Immunophenotype of Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

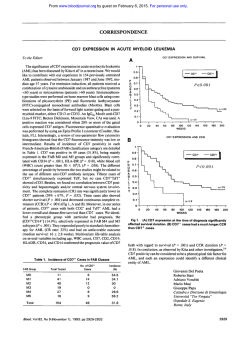

From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on February 6, 2015. For personal use only. Immunophenotype of Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia, Clinical Parameters, and Outcome: An Analysis of a Prospective Trial Including 562 Tested Patients (LALA87) By Claude Boucheix, Bernard David, Catherine Sebban, Evelyne Racadot, Marie-Christine Bene, Alain Bernard, Lydia Campos, Helene Jouault, FranGois Sigaux, Eric Lepage, Patrick Herve, and Denis Fiere for the French Group on Therapy for Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia The aim of the multicentric trial LALA87 was t o test the efficacy of different postremission therapies in adults (15 t o 60 year olds) with acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL). An immunologic subclassification based on surface marker expression was proposed. Among the 562 tested patients, 511 were assigned either to the B lineage (361 cases, 6 3 % ) or to theT lineage (150 cases, 26%). T-ALL were significantly associated with male sex, age less than 35 years, mediastinal mass, central nervous system involvement, highwhite blood cell count, and low anemia. In a univariate and multivariate analysis, T-cell leukemia had a more favorable outcome than Btell leukemia with respective median disease-free survivals (DFSs) of 28 and 14 months (P < .005). However, the type of postremission therapy modifies the value of the immunophenotype prognosticfactor. Inthe che- motherapy arm, T-ALL patients (26 patients) had a more favorable outcome than B-ALL patients (57 patients) ( P < .003). In the autologous bone marrow transplantation (ABMT) arm, the apparent better outcome of T-ALL patients (35 T/50 B) did notreach statistical significance ( P = .2) and there was no difference in the allogeneic bone marrow transplantation (alloBMT) arm (37 T/71 B: P = .g). In the B-celllineage leukemias, subclassification by stages and myeloid antigen coexpression (109'0) were not associated with different prognosis. CD10+ T-ALL (31 patients) were associated with a better DFS compared with the CD10- T-ALL (73 patients) with respective median DFS, not reached and 18.5 months ( P = .04). 0 1994 by The American Societyof Hematology. T bone marrow transplantation ( ~ ~ ~ O B Mand T autologous )~~.~~ bone marrow transplantation (ABMT).28-30 Only multicentric studies with random assignment and careful analysis might help to define adapted therapies in relation to the diversity of the disease. Patients included in a large French multicentric trial LALA8731were submitted to an initial evaluation including immunological phenotyping. This report describes immunological phenotypic data and analyzes their relationships with clinical characteristics and outcomes. The main objective was to assess the relevance of a reliable immunologic classification with three objectives: (1) to identify a clinical and biologic profile according to phenotypic subgroups; (2) to assess the effect of phenotype on outcome; and (3) to evaluate the optimal postremission therapy in each group. HE RELATIONSHIP between lymphoid ontogeny and human acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) has been more precisely unravelled by the description of the differentiation pathways of the T-and B-lymphoid lineages."8 The sequence of events leading to the development of mature lymphoid cells is associated with cell surface modifications that can be easily analyzed by the use of monoclonal antibodies (MoAbs). The importance of the immunophenotypic analysis of ALL has been documented by numerous studies in adults and children. However, the great number of phenotypic patterns has introduced a further level of complexity in the classification of ALL. If certain leukocyte differentiation antigens used for these analyses show some level of lineage specificity (for instance the CD3 T-cell lineage), other surface molecules display a wider tissue distribution. For instance, the CDlOKALLA antigen initially described in nonTleukemia' and now identified as neutral endopeptidase, has a large tissue distribution, but its transient expression during B-cell differentiation helps to define a particular stage; it is also expressed on a fraction of T-ALL (for review, see Lebien and McCormack"). On the other hand, the