High Level Expert Group Report: FP7 Ex‐Post‐Evaluation

COMMITMENT and COHERENCE Ex‐Post‐Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme (2007‐2013) Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 1

COMMITMENT and COHERENCE

essential ingredients for success in science and innovation Ex‐Post‐Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme (2007‐2013) Chair: Rapporteur: Assistant: Louise O. Fresco André Martinuzzi Adele Wiman Members of the High Level Expert Group: Louise O. Fresco (The Netherlands) ‐ Chair André Martinuzzi (Austria) ‐ Rapporteur Maria Anvret (Sweden) María Bustelo (Spain) Eugenijus Butkus (Lithuania) Michel Cosnard (France) Arvid Hallen (Norway) Yuko Harayama (Japan) Sabine Herlitschka (Austria) Stefan Kuhlmann (Germany) Vesselina Nedeltcheva (Bulgaria) Richard Fowler Pelly (United Kingdom) picture © Marco2811 (Fotolia) Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 2

Content 1. Executive Summary ..................................................................................................... 4 2. Background and introduction .................................................................................... 12 3. Design, implementation and outcomes of FP7 .......................................................... 14 3.1. Aims and objectives of FP7 .......................................................................................... 14 3.2. Continuity between FP6 and FP7 ................................................................................. 16 3.3. Budget allocation in FP7 ............................................................................................... 18 3.4. FP7‐COOPERATION – stimulating EU wide collaborative research ............................. 19 3.5. FP7‐IDEAS – fostering EU wide research excellence .................................................... 20 3.6. FP7‐PEOPLE – building human resources, mobility and networks .............................. 21 3.7. FP7‐CAPACITIES – addressing specific needs in the innovation systems .................... 22 3.8. Agenda setting in FP7 ................................................................................................... 23 3.9. Success rates and success factors of FP7 proposals .................................................... 24 3.10. Organizations participating in FP7 ............................................................................... 26 3.11. Country participation in FP7 ........................................................................................ 32 3.12. Monitoring and evaluation of FP7 ............................................................................... 38 4. FP7 impacts on European excellence in science ......................................................... 40 4.1. Scientific excellence as a key concept of FP7 ............................................................... 40 4.2. Scientific output and impact ........................................................................................ 41 4.3. Cases of outstanding scientific achievement ............................................................... 42 4.4. European excellence on a global scale and the role of FP7 ......................................... 44 5. FP7 impacts on European research and innovation systems ...................................... 47 5.1. Contribution of FP7 to foster collaboration in research and innovation ..................... 48 5.2. Contribution of FP7 to strengthen research capability and capacity .......................... 50 5.3. Contribution of FP7 to mobility of researchers ........................................................... 51 5.4. Contribution of FP7 to international collaboration (with ‘Third Countries’) ............... 54 5.5. Contribution of FP7 to ERA and impacts on national innovation systems .................. 56 5.6. FP7 impacts on policy coherence ................................................................................. 57 6. FP7 impacts on value creation and economic growth ................................................ 59 6.1. Estimation of macro‐economic effects, growth and jobs ............................................ 59 6.2. Market impacts through successful implementation of outcomes ............................. 60 6.3. Effects on European Competitiveness ......................................................................... 61 6.4. Supporting European Industrial Base and Competitiveness ........................................ 63 6.5. Impact on the competitiveness of European SMEs ..................................................... 65 Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 7. 3

FP7 impacts on citizens and society ........................................................................... 66 7.1. The roles of citizens and civil society in FP7 ................................................................ 66 7.2. FP7 impacts on gender issues ...................................................................................... 70 7.3. Wider societal impacts of FP7 ...................................................................................... 73 8. Looking back and looking foreward ........................................................................... 76 8.1. Follow up on the FP7 mid‐term evaluation ................................................................. 76 8.2. Outlook to HORIZON 2020 ........................................................................................... 80 9. Annex ........................................................................................................................ 85 9.1. Profiles and CVs of the members of High Level Expert Group ..................................... 85 9.2. Data sources processed in preparing this report ......................................................... 88 9.3. List of references .......................................................................................................... 95 9.4. Experts consulted in preparation of this report ........................................................... 97 9.5. Abbreviations ............................................................................................................... 99 9.6. Twelve myths about FP7 ............................................................................................ 101 9.7. Institutional setting of FP7 ......................................................................................... 103 9.8. Who benefited from FP7 (by type of organization) ................................................... 105 9.9. Success rates and success factors of FP7 sub‐programmes ...................................... 107 9.10. Gender analyses ......................................................................................................... 114 9.11. Mobility of researchers in FP7‐PEOPLE ...................................................................... 119 9.12. International collaboration with ‘Third Countries’ in FP7 ......................................... 120 9.13. Annual Budget of FP6, FP7 and HORIZON 2020 by sub‐programmes ....................... 121 Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 1.

4

Executive Summary

The 7th EU Framework Programme (FP7) was one of the largest RTD programmes in the world. It accounts for the third largest share of the European Union (EU) budget and was the main financial instrument to build the European Research Area. FP7 was thus a major investment in knowledge, innovation and human capital in order to increase the potential for economic growth and to strengthen European competitiveness. This strong commitment to a European added value in research and innovation helped to build up excellent research networks, achieving outcomes faster and addressing problems from a range of perspectives, disciplines and research cultures. It is widely accepted in the business, science and education communities that, without this commitment, Europe would run the risk of losing a lot of excellent science and undermine its competitive position in innovation. It is widely accepted that a strong commitment to financing research and innovation as a long‐term investment is an indispensable condition for success and that coherence is a prerequisite for the design and implementation of effective and efficient policies and programmes. FP7 covered different themes and disciplines, addressed different stages of research and innovation chains and involved a broad diversity of stakeholders and societal groups. Given this broad scope, coherence within the programme and among its components was key. Furthermore, coherence with other policies and programmes at an EU‐level (e.g. the structural funds, growth and competitiveness policies) and at Member State level (e.g. national science and innovation programmes) is necessary to establish effective policy mixes. Following the principles of good governance regular evaluations play an important role in assessing coherence and ensuring that high impacts of publicly funded programmes materialise. The European Parliament Decision and European Council decision setting up FP7 stipulated that two years after the completion of FP7 the Commission shall carry out an external evaluation by independent experts of FP7 rationale, implementation and achievements. This report presents the findings of this ex‐post evaluation as well as recommendations for the next Framework Programme (HORIZON 2020) and RTD policies and programmes at the European and national level more generally. It informs the European Parliament, the Council, Member States, the Directorate General (DG) for Research and Innovation and various other DGs, the research community and the general public about the achievements of FP7 and challenges ahead. It aims to contribute to the continuous improvement of the design and implementation of the European Framework Programmes in general and HORIZON 2020 in particular. In contrast to the interim evaluation of FP7, this report puts a special emphasis on the impacts of FP7 on scientific excellence, economic growth, jobs and competitiveness, on the European innovation system and society at large. The findings and conclusions presented in this report are based on a range of sources of evidence. These include the programme structure of FP7, the EC budget allocations to different types of organisations and different regions, the success rates of proposals and the collaboration networks established by FP7 evaluated on the basis of CORDIS data (the Community Research and Development Information System) and partly confidential data provided by DG R&I (e.g. proposal data). Another important source was the 120+ reports of evaluation studies that were contracted by DG R&I and carried out by a number of professional evaluators and experts. For the first time, these evaluation reports were assembled in a structured repository that enabled synthesis of the evaluation findings from different sources. In addition, more than 50 experts from the EU Member States, the European Commission, umbrella organisations and national contact points were consulted. Last but not least, this report builds on the knowledge, experiences and expertise of the members of this High Level Expert Group. It also draws on the findings and recommendations of the FP7 mid‐term evaluation and addresses several new issues from an ex‐post perspective. Some impacts can already be assessed using quantitative data while many others can only be evaluated from a qualitative perspective or haven’t yet fully materialised to the extent that this evaluation could provide final conclusions. In these latter two cases a triangulation of different sources was used to provide an indication of trends and future pathways. After presenting the facts, figures and main achievements of FP7, this executive summary highlights the five key recommendations of the High Level Expert Group. More in‐depth analyses and elaborations on the recommendations can be found in the full version of this report. Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 5

