North American Terrestrial Vegetation

North American

Terrestrial Vegetation

Second Edition

Edited by

Michael G. Barbour

William Dwight Billings

=corred deciduous io'ess;

5aands; .^'=.Aopzlachian

_re<u; P= coaszl plain íorQ=:rup:ca! róresr$. Bou.rd-

g ro W. D. Bi!:ngs; zn

CAMBRIDGE

UNIVERSITY PRESS

Contri

Prefac

Prefac

PLSLKHHED BY THE PRE55 SYVD!CATE OF THE C\:VER:T: iF CAVBR:D-E

Tne Fitt Building, Trumpington Street, Car.:bridge, Lnited Kir,dom

CAYMSRI DGE C4.ERS,TY PRESS

The Edinbur,h Building, Cambrid _ e CB? _RU, LUnited Kingdom r ,1+'ti..c.:p.cam.acuk

40 \Yest ? O:h`Srreet, Ne w York, NY 1 001;=21 i, CSA ,+'x-vr. cap.org

10 Stamford Road , Oakieigh, Melbou :-te 3; ^5. Australia

Ruiz de Alarcon 13, 25014 ,-Madrid, Spain

CHAPTER 1

Arctic

Latrrer

CHAPTER 2

The Ti

Debor.

CHAPTER 3

Forest

Robe,

CHAPTER 4

Pacifi,

Jerry F

CHAPTER 5

Califo

Micha

CHAPTER 6

Chapa

Jon E.

CHAPTER 7

Interr

N'eii E

CHAPTER 8

Wa rn

James

CHAPTER 9

Grass

Phi!1ip

CHAPTER 10

Easte;

Hzzc,

CHAPTER 11

Veget

N'or,m,

CHAPTER 12

Fresh

Curar=

CHAPTER 13

Salta.

In iro

Cs Cambnd ,e Cniversity Press 2958, 2300

This book is in copyright. Subject to sta.`cton' escephon

and lo the pro\isions o£ relevant collectice '. icensn, agreements,

no reproduc tlon of am- part mav take place t. ithout

the ., r.tten permission of Cambridge Universri' Press.

First publ!shed 1955

Second edi on 2000

Pnnted in the Cnited States of Amenca

Tv?cfr:e, 9/11 Palatino pt. DeskTopPro Ln IRFI

A ca:aing rcccrd for ilds book is n,:.riloble 5em f e Eritislr Librare.

Lrr,-v of Corgress Ca:aI ^i,rq-in-A,b'ics;ian Gas

North American terrestrial vegetation / edited by \S:hael G. Barbour,

William D,.'ight Billings. - 2nd ed.

p. cm.

'nclndes bibliographiczl referentes (p. ) en-' índex.

ISBN 0-521-55027- 0 (hardhcund)

1. P!ant commnni:ies - North America. 2. Plant ecology - North

.America. Phvtereo,raphv - North A-, eric a. 1. Barbour , '1ichael G.

II. Biilings, W. D. Q1'illiam Ació t), 1910-;997.

QK11 O.N854 1999

551.722097 - de i

ISBN 0 531 55027 0 hardback

ISBN 0 521 55956 3 paperback

9729C'cl

CIP

CHAPTER 14 Alpir.

CHAPTER 15

Meza,

A!e;.,

CHAPTER 16

The C

Are!

CHAPTER 17 Tro,n

Contents

Contribulors

Preface to the First Edition

Preface to the Second Edition

HAPTER 1

Arctic Tundra and Polar Desert Biome

page vi¡

ix

xi

1

Lawrence C. 3liss

41

CHAPTER 2

The Taiga and Boreal Forest

Deborah L. Ellon-Fisk

CHAPTER 3

Forests and Meadows oí the Rocky Mountains

Roben K. Pee:

CHAPTER 4

Pacific Northwest Forests

Ierry F. Frankii❑ and Charles B. Ha!pera

CHAPTER 5

Californian Upland Forests and Woodlands

Michael C. Barbourand Richard A. Minnich

161

CHAPTER 6

Chaparral

Ion E. Keeiey

203

CHAPTER 7

Intermountain Valleys and Lower Mountain Slopes

%eii E. L1'est and la .mes A. Young

255

CHAPTER 8

Warm Deserts

James A. Mac.^;ahon

285

CHAPTER 9

Grasslands

Phil!ip L_ Sims and Paul C. Risser

323

CHAPTER 10

Eastern Deciduous Forests

Haze! R. Delcoun and Paul A. Delcou: r

357

CHAPTER 11

Vegetation oí the Southeastern Coastal Plain

397

23

Norman L. Christensen

449

CHAPTER 12

Freshwater Wetlands

CHAPTER 13

Saltrnarshes and.\langroves

Irvin, A. Mendelssohn and Karen L. McKee

501

CHAPTER 14

Alpine Vegetation

William Dwight Billings

53%

CHAPTER 15

Mexican Temperate Vegetation

Alejandro Velázquez, Victor Manuel Toledo, and !solda Luna

573

Cunisl. Richardson

CHAPTER 16 The Caribbean

593

Ariel E. Lugo, Julio Figueroa Colón, and Frederick N. Scarena

CHAPTER 17

Tropical and Subtropical Vegetation of Mesoamerica

Gary S. Hanshorn

623

W. D. Bi/!ings

,.d 'oil develop\!'_:dro^. C- ac er,

G. Molenazr. L,

:crs in z:Cic and

unes, R. W. Hoharn,

fed>-) The ecologv

Carnbridge.

;.,D. 1\'a!ker, and

.,. studies of

.enze +_.-S ^,'5. Czrboh drate

^Le plants..amer.

of paterned

bu'.l. Geo_c<ta Rica und itere

-, rrit den Ho.n 1?athematischiz^.: gan,e XR 3.

und der Literz;ar.

:I lir.ts of vascular

Chapter

15

Mexicali Temperate Vegetation

ALEJANDRO VELÁZQUEZ

VICTOR MANTUEL TOLEDO ISOLDA LUNA

S74

A.

Velázquez,

DIVERSITY AND NEARCTIC AFFINITIES

Mexico has a high diversitv of ecosvstems iRamamoorthv, Bye, Lot, and Fa 1993). Mexico includes

six oí the ten major terrestrial biomes oí the world

-extra-drv vegetation, mediterranean, temperate

forest, temperate grassland, montane, and tropical

rain forest (Cox and Moore 1993) - and it is one of

the ten most megadiverse countries oí the w'orld

(Mlttermeier 1988), harborirg 10-12% oí the

world's vascular species (Toledo and Ordoñez

1993)Mexico's vide elevation range (0-3000 rn), its

location astride the Tropic oí Cancer, and the influence oí two oceans across its reiatively narrow'

continental mass probable are determining factors

for the most significant features oí Mexico's climatic diversity. The Tropic oí Cancer is a significant therrnal demarcation and also deli.-nits the

transition between arid and semiarid climates

arid anticyclone high pressures toward the north

versus humid and semihumid trade winds and cyclones in the south. The complex ph\siography,

together with the differences determined by latihude and altitude, result in a climatic mosaic with

a great number oí yariations (García 1951). Maximum average temperatures (288-30° C) are recorded in the low-hing regions oí the Balsas Depression, w-hereas adjacent zones at -he top oí Pico

de Orizaba in Veracruz hace the iorest average

temperatures (-6' C). Some mountains Nave glaciers and permanent snow. Apart from these tw•o

extremes, the range oí temperatures most frequently recorded caries from 10 lo 2S° C. Precipitation also presents notable contrasts: from <50

mm annuallv and no wet season (as in parts oí

Baja California) lo >5500 mm annually and almost

no drv season (as in parts oí Tabasco and Chiapas).

As a consequence oí this climatic diversity,

Mexico has a largo variety oí vegetation types,

comparable only lo India or Pena. Altnough detailed studies haye distinguished up to 70 different

units of vegetation, based on phy'siognomc and floristic composition, it is possible to differentiate

fewer principal tapes of vegetation in Mexico at the

biome category (e.g., West 1971; Rzedow ski 1978,

1993; Flores 1993). At such a scale, it is apparent

7har.ks lo Martha Cual and R. M. Fonseca for support

en floristics. Comments by Jorge Llorecte, Javier Madrigal, and Richerd Minnici on an ear!y iersion, and bv

>tichaei Barbour on a late' version, are acknow!edged. J.

Rzedowski fully encouraged the preparation oí this chapter, and it vas further supported by a grant-in-a.'d from

DGAPA-GN.AM grant IN-209094, and FGO's Universiw

of Amsterdam.

V. M. Toledo and 1. Luna

Temperater

1 egetation

that Mexico mar be divided relatively easilv. Fin

ure 15.1 shows the distribution oí the main vegetation tepes oí Mexico as a function oí two clima tic

attributes: precipitation and temperature (the latter

is represented by eievation in the figure).

Although mane Cosmopolitan and Paleoarctie

taxa are present L-i Mexico, its geegraphic location

has favored the establishment cf hiotic elements

characteristic oí %vo main regions, Nearctic and

Neotropical. Mexico is si;uated un a transitional

,; adient from Neotropical to Nearctic environmer,ts.

A large part oí Mexico is dominated by ecosv°terns oí northem af fiiiation (Beard 1944; Rzedowski

1978). Two main historical events may explain the

present dominarce of arctic biota: (1) most oí Mexico's northem territorv has been linked permznen;k lo the rest oí North America, and (2) the last

glaciation (ca- IS,000 Nr ago) promoted the moyement south oí .mana northem taza within Mexico s

present political horders (Fe:rusquia-VÜlafranca

1993; Velázquez 1993:.

Temperate vegetation tvres on long north-south

mountain chains tcpifv Mexico's arctic affinities.

The Madrean Region from no7inem Mexico south

through the Xeovolcanic Transversal Belt lo Las

Cañadas de Chiapas is dominated by oak, alder,

p:.ne, and fir species. The absolute dominance oí

species oí Nearctic origLn che tree iayer and a

large number oí species oí Neotropicai origin in

the shrub and herb layers is commonly obsen'ed

(Gadow 1930). T,tic compiex ceeetztion patiem becoma more dominated by the Neotropical to the

south and bv +-he Nearctic lo tE:e north. T'ne Neocolcanic Transversal Belt tenis the heart oí the

gradient, and it contains a lame number oí endemic taxa (Fa 1959; Rzedow.wski 1993).