myeloid markers CD13 and CD33 have notbeen found on normal lymphoid cells and their expression in some ALL has been referred to as myeloid antigen coexpression. The clinical significance of the presence of myeloid markers has been widely debated,""'but because of the small size of some of the patient groups, the mixture of adult and pediatric cases and the differences in the treatment protocols, no final conclusions can be drawn from studies completed thus far. Beside immunophenotyping aspects, the heterogeneity of the disease is observed at both clinical (age of onset, sex, symptoms, and prognosis) and biologic levels (cytology and cytogenetic aspects). Despite some recent progress, the prognosis of adult ALL remains poor. If complete remission (CR) can be achieved in 70% to 80% of patients, relapses occur frequently and long-term disease-free survival (DFS) does not exceed 25% to 30%.20-25Three kinds of postremission therapy can be proposed: chemotherapy (CT), allogeneic Blood, Vol 84, No 5 (September I), 1994: pp 1603-1612 MATERIALS AND METHODS Patients From November 1, 1986 to July 31, 1991, 634 patients treated in 43 hematologic centers entered the LALA87 trial. Eligibility criteria From HGpital Paul-Brousse, Institut National de la Sante' et de la Recherche Me'dicale, Unite' 268, Villejuif; HGpital Edouard-Herriot, Lyon: Centre Regional de Transfusion Sanguine, Besancon: Faculte' de Me'decine, Laboratoire d'lmmunologie, Nancy: H6pital de 1'Archet, Nice: Hepita1 Henri-Mondor, Cre'teil: H6pital Saint-Louis, Paris. Submitted December 30, I993; accepted April 28, 1994. Supported by an INSERM Research Contract No. 89 69001, RCseau de Recherche Clinique INSERM 488009, and Association pour la Recherche contre le Cancer Contract No. 6763. Address reprint requests to Claude Boucheix, MD, H6pital PaulBrowse, Institut National de la Sante' et de la Recherche Me'dicale, Unite' 268, 94800 Villejuif; France. The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. This article must therefore be hereby marked "advertisement" in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section I734 solely to indicate this fact. 0 1994 by The American Sociery of Hematology. 0006-4971/94/8405-0.00/0 1603 From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on February 6, 2015. For personal use only. BOUCHEIX ET AL 1604 LALA 87 i INDUCTION l I $1 l V I CONSOLIDATION POST-REMISSION THERAPY Allogeneic 116 1 I BMT (+6 > 40 years) +I > 50 years CT INCLUDED 634 CRl ANALYSED 572 __.+ 436 (76%) (15 60 years) ~ JI Relapses 21 BM harvest and purge \ RANDOMIZATION + were morph~logically~~ and cytochemically confirmed diagnosis of ALL (L3 FAB subtype excluded), absence of prior malignancy, severe illness or psychiatric disease, and age from l 5 to 60 years. After exclusions, 572 patients were analyzed. Median age ofthe population was 33 years. The design of the protocol and the main clinical results have been reported el~ewhere.~' The general design withthe flow chart of the patients is summarized in Fig 1. Briefly, eligible patients were submitted to an induction CT regimen including cyclophosphamide, vincristine, prednisone, and a random allocation between two anthracyclins (daunombicin or zorubicin). If CR was not obtained at day 28, a salvage therapy with amsacrine and cytosine arabinoside was administered. A central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis was associated. Patients from 15 to 40 achieving CR, with an available HLAcompatible sibling donor were scheduled for alloBMT. Patients over 50 years received consolidation and maintenance CT. Patients from 40 to 50 years and patients up to 40 without HLA sibling donor were randomized after a first course of consolidation between consolidation and maintenance CT or consolidation and ABMT. They received inboth arms three courses of consolidation including the anthracycline used for induction, cytosine arabinoside and L-Asparaginase (modified 3A protocol). In the CT a r m , the maintenance In the CT consisted of eight cycles of the L10 modified protoc01.~~ ABMT arm, the protocol assumed MoAb depletion of the BM by the MoAbs D66/CD2, A50/CD5, and I21/CD7 (provided by A. Bernard) for T-ALL and the MoAbs ALBZKDlO (Immunotecb, Marseille) and SB4/CD19 (Sanofi, Montpellier, France) for B-ALL. Asta-2 (Asta Werke, Frankfurt, Germany) depletion was proposed for patients with less than two of these markers on their leukemic cells. Stopping date was set for September 1992. Median follow-up was 33 months. Four hundred and thirty six patients (78%) achieved CR after induction or induction and salvage therapy. One hundred and sixteen patients were scheduled to receive alloBMT with an estimated 3-year DFS rate of 43% ? 