Controversies in Stroke

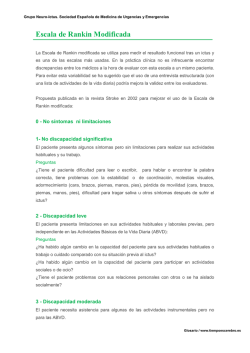

Controversies in Stroke Section Editors: Carlos A. Molina, MD, PhD, and Magdy H. Selim, MD, PhD The Case: A 61 year-old man with an asymptomatic ICA stenosis (ACS) greater than 80%. The Questions: (1) Should prophylactic carotid revascularization be considered in this patient to reduce future stroke risk? (2) Should tests like transcranial Ultrasound for microemboli detection or vascular reserve assessment be used to stratify ACS patients at high risk for stroke who would be more likely to benefit from revascularization? (3) Is revascularization more beneficial than modern best medical therapy (antiplatelets, ACE inhibitors, and statins) in this patient? The Controversy: REVASCULARIZATION OF ASYMPTOMATIC HIGH-GRADE CAROTID STENOSIS IS STILL INDICATED DESPITE CONTEMPORARY STROKE PREVENTION MEDICAL THERAPY. Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 2, 2016 Revascularization of Asymptomatic High-Grade Carotid Stenosis Is Still Indicated in Some Cases Hugh Markus, FRCP U p to 20% of ischemic stroke is caused by carotid artery disease. Robust evidence shows that operating for symptomatic carotid stenosis prevents stroke if performed early after the ischemic event, but the majority of strokes due to carotid stenosis are not preceded by minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. One approach to preventing stroke in this group of patients is to operate before symptoms occur, that is, on asymptomatic carotid stenosis (ACS). Results from 2 large well-conducted randomized controlled trials have shown that carotid endarterectomy (CEA) for ACS reduces the risk of further stroke.1,2 Despite highly significant results, the use of this preventive therapy has been questioned for 2 main reasons. First, the risk of recurrent stroke in the trials was low, as would be expected for ACS, at approximately 2% per annum. This resulted in a large number needed to treat; it was estimated that 40 operations were needed to prevent 1 disabling or fatal stroke after 5 years.3 After the trials, there was controversy as to whether this treatment benefit was worthwhile for the individual patient and also whether it was value for the money considering the many competing demands on health services. The controversy has intensified with more recent data suggesting stroke risk in medically treated patients with ACS is now significantly lower than that reported in the randomized clinical trials.4 It has been suggested that this negates any benefit of surgery or could even make surgery dangerous. Confirming this will require trials comparing CEA with current best medical therapy such as statins and rigorous control of blood pressure. Trials are currently evaluating CEA against stenting for ACS and it is important that these include a medical arm so that we can derive this information. However, such data will not be available for many years. What should the practicing clinician do in the interim? ACS presents to many different clinical specialties, including neurology and stroke, cardiology, and vascular surgery. It is important each institution has a preagreed policy. After reviewing the data in conjunction with our vascular surgeons, we concluded that operating on all ACSs was not worthwhile. However, subgroup analysis from the randomized trials has suggested there is a greater benefit in men aged ⱕ74 years.3 Therefore, in men ⬍75 years, we discuss the potential benefits and risks of operation, emphasizing that this is only 1 part of a treatment package that includes intensive treatment of cardiovascular risk factors and lifestyle modification. In our experience, approximately a half of such patients opt to proceed with CEA. In older men and women with ACS, we would suggest medical treatment alone. The reason treatment benefits are so small in ACS is because we are operating on a group of patients whose risk of stroke, if left untreated, is low. An attractive concept is to identify a subgroup who are at higher risk, who may particularly benefit from the intervention, and conversely spare those at lower stroke risk from the risks of CEA. A number of The opinions expressed in this article are not necessarily those of the editors or of the American Heart Association. This article is Part 1 in a 3-part series. Parts 2 and 3 appear on pages 1154 and 1156, respectively. Received December 30, 2010; final revision received January 21, 2011; accepted February 10, 2011. From the Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, London, UK. Correspondence to Hugh Markus, FRCP, Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, Cranmer Terrace, London SW17 0RE, UK. E-mail [email protected] (Stroke. 