16 Second, in this series, pharmacological thrombolysis was kept to a minimum, especially in those treated in the late group. There are data to support this approach, not the least of which are the intravenous thrombolysis trials that have clearly shown a relatively short time window for intravenous thrombolysis safety.11,12,17 Animal models have also shown that fibrinolytics, especially tissue plasminogen activator, are associated with a higher propensity to cause ICH independent of their recanalization efficacy.5 Other factors include the individualization of the therapy (ie, thrombolysis, embolectomy, or stenting) to each patient taking into account the known factors that predispose to ICH (ie, hyperglycemia, hypertension, age, size of necrotic core, etc) as well as probable stroke etiology.13,17,18 In general, randomized trials have not taken all of these factors into account when determining type and dosage of therapy, but rather such characteristics were exclusion criteria or were not considered in the treatment algorithm. The author has previously reported on this multimodal approach and subsequently larger 4 Stroke September 2010 Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 9, 2016 series have also shown that a multimodal approach may be more efficacious than fibrinolysis alone.13,17,19 The proportion of patients treated with stents was higher in the late group. This was expected because stenting was reserved for those with an underlying atherosclerotic stenosis and there was an overrepresentation of atherosclerotic occlusions in the late group. The proportion of atherosclerotic strokes was also higher than would have been expected based on the prevalence of large vessel atherosclerosis in AIS in the stroke belt.20 In this series, the late group fared better than would be expected based on duration of ischemia, which in the multivariate analysis was not related to stenting, although the number treated with stenting was small, which likely affected the ability to detect a benefit. The benefit could have been due to, as discussed previously in this article, less neurotoxicity from fibrinolytics. The underlying pathogenesis of the occlusion could also be the explanation because patients with underlying atherosclerotic stenoses likely had developed some degree of chronic pial or other collaterals and therefore were more likely to progress slowly and present later than those with embolic occlusion and they may also have had ischemic preconditioning increasing tolerance to ischemia21,22; the latter could explain in part the lower NIHSS scores in the late group. This finding is of importance because approximately 20% of ischemic strokes are due to large vessel atherosclerosis with 8% to 10% due to intracranial atherosclerosis.23 Furthermore, it is reasonable to postulate that mechanical embolectomy devices (eg, Merci and Penumbra) may not be as safe or effective in patients with an underlying stenosis, which may prevent clot retrieval, increase the risk of vessel injury, or predispose to reocclusion and clinical deterioration. It therefore may be important to attempt to determine the cause of the vascular occlusion before deciding on which endovascular approach to attempt and to consider stenting in those who present late. This concept that therapy be based on known pathophysiological mechanisms has not been systematically studied in the setting of AIS and in the ultra-acute setting determining the etiology of a large vessel occlusion may not be possible; therefore, this approach requires validation. This is also relevant because if stents are placed, patients will need dual antiplatelet therapy acutely as well as chronically and this can increase the risk of ICH.24 In this series, such an association was not found, but the number of patients treated was small. The limitations of this study are the retrospective nature of the database review and small sample size. The latter limits the ability to derive statistically significant results from the data and the ability to correct for differences between the 2 groups. However, all outcomes were measured by independent clinicians who documented the data prospectively as part of the standard of care for all patients with stroke at our institution. Because all patients treated were included in this series, the bias should have been minimized. Another limitation is the relatively higher number of vertebrobasilar occlusions in the late group, although the majority of patients treated had anterior circulation AIS. This group of patients has been reported to have potentially longer treatment windows, possibly related to more robust collaterals or relative resistance of brain stem neurons to ischemia as well as a higher likelihood of atherosclerotic occlusions, which may allow for greater collaterals. Also, CT-based penumbral imaging is not adequate to assess the brain stem and the use of diffusion-weighted imaging– clinical mismatch has not been validated. Therefore, a study of just patients with anterior circulation strokes may have been more appropriate, although after excluding the vertebrobasilar group, the results of this study did not change. Another limitation of this study is that there is currently no consensus on what constitutes a penumbra and which imaging modality best defines it; an analysis that included outcomes data on patients not treated due to lack of perfusion mismatch would have strengthened the conclusions, but these data are not available. Lastly, based on the published mechanical embolectomy registries, some may argue that an 8-hour time window is a more appropriate definition of early IAT.2,6 A 6-hour cutoff was chosen for this study because the clinical outcomes of the patients studied in those registries have generally not been good and therefore it could not be assumed that IAT up to 8 hours was as safe as ⬍6-hour IAT. The latter is also supported by the results of the only randomized trial, Prolyse in Acute Cerebral Thromboembolism (PROACT) II, which had a 6-hour window and which is arguably the cleanest published data set of IAT.1 Nevertheless, when reanalyzed using an 8-hour cutoff, the results of the study were unchanged. Summary This study showed that multimodal IAT may be safely used to treat patients who present beyond the traditional 6-hour time window if they are selected based on the presence of perfusion mismatch. However, more data are needed to better define which imaging criteria best define mismatch in clinical practice followed by validation of this approach through larger prospective trials. Acknowledgments I acknowledge the invaluable assistance and expertise of the Stroke Team: Kerri Remmel, MD, Vincent Truong, MD, Rori Spray, ARNP, CNRN, Betsy Wise, ARNP, and Craig Zeigler, PhD. Disclosures A.A.