Data from a lar ge nuniber oí botanical and zoological expeditioti throughout tñe present centun

provide strong evidente oí `e great affinity of

montane regions of Mexico wi:h the rest oí North

America (Beard 1911; Goldman and Moore 1945;

Srnith 1940; Troll 1952; Wagner 1964). Structural

classficatiors oí Mexican vegetation tupes equated

temperate ecosvstems •.with mountanious regions

(Sanders 1921; Shelford 1926). Temperate montan e

vegetation tepes pave ra-ieusl;- been called (Table

15.1) montane raLn. forest, high m

.ountain forest,

and páramo (Beard 1944; Braman 1962); pine-oak

forest (Leopold 1950); low e.erreen forest, conifer-oak forest, oak forest, and :-,amo (Miranda

and Hernández-X. 1963); and mest recent!v cloud

montane forest, cornierous forest, uak iurest, and

grassiand (Rzedowsski 1978). Research that defines

the relationship oí these vegetation tapes lo ecological facters such as humidity, ssoil suitabilit',

5000 -____-___

2000 -__

i

:000 --TRi

e

I

3000

Hvperhumid Hu:

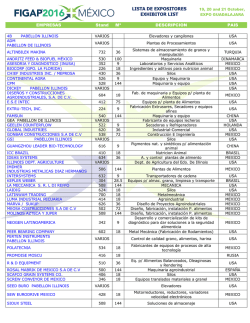

Figure 75.1. Maior.M,exka

a!ong gradients oí tempera:

rainfali in mi!!imeters). Abb

(TRF), subtr-oical caduciró

tbbus iorest T(1F), shrublan

Table 15.1. Equivaleni r

tarious authcrs

Beard (i 955) Herr

Montare rain iorest Deci(

.Montare iorest Pine

Páramo Alpin

Source: Rzedcvrski. (1978).

fire, number oí days w'iti

and mean anual prec:

scanty or restricted lo sr

initions oí temperate -\le

eeer, Nave been ¡nade

and Ordoñez 1993). M.

matic ecoregions are the

humid temperate, and

15.2).

3 and I. Luna Temperare l'ege:ai;on (Mierico

575

v easily. Figmain vegen,o climatjc

cre (the latter

_.e).

Cold

:d Paleoarctjc

spic location

5c elements

_ .carctic and

a trans_itional

rctic environ.

Semicold

Températe

Températe

ted by ecosvs1; Rzedosyski

ay explain the

:m,ost of Mexinked perraaand (2) the last

ted the moveaitin Mexico's

uja-Villafranca

ng north-south

rctic affinites.

Mexico south

sal Belt to Las

by oak, alder,

dom

,Lnance of

ce layer and a

pical origin in

ronly observed

ic n pa ttern be'cupical to the

crth. The Neoe heart of the

,.umber of en+3).

nical and zooresent centnrvv

eat aff ruty of

Test of Nonh

3 Moore 1945;

64). Structural

hiles equated

:nious region

erate montane

n calied (Tabie

,untain forest,

962); p,e-oak

n forest, coniamo (Miranda

recently cloud

,ak forest, and

;h that defines

types to ecooil suitability',

Sem v arm

\Yarm

\'erv \1'arrn

Semiarid Ard Hv^perarid

Sub.hum d

Hvperhumid F. =d

Transition

Trarsidon

Figure 15.7. Major Mercan vegetation ;upes ordir,ated

alon;S g^adien.s or ;erPper arare and precipCation (anm:al

rainiall in milümeter<i A±brevi tions tropical ruin tares;

(TRF,t subtropical caduc;rolius [ores; (Sri, tropical caduci-

(SAG), t.homshwb (T5), oak lores; !OF', cloud forest (CF),

rir [ores; !FR. pine lorest (PF), and alpine grassland (A C).

The nical zone is IC. (Modified rrom Toledo d RzedoHSki,

1995.)

[ollas [ores; (TCFh shrub avd íA, subafpine erassiaad

Tab'.e 15.1. Equ[va!er„ carnes ci ASexican :enoerate s ege'a?ion rypes ,iver, by

varicurs authors

Toledo &

Miranda &

Beard (1955;

. ernandez.X . ; 1963)

ntontane ram lorest

D eciducus lorest

.Montare forest

Páramo

PI^-e-ilr lorest

- .or ne bun..cir grass!acd

Rzedo,ski ; 19781

C:'ou ores;

Comer lorest

'taca;on.al"

Ordoñez;1993)

Hurnid temperare

Subhunid temperare

Cool temperare

Source: Rzc Jowsk;, t19-2:.

fire, number of daos -.,:th temperatures below teto,

and mean anual precipation is, on the schole,

scantv or restricted to specific places. General definitiors of temperate Mexican environments, hos+ever, hace been made (Rzedowski 1978; Toledo

and Ordoñez 1993). Major temperate biogeoclimatic ecoregions are the humid temperate, the subhumid temperate, and the cool (or alpine) (Fig.

15.2).

Tre humid temperase repon is characterized by

cloud forests dominated by oaks. Tse forests' tloristic composition includes beth boreal and tropical

elementü. This region nccupies yery restricted sites

of 600-3200 m elevation, mainly on slopes facing

the Gulf of Mexico from Tamaulipas tu Chiapas.

Distrbuted in 21 states, it covers an atea of approximateiy 10,000 km'.

The subhumid temperate region covers the

576

Temperate Vegetation

.4. Velazquez, V. . M. Toledo and 1. Cuna

0 2).

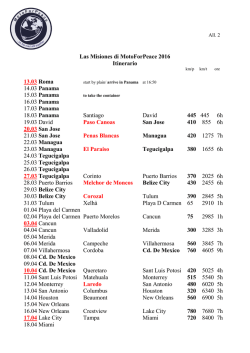

Figure 15.2. Climatograrx representad; e of thr ee nain ele'a:ion befts or nountain environmernr temperare humid

(Tlanchinoli, temperare subhumid iEl Guarda), and tempera:e cool :Hueuedaco). Months Jancan-DecemSeri are arranaed along the horizontal axis, mean monrh„S remperature along the lert rerlical axis, and monrhly p-ecipiration

greatest parí of the mountains of Mexico at elevatiotu of 2500-3000 ni. The characteristic vegetation

is forest of fir, pine, oak, or mixtures. It s distributed through 20 states (principally Chihuahua, Michoacán, Durango, and Oaxaca) and covers an area

of approximately 3_3,000 km'.

The cool (or alpine) region is located aboye timberline (>4000 m) on the 12 his,hest mountairs of

Mexico. It is dominated by alpine bunchgrasses, or

zaca tonales.

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION

OF TEMPERATE VEGETATION

Mexico is a ver, mountainous countn,, with over

half of its territon- >1000 m in elevation. Arid and

semiarid vegetation dorninates the high plateau of

central and northern Mexico, whereas temperate

vegetation (as defined in this chapter) covers the

steep and more humid areas ahoye 1000.n. Temperate vegetation thus covers 2200 of the Mexican

territon•. Mexico is also a countn- with evidente of

past volcanic activity. The most spectacular volcanic area is the great Neo;olcanic Transversal

Belt, which crosses Mexico from west to east at the

latitude of Mexico City (19-204). its landscape is

characterized bv thousands of old cinder tones and

dczens of tal) volcanic peaks (Fig. 15.3). Volcanism

continues todas', with many active or temporariiv

dormant volcanoes.

Earthquake activity is common, mostly along

the Pacific Coast and the Gulf of California. Earthquakes are also frequent in the Neovolcanic Trans-

along tne right verical axil. F'e Bical shading represe,-'s

soi1.rnoisture recharee ; solid srac,nc reoresenr$ precipi:ation bevond soil smraee caoacn, and doned shadi, represe%-5 soil mo .ivu: e derlc;r. Pa, ;Sienta) ir,rorma:/on is e,

e'a:ion, mean annual tempera:cre. acd an.- jzl

precip;:arion. Cii.ma:ic data a,e a' ere; es or :930-1990.

verse) Belt, often ca ❑sing considerable damage in

this heavily populated region.

Mexico can be divided finto five general rea':ras:

ext-atropical dn'lands, tropical highlands, tropical

lowlands, extratropical l gF.lands, and subhumid

lowlands (STest 1971). Diese realms match most

Mexican phvsiographic regions - Lar exampie, the

Baja California and Buried Rarees of northwest

Mexico, the western and eastem Sierra Macires, the

Neovoicanic Transversal Be!',, and the Highlands of

southem Mexico. Four repon q are considered temperate: the western Sierra Madre, the eastem Sierra

Madre, the Necvolcanic Transversal Belt, and th,e

southem Sierra Madre.

ic westem and ezstern Sierra Madres forra

dissected borders of the;vestern and eastem, edees

of :he central piateau. The croad crest of the western Sierra Madre vises up to 3000 m. The upeer

portion of the range is covered with thick lavers ef

lava. The western slope of -,he range forras rueged

can\ons and narrow ridges dropping down to the

Pacific coastal plain. The eastem Sierra Madre rises

to a sharper crest on the eastem rim of the central

piateau, with elevations up to 4000 m. In the

North, the Sierra is comprised of severa; irregular

ridges separated bv baria descending graduaily to

the Golf coastal p lain.

Tne Neoyoicanic Transversal Beft forms a maior

geological break ;, ith the central plateau. The belt

is hnrdered en the north bv a series of high bas:nS

on the south the )and drops sharply mito the drrr

Balsas Depression. included in this volcanic area

are Mexico's highest and best known peaks: Pico

Figure 15.3. o gital eles

me Vallev of México ' e:

de Orizaba (5700 m),

cíhuati (52S5 m), and

The Highlands o:

logically complex re

tions b'c the Isthmus

Sierra Madre in the

;ande in the east. ??-.

highly dissected mu

vailevs, a discontinu

a few highland basin

are dcminated bs- tl-,

teau rising up to an

These regions oc

Coahuila, Nuevo Lec

Luis Potosí, jalisco, c

Distrito Federal, Pu.

choacan, Oaxaca, ar

tened regions in the c

species: high elevatic

Baja California Sur, C

erra Fria in Aquasca

Sierra Lacandona aa

MAJOR TEMPERAT

VEGETATION TYPI

}

The four major ter^p

ico are comp^xd

(s,,:su Rzedow 'ki

Beard 1941 and Brau

can classifications ar,

laven and at ihe gene

phasis masks consic

leve). Fir forest (.