5%. The ABMT ann (95 patients) and CT arm (96 patients) produced comparable 3-year DFS rates (39% v 32%). Patients over 50 years had a 3-year DFS rate of 24%. Immunophenotype Analysis To classify the disease according to the differentiation pathways and to choose appropriate antibodies in case of BM depleted autograft, heparinized BM or blood samples were used for immunophe- ABMT 95 1 Seattle Grafted 63 Fig 1. General design and flow chart of the LALA87 trial. notyping using a panel of MoAbs. Immunophenotyping was usually performed on BM cells by indirect immunofluorescence and flow cytometry, to analyze a pure (or nearly pure) blast cell population. The immunologic classification used in this trial was based on the expression of the CDl, CD2, CD3, CD5, CD7, CD4, CD8, HLADR, CDlO, 0 1 9 , CD20 markers and the absence of surface Igs. However, it had been suggested that the panel of antibodies tested be extended. Therefore numerous patients were tested also for CD9, CD13, CD24, CD33, and HLA class I1 antigens. Because of the large number of centers involved in the study, the origin of the MoAbs varied from one center to another, butthe different antibodies belonged to the same cluster according to the CD n ~ m e n c l a t u r e .Results ~ ~ . ~ ~ were reviewed, interpreted, and registered in an independent database (with the same entry number as the main database) by an immunologic committee that issued regular information to the centers involved in the trial. After reinterpretation and correction for the blast cell percentage and negative controls, the arbitrary threshold of 20% labeled blast cells was considered the limit for positivity of a given marker (20% blast cells expressing the antigen). If necessary, the immunologic committee requested new testing of the cells with additional MoAbs on cryopreserved cells. The fusion between the complete immunologic database with the main database was performed in January 1993. We proposed an immunologic classification B1, B2, B3A, B3B, TlA, TIB, T 2 , T3, as defined in Fig 2. To reduce the number of subgroups, the lineage assignment was determined by the presence of the pan-lineage markers, CD19 for the B-cell lineage, CDUCDSI CD7 for the T-cell lineage. The level of differentiation was evaluated by the presence of the CDlO and CD20 antigens for the B-cell lineage and the CD1 and CD3 antigens for the T-cell lineage. For the latter, in the absence of CD3 or CD1 expression or in the absence of testing, the presence of the CD4 and/or CD8 markers was considered as reflecting a higher level of differentiation and assigned these patients to a T2T3 subgroup. Classification in intermediate stages or only within the T-cell lineage was decided in the absence of testing of differentiation stage markers. Finally, in cases of coexpression, the most differentiated marker was considered for the classification; eg, coexpression of CD1 and CD3 assigned the leukemia to the T3 stage. Statistical Methods The endpoints were CR rate, overall survival, and DF'S. Survival duration was calculated from the date of randomization until death From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on February 6, 2015. For personal use only. lALA87.IMMUNOPHENOTYPEANDOUTCOME 1605 of differentiation and lineage involvement is shown on Table 1. Terminologies such as B1B2 or T1T2 indicate that one or several markers were not tested precluding a more accurate classification. B-lymphoidlineage ALL B1 B3 I B2 B I I HLA-DR b I CD19 CD 10 CD20 T-lymphoidlineage ALL I I m I I I T1 T 2 I T 3 CD7 CD5 CD2 CD 1 CD4 CD8 CD3 UD = undifferentiated ALL UC = unclassified ALL Fig 2. Classification of adult B- and T-ALL according to immunophenotypes in the LALA87 trial. or date last known alive. DFS was calculated from date of CR until relapseorlastknownsurvivaldateinCR.Deathsin CRwere counted as adverse events. Survival curves were estimated by the method of Kaplan and M e i e Univariate ~ ~ ~ analyses were performed using the chi-squaretestandthe generalized Wilcoxon test of Gehan.38Test statistics for comparison