FP7 at a glance

FP7 was longer and larger than previous Framework Programmes. It represented a total voted budget of 55 billion euro, which accounts for an estimated 3% of total RTD expenditure in Europe or 25% of competitive funding. Consequently, it offered more stable and predictable funding opportunities for research and innovation on a European level than ever before. Over the seven years duration of FP7, more than 139.000 research proposals were submitted, out of which 25.000 projects of highest quality were selected and received funding. The most important groups among the 29.000 organizations participating in FP7 were universities (44% of the FP7 funding), research and technology organizations (27%), large private companies (11%) and SMEs (13%), while the public sector (3%) and civil society organizations (2%) played a minor role. FP7 was built on a vast experience of designing and implementing pan‐European research and innovation programmes and managed to balance continuity and adaptability. Similar to its predecessors, FP7 aimed to strengthen the European Research Area by co‐funding RTD projects with an explicit European added value; improving researchers' qualifications and supporting their careers by promoting their mobility; stimulating competitiveness and growth through joint initiatives of research organisations and the private and the public sector; and delivering positive societal impacts in a broad diversity of themes. At the same time a number of new features were implemented in FP7. For instance, academic research was reinforced by establishing the FP7‐IDEAS programme (ERC) that supported individual top‐level researchers from every scientific discipline carrying out excellent frontier research; and the needs of industry were addressed specifically by the Joint Technology Initiatives (JTI) that built on the preparatory work of the European Technology Platforms and allowed easier and more effective collaboration. From a participant's or applicant's perspective, FP7 was an open system that allowed more than 21.000 organisations, which had not participated in the previous FP6, to receive EU funding for RTD. At the same time, concentration effects in the RTD centres of Europe occurred, as is illustrated by the fact that the Top‐500 organisations in FP7 obtained 60% of the total EC contributions. The EU Member State participation patterns reflect the size, diversity and maturity of national science and innovation systems: high shares of EU funding are allocated to large, research intensive countries like France, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. These countries often host centres of excellence that have made substantial investments in acquiring and maintaining top‐level qualified human resources and professional support structures. In contrast, Mediterranean countries that suffer from the economic crisis and high unemployment rates reduced their public RTD expenditures. While FP7 could not compensate this loss, it still provided opportunities for researchers through mobility and cooperative projects. The share of FP7 funding for organizations from new EU Member States, as well as the success rates of proposals coordinated by researchers from these countries, were significantly lower. These lower shares were not caused by a bias against the new EU Member States, but rather by a comparably high number of weak proposals submitted by, or with partners from the EU‐13. However, since the science and innovation funds on national level are also substantially lower in these countries, FP7 played a more important role in relative terms, especially in competitive funding. Given the fact that FP7 only accounts for a small proportion of total RTD expenditure in Europe, its economic impacts are quite substantial. Through short‐term leverage effects and long‐term multiplier effects each euro spent by the European Commission on FP7 generated approximately 11 euro of estimated direct and indirect economic effects through innovations, new technologies and products. In total, the indirect economic effects of FP7 can be estimated at aprproximately 500 billion euro over a period of 25 years, giving an additional annual European GDP of 20 billion euro. When translating these economic impacts into effects on employment, FP7 directly created 1,3 million person‐years within the projects funded (over a period of ten years) and indirectly 4 million person‐years over a period of 25 years. There is also evidence of positive impacts in terms of micro‐economic effects with participating enterprises reporting innovative product developments, increased turnover, improved productivity and competitiveness. However, it is still too early to make a final assessment of the market impact of FP7 projects. Beyond economic effects and job creation, a number of qualitative impacts were also achieved by FP7. Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 6

Main achievements

The key achievements of FP7, detailed below, are mirrored in quantitative data processed for preparing this report, while others are of qualitative nature and are based on the judgements of the expert panel and a number of additional experts. Areas of concern remain and are referred to in the conclusions and recommendations section as well as throughout the report in blue shaded sections. 1. Encouraged scientific excellence on individual and institutional level. FP7‐IDEAS demonstrated its ability to attract excellent researchers and become a benchmark of individual excellence. FP7‐PEOPLE has set a European standard for doctoral training of a new generation of excellent scientists. FP7‐COOPERATION facilitated transnational collaboration and thus provided a platform for the best minds to work together in order to contribute to solving major societal challenges. FP7‐CAPACITIES supported the involvement of excellent organizations from the SME sector, civil society, new EU Member States and developing countries in European research. 2. Promoted ground‐breaking research through a novel programme FP7‐IDEAS (ERC). The focus on supporting frontier research which, by definition, can be a risky endeavour, was enhanced. The number of publications in top rated scientific journals that acknowledge ERC funding, Nobel Prizes and Fields medals received by ERC grantees all attest to ERC grants becoming a mark of scientific excellence. 3. Engaged industry and SMEs strategically. Both, large corporations and SMEs have been involved extensively through increased public‐private‐partnerships, in particular the development of JTIs, and through a range of SME specific programmes. This has underlined FP7’s intended role of fostering Europe’s innovation‐based competitiveness. 4. Reinforced a new mode of collaboration and an open innovation framework. This was achieved through a more decentralized approach to the design, structure and direction of projects across the ERC, JTIs and the EIT. During the FP7 period, the European Commission has adapted the programme to the economic crisis and has responded to the a more generalised pursuit of open innovation. 5. Strengthened the European Research Area by catalysing a culture of cooperation and constructing comprehensive networks fit to address thematic challenges. A unique capability of cross‐border and cross‐sector cooperation was promoted,with organisations from on average of 6 countries collaborating in projects funded by FP7‐COOPERATION and FP7‐CAPACITIES. 6. Addressed certain societal challenges through research, technology and innovation. FP7‐COOPERATION included society‐relevant themes, such as Health, Energy, Transport and Security, whilst FP7‐CAPACITIES included a specific sub‐programme that was dedicated to "Science in Society". Furthermore, the focus on gender equality evolved from exclusively promoting individual female scientists to facilitating structural change in institutions. 7.

8.

9.