577

Temperate L'egeiation of ,\lexico

Digital £1"ation Nade]

Ajusto ( 3990 s)

Fi;ure 75.3. Dita! eleuaon model or southern portion o7 crea oi 805 kr are >J00 vo,'caric eones. From Velázrhe Vallev o México ;vericel exagaeration 3x:. )vithin Ihis quez 7993.)

7990.

.' dam age in

_._ral reair^s:

ropical

..;, subhumid

_ match rnost

epa-:ple, the

cf northwest

7a Madres, the

e Hi^iilands of

_r_.dered tem,e_stem Sierra

1 .,_.., and re

.ladres forro

cartero ed-_es

st cf tire westm. The upper

.,ick lavers oí

_ orms rugged

g do••Vn to the

ora Madre r,ses

.. of the central

:33 m. In C,e

.coral irregular

ng gradua„\ to

t forros a major

'.ateau. The belt

of high basins

v finto the deep

s co!canic area

n peaks: Pico

ce Orizaba (5700 m), Popocatépetl ( 5.1=2 m), lxtaccíhuatl (5255 rn), and Nevado de Toluca (4392 m).

The Highlands of southem Mexico are a geologically complex region separated oto hvo sections bv the isthmus of Tehuantepec : 'he southem

Sierra Madre in the west and tire Chiapas Highlands in tire east. The southem Sierra Madre is a

highly dissected mow,tain svstern w'ith narrow

vallevs, a discontinuas Pacific coastal plain, and

a few high!and basins. Tire southeastem highlands

are domi:nated by tire altiplano of Chiapas, a pieteau rising u,,- te en ele\ation of 2500 m.

Tpese regio.r.s occur in Chihuahua, Durango,

Coahuila, Nuevo Leon, Tamaulipas, Zacatecs, San

Luis Potosí, jalisco, Guanajuato, Hidalgo, Mexico,

Distrito Federal, Puebla, Veracruz, Morelos, Michoacan, Oaxaca, and Chiapas. Sorne other scattered regions in tire country also harbor temperate

species: high elevations of Sierra de San Lazaro in

Baja California Sur, Cerro Potosí in Tamaulipas, Sierra Fria in Aquascalientes, and high e.evatior<of

Sierra Lacandona and las Canarias in Chiapas.

1tA)OR TEti1PERATE

VEGETATION TYPES

Tire four major temperate vegetation upes of Mexico are comprsed of many plant comrtunities

(ser;e;r Rzedowski 1978) or associations (sensu

Beard 1914 and Braun-Elanquet 1951). Most Mexican ciassifications are purely based on tire canopv

layer and at tire generic level (Tabie 15.2). Tnis ernphasis rnasks considerable variation at tire species

level. Fir forest (A.cies), for instante, occurs

Tahle 15.2. Chzracreri;tic eecera or the Tour majo

temperare vegetar:on rape; o7.tfexico. ;hese genera

mav van' iro.m slooe :o sfone and moro sierra to

siena, so thar no single genus can be round

:hroughout a single temperare +egetation rype.

Cloud

Gene a

a^^<

t'.ein.vu.n,nia

forest

Pirre

ic'est

Y

X

x

Liquidaabar

x

Acer

x

iüa

x

Aluhtenéerla

ti

Ribes

x

x

x

x

He:e-ia

x

Cier^NJm

x

Roícana

3odd!eia

T udwm

Sh !ro pia

S2iz

Cirr:a

Srmphoricarpos

Alplne

grassland

x

cr.=e.tha«1:ia

Celos

Bacchariss

Fir

forest

X

X

x

x

x

x

x

Ca!amagros:is

x

A^roslis

x

Ttiselum

L'.mbilica ria

Bry oepihrophyllum

Siereocaulon

Cladonia

x

X

X

X

X

5 78

throughout Mexico, but co-dominant shrub species

and fir species change from north to south (Velázquez and Cleef 1993; Islebe, Cleef, and Velázquez

1995). Only a few phvtosociolodca] studies have

been conducted in central Mexico, sufficient to define associations and alliances based en fine-scale

differences in species..Another limitation to our

ability to summarize the vegetation is that a large

part oí the territorv where temperate vegetation

types are distributed has not been sun eved in detall. This lack oí homogeneous informa tion does

not permit us to provide a thorough description oí

al¡ communities. Thus a detailed description oí

temperate vegetation is beyond the scope this

chapter.

Our objective is to provide an ovenview oí major vegetation tepes and to emphasize those tha;

have been best studied. We also intend te outline

the consenation possibilities for temperate vegetation in Mexico. Additional details on the vegetation oí Mexican forests, grasslznds, deserts, alpine, and wetlands are found in Chapters 3, 8, 9,

13 and 14 oí this volume.

Cloud Forest ( Humid Temperate Forests)

Large biological heterogeneity t-pifies a cioud forest, which is a mix oí northem, southem, and endemic taxa , and oí ]ow- and upper-elevation laxa.

Because oí its diversit-, various .-.ames have been

given to Lhis vegetation tvpe; bosque mesófilo de

montaña (Miranda 1947), caducife'ious forest (Miranda and Hernández -X. 1963), temperate deciduous forest (Rzedowski 1963).

Five environmental requirements seem to govem the presence oí cloud forest Li Mexico: high

relative humiditv, montarte en;ironments. irregular topography, Jeep litter laye:, aad temperate el¡mate. Cloud foress covers at most 1% oí the total

Mexican surface, but it includes about 3000 vascular species (Rzedowski 1993), which is 12% oí the

countrv's vascular flora (Toledo and Ordoñez

1993). Currently, there are only a few large preserves oí cloud foress but thev are scatered

throughout the range oí the tepe.

Aiong an elevation gradient, the structural complexity oí cloud forest decreases totvard high e'.evations and varíes from slope te slope. Elevation

ranges from 600-3200 m, though trae vegetation a

best developed at 1000-1750 m. Precipitation :s

IS00-5500 mm }-r', and doudiness is commo;t

throughout the year. Freezing temperatures are

rare. Major temperature changes are seasonal, in

contrast to large daily changes un alpine environments at higher elevatiora.

A. Ve!azquez, V. M. Toledo and 1. Luna

Phvsiognomically, cloud forest is dense, 15-40

m high, and multilayered (Fig. 15.4). Some oí the

tree genera that reach more than 40 m are Engeihardia ard Pi.^.tanus. Tne upper free la}•er is dominated bv caducifolious (deciduous) taxa, the lower

tree laver bv perenrüo!ious (evergreen) ones. The

most diagnostic species is Liquidmnhar rnncnephu:'.:

(see Fig- and the most common associated

boreal elements are Ca-vinos caroliniar.a, Cornos disnjlora, Ti! mexicana, .4.'nos f, rn:yfolia, and Qnercus

car;dicros (Miranda 1947; Puig 1970). Some species

shared rvith the eastem deciduous forest oí North

America are Acer r:egundo, Carpinus carolinana,

Carca orcta, Cornos onda, Fagus mexicana, lllici:un

^9oriu'.aruat. Liquica.n:ber nz:rophy!la, Nyssa sylt'afica.

Oshva -i•cir, irisa, Pra:us serotina, Ti!ia foridana,

and Taxurs globosa. Species shared with western (oíten riparian) foress are Arsu:us xa!cpersis. Cei:is

pailid C. ret:cu!uta, and 5„mbucus mexicana. Mesoamerican Laxa f:eeuently, foud in cloud forest are

Clet!:ra spp., l"+eir:n:a; ✓ :: spp., Arctataphvlos argufn,

Ilex discokr, Litsen gia c scens, Magnolia schiedca nt,

Pinos :r;ontezun::.e, P. ps:udestrobos, Prunus brachyhotr✓a, arad Uimus mexisma. Among the endemic

taza are Canco eruta var. mexicana, Ilcx pring!ei, Juglans mol!:s, and P!atanus mexicana (Rzedowski

1978).

Commonly, there are wo shrub layers, both

with Neo:ropical al les- T,.e families Compost

tae, Gesneriaceae, Ciusiaceae, Labiatae, Legurninosae, Malvaceae, Me astomataceae, MyrsLnaceae,

Piperaceae, and Rubiaceae varousiv dominate, dependLng en elevation, !atitude, and humidity.

The herb laver Lncreases cover and diversitc

when the oversto:v is disturbed. Arboreal fems

(e.g., Cya:%rea) are comnion, as well as herbaceous

species. Mosses are aba-ndant. Flowering piants are

in the fzmilies Asclepiadeacea, Begoniaceae, Bromeliaceae (especialls' the genus Tillandsia), Cvperaceae, Compositae, Convolvulaceae, Cucurbitaceae, Dioscoriaceae, Equisetaceae, Gramineae,

Liliaceae, Lvcopodiaceae, Orchidaceae, Piperaceae,

Solanaceae, Urticaceae aad 1'erbenaceae. This ]ayer

has a Nectropical afí n-:, :.ith only a few rnosses

and mushrooms be", ci boreal afiinity (Crum

1951; Guzmán 1973; Delgadillo 1979).

Pine Forest (Subhumid Temperate Forests)

Mexico contains about naif oí the 1, orld's pire species (Critchfield aid Little 1966; Shles 1993). in

mu,i arras pino forests are co-dominants with

other broadleaf trees (AL;us and Quercus) and other

conifer species (Abies and Juuipen:s). Collectiveh

they, cover 1596 oí Mexico: on sandy soils of coastal

Temperate t

<

lag --

plains (Pinos

michoacmrus, ,'

(P. hartwegñ),

15, C- 10)a

not seem te

ment oí pine

sociated with

Hernández 19

Rzedowski

disturbance i^

of conifers, b,

shown that

succession tm

study is n =edc

grazL 0 en pir

fleco and 1. Luna

Temperare Vegetation oi.Mexico

579

is dense, 15-40

Some oí the

m are Engel_e laver is domi) tasa, the lower

,,creen) ones. The

,,tbar mr<crophypa

nmon associated

1 tia ra, Cor,;us dfsand Quercas

Some species

s forest of North

6:us carolfniana.