2011;42:1152-1153.) © 2011 American Heart Association, Inc. Stroke is available at http://stroke.ahajournals.org DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.612473 1152 Markus Revascularization of Symptomatic High-Grade Carotid Stenosis Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 2, 2016 markers of increased risk have been suggested, including the presence of CT infarction, degree of stenosis, plaque morphology on ultrasound or MRI, impaired cerebral hemodynamics, and asymptomatic embolization detected by transcranial Doppler ultrasound. Prospective studies have suggested plaque morphology and the presence of emboli are most promising.5,6 The recent Asymptomatic Carotid Emboli Study (ACES) found asymptomatic embolization, detected on either of 2 1-hour baseline recordings, was a highly significant predictor of risk over the subsequent 2 years.5 A meta-analysis of ACES with previous studies confirmed this finding.5 Transcranial Doppler ultrasound is a simple, noninvasive technique. However, there is a need for reliable automated systems, which can be easily used in clinical practice, for identification of the embolic signals; such systems have been developed for the larger emboli seen in symptomatic disease, but further work is required to confirm they can reliably identify the less intense signals seen in patients with ACS. Until these are available, it is likely to remain primarily a research technique. So what would I do in this 61-year-old man? I would explain to him the small potential benefits from CEA, counsel him about the risks, and, if he chooses to go ahead with the operation, refer him to our vascular surgeons. At the same time, I would emphasize to him the importance of lifestyle advice and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors and 1153 explain that the carotid stenosis is a reflection of a widespread disease process, which could result in stroke elsewhere in the brain and myocardial infarction. Disclosures None. References 1. Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. JAMA. 1995;273:1421–1428. 2. Halliday A, Mansfield A, Marro J, Peto C, Peto R, Potter J, Thomas D. Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1491–1502. 3. Rothwell PM, Goldstein LB. Carotid endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial. Stroke. 2004;35: 2425–2427. 4. Abbott AL. Medical (nonsurgical) intervention alone is now best for prevention of stroke associated with asymptomatic severe carotid stenosis: results of a systematic review and analysis. Stroke. 2009;40:e573– e583. 5. Markus HS, King A, Shipley M, Topakian R, Cullinane M, Reihill S, Bornstein NM, Schaafsma A. Asymptomatic embolisation for prediction of stroke in the Asymptomatic Carotid Emboli Study (ACES): a prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:663– 671. 6. Nicolaides AN, Kakkos SK, Kyriacou E, Griffin M, Sabetai M, Thomas DJ, Tegos T, Geroulakos G, Labropoulos N, Doré CJ, Morris TP, Naylor R, Abbott AL; Asymptomatic Carotid Stenosis and Risk of Stroke (ACSRS) Study Group. Asymptomatic internal carotid artery stenosis and cerebrovascular risk stratification. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:1486 –1496. KEY WORDS: asymptomatic carotid stenosis Revascularization of Asymptomatic High-Grade Carotid Stenosis Is Still Indicated in Some Cases Hugh Markus Downloaded from http://stroke.ahajournals.org/ by guest on October 2, 2016 Stroke. published online March 10, 2011; Stroke is published by the American Heart Association, 7272 Greenville Avenue, Dallas, TX 75231 Copyright © 2011 American Heart Association, Inc. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0039-2499. Online ISSN: 1524-4628 The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is located on the World Wide Web at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/early/2011/03/10/STROKEAHA.110.612473.citation Data Supplement (unedited) at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/suppl/2012/02/26/STROKEAHA.110.612473.DC1.html http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/suppl/2012/03/12/STROKEAHA.110.612473.DC2.html Permissions: Requests for permissions to reproduce figures, tables, or portions of articles originally published in Stroke can be obtained via RightsLink, a service of the Copyright Clearance Center, not the Editorial Office. Once the online version of the published article for which permission is being requested is located, click Request Permissions in the middle column of the Web page under Services. Further information about this process is available in the Permissions and Rights Question and Answer document. Reprints: Information about reprints can be found online at: http://www.lww.com/reprints Subscriptions: Information about subscribing to Stroke is