Encouraged harmonisation of national research and innovation systems and policies. In most EU Member States FP7 contributed to scientific excellence, focused on adressing societal challenges, and set standards for research funding mechanisms and selection processes. Through the sub‐programme FP7‐

ERA‐NET the cooperation and coordination of research activities carried out at national or regional level in the Member States and Associated States were intensified through networking of research activities, and the efforts to coordinate research programmes. Stimulated mobility of researchers across Europe. FP7‐PEOPLE has created the necessary conditions for an open labour market of researchers and supported their geographical mobility. Achievements during the FP7 period included fellowships gaining recognition as the best practice of doctoral training and the creation of attractive working conditions for geographically mobile researchers. Promoted investment in European research infrastructures. A combination of the support for the European Strategy Forum Initiatives for Research Infrastructures (ESFRI) and FP7‐CAPACITIES helped to achieve a more coherent and coordinated development and use of European research infrastructures. 10. Reached a critical mass of research across the European landscape and worldwide. Human and financial resources were made available to attract many organizations and individuals to collaborate with or work at European research institutions. Furthermore, a research programme of such scale has helped to put research on the public agenda and to show that research can be an instrument for economic and social development. Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 7

Conclusions and recommendations

The ex‐post evaluation of FP7 makes the following recommendations to strengthen Europe’s position as a hub of global innovation and knowledge generation: (a)

(b)

(c)

(d)

(e)

Ensure focus on critical challenges and opportunities in the global context Align research and innovation instruments and agendas in Europe Integrate the key components of the Framework Programmes more effectively Bring science closer to the European people Establish strategic programme monitoring and evaluation More detailed suggestions are provided throughout the report in blue shaded sections. (a)

Ensure focus on critical challenges and opportunities in the global context Rationale: Stimulate economic growth and jobs in a future‐oriented dynamic European knowledge and innovation based economy. Background and analysis: FP7 has been the largest cooperative research and innovation programme world‐

wide, both in size and ambition. At the same time, FP7 funded research and innovation activities have been undertaken in an environment of “coopetition” (requiring the balancing of cooperation and competition imperatives). For HORIZON 2020 and its successor programmes it will be important to “think big” in focussing on the strategically important and critical challenges and opportunities of our times, while at the same time reinforcing the need for cooperation and recognising that global competition in key areas is getting fiercer. Developing the European model of a future‐oriented knowledge and innovation based economy requires Europe, by means of its respective programmes, to focus on a number of key strategic areas, as well as ensure lean and fast implementation procedures, that reflect the dynamics in key areas of global coopetition. Implementation: In order to reflect critical challenges and opportunities of our time, HORIZON 2020 and its successors should address overarching topics that help to further develop Europe’s profile as a dynamic and future‐oriented knowledge and innovation based economy in a global context more strategically. Future economic growth, jobs and social development in Europe depend on its leading competitive position in science and technologies and the effective exploitation of these discoveries. Excellent research, a vibrant innovation value chain and disruptive innovations open up fundamentally new paths of technological and product development. The main challenges for the years ahead are to identify a number of key areas in which Europe can play a truly leading role on a global scale, to ensure that the sources of this competitive advantage are strategically built up and developed, and to increase Europe's attractiveness for leading researchers and innovators in these areas. Europe should make the most of its immense potential by continuing to bring into science and innovation the different key actors in order to get the best value from the available talent, including women. The engagement of the private sector through large industrial players is critical to the success of an EU Research and Innovation programme. The EC should therefore establish a permanent mechanism of dialogue with the private sector, commit to continuous improvement during the lifetime of HORIZON 2020 and develop a strong European Innovation Strategy. In particular, the instrument of JTIs should be further strengthened and the contractual framework should be simplified. Improvements are required to ensure that SMEs play an increasingly important role in the innovation value chain. In addition to existing initiatives, the EC should encourage SME participation in national programmes as they are typically more appropriate to the needs of SMEs, as well as develop a range of indicators at European level to unlock the full potential of SMEs. Europe should build on research and innovation in a more targeted way to address the critical challenges and involve the civil society more broadly to build a socially, economically and environmentally sustainable future. Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme (b)

8

Align research and innovation instruments and agendas in Europe Rationale: Increase synergies, effectiveness and efficacy of the European Science, Technology and Innovation System. Background and analysis: FP7 accounted for a small share of RTD investment and human resources in research in Europe. In order to achieve maximum effects with this given budget the Framework Programmes should not be perceived as an independent and detached funding system, but rather as a strategic intervention into the totality of research and innovation systems of the EU and its Member States. Instead of aiming at simplistic multiplier effects, the catalytic impacts of a European framework should be pursued. FP7 showed major progress in this regard: establishing the ERC was a successful intervention that increased competition, transparency and openness in European research. FP7‐PEOPLE helped to link science and industry via the European Industrial Doctorate Programme and the Industry Academia Partnership Programme. The ERA‐NET programme motivated national funding schemes to open up their programmes for applicants from other EU Member States. The FP7‐COOPERATION programme provided a reference scheme for cross‐border cooperation and introduced good management practices and impact orientation in a large number of European universities. The RSFF linked the EU Framework Programmes with funding instruments from the banking sector. At the same time, FP7 also showed some weaknesses: overall, the programme was oriented towards broad, general and rather obvious policy objectives (such as innovation, competitiveness and mobility), but lacked effective integration between them. Moreover, some of these were contradictory to a certain extent (such as project call requirements for highly efficient project structures, on the one hand, and coverage of as many EU countries as possible, on the other). Moreover, there were signs of inconsistencies, competition, lack of coherence and overlap of elements of FP7 and national programmes. This also occurred on the European level between the Framework Programmes and research and innovation efforts in other Directorates. Implementation: The Framework Programmes should combine strong policy objectives with decentralised and flexible implementation procedures. Implicit assumptions about how Framework Programmes work should be made explicit and published. Development of research themes and topics should focus on defining a number of concrete goals, while approaches and methods to accomplish these goals should be determined on a bottom‐

up basis. At the same time, it should be ensured that there is enough room for the unforeseen and social innovation, which may emerge both in fundamental and applied research.

In order to align the Framework Programmes with related policies and programmes at the European level the potential of a "Common Science, Technology and Innovation Policy" across the EU should be explored. Structural Funds should be used in a complimentary way to bring research facilities and salary levels of Eastern and Southern Europe to a competitive level; regional centres of excellence in these countries should foster specialization and provide attractive opportunities for researchers. A dedicated science, technology and innovation support fund within the Structural Funds is recommended. National and EU programmes should align their research priorities better using appropriate tools and incentives (such as pooling of funding in order to improve leverage effects, considering the innovation supply chain, shared databases and support of mobility). In a broader perspective also other policies and regulations should be more supportive towards innovation. The importance of quality standards for research is underlined. It is recommended that by establishing an EU‐wide quality stamp for outstanding scientific and enterprise driven proposals, successful proposers would be allowed to apply for funding at the national level in a streamlined manner.

(c)

Integrate the key components of the Framework Programmes more effectively Rationale: Efficiency, synergies and coherence of the Framework Programmes. Background and analysis: FP7 showed a complexity that stems from the long history of Framework Programmes and the expertise and interests of different DGs. Furthermore, special sub‐programmes (such as the SME, the International Cooperation and the Science in Society Programme in FP7‐CAPACITIES), as well as major programme parts (such as JTIs meeting the needs of industry or FP7‐IDEAS for science) were gradually introduced in response to particular needs of stakeholder groups. As a consequence, fragmentation and the Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 9

emergence of ‘silos’ have tended to threaten efficiency and coherence of the Framework Programmes in terms of compartmentalization and duplication of themes. In addition, some successful elements of FP7 were provided mainly through certain sub‐programmes, even though they would be equally useful in other sub‐

programmes. For example, mobility of researchers is promoted through FP7‐PEOPLE, but is not a key feature of FP7‐COOPERATION projects. On the other hand, some integration measures were implemented, e.g. the introduction of joint / coordinated calls and the PROOF OF CONCEPT scheme in FP7‐IDEAS, which supports ERC grant holders in generating innovative potential from their ERC‐funded project. Recent outsourcing of implementation, while needed, adds to the danger of further fragmentation as well as reduced transparency. Implementation: To increase efficiency and coherence of the Framework Programmes, synergy potentials should be assessed and implemented, while duplications between the different specific programmes and sub‐

programmes should be avoided in the future. The programme structure should allow budget transfers between programme years, particularly in those programmes that are open to all disciplines and themes, and that implement a bottom‐up approach (such as FP7‐IDEAS and FP7‐PEOPLE). Effective coordination processes between the agencies in charge of implementing HORIZON 2020 should be established to minimise fragmentation and ensure a high level of transparency. Funding instruments should be harmonised with a special emphasis on fostering linkages between the specific programmes (enabling the use of FP7‐PEOPLE funding opportunities for the preparation of FP7‐IDEAS proposals). Future Framework Programmes will benefit from making successful elements available across the programme (e.g. foster researcher exchanges in collaborative projects in addition to the Marie Curie Actions). (d)