-C. is on the speaker’s bureau for BMS/Sanofi Partnership and on the advisory board for Arterain Medical Inc. References 1. Furlan A, Higashida R, Wechsler L, Gent M, Rowley H, Kase C, Pessin M, Ahuja A, Callahan F, Clark WM, Silver F, Rivera F. Intra-arterial prourokinase for acute ischemic stroke. The PROACT II study: a randomized controlled trial. Prolyse in Acute Cerebral Thromboembolism. JAMA. 1999;282:2003–2011. 2. Smith WS, Sung G, Saver J, Budzik R, Duckwiler G, Liebeskind DS, Lutsep HL, Rymer MM, Higashida RT, Starkman S, Gobin YP, Frei D, Grobelny T, Hellinger F, Huddle D, Kidwell C, Koroshetz W, Marks M, Nesbit G, Silverman IE. Mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: final results of the Multi MERCI trial. Stroke. 2008;39: 1205–1212. 3. Nakano S, Iseda T, Yoneyama T, Kawano H, Wakisaka S. Direct percutaneous transluminal angioplasty for acute middle cerebral artery trunk occlusion: an alternative option to intra-arterial thrombolysis. Stroke. 2002;33:2872–2876. 4. Dijkhuizen RM, Asahi M, Wu O, Rosen BR, Lo EH. Rapid breakdown of microvascular barriers and subsequent hemorrhagic transformation after delayed recombinant tissue plasminogen activator treatment in a rat embolic stroke model. Stroke. 2002;33:2100 –2104. Abou-Chebl Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 9, 2016 5. Ning M, Furie KL, Koroshetz WJ, Lee H, Barron M, Lederer M, Wang X, Zhu M, Sorensen AG, Lo EH, Kelly PJ. Association between tPA therapy and raised early matrix metalloproteinase-9 in acute stroke. Neurology. 2006; 66:1550–1555. 6. The Penumbra Pivotal Stroke Trial: safety and effectiveness of a new generation of mechanical devices for clot removal in intracranial large vessel occlusive disease. Stroke. 2009;40:2761–2768. 7. Barnwell SL, Clark WM, Nguyen TT, O’Neill OR, Wynn ML, Coull BM. Safety and efficacy of delayed intraarterial urokinase therapy with mechanical clot disruption for thromboembolic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:1817–1822. 8. Abou-Chebl A, Vora N, Yadav JS. Safety of angioplasty and stenting without thrombolysis for the treatment of early ischemic stroke. J Neuroimaging. 2009;19:139 –143. 9. The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) trial. Phase I findings. TIMI Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:932–936. 10. Larrue V, von Kummer RR, Muller A, Bluhmki E. Risk factors for severe hemorrhagic transformation in ischemic stroke patients treated with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator: a secondary analysis of the European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study (ECASS II). Stroke. 2001;32: 438 – 441. 11. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581–1587. 12. Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, Davalos A, Guidetti D, Larrue V, Lees KR, Medeghri Z, Machnig T, Schneider D, von KR, Wahlgren N, Toni D. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317–1329. 13. Abou-Chebl A, Bajzer CT, Krieger DW, Furlan AJ, Yadav JS. Multimodal therapy for the treatment of severe ischemic stroke combining GPIIb/IIIa antagonists and angioplasty after failure of thrombolysis. Stroke. 2005;36:2286 –2288. 14. Grigoriadis S, Gomori JM, Grigoriadis N, Cohen JE. Clinically successful late recanalization of basilar artery occlusion in childhood: what are the odds? Case report and review of the literature. J Neurol Sci. 2007;260: 256 –260. 15. Wintermark M, Flanders AE, Velthuis B, Meuli R, van Leeuwen M, Goldsher D, Pineda C, Serena J, van der Schaaf I, Waaijer A, Anderson J, Nesbit G, Gabriely I, Medina V, Quiles A, Pohlman S, Quist M, Schnyder P, Bogousslavsky J, Dillon WP, Pedraza S. Perfusion-CT Acute Stroke Treatment Without a Time Window 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 5 assessment of infarct core and penumbra: receiver operating characteristic curve analysis in 130 patients suspected of acute hemispheric stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:979 –985. Gupta R, Yonas H, Gebel J, Goldstein S, Horowitz M, Grahovac SZ, Wechsler LR, Hammer MD, Uchino K, Jovin TG. Reduced pretreatment ipsilateral middle cerebral artery cerebral blood flow is predictive of symptomatic hemorrhage post-intra-arterial thrombolysis in patients with middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 2006;37:2526 –2530. Gupta R, Vora NA, Horowitz MB, Tayal AH, Hammer MD, Uchino K, Levy EI, Wechsler LR, Jovin TG. Multimodal reperfusion therapy for acute ischemic stroke: factors predicting vessel recanalization. Stroke. 2006;37:986 –990. Vora NA, Gupta R, Thomas AJ, Horowitz MB, Tayal AH, Hammer MD, Uchino K, Wechsler LR, Jovin TG. Factors predicting hemorrhagic complications after multimodal reperfusion therapy for acute ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:1391–1394. Lin R, Vora N, Zaidi S, Aleu A, Jankowitz B, Thomas A, Gupta R, Horowitz M, Kim S, Reddy V, Hammer M, Uchino K, Wechsler LR, Jovin T. Mechanical approaches combined with intra-arterial pharmacological therapy are associated with higher recanalization rates than either intervention alone in revascularization of acute carotid terminus occlusion. Stroke. 2009;40:2092–2097. Lackland DT, Bachman DL, Carter TD, Barker DL, Timms S, Kohli H. The geographic variation in stroke incidence in two areas of the southeastern stroke belt: the Anderson and Pee Dee Stroke Study. Stroke. 1998;29:2061–2068. Brandt T, von Kummer R, Muller-Kuppers M, Hacke W. Thrombolytic therapy of acute basilar artery occlusion. Variables affecting recanalization and outcome. Stroke. 1996;27:875– 881. Zhang J, Yang ZJ, Klaus JA, Koehler RC, Huang J. Delayed tolerance with repetitive transient focal ischemic preconditioning in the mouse. Stroke. 2008;39:967–974. Sacco RL, Kargman DE, Gu Q, Zamanillo MC. Race– ethnicity and determinants of intracranial atherosclerotic cerebral infarction. The Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Stroke. 