online at: http://stroke.ahajournals.org//subscriptions/ Controversias en ictus Editores de la sección: Carlos A. Molina, MD, PhD, y Magdy H. Selim, MD, PhD El caso: Un varón de 61 años con una estenosis de la ACI asintomática (ECA) de más de un 80%. Las preguntas: (1) ¿Debe contemplarse una revascularización carotídea profiláctica en este paciente para reducir el riesgo futuro de ictus? (2) ¿Deben utilizarse pruebas como la ecografía transcraneal para la detección de microémbolos o la evaluación de la reserva vascular para estratificar a los pacientes con ECA de alto riesgo de ictus en los que sería más probable la obtención de un efecto beneficioso con la revascularización? (3) ¿Aporta la revascularización un efecto beneficioso superior al del mejor tratamiento médico moderno (antiagregantes plaquetarios, inhibidores de la enzima de conversión de la angiotensina y estatinas) en este paciente? La controversia: La revascularización de la estenosis carotídea de alto grado asintomática continúa estando indicada a pesar del tratamiento médico actual de prevención del ictus. La revascularización de la estenosis carotídea de alto grado asintomática continúa estando indicada en algunos casos Hugh Markus, FRCP H de los ensayos, hubo una controversia respecto a si este efecto beneficioso del tratamiento valía la pena para el paciente individual y también respecto a si su coste económico estaba justificado teniendo en cuenta las muchas demandas de servicios sanitarios con las que compite. La controversia se ha intensificado con datos más recientes que sugieren que el riesgo de ictus en los pacientes con ECA tratados médicamente es ahora significativamente inferior al descrito en los ensayos clínicos aleatorizados4. Se ha sugerido que este hecho anula todo efecto beneficioso de la cirugía o que podría hacer incluso que la cirugía fuera peligrosa. La confirmación de este extremo requerirá ensayos que comparen la EC con el mejor tratamiento médico actual, como el que incluye estatinas y un control riguroso de la presión arterial. En la actualidad se están realizando ensayos que evalúan la EC en comparación con la implantación de stents para la ECA, y es importante que estos ensayos incluyan un grupo de tratamiento médico para que podamos obtener esa información. Sin embargo, no se dispondrá de estos datos hasta dentro de muchos años. ¿Qué debe hacer el clínico mientras tanto? asta un 20% de los ictus isquémicos son causados por la arteriopatía carotídea. Existe una evidencia robusta que indica que las operaciones practicadas por una estenosis carotídea sintomática previenen el ictus si se realizan de forma temprana tras el evento isquémico, pero la mayoría de ictus debidos a estenosis carotídea no van precedidos por un ictus menor o un ataque isquémico transitorio. Un posible enfoque para la prevención del ictus en ese grupo de pacientes es el de operar antes de que se produzcan síntomas, es decir, cuando hay una estenosis carotídea asintomática (ECA). Los resultados de 2 grandes ensayos controlados, aleatorizados y adecuadamente realizados han puesto de manifiesto que la endarterectomía carotídea (EC) para la ECA reduce el riesgo de un ulterior ictus1,2. A pesar de los resultados altamente significativos, el uso de este tratamiento preventivo ha sido puesto en duda por 2 razones principales. En primer lugar, el riesgo de ictus recurrente en los ensayos fue bajo, tal como cabría prever en una ECA, de aproximadamente un 2% al año. Esto hacía que el número necesario a tratar fuera elevado; se estimó que eran necesarias 40 operaciones para prevenir 1 ictus invalidante o mortal a los 5 años3. Después Las opiniones expresadas en este artículo no son necesariamente las de los editores o las de la American Heart Association. Este artículo es la Parte 1 de una serie de 3 partes. Las partes 2 y 3 se encuentran en las páginas 1154 y 1156, respectivamente. Recibido el 30 de diciembre de 2010; revisión final recibida el 21 de enero de 2011; aceptado el 10 de febrero de 2011. Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, Londres, Reino Unido. Remitir la correspondencia a Hugh Markus, FRCP, Stroke and Dementia Research Centre, St George’s University of London, Cranmer Terrace, London SW17 0RE, Reino Unido. E-mail [email protected] (Traducido del inglés: Revascularization of Asymptomatic High-Grade Carotid Stenosis Is Still Indicated in Some Cases. Stroke, 2011;42:11521153.) © 2011 American Heart Association, Inc. Stroke está disponible en http://www.stroke.ahajournals.org 98 DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.612473 Markus La revascularización de la estenosis carotídea de alto grado asintomática 99 La ECA lleva a los pacientes a múltiples especialidades clínicas distintas, como