Bring science closer to the European people Rationale: Increasing trust, acceptance, and ownership of research, and ensuring its relevance and creativity. Background and analysis: Research, industry, policy making and civil society combine essential complementary assets. In order to achieve a generally positive perception of science and better adoption of new knowledge and innovations, European research should increase citizen trust. FP7 has already addressed these challenges, but not in a substantial way. Two sub‐programmes addressed issues of high importance for citizens and society, but budgets of both were comparatively small: The Science in Society programme accounted for 0,65% of the FP7 budget, while 1,30% was allocated to the theme “Socio‐Economic Sciences and Humanities” in FP7‐

COOPERATION. Civil society organizations have been scarcely included in relevant decision‐making bodies, such as evaluation boards or expert groups. Furthermore, the gender balance and the representation of women on all levels (e.g. as grantees, leading researchers, coordinators, evaluators and experts), and the integration of gender into the research content was not substantially improved since the interim evaluation. During FP7 societal concerns regarding research and innovation (such as participation, open access, ethics) were integrated into a coherent and broadly accepted framework. Implementation: Future Framework Programmes should involve stakeholders more in building an evidence driven and science based society of the future and integrate civil society organizations in a more substantial way (for example by their inclusion in evaluation panels or by particular partnership programmes). Citizens and stakeholders should be engaged in a dialogue about the purpose and benefits of research and the way it is conducted. This entails the development of incentives for science communication as well as the establishment of particular support for more strategic measures of communication with different audiences. It should be encouraged to design projects in a way that supports the formation of linkages between researchers, citizens and policy‐makers. More tailored and targeted dissemination activities should be enforced and monitored. It is recommended to combine the current initiatives for agenda setting and stakeholder involvement in a sub‐

programme dedicated to “Visions and Agendas”. A European integrity code for scientists should foster people’s trust in science and innovation. Furthermore the dissemination of gender equality, diversity, ethics and participation should be fostered. Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 10

(e)

Establish strategic programme monitoring and evaluation Rationale: Improve governance, accountability and performance of the Framework Programmes and enable better, evidence‐based and strategic decision making and foster continuous learning. Background and analysis: Given the size of research expenditures of FP7, evidence‐based decision‐making, in combination with adequate governance and institutional learning, are indispensable in order to ensure the continuous improvement of programme design and implementation. While evaluation activities have been established as routine procedures in recent years, their management was still organised in a very fragmented fashion. There are indications that evaluations do not fulfil their potential as instruments for facilitating continuous learning processes and the development of a solid strategic intelligence. There has been hardly any consolidation, validation, comparison or synthesis of information provided by the more than 120 independent evaluations of FP7 themes and areas. While data sets for monitoring (such as OpenAIRE, PIC codes or the improved data structure of SESAM) have been improved during the running time of FP7, these data sets have hardly been used as instruments for the systematic generation of knowledge and, more importantly, strategic intelligence. Some important information was still lacking (e.g. tracing careers of researchers, dissemination activities, activities to link research and policy making). High fluctuation rates in advisory bodies further impede continuous build‐up of knowledge at the individual level. Recent outsourcing of programme implementation activities to agencies has further increased the existing demand for monitoring, governance and control. The need to ensure and improve governance and learning capacities in HORIZON 2020 calls for the development of centralised competence and capacity in DG R&I. All these measures do not only aim at safeguarding accountability, but also at fostering evidence‐based decision‐making in further improving the programme design, implementation and outcomes, as such serving as basis for strategic decision making. Implementation: Considering that the Framework Programmes have consistently been the third largest budget of the European Union, a strategic and professional monitoring and evaluation system is required that increases transparency and serves as a comprehensive and trusted source of evidence‐based decision making. Based on precisely defined targets and a sound understanding of the theory of change, certain key data sets should be developed (e.g. tracing of individual researchers, gender monitoring and proposal evaluation results). It is also recommended that evaluation purposes, criteria, questions and report formats should be harmonized. The wide range of individual evaluations should be better planned and utilized to build up a coherent knowledge base that allows for continuous improvement of the Framework Programme. More focus should be given to quality control and standardisation of data sets in contracted evaluations to ensure they can be used as the evidence base for strategic decisions. Furthermore, a rigorous approach to evaluation syntheses and meta‐evaluations will enable systematic access to findings and ensure a better quality of evaluation studies. Establishing such a monitoring and evaluation system will require additional budget allocation and investment in personnel within DG R&I, but savings can certainly be made in the overall cost of evaluations in the long run. Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 11

Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 2.

12

Background and introduction

This report fulfils the obligation set out by the legal basis of FP7 to carry out an independent external evaluation of the rationale, implementation and the achievements of the Framework Programme two years after its completion. Since the last work programme of FP7 was implemented in 2013, the High Level Expert Group for the ex‐post evaluation of FP7 was set up in November 2014 and tasked with carrying out this evaluation. The group is comprised of 12 members, including a Chair and Rapporteur (for the full list and member’s profiles please see Annex 9.1.). The High Level Expert Group has drafted this report as a collective endeavour based on available and collected evidence (for a full list of data sources please see Annex 9.2.), hearings of internal and external experts (for full list of experts consulted in the preparation of this report please see Annex 9.4.) and the expertise and judgements of the members of the group. The objective of this report is to evaluate the implementation and effectiveness of FP7 and to summarize what FP7 has achieved and what shortcomings in its design and implementation could be identified. It aims to provide key insights that will help guide the future design of European Research Framework Programmes as well as Science, Technology and Innovation (STI) policies on the EU and national levels. The point of reference for this evaluation is the aims and objectives of FP7 as set out at the time of its adoption, wider EU policy goals regarding the European Research Area and the Europe 2020 Strategy. Consideration has also been given to the wider scientific, economic and societal impacts of FP7. It provides evidence‐based insights for the European Parliament and the Council, the European Commission and supports EU Member States, the research community, the general public, the media, civil society organisations and European industry, among other stakeholders, in the debate about the future of European research and innovation policy and the role of science and innovation as a stimulus for growth and global competitiveness. Although this report is an ex‐post evaluation, it is future looking and provides specific recommendations for more appropriate and effective implementation of future European Framework Programmes. Where appropriate, comparisons with the previous FP6 are made to illustrate trends. Certain aspects have been deliberately excluded from the scope of this report. The report does not assess the budget shares between different sub‐programmes, themes or areas, nor does it discuss the options for a completely different usage of the FP7 budget. It makes recommendations for further implementation of HORIZON 2020 and subsequent programmes but does not discuss details of HORIZON 2020 and its implementation (this will be the core of the mid‐term evaluation of HORZION 2020). It addresses FP7 as an STI programme and not the institutions that stand behind its design and implementation (e.g. DG R&I as the coordinating organisation or the implementing agencies). In contrast to many other evaluations, this report focuses on questions related to whether FP7 has been successful in achieving its aims and is thus not structured according to the specific programmes of FP7. Rather, it is structured according to key evaluation aspects such as the appropriateness of the programme design, implementation and programme; and the evidence of outcomes and impacts. The report contains 6 sections that are each dedicated to one of the key evaluation aspects. Each chapter discusses the rationale and objectives that are set in FP7, presents and discusses evidence and ends with conclusions and recommendations (highlighted in blue boxes). The Annex provides in‐depth information on a number of selected issues which are summarized in the following chapters. Chapter 3 focuses on the design, implementation and outcomes of FP7. It starts by summarizing and discussing the overarching goals and rationale of FP7 as a programme and then presents a comparison between FP6 and FP7 in more detail and an overview of thematic continuity all the way from FP3 to HORIZON 2020. Chapter 3 continues by analysing the main output of FP7 in terms of total budgets allocated, number of projects funded, number of participants who received funding and average EC contributions across FP7‐COOPERATION, FP7‐IDEAS, FP7‐PEOPLE and FP7‐