of endpoints were regarded as significant if the P value was < .05. All survival analyses were made on an intention to treat basis. Multivariate analyses of prognostic factors were performed according to Cox's proportional hazard model for covariate analysis of censored survival data.39 45 RESULTS General Characteristics of Immunophenotypic Data B2 36 As shown in Table 1, 572 patients (15 to 60 years old) were evaluable for clinical analysis. Immunophenotyping was not performed in 10 patients. According to our criteria, 51 1 patients over 562 (90.9%) could be assigned to the B lineage (361 cases, 63%) or to the T lineage (150 cases, 26%). Fifteen patients (2.7%) were negative for all markers of the B or T cell lineages, and thus were considered as undifferentiated. Because of insufficient data, 36 patients (6.2%) remained unclassified (UC); in 9 of these patients, the inability to perform a significant immunophenotype could be related to BM fibrosis. The distribution related to the stage Comparative Clinical Analysis of the Major Immunophenotype Groups Main pretherapeuticcharacteristics. Clinical andbiologic characteristics, related to each type and subtype, are reported in Table 2 for all patients between 15 and 60 years old. T-ALL and B-ALL significantly differed in their presentation. Patients with T-ALL were statistically significantly younger (77% of them are younger than 35 years v 50% for B-ALL: P < .00l). Patients with T-ALL were more often male (75% v 55% in B-ALL, P < .001). Mediastinal mass was present in 49% of T-ALL versus 2% in B-ALL (P < .001) and white blood cell ( W C )count was greater than 30 X 109/L in 55% of T-ALL versus 30.5% in B-ALL (P < .001). Anemia was less frequent in T-ALL (65% v 85% in B-ALL, P < .OOl). CNS involvement was observed in 10.5% of T-ALL whereas it was present in only 5% of BALL (P < .04). Relationships between phenotype and outcome. As shown in Table 2 for all patients from 15 to 60 years, global CR rates were 81% for T-ALL and 74% for B-ALL. This difference was not statistically significant (P = .08). For TALL, 106 patients over 150 (71%) achieved CR at day 28 after the start of the induction course and of the 38 patients who received the scheduled salvage therapy with amsacrine and cytosine arabinoside, 16/38 (42%) patients achieved CR. For B-ALL, 248 patients over the 361 achieved CR at day 28 (69%) and among the 68 patients who received the salvage therapy, 19 (28%) of them achieved CR. Patients with T-ALL had a significantly better DFS and better overall survival when compared with patients with BALL. The respective median DFS for T- and B-ALL were Table 1. Frequency of Immunologic Subtypes in the LALA87 Trial BLineage Subgroups CD13 T- CD13 Lineage andlor No. B1 B1 1 B2 142 B283 B3 6 B3A 117 838 14 Totals (63%) 361 CD33' andlor No. Subgroups T 4/36 T1 0 T1A 15/120 T1B 1/18 T1T2 012 2/30 T2 5/97 T2T3 019 T3 251282 14 4 11 27 2 40 9 43 150 (26%) CD33' OB 214 311 1 3/25 012 014 2/32 121117 Of 572 patients, 15 were undifferentiated, 36 were unclassified, and 10 were not tested. The B283 group represents patients not tested for the CD20 antigen; the T group represents mainly patients tested for CD2, CD5, and CD7 but not for the other T-cell differentiation markers. The T2T3 group contained patients not tested for CD3 and positive for either CD1, CD4, and/or CD8 markers. The number of patients expressing CD13 and/or CD33 among those tested for these antigens is also indicated. From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on February 6, 2015. For personal use only. 1606 BOUCHEIX ET AL I I S *LD S N N 1 I % m r I d N ~ N S S I m 0 m 3 f m ; $- 2 c -.g '6 C w - S E N 0 - < " 2 I s r m $i - gm- $ * (D - m "Qz$,E " B p' N d e sh S m I m - $ o m 4 " N W O ~ I " m - I - m S g m F m2 s:+; z 2 m :?m zqall,g z ~ - 2 s Q k - c ? m p 9.- 0 m " ~ m % o + ~ -mm &m mk N m o (D m -d 0 :-c? r (Dl.- s t rn g 5 g -? m G h ~ k r d r a2 .-c D ..-. " -m m m" ( S ru?Sl.%g =--~mR~~$dzwm~~~~~~ m , ~ I p 4 t " N I N a s gE m S u?tu?P J - O h m -r ; $ mg - S z -m z g~z zZZ?azeENa ~z 7 -P 5 h U N O W % W O d r N N E N a g h b z k d N h g r + - u * N - 'C v m N S :, * " 2 ~ o mN $ C~ -~z oQ z ~o gI a c ~m " , I .-c5 d - m o?"s re n~r .b i S mrm 4 (eD m ~ og d=l .~mmmra~N ; Z G p N - N ~ N - N "u?;z; S " $N., S %Nz L z gz , poN z' nmm" " ; ~ " - 2 m m c r P ~ zZ z z N P z " -E r .-cE .-a g c r : .