-ruL'xicmm, illiciuru

NyEsa sul:'atica,

Tilia floridana,

+ith westem (of,.. apersis, Ce;ris

_ a:exicano. Meso7, cloud forest are

. os tapl:ylus arguta,

?cro!ia sczicdenna,

?ranus brachuong the endemic

I:ex prir:giei, jugara (Rzedowski

:n b lavers, hoth

amilies Composiabiatae, Legurnieae, Myrsinaceae,

:s!v domínate, dend humidity.

per and dicersity

J Arboreal fems

ell as herbaceous

wering plants are

3egoniaceae, Bro'd:anisia), Cvper:eae, Cucurbitare, Gramineae,

cene, Piperaceae,

acere. This laver

nlv a few mosses

i affi dty (Crum

,79).

ate Forests)

sorld's pine speStvles 1993). In

-domL,ants with

uercus) and other

-ia). Collecñvely,

'.v soils of coastal

FI, ure 15.=. Asoect oí cloud forest at

encelo anea (2600 m). ICounesy oí

1. L. Convexas)

plairs (.Pü¢us car:b..ca, P. oocarpa), en lava flo•.+s (P.

michoacanus, P. *..-..,e.urrac), and at high elevarions

(P. kartaegif), (Rzedos+ski 197S). Temperature (ca.

15- C = 10) and precipitation (S00 = 150 mm) do

not seem to be .actors for the establishment oí pine speces. Acid soils, how+wever, are associated with pine íorests (Aguilera, Do,,', and

Hernández 1962).

Rzedo,+'ski and v?cVaugh (1966) state that fire

disturbance in pire forest favors the establishment

of corifers, bu t Sa ..chez and Huguet (1959) have

shows that fire, loó ing, and grazing induce

succession toward pine-alder-bunchgrass. More

studv is needed to document t-he e.`fect of fire and

grazing on pine forest (Velázquez 1994).

Major tupes of pine forest inciude alder-pire,

ponderosa pire, pine-oak, Hartxeg pine, and

mixed pine. Each is described in the following sections.

Alder-pne forest. Alder-pire forest is made up of

four structural lay.ers: (1) coniferous tree layer (50%

cc.ver, masimum height 22 m) of Pinus: (2) sh,-ub

layer (4 m height) of Alnus `nnifolia, Senecio cinerrricdes, and S

(3) dense

burchgrass ]ayer dorninated mai.nly by ,,luhlenbcrqia nmcrcur a and Frstaca tolucensis; and (4) ground

layer componed mairly of Alcheudlia pronm:bens

and Arenaría lycarndic:d s. The bunchgrass )ayer is

characterized by compact bunchgrasses -,+ith

580

A. Velazgoez, V. Al. Toledo and 1. Luna

Temperate Vei

Litsea glnucesc

laver. 'Ylidstai

mentioned, bt

are more dom

sir and 5,un:pic

Cure stage is

laur;na and Q

single species

dant subcanr

(Gonzáiez-Ese

phase is one a.

dominated by

understory (th

depends stron

Intensive r

comrnon in t.

bun agriculh:

ited, mainly a

Pinus hartwegh

scribed this

poor. 11, is mai:

pedregal lava

rather flat ut:;

330373 me

(1 m) are loam

Figure 73.5. Aspect oí pine íorest at Tláloc volcano (3300 m).

broad, long, tough grass leaves that seem to be

,veil adapted to fire and browsing (Fig. 15.5). The

íorest is restricted to ver] dissected, rol'.ino toeep slopes, and lava flo,vs at 2700-3500 m elevation. Soils are shallow i+ith grave'}- sandy loam

texture.

Constant diagnostic species include Alims frmi,`clfa, Arhutas glanduloso, Buddleia pare?ora, Ery»gium carlmae, Pere cn;on ge»tiarcides. P. campar:+Iatus, Pivus monte:Inliae, Qt4'rcus r;urina, Sicyos

1,ar,'ij7erus, Stellaria cuspidata, and Striu nm»arditblis.

Cervantes (1950) and González (1952) described

this ttpe of mixed forest, and Rzedowski (1951,

1975) referred to it as a mosaic of Air::rs finni olía

forest and M;dacuhcrgin gandridentata , assiand and

suggested that repeated buming and grating are

the main causes of the bunchgrass. Disturbed conifer forest in some parts of central Mexico is replaced by alder forest or by suba!pine coarse

bunehgrassland of .\hdiler. bcrgia and Festuca.

Velázquez and Cleef (1993) desccbed four associations ivithin alder-pine forest in central Mexico: Trisctunt alti];i um-Ahlus Frmifoi:r. Pinus-A6:us

fr; folia, Ervngiunt cr. rlinae-A.bu+c, ün :fol(o, and Pi. 77m7ife:unce-Al::us Jtrmi^ólia.

Pinus ponderosa forest. Ponderosa pine is chieflv

found in the western Sierra Madre ori granitic or

volcanic steep slopes or plains at 1021500 m elevation. Fires are frequent. Ponderosa pine dom:

nates large stands, are citen mixed ,vid:

Abies cor;cnlm. Studies of :...- forest's distribution

and d,-namics are scanty in con trast to many

publications about it in ti-e Urited States (Styles

1993).

Pirre-oak Forest ;Pinus oocarpa-Quercus aurina). .\lost landscapes at high elevations (23002i00 m) of Chiapas are covered by pine-oak forest

in sorne stage of recocerv from disturbance (1\'agner 1964; González-Espinosa et al. 1991). Onh' a

fe" patches of oíd-ero,v th forest remain. There are

no freezinng davs dur'ng the %ear. Soils are moderately deep (10 cm) calcarecus or clavey loaras

(Breedlove 1951).

Tnree seral stages - early. middle, and matare

forest - are apparer.t. At ec c stages, Pimis oocur;'a.

P. oaxacar:o. Quere2j9 Q. crass;fnlia, and Q.

rugosa prevail. Beio,,' the overstor' canopy is a ser

ind, io,,cr roe !:ccr i,,niinatei by Ra,anea ¡re,.

genserií and P: u :us serctira. Scla»urn 7igrica7:s and

The physio

layers: (1) an c

(2) a herb-bun

hergia. Festuca,

(3) a ground la

enana lucepec::

tbis forest are

qu.uiridentata; ::

Muhlenhergia

tuca tohrce»sis,

ter hvo bunchs

alpine grasslar

quez, and Lur:

The forest

layers, unlike

and Pelado yo'

,va,•s hace a de

is considered t

Em (1973), hoy

,vas a successic

religiosa forest,

alpine slopes a

gro,vs in a mal

i e_:rnu:e, and Q

.Haca, Nema:

boreal distriba

tains of Centra.

in Guatema!a's

eral plant coro:

••:üé v N:;.'.y;'n-eN '- .`..n '_6. -,

!'w+:^ i o+^ :-.i f 4 . :z

i% ni,'..

I. Luna

L!sca glaucescrns are abundant en the ground

laver. \•Iidstage stands share all the species just

mentioned , but pines are les i,r,portant and oaks

are more dorninant . In addition, Oreop „ i:az ^nlapcusis and Svnq'Iocos li noncillo are abundart. The matare stage is en oak forest don tinated by Quercus

laurina and Q. crass;fo'i a. Pinos are present, but no

single species prevaiis . CL-sera theaou'es is ara abundant subcanopy free. Shrubs are chiefiy abre,,^.t

(González-Espinosa et al. 1991). This pme-oak seral

phase is one of the best examples ef a canopv ]ayer

dominated by Holarctic species with a Neotropical

understorv (though the degree to t.+'hich this holds

depends strongly en geographic location).

Intensive grazing, cepping. and logging are

common in the Cañadas of Chiapas - Slash and

burra agriculture for coro productien is more .'imited, mainly conducted bar indigenous groups.

Pinus hamvegii forest. ?tzedowski (1951, 1978) described this vegetation as being rather speciespeor. It is mainly restric:ed to the upp er part of the

pedregal laya slopes beiow co.'canic rones or te

rather fíat undulating slopes forming plateaus at

3350--3=70 m elevation. Trae relaiive'y >haüow• mis

(1 m) are loamv clays with a thin Iitter la, er (5 cm).

The phvsiognomv of this forest consists of three

lavers: (;) en ove,storv free laver up te 20 m high;

Z) a herb-cunchgrass ]ayer with

e is chieflv

anitic or

.500 m elepine domd-:ixed with

stñbut ora

,t te manar

:ates (Stvles

creas laurr;ons (230

e-oak forest

.anee ('^1ao

a

r:. Tbere are

are mod.avev loares

and matute

cocar:",

and Q.

opy is a sec:::;:,:rea

_;r:crrs and

581

Temperare t'ege!arion of ntexico

Sergin, Festuca. and Cala' :::;ros::s grass species; and

(3) a ground !ayer dominated by.5ldaonaia and Arenara lvcopodioides. The main dia_nostic species of

this forest are Pinas Ccrtm ezíi and A'u1.!enberg-,a

qundridn:'nta; importar., associated species include

..",Qad:lenbergin nuaaeura, .=:r:r:aria lar:opa:üo:.yes, Fe>tuca tciucensis, and Calara:•-mstis tc.t;ic,sis. The 5t

ter rayo bunchgrass species are also diagn:ostic for

alpine grassland f.Almei^a, Cleef, Herrera, Veláscuez, and Luna 1994).