CAPACITIES. Further on, a number of programme design aspects are discussed, including the agenda setting process in FP7, eligibility, funding schemes and rates, project evaluation procedures. The chapter explores more deeply the success rates of participating organisations across four specific Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 13

programmes and offers an analysis of data on the different types of organisations that participated in FP7, how many of them where newcomers compared to FP6 and from which countries participants came. The degree of concentration of participating organisations and the analysis of the FP7 monitoring and evaluation system are discussed as well as the participation of new EU Member States in FP7. The chapter ends with a discussion on the monitoring and evaluation system and the overall design of the FP7 as a programme. Chapter 4 analyses the contribution of FP7 to fostering excellence in European science in terms of publication output, patent applications and other indicators of high scientific excellence in FP7 funded projects. Cases of outstanding scientific achievement are highlighted. The role of each of the specific programmes in promoting excellence is discussed. Chapter 5 offers insights in response to the question as to what extent FP7 has contributed to strengthening European research and innovation systems. The importance of fostering collaboration across national and institutional borders as well as the role of FP7 in strengthening European research capacities is discussed. The structuring effects and impacts of FP7 on national research systems across the EU and impacts on fostering research policy coherence are explored. The chapter ends with an analysis of FP7 outputs in terms of fostering international collaboration with countries outside the EU in pursuit of scientific excellence and economic competitiveness and an analysis of the impacts of FP7 on researchers’ mobility. Chapter 6 investigates the impacts of FP7 on value creation and economic growth in the EU. The chapter offers an estimation of GDP and job effects and examples of innovations significant for European competitiveness. Broader effects on progress in innovation and competitiveness indicators such as patents, innovation scorecards are presented. Apart from indicators, Chapter 6 presents an overview of the effects the innovative public‐private‐partnerships are having on the European industrial base. Lastly the role and impacts on European SMEs are presented. Chapter 7 captures the effects of FP7 on citizens and society. The relevance of FP7 for citizens and society in different roles are foremost discussed, leading to a discussion on the role of society in research including responsible research and innovation and focusing FP7 funded research on society‐related issues. Furthermore, the extent to which responsible research and innovation has gained traction in FP7 is addressed. FP7 impacts on gender equality and wider societal impacts in terms of addressing sustainable development in FP7 are evaluated. Chapter 8 looks back to the FP7 interim evaluation and to what extent the issues highlighted at the mid‐point of FP7 have been addressed in FP7 and later in HORIZON 2020. The chapter concludes by drawing special attention to the recommendations of this report that are the most relevant to be addressed by HORIZON 2020 in order to achieve the goals the FP7 successor European Research Framework Programme has set and to avoid the shortcomings that have limited FP7’s success. Several Annexes are made available at the end offering a deeper analysis of issues covered including extensive data tables, a map of the institutional setting for FP7 as well as debunking twelve widespread myths about FP7. Throughout this report comma (",") is used as decimal mark and point (“.”) as thousands separator. Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 3.

FP7 Design, implementation and outcomes

3.1.

Aims and objectives of FP7

14

Research and innovation processes are characterized by complex interactions, feed‐back loops and variable. The 7th Framework Programme was the largest consolidated effort and investment in European research and innovation. Its overriding aim, as set out in the European Parliament Decision No 1982/2006/EC1, was to “contribute to the Union becoming the world’s leading research area”. FP7 has also been tasked “to strengthen industrial competitiveness and to meet the research needs of other Community policies”. In achieving this aim, the programme has focused “on promoting and investing in world class state‐of‐the‐art research, based primarily upon the principle of excellence in research”. Moreover, the legal basis of FP7 has set out that by investing in a “more stable foundation” for the European Research Area (ERA) a positive contribution to “the social, cultural and economic progress of all Member States” is expected. The role of research in promoting the strategic goal of the European Union to “become the most competitive and dynamic knowledge – based economy in the world, capable of sustainable economic growth with more and better jobs and greater social cohesion” has been acknowledged by the Lisbon Council and further reinstated by the European Council and the European Parliament (Resolution of 10 March 2005 on science and technology — Guidelines for future European Union policy to support research2). Thus, the following objectives of FP7 can be derived: 1. Promoting excellence in research 2. Fostering competitiveness and economic growth 3. Contributing to solving social challenges 4. Strengthening the human potential and researchers’ mobility 5. Fostering transnational research cooperation Research excellence has become an even greater focus in the 7th Framework Programme. The importance of promoting transnational cooperation and strengthening of human potential has remained as the continuous pillar from previous framework programmes and is central to the three key objectives of FP7. However, the 7th Framework Programme expanded on these key objectives by highlighting the need to enhance “the dynamism, creativity and excellence of European research at the frontier of knowledge” – the objective that underlines the new specific programme FP7‐IDEAS. The focus on competitiveness has also been strengthened in FP7. The economic crisis has dictated an even stronger move towards improving research performance in the pursuit of achieving the goals of the Europe 2020 Agenda. In search of new sources to fuel the European economy, the flagship initiative the “Innovation Union” was announced in 2011. Since Europe was lagging behind in R&D spending compared to its global competitors, such as the US and Japan, the Innovation Union called for more investment into strengthening the European knowledge base. The initiative aimed to improve “access to finance for research and innovation” and to “ensure that innovative ideas can be turned into products and services that create growth and jobs”3. As a result, FP7 shifted its focus even more to innovation as a means of fostering European global competitiveness mid‐programme. Supporting science as a means to reach European policy objectives related to societal wellbeing inherent in FP7 is not a new phenomenon compared to previous Framework programmes. However, FP7 marked a milestone by setting explicit expectations for science to contribute to solving some of the pressing challenges 1 European Parliament (2006) Decision No 1982/2006/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 concerning the Seventh Framework Programme of the European Community for research, technological development and demonstration activities (2007‐2013) 2 European Parliament (2004), European Parliament resolution on science and technology “Guidelines for future European Union policy to support research” (2004/2150(INI)) 3 European Commission (2010) Communication from the Commission on Europe 2020 Flagship Innitiative Innovation Union. SEC(2010) 1161. Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 15