1995;26:14 –20. Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, Cimminiello C, Csiba L, Kaste M, Leys D, Matias-Guiu J, Rupprecht HJ. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, doubleblind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:331–337. Endovascular Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke May Be Safely Performed With No Time Window Limit in Appropriately Selected Patients Alex Abou-Chebl Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 9, 2016 Stroke. published online July 22, 2010; Stroke is published by the American Heart Association, 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX 75231 Copyright © 2010 American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0039-2499. Online ISSN: 1524-4628 The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the World Wide Web at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/early/2010/07/22/STROKEAHA.110.578997.citation Data Supplement (unedited) at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/suppl/2012/03/12/STROKEAHA.110.578997.DC1.html Permissions: Requests for permissions to reproduce figures, tables, or portions of articles originally published in Stroke can be obtained via RightsLink, a service of the Copyright Clearance Center, not the Editorial Office. Once the online version of the published article for which permission is being requested is located, click Request Permissions in the middle column of the Web page under Services. Further information about this process is available in the Permissions and Rights Question and Answer document. Reprints: Information about reprints can be found online at: http://www.lww.com/reprints Subscriptions: Information about subscribing to Stroke is online at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org//subscriptions/ El tratamiento endovascular del ictus isquémico agudo puede realizarse de modo seguro sin límite de ventana temporal en pacientes adecuadamente seleccionados Alex Abou-Chebl, MD Antecedentes y objetivo—La ventana de tiempo tradicional para el tratamiento intraarterial (TIA) del ictus isquémico agudo es < 6 horas, y se basa en la trombólisis farmacológica sin exploración de imagen de la penumbra. Este estudio se llevó a cabo para determinar la seguridad de una selección de los pacientes para el TIA basada en el mismatch de perfusión en vez de en el tiempo. Métodos—Se identificó una cohorte de pacientes consecutivos tratados con TIA mediante la revisión de una base de datos. Los pacientes fueron seleccionados para el TIA en función de la presencia de un mismatch de perfusión en la TC o la RM, con independencia del tiempo de evolución del ictus. El uso de trombolíticos se minimizó a partir de las 6 horas, en favor de una embolectomía mecánica o una angioplastia±implantación de stent. Los resultados (escala National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, escala de Rankin modificada) fueron evaluados por evaluadores independientes. Se llevó a cabo un análisis multivariable para comparar a los pacientes tratados en un plazo < 6 horas (temprano) con los tratados en un plazo > 6 horas (tardío). Resultados—Se trató a un total de 55 pacientes (media de National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale = 19,7±5,7), 34 de forma temprana y 21 de forma tardía, con una media de tiempo hasta la intervención de 3,4±1,6 horas y 18,6±16,0 horas, respectivamente. Se alcanzó una recanalización de grado 2 ó 3 de Thrombolysis In Myocardial Ischemia en el 82,8% de los pacientes tratados de forma temprana y en un 85,7% de los tratados de forma tardía (p = 1,0). Se produjeron hemorragias intracerebrales en un 25,5% del total de los pacientes, pero las hemorragias intracerebrales sintomáticas se dieron en el 8,8% de los que recibieron un tratamiento temprano y en el 9,5% de los tratados de forma tardía (p = 1,0). La mortalidad a 30 días fue similar (29,4% frente a 23,8%, p = 0,650). A los 3 meses, el 41,2% y 42,9%, respectivamente, alcanzaron una puntuación en la escala de Rankin modificada ≤ 2 (p = 0,902). Tan solo la puntuación en la National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale en el momento de la presentación inicial tuvo valor predictivo para una puntuación de la escala de Rankin modificada ≤ 2 (OR 0,794 [IC del 95% 0,68 a 0,92], p = 0,009) y para la muerte (OR ajustada 1,29 [IC del 95% 1,04 a 1,59], p = 0,019). Conclusiones—En pacientes adecuadamente seleccionados, el TIA para el ictus isquémico agudo puede aplicarse de modo seguro con independencia del tiempo de evolución del ictus. El concepto de ventana de tratamiento del ictus isquémico agudo deberá ser reevaluado en un ensayo clínico en el que se seleccione a pacientes con mismatch de perfusión. (Traducido del inglés: Endovascular Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke May Be Safely Performed With No Time Window Limit in Appropriately Selected Patients. Stroke. 2010;41: 1996-2000.) Palabras clave: acute n endovascular therapy n perfusion imaging n reperfusion n stroke n thrombolytic therapy T radicionalmente, los pacientes con ictus isquémico agudo (IIA) no han sido tratados con un tratamiento de revascularización intraarterial (TIA) después de las 6 primeras horas, debido a la percepción de una falta de efectos beneficiosos y un aumento del riesgo de hemorragia intracerebral (HIC). Este concepto se basa en la experiencia testimonial existente con la trombólisis farmacológica y en pocos datos de ensayos clínicos aleatorizados1. Con las técnicas modernas de diagnóstico por la imagen que permiten valorar la penumbra isquémica y con la disponibilidad de dispositivos mecánicos para la extracción del coágulo, puede ser posible tratar a pacientes después de superada la ventana terapéutica de 6 horas sin aumentar el riesgo de HIC2. La justificación teórica de este enfoque es que, al limitar la recanalización a los pacientes con infartos mínimos o pequeños y áreas grandes de mismatch de perfusión, es posible preservar la función neuronal sin aumentar el riesgo de HIC, mientras que la revascularización de los tejidos más infartados no aporta una recuperación neuronal significativa y sí aumenta el riesgo de HIC debido a la lesión asociada del