-um u a, o a =.- G m .S - $: 4 r r " d $ 2 N N cE2g L si f =. 8 9 6 9 0 C V I S S I a z.. e - ~ a mg- $ Lo~ 2c9"~- Sg . ,g* $ g az z5o!zR F z .Br "! .P m c r r .e m U A e a Z ' - .- S i z v v v - t- v) 9 9 9 s gg;s r 0 0 0 ?.L ( D .-$ 22 a2 02E U g ; "2 \ i v ' v 6 6 cri g .S .g -5 z :k - 8 0 m 9 2& m 3 6 C - vi ? ,g=m% 6m . ;"a*?hg&g PP N SXmN*? 4 -P m mL Z C z r 3: s N C h - N S 2m ,SE zz:" g m ) z.. ? U B ! i i 4 c - .- 0 c C ? m - € 0 5 d - S - " Q .- Er$+G- "l"5d -s 2 E" -l&zE0 5 % E U - 3 Q gci 3 E m 1 3 g c i .. 9 S E : .pt ._ 2 .5 v) - .S2 2 x, g+ <, .. m*&?, E8 ;:~ gS8g-gzxosSB !&? ? - s .c2E +$? C$k;Oz o m z v m B m a ~ ~ v I ~ ) z Y I Z G P V I S$s Emz E ss 0 ~ z ~ ~ From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on February 6, 2015. For personal use only. LALA87, IMMUNOPHENOTYPE AND OUTCOME 1607 100 DFS 3 ycnrs % montha 0 ** "b.0.. *tt 4.*4*.** 40 52.4 43 T-ALL (N-103) 33.5 15 B-ALL (N-172) pes 4 8: 89(52) DFS 0 . .......... 8.0 b .................. . p "***4..* b Allogmneic BMT ann S 40 p m 9: RCI. N(%) 37(36) 4..*.. 4. - T-ALL (N-37) B-ALL (N-71) months 22 23 3ycan &.l. % N(%) 44 14(38) 45 26(37) p - 0.9 ... ...b . . . . . . ...................... ...................... 0.01 ...... ............... 4 Auto&gvw BMT ann S 40 years % DFS bbb : 8;. .b 0 :6.6. *. T-ALL (N-29) B-ALL (N-38) months n.r. 25 58 . ................................... ......... p b........., i 3ycam % 20(53) 43 Rd. N(%) ll(38) 0.27 I '...... ....................... 2 3 4 5 years p b 0.. i i 3 4 - o.ooo7 5 years Fig 3. T- versus B-ALL DFS curves for patients5 40 years in the various armsof the ALL87 trial. A curve of a11 patients c 40 years is shown for comparison. Patients S 40 years in CR with an HLA-compatible sibling were selected immediately for alloBMT; the DFS stam with the obtention of CR. For the CT and A B M arms, patients in CR were randomized after one cyde of consolidation therapy andthe DFS stam at the date of CR obtention. All statistical analyses were performed on an intention to treat basis h r . , not reached; N. number; Rel, relapses) 28 months and 14 months (P = .005). Respective overall survivals for T- and B-ALL were 25 months and 16 months (P = .001).Ina multivariate analysis, Tphenotypewas found as an independent favorable prognostic factor (P = .W) as well as initial WBC count less than 30 X 109/L (P < .001) for overall survival. For DFS, T phenotype was also found as an independent prognostic factor with age less than 35, initial WBC count less than 3O.lO9/L and platelets greater than 100 X 10'' /L (P < .001). Impact of the phenotype group on the outcome of the drfferent postremission therapies. When stratifying according to the different post-remission therapy regimens(CT arm, allo-BMT arm and ABMT a rm)a statistically significant difference between the outcome of T- and B-ALL was only observed in the CT arm (Fig 3). The relapse rate for T-ALL was identical in each arm, but varied considerably for B-ALL. Among the 96 patients randomized in the CT arm, 26 of them (27%) were T-ALL, whereas 57 (59%) were B-ALL. There was a better DFS for patients with T-ALL, with a median DFS not reached compared with 16 months for patients with B-ALL, and a 3-year DFS probability rate of 59% for T-ALL versus 20% for B-ALL (< .003). Among the 95 patients randomized in the ABMT arm, 35 of them (37%) were T-ALL, whereas 50 (53%) wereBALL. The observed difference favoring T-ALL was not statistically significant (P= .2). Median DFS was not reached for T-ALL, but was 12 months for B-ALL. The respective 3-year DFS probability rates were 51% and 35%. Amongthe 116 patientsscheduled for alloBMT,35 of them (32%) hadT-ALL,whereas 71 (61%) hadB-ALL. The outcome for T- and B-ALL wassimilar with respective medianDFSof 22 and 23months and respective 3-year survival probability rates of 44% and 45% (P = .9). To illustrate the influence of postremission therapy on the outcome according to the immunologic phenotype,Fig3 displays the DFS curves for all patients = 40 years according to the three therapies. Immunologic Subclassification and Clinical Outcome B-lymphoid lineage ALL. Itwas possible to makean accurate assignment, using theclassificationproposed above, for 318/361 of the B-lineage ALL (88%) with alarge majority of B2 (40%) and B3A subtypes (32%). For these 318 patients accurately assigned to a given subgroup of the Blymphoid lineage (Bl,B2,B3), no