the EU faces today. The objectives of FP7 clearly stated its aim to contribute to finding solutions to “climate change and sustainability, the health of Europe’s population and the reinvigoration of the Lisbon strategy”. Strengthening the human potential and researchers’ mobility has been a continuous objective rooted in FP4. Top quality researchers are seen as both key to knowledge production and innovation in the EU, as well as fundamental to creating the ERA. Thus, promoting their mobility and network building is an important imperative. Fostering transnational research cooperation has underpinned FPs since their inception. Trans‐European and global cooperation in research is key to the knowledge exchange needed to solve the most complex of scientific challenges and to create European added value. Despite these far reaching goals, FP7 stressed its complementary role to EU Member States’ and European Industry’s efforts and other Community actions in support of the goals of the Union. It has thus not been the sole instrument of advancing European competitiveness and solving societal challenges. Yet, its role has been pivotal in supporting research that contributes to these aims. FP7, as well as predecessor FPs, is also a result of multi‐annual political negotiations. As such, a programme of this size navigates complex and often competing objectives. FPs in Europe are set to contribute to long term objectives, which cannot be reached within the time frame of one FP. Continuity and change are observed throughout the evolution from one FP to the next (for a discussion of continuity between FP6 and FP7 see Chapter 3.2.). Furthermore, the FPs had to adapt to changes in global society and economy – in the case of FP7 especially in the aftermath of the 2008 economic crisis. Thus, FPs have had to balance between continuity of long term objectives and adaptability to emerging global and local challenges. These evolutionary effects have to be considered and FP7 has to be assessed against the backdrop of the complexity and dynamism of the system which it aims to steer. FP7 has proven to be flexible enough to adapt to the changing environment caused by the financial and economic crisis. This need to adapt was possible to accommodate due to rather general commonly agreed aims. On the other hand, imprecise aims run the risk of not being attained, when they are not operationalized through concrete targets. Furthermore, several more concrete aims (such as contributing to European cohesion, promoting gender equality or supporting sustainable development) were set, without considering potential contradictions with the five explicitly stated broad aims of the programme. To avoid these constraints, HORIZON 2020 and its successor programmes should “think big” and focus on strategically important and critical challenges and opportunities. Programme aims should be made as specific as possible, concrete targets should be set and the coherence of the different explicit and implicit aims should be ensured. Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 3.2.

16

Continuity between FP6 and FP7

FP7 was launched in a very different socio‐economic landscape than FP6 in 2005. The Lisbon strategy faced a mid‐term review resulting in the conclusion that most initial goals were not achieved. As a result, the strategy was refocused to promote growth and jobs in parallel to promoting sustainable development. At the same time, the end of FP6 marked the end of the largest process for the enlargement of the European Union to date, with 13 new Member States joining during the 2004 and 2007 enlargements. The changing policy environment was mirrored in the differences between FP6 and FP7 in terms of focus, structure and specific instruments. FP7 broadened the thematic focus compared to FP6. The largest part of FP7 was constituted by the specific programme FP7‐COOPERATION, which was structured around 10 priority themes that saw new themes emerging (e.g. Security), but also exhibited continuity with the themes in FP6. FP7 also demonstrated a stronger orientation towards the notion that research serves wider policy goals in comparison to FP6 in both the choice of thematic priorities and the introduction of new “impact statements” in project proposals. FP6 was much more focused on promoting scientific and technological advancement, strengthening and structuring of the ERA and promoting international cooperation. FP7 also marked a change in the structure of the programme. FP6 was primarily structured around three “instruments“: (1) focusing and integrating European research (including thematic priorities and specific activities targeted at policy support, SME involvement and international cooperation); (2) structuring the ERA (incl. stimulating innovation, transfer of knowledge, developing human resources, research infrastructures and science and society); and (3) strengthening the foundations of the ERA. FP7 was structured into four main programmes which reshuffled and incorporated specific parts of FP6. Promoting international cooperation was streamlined into FP7‐COOPERATION within ten specific thematic priorities. Developing human potential and strengthening research infrastructure, grouped together in FP6, were divided into two separate programmes in FP7 – FP7‐PEOPLE and FP7‐CAPACITIES respectively. The efforts in the ‘Science and Society’ stream were scaled up and continued in FP7 as the FP7‐CAPACITIES themes ‘Research Infrastructures’ and ‘Science in Society’. One of the most novel additions to FP7 was the FP7‐IDEAS programme aimed at exploratory, ambitious frontier research overseen by the European Research Council (ERC). Its predecessor in FP6 could be regarded as the “New and Emerging fields in Science and Technology” (NEST) programme, which relied on researchers to propose projects that could set new directions, in order to promote cutting edge research knowledge in new and interesting research avenues. In FP7, in line with a greater focus on growth, jobs and competitiveness, a new activity – the Joint Technology Initiatives (JTIs) – a form of public‐private partnerships (PPP), were established to implement a number of European Technology Platforms (ETP). These were regarded as an important mechanism to promote industrial research and foster European competitiveness and a central new component of FP7. On the administrative side the budget and the length of the programme was also increased in FP7. In the middle of the FP7 implementation period, a few measures aimed at simplifying the rules and procedures to improve programme effectiveness, attractiveness and accessibility were also introduced. FP7 thus builds on and goes beyond previous Framework Programmes. However, it did see significant changes in the more strategic structuring of the programme and better integration of wider goals (e.g. international cooperation). FP7 also broadened its thematic focus to bring research closer to the policy needs of the EU. New experimental funding modalities such as ERC and JTIs were also introduced. Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 17

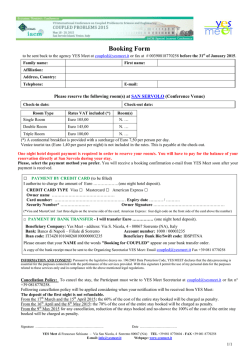

Thematic continuity between FP3 and HORIZON 2020 FP3

FP4

FP5

Information and

communication

technologies

RACE 2

Acts

ESPRIT 3

ESPRIT 4

TELEMATICS 1C

TELEMATICS 2C

FP7

H2020

Information and

communication

technologies

ICT

Security

Security

FOOD

Food, agriculture

and fisheries, biotechnology

Biotechnology

LIFESCIHEALT

Health

Health

Nanosciences, ‐

technologies, ‐

materials & new

production

techniques

Nano and new

materials

Space

Space

Transport

Transport

FP6

1. Focusing and

integrating European research

IST

IST

Life sciences and

technologies

BIOTECH 1

BIOTECH 2

BIOMED 1

BIOMED 2

AIR

FAIR

Quality of life

Industrial technologies

BRITE‐EURAM 2

BRITE‐EURAM 3

MAT

SMT

NMP

GROWTH

AEROSPACE

Transport

SUSTDEV

TRANSPORT

Food

Energy

Energy

Environment

Climate

Environment

ENV 1C

ENV 2C

MAST 2

MAST 3

Future and

emerging

technologies

EESD

NEST

ERC

FP7‐IDEAS (ERC)

Energy

JOULE 2

JOULE

Research potential of Convergence

Regions

THERMIE

Cooperations with

third countries and

international organisations

STD 3

INCO

International cooperation

CITIZENS

Socio‐economic

sciences and

humanities

SME

Research for the

benefit of SMEs

Innovation in SMEs

RSFF*

Access to risk

finance

FP7‐PEOPLE

(Marie Curie actions)

Marie Skłodowska‐Curie actions

Research infrastructures

Research infrastructures

Science in Society

Science with

and for

society

INCO 2

INCO

Targeted socio‐

economic research

IHP

SUPPORT

TSER

2. Structuring the ERA

ETAN

MOBILITY

Stimulation of training

& mobility of

resaerchers

INNOVATION

INNOVATION

INFRASTRUCTURE

HCM

TMR

SOCIETY

3. Strengthening the

foundations of the

ERA

Dissemination and

exploitation of results

POLICIES

INNOVATON

Inclusive societies

Support coherent

development of

research policies

Spreading

excellence

Regions of

knowledge

COORDINATION

RENA

Research and training

in the nuclear sector

Euratom

FUSION 11C

FUSION 12C

NFS 1

NFS 2

EURATOM

EURATOM

Coordination of

research activities

JRC

Knowledge in society**

EIT

EURATOM

EURATOM

FP7‐

COOPERATION

H2020 Societal

challenges

FP7‐CAPACITIES

H2020 Industrial leadership

H2020 Excellent

science

*RSFF: developed by the European Commission (EC) and the European Investment Bank (EIB), succeeded by H2020 specific objective “Access to Risk Finance”

Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 3.3.