endotelio, el vaso sanguíneo y la barrera hematoencefálica. Además, los agentes farmacológicos, y en particular los fibrinolíticos, pueden tener una mayor propensión a causar HIC1,3-6. En unas pocas series de casos se ha descrito el tratamiento después de la ventana Recibido el 14 de enero de 2010; revisión final recibida el 5 de marzo de 2010; aceptado el 25 de marzo de 2010. Department of Neurology, University of Louisville School of Medicine, Louisville, Ky. Remitir la correspondencia a Alex Abou-Chebl, MD, Department of Neurology, Room 114, University of Louisville School of Medicine, 500 S Preston Street, Louisville, KY 40202. E-mail [email protected] © 2010 American Heart Association, Inc. Stroke está disponible en http://www.stroke.ahajournals.org 13 DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.578997 14 Stroke Abril 2011 temporal de 6 horas, y se ha sugerido que puede ser viable tratar a pacientes que acuden de forma tardía7,8. Dado el número significativo de pacientes con IIA que acuden al centro del autor después de la ventana temporal de 6 horas, se desarrolló un protocolo de TIA con el empleo fundamentalmente de TC, angio-TC y TC de perfusión, para seleccionar a los pacientes de manera independiente de la ventana temporal. Este estudio retrospectivo se llevó a cabo para evaluar la seguridad de dicho enfoque. Material y métodos Se efectuó una revisión retrospectiva de una base de datos prospectiva, autorizada por el comité ético, de todos los pacientes con IIA, con objeto de identificar una cohorte de pacientes consecutivos tratados entre marzo de 2007 y abril de 2009 con el empleo de TIA. Todos los TIA fueron realizados por el autor. La decisión de iniciar el TIA se basó en el diagnóstico clínico de IIA con una puntuación de la National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) ≥ 10 o con afasia grave, la ausencia de hipodensidad en la TC que afectara a más de un tercio del territorio de la arteria cerebral media (ACM) o más de la mitad del tronco encefálico, la ausencia de toda HIC en la TC, y la presencia de un mismatch de perfusión, y en los pacientes que acudían en un plazo < 3 horas, una contraindicación para el empleo de activador de plasminógeno tisular intravenoso. El mismatch de perfusión de definió por la presencia de una región de flujo sanguíneo cerebral bajo que medía ≥ 20% de la región de volumen sanguíneo cerebral bajo. No se aplicó el TIA si el núcleo del infarto evaluado en los mapas de volumen sanguíneo cerebral era mayor de un tercio del territorio de la ACM. En los pacientes con una isquemia de tronco encefálico de una duración > 6 horas, se definió la presencia de mismatch de perfusión si el déficit clínico era desproporcionadamente más grave que lo indicado por las lesiones en las imágenes de ponderación de difusión. El tiempo hasta el tratamiento se definió como el transcurrido desde el inicio del ictus hasta el inicio del TIA. La edad > 80 años, la hipertensión arterial > 220/120 mmHg, la hiperglucemia > 300 mg/dL y la demencia subyacente se consideraron contraindicaciones relativas para el TIA farmacológico. En todos los pacientes se obtuvo una TC, angio-TC o TC de perfusión en un plazo de 15 minutos tras su llegada, con independencia de la función renal. Las imágenes de angioTC se obtuvieron con el empleo de exploraciones helicoidales de 0,75 mm de grosor a intervalos de 0,5 mm, tras la inyección de 100 mL de contraste a 4 mL/s. Las imágenes de TC de perfusión se obtuvieron tras la inyección de 40 mL de contraste a 8 mL/s, con 40 adquisiciones secuenciales a intervalos de 1 segundo, cada una formada por 2 cortes adyacentes de 10 mm de grosor. Se estableció una vía de acceso femoral de 6 Fr en todos los pacientes, seguido de la administración de 2.000 a 3.000 U de heparina. La decisión de proceder al TIA se tomó tras la angiografía del vaso afectado. Si era probable el uso del sistema Merci (Concentric Medical Inc, Mountain View, Calif), se cambiaba la vaina de 6 Fr por una vaina de 8 Fr. Para la trombólisis intraarterial como primer tratamiento, se utilizó activador de plasminógeno tisular administrado en múlti- ples bolos a lo largo de 15 a 30 minutos, directamente en el trombo, con un máximo de 20 mg. Además, se administró abciximab, 2 a 10 mg, directamente en el trombo si la etiología probable era una aterotrombosis. Si no se obtenía una recanalización en 30 minutos, se intentaba una recanalización mecánica. Se llevó a cabo una embolectomía mecánica con el Merci Retriever con oclusión proximal mediante el catéter guía Merci 8-Fr o con el Penumbra System (Penumbra Medical Inc, Alameda, Calif). Si no se alcanzaba una recanalización completa en los primeros 30 a 60 minutos, se utilizaban trombolíticos o abciximab, si no se habían administrado ya, hasta las dosis máximas antes mencionadas. Después de 3 introducciones sin éxito del Merci o del uso de > 2 dispositivos Merci, se empleaba el sistema Penumbra y viceversa. Se programó una angioplastia e implantación de stent como tratamiento de primera línea en el caso de que fuera muy probable una lesión aterosclerótica subyacente o si otros métodos no habían dado resultado. Se utilizó un balón de angioplastia de calibre inferior al del vaso, inflándolo hasta la presión de referencia (nominal) para su tamaño. Si se confirmaba una estenosis subyacente por la presencia de una “cintura” en el balón, una irregularidad de la lesión característica de la aterosclerosis o una retracción intensa de la lesión, se utilizaba un stent Vision (Abbott Vascular, Abbott Park, Ill) que se desplegaba a su presión de expansión de referencia para lesiones intracraneales o se desplegaba un stent carotídeo aprobado para las lesiones de la arteria carótida interna proximal. Si se preveía el despliegue de un stent, antes de la intervención se administraban 600 mg de clopidogrel y 325 mg de ácido acetilsalicílico a través de una sonda nasogástrica; en otro caso, se administraba un bolo de abciximab basado en la mitad del peso (aproximadamente 8 a 12 mg) por vía intraarterial antes de la implantación del stent (excepto si se había administrado antes), seguido después de la intervención de 600 mg de clopidogrel y 325 mg de ácido acetilsalicílico. Se evitó la implantación de stents si había un infarto agudo grande en la TC basal o si se empleaban