difference between these different immunologic subgroups was observed in terms of CR rate, DFS, and overall survival (Fig 4). The presence or absence of CD10 antigen did not change survival parameters.Myeloidantigen coexpression CD13 and/or CD33 was examined in 282 of these patients; leukemic cells of 25 patients (8.9%) were positive for at least one of the two markers. CD13 was observed in 16/258 patients, CD33 was observed in 15/249 patients. Among the 20 positive patients tested for both markers, 6 expressed simultaneously CD13 and CD33. No significant relationship with the differentiation stage was detected and no effect on survival could be observed by statistical analysis. A number (91.4%, From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on February 6, 2015. For personal use only. 1608 BOUCHEIX ET AL 100 LALA87 T-ALL subgroups .. ... 80 n 6. 8 I ' ..............x . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ...*:........ W CI T1A-ALL (N-6) TlB-ALL (N-20) T2-ALL (N-35) T3-ALL (N-39) O U.a. &!A. P....... X L *............ h: :A......... ...... . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . p. . . .0.53 ........ = 40 20 0 X B1-ALL (N-32) BZ-ALL (N-100) B3-ALL (N-105) Fig 4. DFScurvesaccording to the wbdauificationof B- and I 1 2 3 221/258) of B-ALL tested for the CD9 antigen4' expressed this marker, but without any prognostic impact. The level of differentiation was not related to the other main parameters such as age or WBC count. T-lymphoidlineage ALL. For the T-lymphoid lineage, an accurate differentiation stage assignment was possible for 81% of the 150 cases. T-cell ALL were almost equally distributed among the three levels of differentiation with T1 (30, 6%), T2 (26, 6%), and T3 (28, 7%). The evolution according to the level of differentiation (TlA, TlB,T2, T3) did not show significant differences between the subgroups. Comparisons on the basis of individual markers showed no significant differences in term of DFS according to the presence of either CD1 or CD3. However, the 3-year survival was significantly better for patients whose cells expressed the CD1 antigen (63% for CDI+ patients, 42% for CDl+ patients, P = .03). Among the 130 patients with T-ALL tested for CDIO, 38 of them (29%) expressed CD10, whereas 92 (71%) did not express CDIO. Best overall survival was for CD10+ T-ALL patients, but the trend was not significant ( P = .M). However, there was a favorable outcome for DFS of the T-ALL 4 5 Yeus T-ALL. The median DFS and 3year DFS are indicated in the table. patients with CD10 antigen on leukemic cells (Fig 5). The frequency of CD10 expression increased with the level of differentiation; as to the age, 26 of 99 (26%) below 35 years and 12 of 31 (39%) above 35 years were CD10'. In contrast, HLA class I1 (121131 tested, 9%) and CD9 antigen expression (20/101 tested, 19.8%) werenot correlated withthe prognosis. Myeloid antigen coexpression (CD13 and/or CD33) was examined in 117 patients; leukemic cells of12 patients (10.2%) were positive for at least one of the two markers, more frequently CD33 than CD13. Indeed, CD13 was observed in 4 of 107 patients, whereas CD33 was observed in IO of 95 patients. Among the 11 positive patients tested for the two markers, 2 of them expressed both. A significant relation with the differentiation stage was detected because 4 of 11 T1A were positive with 9 of 44 for the whole TI stage, whereas only 2 of 30 and 2 of 32 were positive for the T2 and T3 stages, respectively. Because the criteria of inclusion were morphologic and cytochemical, we can't exclude that some of the TIA patients had MO AML. Undifferentiated ALL. The number of patients with undifferentiated ALL (15 cases) was too small for evaluating From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on February 6, 2015. For personal use only. LALA87. 1609IMMUNOPHENOTYPE AND OUTCOME 'Q... *g b 1 LALA87 CD20 in T-ALL 4 i.. 8. ** 6. * - g . * -.; ...b . . . 4*,* 0 DFS 3years months % n.r. 64 18.5 40 CDlO POS. (N-31) CDlO ntg. (N-73) b.................. **. . b..... * *... 4 ............. p = 0.04 4.* W...................... Fig 5. DFScurves of CD10' versusCD10-T-ALL.