neurología e ictus, cardiología y cirugía vascular. Es importante que cada centro disponga de una política previamente acordada. Tras revisar los datos conjuntamente con nuestros cirujanos vasculares, nosotros llegamos a la conclusión de que no era apropiado operar todas las ECA. Sin embargo, un análisis de subgrupos de los ensayos aleatorizados ha sugerido que se obtiene un efecto beneficioso superior en los varones de edad ≤ 74 años3. En consecuencia, en los varones de menos de 75 años de edad, comentamos con el paciente los posibles beneficios y riesgos de la operación, resaltando que constituye tan solo una parte de un paquete de tratamiento que incluye también un tratamiento intensivo de los factores de riesgo cardiovascular y una modificación del estilo de vida. En nuestra experiencia, aproximadamente la mitad de estos pacientes optan por que se les practique una EC. En los varones de mayor edad y en las mujeres con ECA, nosotros sugeriríamos un tratamiento médico solo. La razón de que los efectos beneficiosos del tratamiento sean tan escasos en la ECA es que estamos operando a un grupo de pacientes cuyo riesgo de ictus, si no se les trata, es bajo. Un concepto atractivo es el de identificar un subgrupo de pacientes con un riesgo superior, en los que pueda ser especialmente beneficiosa la intervención, y evitar en cambio los riesgos de la EC en los pacientes con un riesgo inferior de ictus. Se han sugerido diversos marcadores del aumento de riesgo, como la presencia de un infarto en la TC, el grado de estenosis, la morfología de la placa en la ecografía o la RM, el deterioro de la hemodinámica cerebral y la embolización asintomática detectada mediante ecografía Doppler transcraneal. Los estudios prospectivos han sugerido que la morfología de la placa y la presencia de émbolos son los factores más prometedores5,6. En el reciente estudio Asymptomatic Carotid Emboli Study (ACES) se observó que la embolización asintomática, detectada en uno de 2 registros basales de 1 hora, era un factor predictivo muy significativo del riesgo a lo largo de los 2 años posteriores5. Un metanálisis del ACES junto con otros estudios previos confirmó esta observación5. La ecografía Doppler transcraneal es una técnica sencilla y no invasiva. Sin embargo, serán necesarios sistemas automáticos fiables que puedan utilizarse con facilidad en la práctica clínica para la identificación de las señales embólicas; se han desarrollado sistemas de este tipo para los émbolos de mayor tamaño que se observan en la enfermedad sintomática, pero serán precisos nuevos estudios para confirmar que permiten identificar de manera fiable las señales menos intensas que se observan en los pacientes con ECA. Mientras no se disponga de ellos, es probable que esta exploración continúe siendo básicamente una técnica de investigación. Así pues, ¿qué conviene hacer en este varón de 61 años? Yo le explicaría los posibles efectos beneficiosos pequeños de una EC, le asesoraría sobre los riesgos y, si opta por la operación, la remitiría a nuestros cirujanos vasculares. Al mismo tiempo, le haría notar la importancia de las recomendaciones sobre el estilo de vida y el tratamiento de los factores de riesgo cardiovascular y le explicaría que la estenosis carotídea es un reflejo de un proceso patológico generalizado que podría causar un ictus en otro lugar del cerebro o un infarto de miocardio. Declaraciones de conflictos de intereses Ninguna. Bibliografía 1. Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. JAMA. 1995;273:1421–1428. 2. Halliday A, Mansfield A, Marro J, Peto C, Peto R, Potter J, Thomas D. Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363:1491–1502. 3. Rothwell PM, Goldstein LB. Carotid endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid stenosis. Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial. Stroke. 2004;35: 2425–2427. 4. Abbott AL. Medical (nonsurgical) intervention alone is now best for prevention of stroke associated with asymptomatic severe carotid stenosis: results of a systematic review and analysis. Stroke. 2009;40:e573– e583. 5. Markus HS, King A, Shipley M, Topakian R, Cullinane M, Reihill S, Bornstein NM, Schaafsma A. Asymptomatic embolisation for prediction of stroke in the Asymptomatic Carotid Emboli Study (ACES): a prospective observational study. Lancet Neurol. 2010;9:663– 671. 6. Nicolaides AN, Kakkos SK, Kyriacou E, Griffin M, Sabetai M, Thomas DJ, Tegos T, Geroulakos G, Labropoulos N, Doré CJ, Morris TP, Naylor R, Abbott AL; Asymptomatic Carotid Stenosis and Risk of Stroke (ACSRS) Study Group. Asymptomatic internal carotid artery stenosis and cerebrovascular risk stratification. J Vasc Surg. 2010;52:1486 –1496. Palabras Clave: asymptomatic carotid stenosis

© Copyright 2026