trombolíticos. Las intervenciones se realizaron bajo anestesia local, con un uso juicioso de fentanilo (25 a 100 µg) y de midazolam (1 a 4 mg) para la agitación o molestias intensas. En los pacientes comatosos que no eran capaces de mantener despejadas las vías aéreas, se utilizó intubación endotraqueal con sedación con propofol y parálisis. Se mantuvieron las presiones arteriales sistólicas entre 160 y 200 mmHg, excepto en los pacientes que fueron tratados con activador de plasminógeno tisular intravenoso, en los que se mantuvieron en valores ≤ 185/110 mmHg. Se utilizaron bolos de líquido, fenilefrina, betabloqueantes y nicardipino según las necesidades. Tras al restablecimiento de la perfusión o en los casos de sospecha de hemorragia intracerebral (HIC), se redujo inmediatamente la presión arterial sistólica a un valor de 90 a 120 mmHg. En los casos en los que no se alcanzó la recanalización o ésta fue incompleta, la presión arterial sistólica se mantuvo en 150 a 180 mmHg. Dos horas después del inicio de la intervención o si el paciente presentaba un deterioro clínico, se realizó una TC intraintervención (DynaCT; Siemens Medical Systems, Inc). Si la TC era negativa para HIC, se continuaba la intervención si ello era apropiado, pero si era positiva se interrumpía la in- Abou-Chebl El tratamiento endovascular del ictus isquémico agudo 15 Tabla 1. Características de los pacientes y detalles de la intervención Tabla 2. Resultados y complicaciones Número (%), media ± DE Número (%) Tratamiento Tratamiento temprano tardío Pacientes Edad, años 34 63,4 Global 21 16,2 59,4 P 0,1 55 17,2 62 Mujeres 18 (52,9%) 8 (38%) Tiempo hasta el tratamiento, horas 3,4 1,6 18,6 16,0 9,2 NIHSS 20,9 5,5 17,8 5,5 16,6 12,3 P 5,7 P 0,0000001 0,048 Oclusión ACM 15 (44,1%) ACI 4 (11,8%) 8 (14,5%) ACI/ACM en tándem 11 (32,4%) 2 (9,5%) 13 (23,6%) Vertebrobasilar 4 (11,8%) 7 (33,3%) 11 (20%) Cualquier alteración 24 (70,5%) temprana en la TC 20 (95,2%) 44 (80%) 1,5 8,1 1,4 Rango* 5–10 6–10 Mediana 8 8 8,3 Global TIMI 2 ó 3 28 (82,8%) 18 (85,7%) 46 (84%) 1 TIMI 3 14 (41,2%) 10 (47,6%) 24 (43,6%) 0,783 9 (26,5%) 5 (23,8%) 14 (25,5%) 0,905 3 (8,8%) 2 (9,5%) 5 (9,1%) 1 8,1 5,5 7 0,19 P Intracerebral Hemorragia* Todos Sintomáticos 8 (38,1%) 23 (41,8%) 4 (19%) Puntuación ASPECTS 8,4 Tratamiento tardío Recanalización 26 (47,3%) 19,7 Tratamiento temprano Cambio postoperatorio en la NIHSS Muerte a los 30 días P 0,082 1,4 6,7 5,9 6,4 10 (29,4%) 5 (23,8%) 15 (27,3%) 0,65 Todos 14 (41,2%) 9 (42,9%) 23 (41,8%) 0,902 Supervivientes 14 (60,9%) 9 (56,3%) 23 (57,5%) 0,896 Escala de Rankin modificada ≤2 a los 3 meses *Clasificación del European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study. TIMI indica grado de Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction. 8 Tratamiento Trombólisis 20 (58,8%) Intravenoso 7 (20,5%) 5 (23,8%) 25 (45,4%) P 0 7 (12,7%) P Intraarterial 13(38,2%) 5 (23,8%) 18 (32,7%) Embolectomía 23 (67,6%) 13 (61,9%) 36 (65,5%) Angioplastia/ 9 (26,5%) implantación de stent 12 (57,1%) 21 (38,2%) P Combinación 10 (47,6%) 29 (52,7%) 19 (55,9%) 0,035 0,036 0,023 *Solamente 2 pacientes en cada grupo < 7. ACI indica arteria carótida interna; ASPECTS, Alberta Stroke Program Early CT Score. tervención y se instauraban medidas correctoras (es decir, reducción rápida de la presión arterial sistólica a < 120 mmHg, infusión de 20 a 30 mg de sulfato de protamina, transfusiones de plaquetas para revertir la acción de los antiagregantes plaquetarios y plasma fresco congelado en caso de uso de trombolíticos). Evaluación de los resultados Los resultados endovasculares se evaluaron con la escala Thrombolysis In Myocardial Ischemia, considerando una puntuación de 2 ó 3 como indicativa del éxito de la recanalización9. La HIC se definió con la clasificación del European Cooperative Acute Stroke Study10. Todos los pacientes fueron examinados por un neurólogo vascular independiente o una enfermera de ictus en el hospital y en el seguimiento posterior, utilizando los criterios de valoración de la NIHSS y la escala de Rankin modificada. Se contactó telefónicamente (como parte de la asistencia ordinaria) con los pacientes que no pudieron regresar a la clínica, con objeto de evaluar su función neurológica. Análisis estadístico Se utilizó el programa SAS Versión 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) para todos los análisis de los datos. En el análisis univariable, todas las variables categóricas se analizaron con la prueba de χ2 de Pearson o la prueba exacta de Fisher. Al comparar los grupos de tratamiento tardío frente a tratamiento temprano, se examinó la distribución de las variables continuas y se utilizaron pruebas de t para muestras independientes o pruebas de U de Mann-Whitney, según fuera apropiado. Se calculó una regresión logística múltiple, utilizando OR brutas, OR ajustadas e IC del 95% para valorar la asociación de tiempo y tratamiento con los diversos resultados evaluados, tras introducir un control respecto a las covariables clínicas pertinentes. Las variables de valoración de los resultados consistieron en una modelización del éxito de la recanalización, la muerte, la escala de Rankin modificada dicotomizada (≤ 2 frente a ≥ 3) y las HIC sintomáticas y asintomáticas. El tiempo hasta el tratamiento se dicotomizó en las categorías de tratamiento temprano (0 a 6 horas) o tardío (≥ 6 horas) y para un subanálisis, el tratamiento temprano se redefinió como el aplicado en un plazo de 0 a 8 horas y el tardío como el aplicado después de un periodo > 8 horas. Las covariables consideradas fueron el método de recanalización (farmacológico, embolectomía, angioplastia/implantación de stents, y tratamiento combinado), la localización de la oclusión (arteria carótida interna, ACM, lesión en tándem de arteria carótida interna y ACM, o vertebrobasilar), la recanalización dicotomizada (ineficaz [Thrombolysis In Myocardial Ischemia 0 a 1] frente a eficaz [Thrombolysis In Myocardial Ischemia 2 a 3]), y la NIHSS en el momento de la presentación inicial. Resultados Se trató a un total de 55 pacientes, 34 de forma temprana y 21 de forma tardía. La media de puntuación de la NIHSS en el momento de la presentación inicial fue de 19,7±5,7 (rango, 7 a 36). La media de tiempo hasta el tratamiento fue de 9,2±12,3 horas (rango, 1 a 68 horas), pero en los