(n.r., not reachdl i 2 a prognosis impact. On the whole, the outcome of these patients was similar to that of B-lineage-related ALL. Twelve patients were tested for myeloid markers and only one of them was positive (CD13); 10 of the 11 patients tested for HLA class I1 were positive. Prognostic Factors According to Immunophenotype Groups: Univariate and Multivariate Analysis Initial WBC count and age are the most commonly described prognostic factors in adult ALL. They were validated in the LALA87 trial.3' When looking at the influence of the phenotype on these parameters in a univariate analysis, it appears that the WBC count was the most important prognostic factor in the B-lineage ALL, whereas age was the most important criterion for T-ALL. The main outcomes according to age and WBC count for B- and T-ALL are detailed in Table 3. A multivariate analysis was performed in T-ALL with age, WBC count, platelets, and presence or absence of CDlO antigen. Only WBC count ( P = .05)was found for overall survival, whereas for DFS, age less than 35 (P = .004), 5 years 4 3 WBC count less than 30 X 109L (P < .OOl), and presence of CDlO ( P = .001) were three independent favorable prognostic factors. Similarly, in B-ALL, WBC count was the only prognostic factor found for overall survival (P = .02) whereas WBC count less than 30 X 109L (P< .001) and platelets greater than 100 X 10"L (P< .OO1) were found as the two independent favorable prognostic factors for DFS. DISCUSSION A considerable number of markers is presently available for the immunophenotyping of ALL. In the LALA87 trial, we tested a set of markers commonly used in 1987 to evaluate the prognostic impact of an immunologic classification on the outcome of patients included in this protocol and to search for an adapted therapeutic strategy. All patients were submitted to a similar induction protocol and postremission was randomly allocated according to age and availability of a HLA sibling donor. Furthermore, most of the included patients benefited from an accurate immunologic analysis allowing clinicobiologic correlations. The previously re- Table 3. Relevance of the Usual Prognosis Criteria of Adult ALL According to the B or T lmmunophenotype for All Patients Analyzed Median Survival No. B-ALL 36 1 WBC < 30 X 1 0 ~ ~ 251 WBC > 30 X 1091~ 110 Age 1 3 5 77 183 Age >35 70.8 178 T-ALL 150 WBC < 30 X 1091~ 84.665 WBC > 30 X 1 0 7 ~ 77.6 85 Age <35 (941 80.9 115 Age >35 34 Abbreviation: NR, not reached. % CR (no.) % 3-yr Survival (mod 76.4 (192) 31.9 19.5 68 (75) 16.7 11 15.2 (141) 21 (126) 14 28.6 (55) (66) 82.8 (29) 28 56.7NR 42.4 16.6 NR 13 8.5 2 3.4 8 t4 37.9 2 3.9 1426.4 2 3.7 2 6.3 t 5.5 54.9 t 4.7 t 8.2 PValue .0001 .03 .04 ,002 DFS (mod % 3-yr DFS (?SE) 15 36 2 3.8 2 4.5 32.8 t 4.3 2 4.4 15 NR 14 NR 55.2 41.4 54.1 27.2 2 7.0 2 6.4 t 5.4 2 9.4 PValue ,0002 .4 .03 ,004 From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on February 6, 2015. For personal use only. BOUCHEIX ET AL 1610 ported difference in the clinical presentation and the prognosis between T- and B-lineage leukemia^'.^' appears to be very significant in this trial. We confirmed the generally better outcome of T-ALL and our results are consistent with the fact that T-ALL and B-ALL are two distinct clinical entities. The favorable impact of T phenotype was found in this trial in a large multivariate analysis onboth overall survival and DFS. A further level of stratification introduced by the investigation of cytogenetic and molecular rearrangements would be important, at least for B-ALL, because patients with bcr-ab1 rearrangement have a poor prognosis. In the LALA87 trial, karyotype was performed in 274 patients and Ph chromosome was found in 58; because CR was obtained in only 57% of these patients and only one of them is still alive, these patients contribute to the poor prognosis of B-ALL in this trial. Interestingly, the outcomes with the available postremission therapy regimens strongly differ especially in the alloBMT arm where the difference between the B- and T-cell leukemias disappeared. No statistical difference was observed in the ABMT arm. However, the lack of statistical significance could be explained by the small sample size of each patient group. Indeed, there is no obvious reason for this difference of outcome according to the type of postremission therapy. Nevertheless, it has to be noticed that patients in the alloBMT arm did not receive cytosine arabinoside, which is considered to be a very effective drug in T-ALL4'. The immunophenotypic subclassification of B cell leukemias did not show significant differences according