18

Budget allocation in FP7

Total FP7 voted budget was over 55 billion euro4. Compared to predecessor Framework Programmes, FP7 was also substantially longer ‐ the duration of FP5 and FP6 were 4 years each, while the duration of FP7 was 7 years. FP7 also offered a 66% higher annual European Commission funding compared to FP6; FP6 funding was 4,8 billion per year while FP7 was 8 billion euro per year. 81% of the voted budget (44,6 billion euro) was allocated to four specific programmes, namely FP7‐

COOPERATION, FP7‐IDEAS, FP7‐PEOPLE and FP7‐CAPACITIES. All four specific programmes were implemented through annual Work Programmes containing a number of competitive calls for proposals. These four specific programmes are in the focus of this ex‐post evaluation. The remaining 19% of the total FP7 budget was used to cover administrative expenditures of the European Commission (EC) associated with the implementation of FP7, as well as other instruments namely the Risk Sharing Finance Facility (RSFF) (in collaboration with the European Investment Bank), the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), Nuclear Fusion and Fission Research (e.g. FP7 Specific Programme Euratom) and the Joint Research Center's (JRC) direct actions. These activities and associated costs are not within the scope of this evaluation. For the purpose of this evaluation study detailed data on FP7 research projects and participating organizations in the four specific programmes was made available by Directorate General for Research and Innovation (DG R&I), the eCORDA database. This dataset covers the following:

approx. 44,6 billion euro of EC contribution to approx. 25.000 projects involving approx. 29.000 organizations. In addition to the data from eCORDA, additional data on FP6 funded projects and participating organizations, as well as data on proposals submitted for FP7 funding, was provided by DG R&I. This data was used to analyse potential overlaps between FP6 and FP7 in terms of participating organizations and for gaining insights into the potential success factors of research proposals. FP7 was substantially longer and larger than previous FPs. It offered more stable and predictable funding opportunities for research and innovation on European level than previously available. The increase in FP funding mirrored a substantial commitment of the European Union for promoting research and innovation. Collaborative research was the key element of FP7 since approximatley half of the voted budget and 64% of the research project funding was allocated to FP7‐COOPERATION. 4 European Commission (2013), Development of Community Research – Commitments 1984‐2013. Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/research/fp7/pdf/fp‐1984‐2013_en.pdf Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 3.4.

19

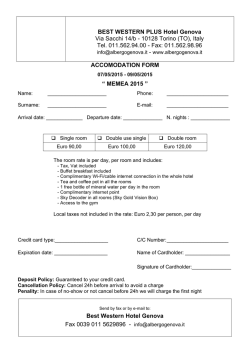

FP7-COOPERATION – stimulating EU wide collaborative research

64% of the EC contribution to research projects (approx 28 billion euro) was allocated to the specific programme FP7‐COOPERATION. In this specific progamme a total of 7.912 projects were funded. The project size ranged from 1,5 million euro to more than 50 million euro. The programme was constituted by ten thematic areas ("Themes") covering a broad variety of societal and policy relevant challenges (e.g. Health, Environment, Security) and areas in which major innovations were expected (e.g. ICT, NMP, Space). In addition, the ERA‐NET programme and the Joint Technology Initiatives (JTIs) can be subsumed into FP7‐COOPERATION (although they show different funding characteristics). The highest share of EU funding was allocated to projects in the field of ICT (18%) and Health (11%) followed by NMP (7%) and Transport (5%) themes. The average EC contribution per project in these themes lies between 3 and 5 million euro. The average EU contribution per partner organization was between 300.000 and 425.000 euro. The smallest share of the EC contribution, the lowest number of funded projects and the lowest EC contribution per project and per organization is found in theme “Social Sciences, Economics and Humanities” (for further details see Chapter 7.1.). The EC contribution to individual projects was allocated on the basis of competitive proposals addressing specific topics published in annual work programmes. In total, approx 3.200 topics were published in FP7‐

COOPERATION work programmes. Every proposed project had to clearly address one of these topics, involve partners from at least three different countries and focus on research, innovation, networking or dissemination. The thematic priorities, topic descriptions and budget allocation per topic was developed and decided upon by the European Commission in a top‐down process (for the details of the programming process see Chapter 3.8.). Submitted proposals were reviewed and awarded points by independent evaluators based on three criteria: (1) excellence; (2) implementation; and (3) potential impacts. FP7‐COOPERATION

Total EC contribution % of EC (in million contrib.

euro)

number of projects

Theme 01 ‐ Health

Theme 02 ‐ KBBE

Theme 03 ‐ ICT

Theme 04 ‐ NMP

Theme 05 ‐ Energy

Theme 06 ‐ Environment

Theme 07 ‐ Transport

Theme 08 ‐ SSH

Theme 09 ‐ Space

Theme 10 ‐ Security

ERANET

JTI

Subtotal FP7‐COOPERATION

4.792

1.851

7.877

3.239

1.707

1.719

2.284

580

713

1.295

313

1.966

28.336

1.008

516

2.328

805

368

494

719

253

267

314

104

736

7.912

11%

4%

18%

7%

4%

4%

5%

1%

2%

3%

1%

4%

64%

average EU number % of contribution of partici‐ projects

per project pations

(in 1000 euro)

4%

2%

9%

3%

1%

2%

3%

1%

1%

1%

0%

3%

31%

11.297

7.903

22.502

10.235

4.272

7.148

9.029

2.770

2.636

3.836

183

5.812

87.623

4.754

3.587

3.384

4.023

4.640

3.480

3.177

2.291

2.671

4.126

3.007

2.672

3.581

average average EU partici‐ contribution pations per per participation project (in 1000 euro)

11,21

15,32

9,67

12,71

11,61

14,47

12,56

10,95

9,87

12,22

1,76

7,90

11,07

424

234

350

316

400

241

253

209

271

338

1.709

338

323

FP7‐COOPERATION combined the objective of EU‐wide collaborative research with a logic of public procurement: major research areas and individual research topics were identified in a top‐down manner, proposals were selected by independent evaluators based on objective criteria and implemented by a large number of research and innovation projects. This collaborative approach strengthened the European Research Area by catalysing a culture of cooperation and constructing comprehensive networks fit to address thematic challenges. While a unique capability of cross‐border and cross‐sector cooperation was promoted, societal challenges were addressed such as Health, Energy, Transport and Security. Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 3.5.