grupos de tratamiento temprano y tardío fue de 3,4±1,6 horas y 18,6±16,0 horas, respectivamente; la mediana de tiempo hasta el tratamiento fue de 5 horas globalmente y de 3,25 horas y 12 horas, respectivamente, en los dos grupos. El embolismo cardiaco fue la principal causa del ictus en el grupo de trata- 16 Stroke Abril 2011 miento temprano (54,8% frente a 29,2%), mientras que en el grupo de tratamiento tardío fue más común la aterotrombosis (29% frente a 45,8%, respectivamente), p=0,199. La proporción de pacientes tratados con trombólisis fue significativamente mayor en el grupo de tratamiento temprano, con un 58,7% frente a 23,8% (p = 0,035), mientras que la angioplastia/implantación de stent fue más común en el grupo de tratamiento tardío, con un 26,5% frente a 57,1% (p = 0,023). En la Tabla 1 se resumen las características de los pacientes y la información sobre la intervención. Se alcanzó una recanalización eficaz en el 84,0% del total de pacientes (82,8% con el tratamiento temprano y 85,7% con el tardío, p = 1,0). Se produjeron HIC en un 25,5% e HIC sintomáticas en un 9,1% de los casos (8,8% con el tratamiento temprano frente a 9,5% con el tardío, p = 1,0). A los 30 días, la mortalidad fue similar en los 2 grupos (29,4% con el tratamiento temprano frente a 23,8% con el tardío, p = 0,65). Globalmente, el 41,8% de los pacientes alcanzaron una puntuación de la escala de Rankin modificada ≤ 2 a los 3 meses, y esto se produjo en el 41,2% de los del grupo de tratamiento temprano y el 42,9% de los de tratamiento tardío (p = 0,902). En la Tabla 2 se indican los resultados y las complicaciones. En el análisis univariable y en la modelización multivariable, solamente la NIHSS en el momento de la presentación inicial, pero no en cambio el tiempo hasta el tratamiento ni el método de recanalización, mostró un valor predictivo respecto a la obtención de una puntuación de la escala de Rankin modificada ≤ 2 (OR ajustada 0,794 [IC del 95% 0,68 a 0,92], p = 0,009) y respecto a la mortalidad (OR ajustada 1,29 [IC del 95% 1,04 a 1,59], p = 0,019), aunque la recanalización eficaz podría haber tenido también influencia (OR ajustada 5,28 [IC del 95% 0,56 a 49,65], p = 0,074). Los resultados no se modificaron al considerar solamente los ictus de circulación anterior, ni en los análisis por separado realizados para las oclusiones de la ACM aisladas, y no se modificaron tampoco al redefinir el grupo de tratamiento inicial como el correspondiente al periodo de 0 a 8 horas. Discusión La recanalización temprana es el tratamiento más efectivo para el IIA, aunque su aplicación en el momento inadecuado es un importante predictor de la HIC, lo cual ha constituido el principal obstáculo que ha limitado un uso generalizado del tratamiento de recanalización. En los pacientes tratados con activador de plasminógeno tisular por vía intravenosa, la ventana temporal efectiva es de 3 a 4,5 horas, aunque el principal beneficio clínico es el que se obtiene en los pacientes tratados en un plazo de 90 minutos11,12. La ventana temporal es más amplia, de hasta 6 horas, en los pacientes tratados con el TIA, que aporta un beneficio clínico sólido, pero con un aumento del riesgo de HIC1. Esta aparente dependencia temporal ha sido uno de los principios fundamentales en la neurología del ictus. Sin embargo, el autor y sus colegas tienen experiencia de casos testimoniales tratados después de las 6 horas que han presentado unos resultados clínicos excelentes7,8,13,14. El presente estudio sugiere que, en pacientes con IIA seleccionados que tienen un tejido cerebral que puede ser salvado, según lo definido por la TC de perfusión (circulación anterior) o el mismatch clínico-RM (circulación posterior), el TIA aplicado después de las 6 horas es viable y seguro, y no comporta un aumento del riesgo de HIC o muerte. Además, este enfoque puede ser igual de efectivo que el TIA aplicado antes de las 6 horas. La seguridad del TIA en el grupo de tratamiento tardío de esta serie puede haberse debido a varios factores. En primer lugar, y probablemente ello sea lo más importante, la selección de los pacientes con las imágenes de perfusión. Numerosos estudios preclínicos y ensayos clínicos han demostrado que la reperfusión en presencia de un mismatch de perfusión grande y un núcleo necrótico pequeño conduce a la salvación del tejido cerebral15, mientras que la reperfusión del núcleo necrótico en ausencia de mismatch de perfusión es ineficaz y puede aumentar el riesgo de HIC16. En segundo lugar, en esta serie, la trombólisis farmacológica se mantuvo en un mínimo, sobre todo en los pacientes tratados de forma tardía. Hay datos que respaldan este enfoque, y no son los menos importantes los de los ensayos de la trombólisis intravenosa que han puesto claramente de manifiesto una ventana temporal relativamente corta para la seguridad de la trombólisis intravenosa11,12,17. En modelos animales se ha observado también que los fibrinolíticos, y especialmente el activador de plasminógeno tisular, se asocian a una mayor propensión a causar una HIC de manera independiente de su eficacia de recanalización5. Otros factores son la individualización del tratamiento (es decir, trombólisis, embolectomía o implantación de stents) de cada paciente teniendo en cuenta los factores conocidos que predisponen a la HIC (es decir, hiperglucemia, hipertensión arterial, edad, tamaño del núcleo necrótico, etc.) así como la probable etiología del ictus13,17,18. En general, los ensayos aleatorizados no han tenido en cuenta todos estos factores al determinar el tipo y la dosis de tratamiento, sino que estas características han sido más bien criterios de exclusión o no se han tenido en cuenta en el algoritmo de tratamiento. El autor ha presentado anteriormente este enfoque multimodal y en series más amplias posteriores se ha observado también que un enfoque multimodal puede ser más eficaz que la fibrinólisis sola13,17,19. La proporción de pacientes tratados con stents fue mayor en el grupo de tratamiento tardío. Esto era previsible, puesto que los stents se reservan para los pacientes con lesiones ateroscleróticas subyacentes y las oclusiones ateroscleróticas estaban sobrerrepresentadas en el grupo de tratamiento tardío. La proporción de ictus ateroscleróticos fue también superior a la que hubiera sido de esperar