Trae forest lacks -weil-deti.-:ed s,,. and herb

lavers, unlike the Pin:,s i:.r;avri€ forest en Tláloc

and Pelado yolcanoes Ln central Mexico, which alw-a ys ha,.e a dense herb :a ver. Pi ': us 'ss r;;rc; ii f ores t

is considered by most te be a clímax community;

Em (1973), hotvever, s-a _,ested that P.rs:c rsrttrrgii

was a successional species in severel'y bu:ned AFies

n^'r^:bsn forest, a forest res::leed te yen. steep subaipine slopes at 2900-:23-0 m eleyation, and which

nmngro'.+s ir. a matriz tyith

and Qacrc:s /eres: (Pvede'.vski ;954, 1975;

.Anaya, Hernandez, and Madrigal 1980). Tne least

boreal distribution of FM C5 reaches high mountains of Central America arad are best represented

in Guatemala's mountains (Islebe et al. 1995). Several plant communities paye been identued asso-

ciated with bunchgrassland dominated mainly by

,Liulvler.ber,lia ^ruadridenL^!a or Festucn tolucensis.

Rzedowski (1975):eferred te these bunchgrass species, together with C.aL:.niagmstis tolucer,sis, as yen'

abundant associates of Pirms l:artwegii forest.

Evidence of recent buming and grazing (mainly

by sheep) is found in most aseas of this communitv. Wood extraction in central Mexico is practicaliv absent, though in Guatemala ordy a few

patches of this forest remain, due to the intensitv

of fuelwood cutting (Islebe 1993).

,vtixed pine forest. There are a number of large

forested aneas where no single species of pire

seems to be dominant. Such a complex pire unit is

apparently promoted by intensive logging practices and by fire. It occurs in very heterogeneous

landscapes that include flats and steep slopes. Soils

are shaiio'.v, acidic, and sandy. Often, there is recentii, deposited Nolcanic ash or lava (e.g., in the

Paricutín volcano area and other portions of the

Tran versal \eovolcztic Belt). The lava flows hace

en irregular topographv, which produces a diversity of microenvironmental stuations with many

endemic taxa.

Within the 40 m tal) overstorv are Piras nlicimacarsa. P. n:on!e:un:ac, P. lelepi,^ln, P. pseudostrobus, P.

riáis. P. t.'occ:e: and P. iar!:oegi;. A;rus and Quercus

species are present but w-ith less cover than Pinus.

The free canopv is open, more like that of a woodland than a forest. Beiow is en open shrub laver

with Senecto, BuddLfa, Rfbes, and Rubus as charcoteristic genera. The loivest understorv laver

contains Satureia, Stcria, Euyaforium, Salvia, and

cushion-like species such as Arenaría tiroides,

Geranrum seenrar.ii, and r.Id:cn:i!1a p rocunibe?:s. A

defínite bunchgrass laver is absent.

Fir Forest (Abies)

The rnost boreal Mexican yegetation tupe is Abies

forest, variously and locally described throughout

Mexico bv Leopold (1950), Rzedow•ski (1951), Beaman (1965), Anava (1962), Madrigal (1967), and

?,nava et al. (1980). Rzedo•,c ski (1975) has ó ven a

complete description on a natior.al scaie. Fir forests

t ricall% occur helow Pie:-s l:.v! a e;ü forest en high

yolcanoes, along escarpmenrs, and in giens betv een laya floi,'s. T.nec pret'er canyons or other

steep slopes protected from direct sunlight and

strong winds. Soils are rich i-n organic master and

ash.

1hree fir species uccur in Mexico: Abies corcolor,

A. religiosa, and A. gua!rralensis. They usually cooccur in the overstorv with Pimrs, Quercus, Pseu-

582

A. Velazquez, V. Al. Toledo and 1. Luna

Temperate Ve;

i

dotsuga, and Cupressus species. A lower free layer

is comprised chiefly of Alnus, Arbutus, Salix, Prunus, and Garrya species. In rare undisturbed stands,

there is a ground layer of mosses and cushion

plants.

T.he Abies religiosa forest is mainly restricted to

the Transversal Neovolcanic Belt. It occurs on steep

to moder ate (10-30`) outer slopes of volcanic cones

at 3000-3500 m elevation. Soils are deep and there

is a thick laver of Iitter on the surface. Some evidence of disturbance from grazL-ig, burning, loa

ging, and Cree harvest exists (Madrigal 1967; Rzedowski 1975).

The forest is dense and tal], reaching 30 m in

height (Fig. 15.6). The overstory ]ayer is dominated

bv A. religiosa. Below is a ]ayer of shrubs and tal]

herbs (0.5-3 m), dominated by Senecio angal folius

and Roldana barba-jolutnnis , and a ground layer (5

cm tal]) of rosaceous herhs (e.g., Alchemilla procumbens) and mosses (e.g., Polytrichum juniperir:um).

Other diaglostic and common species of this

plant corrmunity group are Ser:ecia toluccanus, S.

eallosus, S. platnn folius, Sihthorpia rrriens, Salix ox;leps, Festuca amplissima, Alchemi!!a procun:bens,

Thuidium delicetvlum, Acaena elongata, Stachvs species, lolium species, Galium, aschenbc nif, Cinna poc:e;ormis, Pernettya prostrata, Dydimaea alsinoides, and

Buddleia sessilijora. At lower eievations Chis forest

mixes with Mulilenbergia and Calamagrostis grassland and A!rus ^5rm,fotia forest (Velázquez and

Cleef 1993).

The Abies guatemalensis forest is mainly restricted to the southernmost part of Mexico and

into the Guatemalan mountains (Islebe et al. 1995).

It occurs on verv steep slopes at 2500.3900 m on

deep soils rich in organic matter (Islebe and Velazques 1994; Islebe et al. 1995). It is a dense forest

with three layers: an overstory fir layer 30 m tal¡;

a shrub layer dominated bv Roldana barba-johannis

and Tetragyron orirabensis; and a moss layer dominated by Thuidium delicatulum. Ot-her species present in this forest include Fuchsia microphy:'la, Senecio

callosus, Trifollunr amabile, Sabazia piretorum, and Pinus '

l n Mexico, there are no communities where

Abies concotor, the other fir species, is dominant. It

alwavs occurs mixed with ponderosa pine. At Sierra San Pedro Mártir, in Baja California Sur, Pinus

ie eyi coexists with Abies concolor as part of other

mixed forest communities (see chapter 5 of this

volume).

Alpine Bunchgrassland

Mexican alpine bunchgrassland is dominated by

tussock grasses restricted to steep volcanic slopes

at elevations aboye timberline (ca. 3800 m; Fig.

15.7). It has been studied by a large number of researchers throughout this centurv (Standley 1936;

Beaman 1962, 1965; Cruz 1969; Delgadillo 1987).

Beaman (1962, and 1965) called this vegetation "alpine prairie ," w'hereas \ 8randa and Hernández-X.

(1963) related it to .-ondean ecosvstems and called

it "high páramo." Almeida et al. (1994), however,

believed that the urique composition of Mexican

alpine regetation mide it different from the actual

páramo. Rzedowski (1975), in ap eement, treated it

as a separate vegetation tupe, which he called "alpine zacatonal."

Alpine bunchgrassiand cornmunities occur in six

main high-mountain formations: Cerro Potosí, Nevado de Colima, Nevado de Toluca, Sierra Nevada,

\4alinche volcano, and Pico de Orizaba volcano. No

svstematic survev has described asid compared

these communities. Recent surveys conducted at

Popocatápetl (Almeida et a;. 1999), lztacdhuatl, and

Nevado de Colima voicanoes rrovide a li-nited

surrunarv cf Mexican alpine ecos%stems. Near the

low'er lirnit, in tse }ic t of Pinus hart-u'egii forest,

Lupinus mo':,anua, Festue. tchrcer:=.., Calamagrostis

tohucensis, Per:aten=ion gentirnicdes, and Descarair:ia

impatier:s are the mest common species. These are

considered the diagnostic species of zonal alpine

communities . Arrizaría ovoides and Juniperus monticola tvpify the azonal aipLne cornrnunities. Near the

upper rival bordee mosses and lichens do=ate

(Bartran :ia and B: roe✓throphyl'urn). Intensive grazing asid fires are fast depleting these alpine ecosvstenrs . Tris vege:aticn also harbors a large number

of ende:rvc taza. Des ite the smail area covered bv

Mexican alpine b unc'r.gr-ssland (0.02% of the whole

countrv), five zonal and b.vo azonal plant associations (sensu Braun -Bianquet 1951) have been described by ALmeida et aL (1994).

In the southem mcuntains of Mexico, at the bordar with Guatemala, diere are smail patches of alpine grassland dominated bv Lupinus mortanus

asid tussocks of Calamagrosts culcar,ica up to 1 m

high. There is ¿!so a ground '-ver with mosses

such as Breu''elia asid L ptoda:ti;an. Other cornmon

species are Luzula -acrorosa , Agrostis telucensis.

Draba r:dcanica, Arrn.:r.'a b soldes, Graphalium srliiciloiium, and FoL^::,•i; (a ;cteresep-ala. On rocky outtcrops, Raccmitriunr ^ü?;dum is dominant. This

southem alpiste kege:ation grow s on gentle, winiprotected slopes wüh regosois (Islebe and Velázquez 199:).

Fire and grazi:g are the majos causes of degradation of alpine bunchgrassland ecosvstem5 \1'hen fires are frrq.:eni, Lupi r.us rucrtanus becores

dominant. Hiking pat5 significantly fragment (:sisa

vegetation (Almeida el, al. 1994).

F..gure 75.6. ,..spe

and 1. Luna

Temperare Vegetation oí.

Iexico

,00 m; Fig.

r; her of re1936;

délo 1987).

don "al.. ,f:ndez-X.

i d called

of Mexican

.:he actual

r+ treated it

"al.Cctr in six

Potcsí, Nevnra Nevada,

vc lcano. No

3 ccmpared

cnducted at

ccir^atl, and

e a limited

ns. Near the

upe; i forest,

C:„-:arr:ag ros!is

Desnrra:ina

es. These are

zonal a!pine

F cure 15.6. Aso ct ol irt ;crest at Ajusco vo'cano 3 , 1OO.m).

..es. Near the

ns dominate

.ensive grazLne ecosys-

rge number

a covered by

of che whole

,!ant associa;ce been de-

:o, al the bor:at&es of al:+;arta,:us

uptolm

.,ith mosses

roer common

to!ucetsfs.