20

FP7-IDEAS – fostering EU wide research excellence

The specific programme FP7‐IDEAS was newly introduced in FP7 in order to increase research excellence in Europe and Europe’s attractiveness for the world renounded researchers. The programme targeted these goals through funding investigator‐driven research that stems from researchers’ own innitiative. 17% of the total FP7 EC contribution (approx. 7,7 billion euro) was allocated to this specific programme, in which 4.525 projects were funded. In order to implement the programme the ERC (European Research Council) was established, which, through the independed Scientific Council, was tasked with establishing a peer review process for project proposals and controling scientific quality. Most of the EC contribution in FP7‐IDEAS was allocated to two sub‐programmes with rather similar characteristics adressing researchers at different stages of their career:

ERC Starting Grants addressed high potential projects, led by talented researchers at the stage of establishing their first research team or project. This sub‐programme offered research grants of maximum 1,5 million euro.

ERC Advanced Grants supported excellent high‐risk frontier research projects led by established researchers and offered 2,5 million euro per grant. Additional funding opportunities were available for: (1) integration of small research groups working on the same project (Synergy Grants); (2) ERC grant holders supporting their efforts to transfer their research outcomes with innovation potential closer to market (Proof of Concept); and (3) grants for reserachers starting their own new individual reserch teams (Consolidator Grants). Three criteria were applied for the evaluation and selection of research proposals: (1) quality of the proposed research project; (2) the track record of the principle investigator; and (3) the research environment of the host organization. FP7‐IDEAS

Total EC contribution % of EC (in million contrib.

euro)

number of projects

ERC Starting Grants

ERC Advanced Grants

ERC other activities

Subtotal FP7‐IDEAS

3.115

3.708

851

7.673

2.315

1.700

510

4.525

7%

8%

2%

17%

average EU number % of contribution of partici‐ projects

per project pations

(in 1000 euro)

9%

7%

2%

18%

2.714

2.076

615

5.405

1.345

2.181

1.669

1.696

average partici‐ pations per project

1,17

1,22

1,21

1,19

average EU contribution per participation (in 1000 euro)

1.148

1.786

1.384

1.420 Compared to FP7‐COOPERATION the FP7‐IDEAS programme was different in several ways: o

In contrast to FP7‐COOPERATION in which only research consortia from at least three countries were invited to apply for funding, FP7‐IDEAS, invited individual researchers to submit their proposals. As a result, the average EU contribution per participating organization is five times higher than in FP7‐COOPERATION. o

ERC grants were rewarded to individual researchers (and not to the organizations they worked at) in order to strengthen their position and independance. As a result, the average contribution per participation (1,4 million euro) is five times higher than the average in the whole of FP7. Lastly, the average number of participations per project in FP7‐IDEAS is only 1,2. o

While FP7‐COOPERATION was programmed in a top‐down way, FP7‐IDEAS relied on a bottom‐up conceptulaization of research themes and priorities. As a result, every idea from every scientific discipline could be submitted for ERC funding. While FP7‐COOPERATION aimed to address grand societal challenges and ensuring high economic and societal impacts, FP7‐IDEAS aimed to increase scientific outputs, outcomes and impacts. FP7‐IDEAS primarily addressed the needs and logics of researchers in university environments. Instead of defining research topics ex‐ante and expecting researchers to collaborate following well‐defined work plans, it gave freedom and flexibility to the individual researcher to pursue his/her ideas. FP7‐IDEAS created a unique pan‐European research funding organization, established an open, direct international competition, and identified and supported the best scientists. Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 3.6.

21

FP7-PEOPLE – building human resources, mobility and networks

The specific programme FP7‐PEOPLE aimed to improve the qualifications, mobility and networking of researchers all across Europe. The programme builds on nearly two decades of experience, since the origins of this specific programme are already present in FP4. While only 11% of the total budget of FP7 (approx 4,8 billion euro) was allocated to FP7‐PEOPLE, this specific programme accounts for 43% of the total funded projects. FP7‐PEOPLE funded both individual fellows and project consortia. Sub‐programmes "Initial Training", "Industry Academy Partnerships" and other activities were implemented in consortia, while sub‐programmes "Career Development" and "World Fellowships" mostly funded mobility of individual researchers through living and mobility allowances, as well as contributions to training and research costs, management activities and overheads. Besides funding the mobility of researchers, FP7‐PEOPLE also established European‐wide Doctoral degrees, such as the Innovative Doctoral Programme (IDP) and the European Industrial Doctorates (IED). FP7‐PEOPLE

Total EC contribution % of EC (in million contrib.

euro)

number of projects

Initial Training

Career Development

Industry Academia Partnerships

World Fellowships

other activities of FP7‐PEOPLE

Subtotal FP7‐PEOPLE

2.175

1.482

415

665

40

4.777

655

6.303

330

3.061

366

10.715

5%

3%

1%

1%

0%

11%

average EU number contribution % of of partici‐ per project projects

pations

(in 1000 euro)

3%

25%

1%

12%

1%

43%

5.611

6.442

1.402

4.473

1.587

19.515

3.321

235

1.257

217

110

446

average partici‐ pations per project

8,57

1,02

4,25

1,46

4,34

1,82

average EU contribution per participation (in 1000 euro)

388

230

296

149

25

245

Similar to FP7‐IDEAS, the specific programme FP7‐PEOPLE did not stipulate any themes or topics, but allowed submission across all disciplines and all themes. The proposals were evaluated according to five criteria: (1) scientific quality; (2) potential for transfer of knowledge and training; (3) the track record of the grantee; (4) synergies in implementation; and (5) expected impacts. FP7‐PEOPLE contributed to building up human resources by supporting the mobility of individual researchers on the one hand, and by supporting consortia and networks on the other. By funding individuals and not organizations FP7‐PEOPLE empowered rearchers to choose their topics and mobility paths. In order to achieve synergies it could be considered to put the responsibility for implementing the Marie Curie Actions in the same hands as the implementation of the ERC programme. Commitment and Coherence – Ex‐Post Evaluation of the 7th EU Framework Programme 3.7.

22

FP7-CAPACITIES – addressing specific needs in the innovation systems

The specific programme FP7‐CAPACITIES was set up with the purpose of strengthening research infrastructures, their use and development across Europe. While FP7‐CAPACITIES accounts only for 8% of the total FP7 budget and 8% of the toal funded projects, it addressed a broad variety of policy objectives and target groups: it supported the construction of new research infrastructures; the involvement of Small and Medium Sized Enterprises (SMEs) and of Society in EU wide research; aimed at creating regional networks; supported international cooperation; and the coherent development of research policies and research driven clusters. Due to comparably large size of consortia (especially in the sub‐programme "Research Infrastructure") and relatively low average total contribution per project (in all other sub‐programmes) the average contribution per partnering organization was only approx 200.000 euro and thus substantially lower than found in FP7‐

COOPERATION and FP7‐IDEAS. FP7‐CAPACITIES

Total EC contribution % of EC (in million contrib.

euro)

number of projects

Res. Infrastructure

Res. for the benefit of SMEs

Regions of Knowledge

Res.Pot. of Conv. Regions

Science in Society

Coherent dev. of res. policies

International cooperation

Subtotal FP7‐CAPACITIES

1.528

1.249

127

378

288

28

173

3.772

341

1.028

84

206

183

26

157

2.025

3%

3%

0%

1%

1%

0,1%

0,4%

8%

average EU number % of contribution of partici‐ projects

per project pations

(in 1000 euro)

1%

4%

0%

1%

1%

0%

1%

8%

5.267

9.124

1.005

307

1.820

131

1.393

19.047

4.482

1.215

1.508

1.834

1.576

1.087

1.105

1.863

average partici‐ pations per project

15,45

8,88

11,96

1,49

9,95

5,04

8,87

9,41

average EU contribution per participation (in 1000 euro)

290