en función de la prevalencia de la aterosclerosis de grandes vasos en el IIA en la franja del ictus20. En esta serie, el grupo de tratamiento tardío tuvo una evolución mejor de lo que hubiera sido de prever en función de la duración de la isquemia, que en el análisis multivariable no estuvo relacionada con la implantación de stents, si bien el número de pacientes a los que se aplicó este tratamiento es bajo, lo cual afectó probablemente a la capacidad de detectar un efecto favorable. El efecto beneficioso podría haberse debido, como se ha comentado antes en este artículo, a la menor neurotoxicidad por fibrinolíticos. La patogenia subyacente de la oclusión podría ser también una explicación, ya que los pacientes con estenosis ateroscleróticas subyacentes habían de- Abou-Chebl El tratamiento endovascular del ictus isquémico agudo 17 sarrollado probablemente un cierto grado de colaterales crónicas de la piamadre u otras, y por tanto era más probable que progresaran lentamente y acudieran más tarde que los pacientes con oclusiones embólicas; además, y pueden haber tenido también un preacondicionamiento isquémico que mejorara la tolerancia a la isquemia21,22; esto último podría explicar en parte las puntuaciones NIHSS más bajas observadas en el grupo de tratamiento tardío. Esta observación es importante, ya que aproximadamente un 20% de los ictus isquémicos se deben a aterosclerosis de vasos grandes y un 8% a 10% se deben a aterosclerosis intracraneales23. Además, parece razonable proponer que los dispositivos de embolectomía mecánica (por ejemplo, Merci y Penumbra) puedan no ser seguros o eficaces en pacientes con una estenosis subyacente, que puede impedir la extracción del coágulo, aumentar el riesgo de lesión vascular o predisponer a la reoclusión y el deterioro clínico. Así pues, puede ser importante intentar determinar la causa de la oclusión vascular antes de decidir qué método endovascular intentar y contemplar el uso de stents en los pacientes que acuden tardíamente. Este concepto de que el tratamiento se basa en mecanismos fisiopatológicos conocidos no se ha estudiado de manera sistemática en el contexto de los IIA; y en el contexto ultraprecoz puede no ser posible determinar la etiología de una oclusión de un vaso grande; así pues, este enfoque requiere validación. Esto es relevante también, ya que si se implantan stents, los pacientes necesitarán un tratamiento antiagregante plaquetario combinado doble de forma aguda y también crónica, y ello puede aumentar el riesgo de HIC24. En esta serie, no se observó una asociación de este tipo, pero el número de pacientes tratados fue bajo. Las limitaciones de este estudio son el carácter retrospectivo de la revisión de la base de datos y el bajo tamaño muestral. Esto último limita la posibilidad de obtener resultados estadísticamente significativos a partir de los datos y la capacidad de corregir las diferencias existentes entre los dos grupos. Sin embargo, todos los resultados fueron evaluados por clínicos independientes que documentaron los datos de forma prospectiva como parte de la asistencia estándar de todos los pacientes con ictus de nuestro centro. Dado que todos los pacientes tratados se incluyeron en la serie, el sesgo debe haberse reducido al mínimo. Otra limitación es el número relativamente más elevado de oclusiones vertebrobasilares en el grupo de tratamiento tardío, aunque la mayoría de los pacientes tratados tenían IIA de la circulación anterior. Se ha descrito que este grupo de pacientes puede tener una ventana temporal para el tratamiento más amplia, posiblemente a causa de las colaterales más robustas o de la relativa resistencia de las neuronas del tronco encefálico a la isquemia, así como la mayor probabilidad de oclusiones ateroscleróticas, que puede permitir la existencia de mayores colaterales. Además, las exploraciones de imagen para identificar la penumbra en la TC no son adecuadas para evaluar el tronco encefálico y no se ha validado el uso del mismatch de imagen-clínica con la ponderación de difusión. Así pues, un estudio que incluyera tan solo a pacientes con ictus de circulación anterior podría haber sido más apropiado, aunque los resultados de este estudio no se modificaron tras la exclusión del grupo con afectación vertebrobasilar. Otra limitación de este estudio es que en la actualidad no existe un consenso respecto a lo que constituye la penumbra y qué exploración de imagen la define mejor; un análisis que incluyera los datos de resultados de pacientes no tratados a causa de la ausencia de mismatch de perfusión hubiera reforzado las conclusiones, pero no se dispone de datos al respecto. Por último, según los registros de la embolectomía mecánica que se han publicado, algunos autores pueden argumentar que una ventana temporal de 8 horas es una definición más apropiada del TIA temprano2,6. Se eligió como valor de corte para este estudio el de las 6 horas porque los resultados clínicos de los pacientes estudiados en estos registros no han sido en general buenos y por tanto no podía darse por supuesto que el TIA aplicado hasta las 8 horas fuera igual de seguro que el TIA aplicado antes de las 6 horas. Esto último ha sido respaldado también por los resultados del único ensayo aleatorizado, el Prolyse in Acute Cerebral Thromboembolism (PROACT) II, que utilizó una ventana temporal de 6 horas y en el que cabe pensar que se presentó el conjunto de datos de TIA más limpio publicado1. No obstante, al volver a analizar los datos utilizando un valor de corte de 8 horas, los resultados del estudio se mantuvieron inalterados. Resumen Este estudio mostró que el TIA multimodal puede aplicarse de forma segura en el tratamiento de pacientes que acuden después de finalizada la ventana temporal tradicional de 6 horas si se realiza una selección adecuada basada en la presencia de mismatch de perfusión. Sin embargo, serán necesarios más datos para definir mejor qué técnicas de imagen definen mejor el mismatch en la práctica clínica, y luego una validación de este enfoque en ensayos prospectivos más amplios. Agradecimientos Agradecemos la inestimable colaboración y experiencia del Equipo de Ictus: Kerri Remmel, MD, Vincent Truong, MD, Rori Spray, ARNP, CNRN, Betsy Wise, ARNP, y Craig Zeigler, PhD. Declaraciones A.A.