.a!iurn salir, rc+.KV out-

,ant. Ihis

:entre, :cindand Veláz-

❑ ses of dei

ecosystems.

: us becomes

:ragment this

Figure I5.:. Aspect oi alpine bur,chg ^zssland at Izraccihuad cclcano (4i0O m)

583

584-

Subalpine Bunchgrassland (Festuca

tolucensis)

Ibis community is mainly restricted to the fíat valley bottoms within vokanic craters at 3500-3550 m

elevation. Soils are very deep and nave a thick surface ]ayer oí litter. The community consists of a

dense layer oí bunchgrasses 50 cm tall, doninated

by Festuca tolucensis and Cnlan;atirestis to'ucensis.

and an open ,round layer dominated bv.A7dumilla

procun:bcns. Other diagnostic spectes are Poa annua.

Trisetum spicatum, Pinus mnr:fe_u:rae, Pinas

gii. Mu'ilenbergia quadridentafa, Muhienbergia aff.

yusiha, Oxalis spp., Sicvos yar;i.`,on+s, Potent:lia

stanunca, Pedicrdaris ori_abae, Draa iorullensis, and

Arenaría brvoides.

Beaman (1965), Cruz (1969), Rzedowski (1975),

and Almeida et al. (1994) have observed this community in volcanoes along the Transversal Neovolcanic Belt where continuous buming and erazing disturhances take place. This is che reason these

authors considered this grassland to be a seral

communitv (Velázquez' 994). \Coodcutting could

promote this t\-pe oí vegetation.

Less Common Communities

Megarosettes oí Furcraea beding'rausii indicate a

vegetation upe restricted to the rolling , disse ted,

rocky lower slopes oí a few volcanoes in central

Mexico, such as Pelado (3090-3340 m) and Tláloc.

Soils are shallow, gravelly, loam.v clavs (pH 5.36.5). Half-meter - high monocauiescent agavaceous

me,arosettes oí the endemic F:;'aaea be.'ingluusü

characterize this community . The maximum height

ever measured for Furcraea is 53 m. A f oristiallc

rich out relatively open herb :aver is common.

Other characteristic species incude Senecia angulfolius, Stipa tchu, Sympharicarpos mfcrophvllus. Conv=a sciriedeana , Muhlenbergia n:a:rcura, M. quadridentata, Geranium poterrtiliacfo :.m, Gr:aphalivnt

on+yi:vi!u!u. AIchenrilla procunbens , Sibiharpía reyens,

and Festuca an: vtissin!a.

Stipa ici:u meadow is cornmonly known as a

"pradera" oí Potentüla cand ;'eans. It occurs on

poorly drained soils (Cruz 1969 ) cn flats surrounciing volcanic cones at 3000 -3300 m elevation. it is

restricted to the Valley oí Mexico (Rzedows)<Jand

Rzedowsk: 1975; Rzedowski 1981 ). Soils are deep

sandv loaras oí pH 5.G-6.2. Vegetation i s a single

ground laver (0.15 m height ), consisting oí lo,.v

forbs and grasses. Diagnostic and associated species include Stipa iclm. Potentfila ;n:dita; ,, Ast•

alas micrantlrus , Reseda 1uh'ola, 3idenc triylfi:er.'ie,

Hedeonra yipen!¡tut , Con:meiina alpes!n s , Vulpta myures, Akl:emilla procumbens , Gnayrv!i:mt seemannfi,

A. Velázquez, V. Al. Toledo and 1. Luna

and Salria species. This vegetation is significantly

disturbed by hikers and campers.

.An alpine scrub oí Jumpen:s manticnla, codominated by Tortula andico!a, E:3ngiam prctútlorum, and 5enecio n;.ciretfar:us, is restricted to rocks,

wet places aboye timberüne on most high Mexican

volcanoes, such as Po, oca tépetl, and it is also present in Guatemala (islebe and Velázquez 1994).

A narrow ecotonal Cupressus lusitanica forest

used to be widely common behveen fir forest and

cloud forest at about 2600 m eleyation. This transition has largely been deforested and transformed

finto farmland. In the feto remaining patches, Abies

is sometiines co-domLnant in the overstorv. 5enecio

piata,nfoiius, S. cinc arioides, Fudsia ndcrophvia, and

species oí Rubus and Rifes are common Ln an understora shrub layer.

BIOGEOGRAPHIC HYPOTHESES

Mexico's larse biodiversity has been attributed 'o

hvo mala hvpotheses. First, its geographic location

- where t.e Neaaic and the Neotropical zones

overlap - necessar ilv ,laxes temperate and tropical

elements. This is tl e dispersal h}pothesis. Additionaily, a substantial proportion of the total flora

oí ibis region is oí autochthonous origin, fo,nnLng

a heterogeneous mosaic oí species (e.g., Rzedowski

1978). 5econd, its role as a Pleistocene refu,e could

make .a':zeodv-nzrc events oí paramount importance la gocen.rg present vegetation (Toledo

1952 ).

T.ne dispersas hvpothesis imagines that the major mountain ran_es mned as bridges connecting

Mexican and North American .-oras. As a consequence, Holarctic taza reached Mexico across these

:nountzin bridges,.vhich provide a con:inuoaslc

similar climatic condition across latitude (e.g.. Graham 1972; Rzedowski 1975E The arrivzl pernnad oí

most boreal e!ernents is controversial: So:ne authors believe that it -,vas in the Ter;iarv and Early

Quatemary (Graham 1972), whereas Martín and

Harrell (1957), among others, suggest a ¡,lora recent arrival. Tne lose affinity behveen Mexican

and North Amerian temperate taxa has been commented on by severa! biogeographers (e.g., Islebe

and Velázquez 1994). Pczedo•,vski (1993) estimatei

the afíinit<• at 9f at ;`. aeneric 'evel and named

it the "nlega:nexice p :: ie,eograp ic unit."

According to Toledo (1976), hvo aneas of \fevice

functiened as Pleistocene refugia: the Lacondona

and Soconusco regio-s, both oí rvhich still harhor

a larse number of endernic specie s and subsp2c e`

Toledo also hopo;he>ized that additionol reos in

Guatemala and Belize sen-ed as refuges and tr`'t

collectively thev plaved this role several times dar'

. Temperare

ing the Qua

oí glaciers

present dise

vegetation.

There ar

(1952), for ,

between bic

convergent

extend bici

geograpv/-,

rente (1993)

DYNAMIC

Indigenous

tlers, and ci

tures all h;

!andscape.

ulation abo:

oí pre-corta

to rely on

Hemandezgeneralsucc

malnir,g Inc

a, d maintai

Ta: ahumara

1994). There

that suggest

colonial tim

tation couid

stand-replac

(Islebe e: al.

Bv the ti

1500), most

covered by

%Vhen wood

demands (

cvere clear-c

and near lar

sume extent

However, lo

creasing ove

tun•, expiain

forestexcept

Livestock for

tended finto

human pop

needed, and

popular me,

grazing prac

oasis througiledo 1955). A

mote regrow

dental canc

(Velázquez 1',

Most rece

d 1. l;:na temperate Ved

(0:.?, coto rockv,

\texican

pros- 94).

fc-est

etation

in, the Quatemarv. The expansion and contraction

of g)aciers mav additionally have modified the

present dstribution of temrerate humid montane

vegetation.

There are also alternative h•,potheses. Croizat

(1982), for example, finds a ciose correspondence

behceen biologic and geoloo:c histories, suggesting

convergent evolution aad vicariant patterns that

extend back across longer periods. The panbio,eegrapv/vicariance ideas of Espinosa and Llorente (1993) extend back to Laurasian time.

DYNAMICS OF VECETATION

-,b.,t d to

ic location

ica1 zones

..: cpkal

Addia! flora

forming

'.ze ow'skl

-_. e could

_ct imporn (Toledo

.aat th.e m

onnechrng

.s a consecross these

7..ti-:m.:ously

(e.g., Graperiod of

Sume auand Eariv

'aren and

more reMexican

roen cem-

?.,., Islebe

estlmated

named

ot,\fexico

acondona

`arbor

•,:bsoecies.

al arcas in

> and that

times dur-

Lndigenous Indians, contact-period Spanish settiers, and current mixed pepulations of many cultures all base modified t.e temperate Mexican

landscape. There is ve:v little published speculation about reconstruct-.e maps or descriptions

of pre-contact landscapes. Largely we have had

lo rely on experienced botanists Miranda,

Hemandez-X., Rzedowiti, Madrigal) who infer

general successional pathr..avs, and ora t-he ferc rem.aining Lidian groups _^a. _tia manase vegetation

.ai.tain sera] stages mar cultura! reasens (e.g.,

and m

Tarahumaras, Purépet'ras. TzotzLes) (Toledo

1993). There is some evidente from : ellen analvsis

that suggests that there l :as deforestation prior to

colonial times (Metcalfe et al. 1991). The deforestation could perhaps have been caused by large

stand-replacirg tires prornoted by drought periods

(lslebe et al. 1995).

By the time of -he am; al of the Spanish (ca.

L0 ), rnost arcas in central \fexico viere densely

covered by forest in di.`fere.-d successional stages.

when woodcutting took pace to fuif311 European

demands (_ 1700-1500), most temperate forests

were clear-cut on p!ateaus, valleys, around lakes,

znd near larse human se:t!ements. Remaining, to

some extent, vas montane temperate vegetation.

How.+ever. Jogging in montare arcas has been mcreasi.g oven the past 50 vr of the hventieth centurv, explaining the present ratchiness of montane

forest except in the highest, most inaccessible arcas.

Livestock foraging in the nrieteenth centurv extended finto tírese moun'.a..e envi:onr,ents. N'ith

human populatior increase, more meat vas

needed, andburning in t:-.e dn' season became a

popular rnethod to increase forage. This tregrazing practice is still i nlemented on a veariy

bass throughout most of ;Fe temperate rcgion (Toledo 1988).Although the tres are intended to promote regrowth in the understorv vegetation, accidental canopy tires frequently take place

(Velázquez 1992).