-C. forma parte del panel de conferenciantes de BMS/Sanofi Partnership y del consejo asesor de Arterain Medical Inc. Bibliografía 1. Furlan A, Higashida R, Wechsler L, Gent M, Rowley H, Kase C, Pessin M, Ahuja A, Callahan F, Clark WM, Silver F, Rivera F. Intra-arterial prourokinase for acute ischemic stroke. The PROACT II study: a randomized controlled trial. Prolyse in Acute Cerebral Thromboembolism. JAMA. 1999;282:2003–2011. 2. Smith WS, Sung G, Saver J, Budzik R, Duckwiler G, Liebeskind DS, Lutsep HL, Rymer MM, Higashida RT, Starkman S, Gobin YP, Frei D, Grobelny T, Hellinger F, Huddle D, Kidwell C, Koroshetz W, Marks M, Nesbit G, Silverman IE. Mechanical thrombectomy for acute ischemic stroke: final results of the Multi MERCI trial. Stroke. 2008;39: 1205–1212. 3. Nakano S, Iseda T, Yoneyama T, Kawano H, Wakisaka S. Direct percutaneous transluminal angioplasty for acute middle cerebral artery trunk occlusion: an alternative option to intra-arterial thrombolysis. Stroke. 2002;33:2872–2876. 4. Dijkhuizen RM, Asahi M, Wu O, Rosen BR, Lo EH. Rapid breakdown of microvascular barriers and subsequent hemorrhagic transformation after delayed recombinant tissue plasminogen activator treatment in a rat embolic stroke model. Stroke. 2002;33:2100 –2104. 18 Stroke Abril 2011 5. Ning M, Furie KL, Koroshetz WJ, Lee H, Barron M, Lederer M, Wang X, Zhu M, Sorensen AG, Lo EH, Kelly PJ. Association between tPA therapy and raised early matrix metalloproteinase-9 in acute stroke. Neurology. 2006; 66:1550 –1555. 6. The Penumbra Pivotal Stroke Trial: safety and effectiveness of a new generation of mechanical devices for clot removal in intracranial large vessel occlusive disease. Stroke. 2009;40:2761–2768. 7. Barnwell SL, Clark WM, Nguyen TT, O’Neill OR, Wynn ML, Coull BM. Safety and efficacy of delayed intraarterial urokinase therapy with mechanical clot disruption for thromboembolic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1994;15:1817–1822. 8. Abou-Chebl A, Vora N, Yadav JS. Safety of angioplasty and stenting without thrombolysis for the treatment of early ischemic stroke. J Neuroimaging. 2009;19:139 –143. 9. The Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) trial. Phase I findings. TIMI Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:932–936. 10. Larrue V, von Kummer RR, Muller A, Bluhmki E. Risk factors for severe hemorrhagic transformation in ischemic stroke patients treated with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator: a secondary analysis of the European-Australasian Acute Stroke Study (ECASS II). Stroke. 2001;32: 438 – 441. 11. Tissue plasminogen activator for acute ischemic stroke. The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke rt-PA Stroke Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1581–1587. 12. Hacke W, Kaste M, Bluhmki E, Brozman M, Davalos A, Guidetti D, Larrue V, Lees KR, Medeghri Z, Machnig T, Schneider D, von KR, Wahlgren N, Toni D. Thrombolysis with alteplase 3 to 4.5 hours after acute ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:1317–1329. 13. Abou-Chebl A, Bajzer CT, Krieger DW, Furlan AJ, Yadav JS. Multimodal therapy for the treatment of severe ischemic stroke combining GPIIb/IIIa antagonists and angioplasty after failure of thrombolysis. Stroke. 2005;36:2286 –2288. 14. Grigoriadis S, Gomori JM, Grigoriadis N, Cohen JE. Clinically successful late recanalization of basilar artery occlusion in childhood: what are the odds? Case report and review of the literature. J Neurol Sci. 2007;260: 256 –260. 15. Wintermark M, Flanders AE, Velthuis B, Meuli R, van Leeuwen M, Goldsher D, Pineda C, Serena J, van der Schaaf I, Waaijer A, Anderson J, Nesbit G, Gabriely I, Medina V, Quiles A, Pohlman S, Quist M, Schnyder P, Bogousslavsky J, Dillon WP, Pedraza S. Perfusion-CT 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. assessment of infarct core and penumbra: receiver operating characteristic curve analysis in 130 patients suspected of acute hemispheric stroke. Stroke. 2006;37:979 –985. Gupta R, Yonas H, Gebel J, Goldstein S, Horowitz M, Grahovac SZ, Wechsler LR, Hammer MD, Uchino K, Jovin TG. Reduced pretreatment ipsilateral middle cerebral artery cerebral blood flow is predictive of symptomatic hemorrhage post-intra-arterial thrombolysis in patients with middle cerebral artery occlusion. Stroke. 2006;37:2526 –2530. Gupta R, Vora NA, Horowitz MB, Tayal AH, Hammer MD, Uchino K, Levy EI, Wechsler LR, Jovin TG. Multimodal reperfusion therapy for acute ischemic stroke: factors predicting vessel recanalization. Stroke. 2006;37:986 –990. Vora NA, Gupta R, Thomas AJ, Horowitz MB, Tayal AH, Hammer MD, Uchino K, Wechsler LR, Jovin TG. Factors predicting hemorrhagic complications after multimodal reperfusion therapy for acute ischemic stroke. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2007;28:1391–1394. Lin R, Vora N, Zaidi S, Aleu A, Jankowitz B, Thomas A, Gupta R, Horowitz M, Kim S, Reddy V, Hammer M, Uchino K, Wechsler LR, Jovin T. Mechanical approaches combined with intra-arterial pharmacological therapy are associated with higher recanalization rates than either intervention alone in revascularization of acute carotid terminus occlusion. Stroke. 2009;40:2092–2097. Lackland DT, Bachman DL, Carter TD, Barker DL, Timms S, Kohli H. The geographic variation in stroke incidence in two areas of the southeastern stroke belt: the Anderson and Pee Dee Stroke Study. Stroke. 1998;29:2061–2068. Brandt T, von Kummer R, Muller-Kuppers M, Hacke W. Thrombolytic therapy of acute basilar artery occlusion. Variables affecting recanalization and outcome. Stroke. 1996;27:875– 881. Zhang J, Yang ZJ, Klaus JA, Koehler RC, Huang J. Delayed tolerance with repetitive transient focal ischemic preconditioning in the mouse. Stroke. 2008;39:967–974. Sacco RL, Kargman DE, Gu Q, Zamanillo MC. Race– ethnicity and determinants of intracranial atherosclerotic cerebral infarction. The Northern Manhattan Stroke Study. Stroke. 1995;26:14 –20. Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, Cimminiello C, Csiba L, Kaste M, Leys D, Matias-Guiu J, Rupprecht HJ. Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, doubleblind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364:331–337. Downloadedfrom fromstroke.ahajournals.org stroke.ahajournals.orgatatWKH WKHon onFebruary February3, 3,2011 2011 Downloaded

© Copyright 2026