Most researchers (Miranda and Hernández-X.

oi

Vexico

585

:963; Madrigal 1967; Rzedowski 1978; Velázquez

and Ceef 1993) agree that fir forest s the mesic

climax tape of Mexican temperate ecosvstems (Fig.

15.S). Ahies co:nm'unities are favored by soils rich

in organic matter, humid terrains, and middle to

high elevations (Madrigal 1967). Clear-cutting for

paper production rransfo-ms :hese forests Lato subalpine bunch rasslar.ds dominated bv Mularrhergia, Calanwgresfis, ard Festuca; selective cutting

trzrsforns them into mixed oak forest w•ith manv

svmpatric Qaercus species. Fire and grazing may

then degrade subaipine bunchgrasslands Lnto a

scrabland of Senecio and Ribes, or roto meadows of

Fofertilia and Stipa rrhere soils are poorly drained.

Scrub and meadow mav regenerate into conifer

forest if there s not stror.g human interferente

(Fig. 15.5). Mixed oak forest can develop finto

mixed alder-oak forest and traen finto either cloud

forest (given sufficient moisture) or hito mixed

pire-aider 'orest (where soils are sandv and

acidic). Mixed pine-alder forest is 'he most w'idely

distributed \Iexican temperate ecosvstem at this

.ir.e. Pire and grazig favor pine species, transfcrmLne tris vegetation tape finto p•ure stands of

pi— forest (Pf s harrargi at Mgh elevations).

Mixed pire-aider forest mav, under very- limited

G: camstznces, develcp back finto fir forest (Hg.

15.5). This happers, for instante, in ver, humid

canvons with a thick litter la%er and an absence of

F:e and erazing. Puse pire forest can also be repiaced by fir forest but only at elevations where fir

species are better adapted tiran unes.

High-elevaion fir and pLne forests, when harvested, revert to alpine bunchgrassland dorninated

by Ca'armgrostis, Trsetum, Agrrstis, and Festuca.

\'exican alpino b•.:nchsrrassland, as well as the

tropical alpine gra stands of páramo and puna, expand where deforestation takes place (Baislev and

L-atevn 1992). Forest regeneration is suppressed =y

E:e- and grazing aovi^es.

Nearnal! temperate vegetation !upes of Mexico

are in some stage of regression or progression. Fire,

srazLng, wind, herbivon-, avalanches, landslides,

volcanism, and human disn:rbances are the causes

o-` tnis seral lancscape. Natural tire and arson may

be the most cornmon disturbznce<_ as evidenced by

t'-. e charcoal that is found in most soils throughout

\`.exco's :nountains. At retum Lntenals of 20 vr,

tire seerns to be a suitahle tool for forest management, but in central Mexico tires recur everv 1-5

vr. Only a few places have remained unbumed >5

vr. The reason for frecuent buming is that the forage becornes less palatable .`or domesticated animas ove, time. A larse amount of oxalates and

siliates, which accumulate in the leaves oí grasses,

may be the cause of low consumption of forage

A. Velázquez, V. Al. Toledo and 1. Luna

586

Vpine

bunchgassland

Cool

bdgh e^eaa ^. o.^s>3:00 n)

Fir forest

Mesic clima

wz.. chesmider:.;n•n_.e.,s

Oow re'va^ov cial:_)

Cloud forest

Figure 7 5 . 8. Sche natic summay of successional relationshios among Mexican temperate vegetaron tvpes. Mesic

climax rypes are s,haded darker than sera! s:ages . Thick arrows represen: natural, progressive succession , v.hereas

hin arrow5 represen: re:rogreirre success,on caused by

human in:e.nerence or by azora1 en, úonmental cond7ons.

(Velázquez 1985). Peasants who set fires, however,

are ignorant oí the fact that many nutrients released by the fire are leached and eroded awav.

Mexican temperate and tropical forests have

been more impacted, fragmented, and depleted

than anv other vegetation tupe (Toledo 19SS; Masera et al. 1992). Recent estimations by Masera et al.

(1992) are that fires (49%), livestock production

(28%), and agricuiture (16%) are the main causes

oí the depletion oí tem orate forests. How+'erer,

these estimates are based on onh• general field obsenatiors and anecd3tal comments from rural

people. Lntensive Jogging activities r+'ere common

Lhroughout the coun-r 30 vr ago. These activities

became regulated by la:v in the 1950s, although ac-

Those few mavs oí current Mexican vegetation

that have been published (e.g., Leopold 1950; Miranda and Hernández-X. 1963; Flores, Jimenéz,

Madrigal, Moncayo, and Takaki 1971; Rzedowski

1978) rapidly became out oí date as extensive human modification oí the landscape continued. Consequentiv, these maps should be considered as depicting potential vegetation ra:.her than actual

vegetation (Velázquez and Cleef 1593). Accordir.g

to Masera, Ordonez, and Dirzo (1992), temperate

forest deforestation (excluding doud forest) has

been estimated at 163,000 ha yr , equivalent to

O.Jl°b oí the total Mexican surface being deforested

every vear. In contrast, reforestation has been attempted en only 13,000 ha, and no: all the attempts

have been successful.

tual imp'.ementation oí :he regulations ,as limi:ed

to central Mexico. ^,e ,+'estem and eastern Sierra:

Madres are stil] beng clear-cut where the original

forests remain. Clcar-a;t;ing in Mexico is net followed bv reforestation; consequently, the neoztiv e

effects oí soil erosion and se¡¡ poductiviry are

astordshing.

Temperate Ve,

In contrast

as practiced f,

favors both re

trees. Minnicf

repeat aerial

have had a s

Aguascaliente

oí Aguascalie.

ests (Quercus :

roxvla, Q. rugí

rus deppeana) t

slopes oí barr

(Fig. 15.9). Ch

pungens, with

opensis, Garrea

abundant on

exploitation fc

using rudimer

tse 1920s dese

Repeat aerial t

1953 reveal th

pulse of wood

oline sawntills

1950 when dic

with the introc

the city oí Ag:

in exploited fe

from pollardir

broad-scale th_

by rapid incre.

establishment

change in the 1

declines in Pin:

attack c ring a

(Siquéir,,s-Def

chaparral expe

fires behyeen

to resprout or

lings from seec

geners in Caii

with open-rang

Recent direc

caused bv anor.

disn:rbance in

derstory in pv

frequent Ere pr.

species of Que'

fires v: ith modo

an ability to r

fines mav have

and encoura2ec

characteristie In.

United States (s

reduce the exte

S!aphylos punge'

aedo and 1. Luna

rcession caused bv

'ro.^.n]e0taf condi-

pical forests have

red, and depleted

Toledo 1988; Masby Masera et al.

estock production

e the main causes

forests. However,

general tie)d obments from rural

ries viere conunon

:o. These activities

i930s, although ac>tions esas lir ited

and eastern Sierra

i,here the original

Mexico is not tolently, the negafive

productivify are

587

Te.rperate Vegeta:ron of Mexico

Ln contrast, less intensive fue!w.wood gatr.ering,

as practiced for local consumption by rural people,

favorsboth re;eneration and de%elopment of adult

trees. \finnich et al. (1994 ) provide evidente from

repeat aerial photographs that land use mav not

have had a severe impact on pine-oak forest in

A uascalientes. The Sierra Fria, located in the State

of Aguascalientes , is dominated by pine-oak forests ( Quercus potesi na, Q. lacta, Q. eduardii, Q. sidermaa. Q- rugosa, Pinus teocore. P. leiopltylla, Junfpcru; de}>peann ) that forro contiguos forests on steep

slopes oí barrancas, and open savannas on mesas

(Fig. 15.9). Chaparral dominated by Arcto;tcphvlos

pun ens, with scattered Arburus glandalosa , .4. ralcpe:ss, Garrua spp. and Conreresta^ )rylos poiifclia, is

abundant on steep slopes . Technologies for forest

exploitatien for rirrtber and charcoal production,

using rudimentary ground kiins , viere limited until

the 1920s due to the inaccessibcity oí the range.

Repeat aerial photographs taken between 1942 and

1993 reveal that the range experienced a distinct

pulse oí woodo.:tt ng with the introduction of gasoline sawrnilis alter 19-0. This iand use ended in

1950 when the urban demand íor ;uelwood ceased

with the irtroduction oí ural gas pipelines into

the city oí Aguasca lientes. Oaks viere still common

in exploited forests because most species resprout

from pollardinz . Since 1942 there has also been

broad-scale thickening of pme-oak forests caused

by rapid inaeases of Jurti?er s dc,,peana and slow

establishment o: Qucrcus spp. There has been little

change im the dstrbution oí pues except for local

declines in Pms:eiephvüa and P. teocote from insect

attack during en El Atto-related drought in 19S4

(Siquéiros- Delgado 1989 ). Ardo;taphylos pr jenn

chaparral experienced little change in spite oí largo

;res betweer, 2920 and 1950. Most species appear

to resprout or to establish numerous postf:re seedlings from seedbanks (A. punge'a), similar lo congeners in California. Stand-tnickening ceinc`ided

with open-range cattle grazing.

Recent direcvona: vegetation changes mav be

caused by anoma )o'as)v infreauent Eire as a natural

dist'srbance ir' the siena . A dense )erhaceous understorv in p--e-oak forests probably supported

frequent fire prior to livestock grating . The cariors

species oí Qurc:is are adapted to sunive ground

tires with moderately thick bark, tal1 canopies, and

en ability to resprout from rootcrowns . Surface

tires may hale selective : v c'Iimtnated yni2ng Fines

and encouraged open o':d-growth forests, as esas

characteristic in cellow pire forests in the western

L'nited States (see Chapter 5). Recurrent tires mav

reduce the extent oí Juniperus deppeana and Arctostaphylos pur.gens because thev are nonsprouters

and do not establish abundant postfire seedlings

from seedbarls. J. dcpra :a mav have survived in

Eire-protected camyers where old-growth stands

no occar.

Urba:-tization v perhaps the most threatening

human aCivity lo temperate forests in central Mexico. Mares oí the maro urban concentrations oí the

co^untrv, includv,g Mexico City, are located in (or

near) temperate vegetation. According lo the National Censas oí Population of 1990, the area covered by temperate vegetation s inhabited by about

19 ,—n people, or one quarter oí the total Mexican

population (Toledo and Rzedowski 1995). Oí these

"•temperate" people, 62% live in cities and 3S°'o in

che co,:ntn-side. It is Chis latter nonurban population oí approimateiv 7.3 million who live most

int mately with temperate vegetation. We estimate

that t`re precortact population within temperate

veeetation „as - in contrast - only about 2 m indigenous people belonSing te 40 different ethnic

groups.

CO.NSERVATION IMPORTANCE

AND PROBLEMS

The tisea ecological regions that constitute the

temperate vegetation area oí Mexico are oí great

portante from a biodiversity point oí view. Despite its reiativ ely small area , t're humid temperate

cioud forest is bioleg caUy very rich. lt harbors a

large number o.` endemic plant species, especially

orchids, ferns, and mosses. Given the small area

and tie lar,e nwn:ber of specíes, it is floristically

the richest zone it \!exico bv unit area (Rzedowski

1993: Stvles 1993). The zone is notable as well for

its lar_e rumbee oí endemic mammals, amphibians, reptiles, and butterfiies (Flores 1993; Flores

and Gerez 1994) lo such an extent that it is one oí

ihe ^ncipal centers oí autochthonous species. Areas abone timberline (>4000 m) are also oí notable

biolc r) and biageog aph cal importance.

O'•erall, the temperate zone covers the greatest

p¿-:t oí the -nountainous arcas oí Mexico. Of special impon tanto s ;.he Transversal Neovolcanic Belt

hecause it harbors one of the highest concentratiors c` specíes dicersity and endemism presentiv

kno-t.-n (Fa 1959). Rzedocski (1993) estímates that

there are 7000 specíes oí flowering plants, oí which

49',J (ca. 75%) are endemic.

About 7.3% of the Mexican territorv is under

sonx po ic} oí protection (Flore; and Gerca 1994).

T.ne criteria for the selection oí protected arcas and

their boundaries hace changed from time lo time.

Most protected arcas (79 out oí 1660) are within

the temperate region and harbor temperate vege-

588

A.

Velazquez,

V, Al. Toledo and 1. Luna Temperare Veger

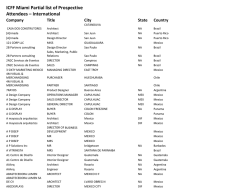

Figure 15. U Defortional Park 11,900 m'

heede !Dendroctonu

cation tepes (Fio(

naulative area is

al] protected area

surface. Most of th

'egetation are %-e.

that the probabilc

into the future s

trolling to reduce

croachment is lim:

pects nave been ta:permanence and c,

com 1994; Toledo

ÁREAS FOR

FUTURE RESEAR(

Figure 75.9. Pine-oak ioresi in me Sierra Frs. A,aasca- and savannas. 31 Tvpical trr cure ui ti:e ,ore>c., ood!."' `

tientes. (A) General aspect, sho.+irg mosaic oi v: oodlands

;Photographs Couiesy oi Richa:d htinnioh.l

Temperare cegetati

mous impon Lance

They also have ccc

Portante as sources

ceutica's, water, erc

rent knowledge is.

^lest studies ha\ e c:

munities in Central

d 1. Luna

Dresd,voodlar.d

589

,emperare Vegeta don oi A7exico

Fisure 15.70. Deioregytion :n Desierto de ¡os Leones xa:ionai Park 2900 m7 near M exico Ciry, caused bv bark

beet!e rDendroctonus adjuntes!. Air colutants initially

}, eakened :he ,ores:: inrestation by bark beedes then

caused the death or 15%% oí me «ees.

tation tupes (Flores and Gerez 1994), but their cumulative area is modest, accounting for only 4% of

all protected area , or oniv 0.32% of the Mexican

surface. Most of the protected areas witi^ temperate

ye etation are verv small in sine, which implies

that the probability of their cor.tinued existente

roto the future is low. Financial support for patrolling to reduce poaching and other human encreachment is limited. Furtherrnore, no social aspects have been taken finto account to ensure their

permanente and consen'ation (\IcNeely 1989; Alcem 1994; Toledo and Ordoñez 1993).

i-^ormatien about northem and southem communities. In addition te the need for mere descriptive

studies, ;reat effort should Se given to docurnenting ecosvstem processes such as vegetation dynamics and succession. These ecosvstem processes

are the least known aspects of temperate vegetation. The ¿ata are needed to model funare distributions and compositions of these communities.:f

Esancial sapport vvere available, such data could

be obtained re!aüvely quickly. In the absence of

supporz, the most feasible future of tmperate

piant comrnunares is their progressive destruction

(Fig. 15.10).

ÁREAS FOR

FUTURE RESEARCH

Temperate vegetation tepes of Mexico hace enormous importarte as resenvoirs of biodiversitr.

Thev also have economic and hum: n ! calth importance as sources of timber, fuel•.vood, p'r-armaceuticals, water, eroson control, and oxygen. Current know:edge is, hor+ever, far from complete.

Most studies have concentrated on describing communities in Central Mexico, leaving larse gaps in

REFERENCES

-„mrn. 1. 3 . 159,. Noble savage or noble state ?: northem rnvt s ard southem realities in biodiversity

corlen ztio.-.. Etnoiecoloo cz 11:1-3. 4ou:!cra, `. , T. \f. Do,,. and R. Hcmándcz S. 1961

Suelos, problema básico en silvicultura , pp. 108-140

Lo Seminario y viaje de estudio de coniferas latirozrnericmzs. lns. Nac. Lnvest. Forest Pub]. Esp. 1.

México, D. F.

Airneida, L., A. \I. Cleef, a. Herrera , A. Velázquez,

and 1. Luna. 1994. 1994 . El zacatonal alpino de]

590

A. Velazquez, V. Al. Toledo and 1. Luna

Volcán Popocatépetl, México y su oosición en las

mallan biogeography in the Trans-Mexican Neovolmontañas tropicales de América. Phytocoenologia

canic Be!t. Nat. Geog. Res. 7:96-315.

22:391-436.

Ferrusquia-Villafranca, 1. 1993. Geologv oí Mexico: a

Anava, L A. L. 1962. Estudio de las relaciones entre

smopss, pp. 3-103 in T. P. Ramarnoorthv, R. Bve,

la vegetación, el suelo y algunos factores climáticos

A. Lot. and J. Fa. (eds), Bioiogtcal dlversity oí

en seis sitios del declive occidental del Iztacc,nuatl.

\íexico (origirs and distribution). Oxford UniverTesis. Facultad de Ciencias, LXAM. México, D.F.

ssity Press, Oxford.

Anaya, L. A. L. S. R. Hernández, and S. X. Madrigal.

Flores, M. G., J. L. Jiménez, X. S. Madrigal, F. R. Mon1980. La vegetación y los suelos de un transecto

cavo, and F. T. Taka)J. 1971. Memoria del mapa de

altitudina! dei declive occidental del lzacc--Jiuatl

tipos de vegetación de la Republica Méxicana. Se(México). Boletin Técnico 65. L\iF, SARH. Sléxico.

cr etaria de Recursos Hidráulicos. México, D. F.

Balslev, H., and J. L. Lutevn (eds.). 1992. Páramo. AcaFlores, 0. 1993. Herpetofauna oí \!exico: distribution

demic Press, New York.

and endemism, pp. 233-280 in T. P. Ramamcwrthv,

Beaman, J. H. 1962. The timber!ine oí iztaccrhuatl

R. Bve. A. Loto y J. Fa. (eds.), Biological diversity oí

and Popocatépeti, México. Ecologv 43:377-355.

Mexico. Oxford Urcersih' Press, Oxford.

Beaman J. H. 1965. A preliminarv ecological study oí

Flores, O., and P. Gerez. 1994.'Biodiversidad y conserche alpine flora oí Popocaténeti and Iztacdh::atl.

vación en México: vertebrados, vegetación y uso

Bol. Soc. Bot. México 29:63-75.

del suelo. UNAM - CONABIO. México, D. F.

Beard, J. S. 1944. Climax vegetation in tropical America.

Gadow, H. 1930. Joruilo: The histon' oí the volcano JoEcoiogv 25:38-125.

rito and reclamation oí the deyastated district bv

Beard , J. S. 1955. The classification oí tropical American

animals and Cfanti. Cambridee Uriversity Press,

vegetation types. Ecologv' 36:89-100.

Cambridge.

Benítez , B. C. 1985. Efectos del fuego en !a vegetación

García, E. 1981. MocfScaciones al sistema de clasificaherbácea de un bosque de Pir:us harta':\;i Lindl. de

ción de Koepper.. la. Edición. instituto de Geograla Sierra de l Ajusco, pp. 111-152 in E. H. Rappoca, Universidad Nacional Autcroma de México.

port, y I. R. López Moreno (eds), Aportes a la eco!México, D. F.

ogía urbana de la ciudad de México. Editorial LiGarcía, E., and Z. Falcón. 1556. Nuevo Atlas Porrúa de

musa, México.

la República 7a. edición. Editorial PorBraun-Blanquet, J. J. 1951. Pflanzensozioloeie, Grundrua, S. A . México.

züge der Vegeationskunde, 2nd ed. SpringerGoldman, E. A., and R. T. \loore. 1945. The biotic provVerlag, New York.

inces oí Mexico. j. Mammal. 26 3.47-360.

Breedlove, D. E 1981. Flora de Chiapas. Par-, 1: LntroGonzález, J. G. 1982. El Volcán el Pelado como una

duction. California Acaderny oí Sdences, San Franreserva natural. Tesis. Facultad de Filosofía y

cisco.

Letras, Colegio de Geografía, ENAM. México,

Cervantes, F. A. 1980. Principales características biológiD. F.

cas del conejo de los volcanes Romrola;us diazf,

González-Espinosa, M.. P. F. Quintana-Ascencio, N.

Ferrari Pérez 1893 (Mammalia: Lagomorpha). Tesis

Ramírez-Marcial, a-nd P. Gavtán-Guzmán. ]991.

de licenciatura. Facultad de Ciencias, UNAM. MéxSecondary succesion in dispar'-^ed Piaus-Qucrars

ico, D. F.