to the level of differentiation. The usual comparison of CD10+ versus CD10- non T-ALL (usually referred as null-ALL) is not very informative. It has to be noticed that the CD10non T-ALL, frequently grouped in the literature are a mixture of undifferentiated, B1, and B3B ALL in the classification usedin this trial. In our opinion, there isnot longer any biologic relevance to classifying ALL in this way. cytoplasmic p chains, not included in this study for technical reasons, are an additional potentially useful marker; they are usually associated with late differentiation stages of B-ALL, but they do not fit strictly within a given stage of the classification proposed in this study.' The incidence of myeloid antigen coexpression as judged by the presence of the CD13 or CD33 antigens was limited to less than 10%of the patients and no clinical correlation could be observed. The frequency and clinical importance of myeloid markers has often been reported in the litterat~re""~; however, no satisfactory interpretation can be drawn from these studies because results are contradictory. In the large series of 633 children from Ludwig et al," the 43 B-ALL patients with myeloid markers had a high remission rate and the LFS was identical to the corresponding myeloid marker-negative patients; also, Bradstock et all3did not observe adverse effects of myeloid markers in a mixed population of adult and children with B-ALL. On the other hand, Sobol et all' observed myeloid antigen coexpression in 17 of 55 adult B-ALL and they reported a lower rate of CR and a shorter survival. Large numbers of uniformly treated patients are needed to assess the prognosis of these markers within a given protocol. Subclassification of T-ALL showed no significant differ- ences. However, the T1A group (1 1 patients with isolated CD7 positivity), seemed to have a slightly worse prognosis in terms of survival. An interesting point in the group of TALL is the impact of the CDlO expression; the CDlO+-ALL (30% of T-ALL) had a better prognosis than the CD10-, even when using a multivariate analysis. A similar conclusionwas drawn from a large study in childhood ALL.42 In this trial, CDlO expression seems to be an independent prognostic factor that needs to be confirmed byother studies. On the other hand, no effect on prognosis of the HLA class I1 (8% of the T-ALL) marker was observed. Regarding the 13 cases of myeloid antigen coexpression (9%) in T-ALL, most of them were found in early differentiation stages. The biologic significance of these leukemias and related normal cells has been addressed in several paper^^'.^^; in some cases, it has been shown that the leukemic cells gave rise to both T-cell and myeloid colonies in ~ i t r o . ~ ' In conclusion, this study, within the limits of the treatment regimens, supports some previous observations on the link between immunologic phenotype and prognosis for the major T- and B-cell-lineage-related adult ALL. The design of the trial outlines some particular findings such as the loss of prognostic significance of the immunophenotype for patients receiving alloBMT in first remission and the different values of classical prognostic parameters between T- and B-cell leukemia. These statements need to be confirmed by other studies to be incorporated in the design of future therapeutic trials. ACKNOWLEDGMENT Participating centers were HBpital Saint Louis, Paris, France (Drs C. Gisselbrecht, J.M. Miclea, S . Castaigne), HBpital Edouard Herriot, Lyon, France (Drs D. Fibre, C. Sebban, J. Troncy), Centre HospiJ. Reiffers,B.David), talier,Bordeaux,France(DrsA.Broustet, Centre Hospitalier, Toulouse, France (Drs J. Pris, M. Attal, F. Huguet), Centre Hospitalier, Nancy, France (Dr F. Witz), HBpital Henri Mondor,CrCteil,France (Drs J.P. Vernant, Cordonnier, Rochant), Centre Hospitalier, Besangon, France (Drs J.Y. Cahn, M. Flesh, P. HervC), HBpital PitiC SalpCtribre, Paris, France (Drs V. Leblond, L. Sutton), HBpital Cochin, Paris, France (Drs F. Dreyfus, B. Varet), Centre Hospitalier, Nice, France (Dr N. Gratecos), Centre associCs deBelgique(DrsJ.L.Michaux,A.Delannoy,A.Bosly),Centre Hospitalier, Grenoble, France(Dr M. Michallet), Centre Hospitalier, Lille,France (Dr J.P. Jouet), InstitutGustaveRoussy,Villejuif, France (Drs M. Hayat, J.L. Pico), Centre Hospitalier, Dijon, France (Drs D. Caillot, H. Guy), HBpital Saint Antoine, Paris, France (Dr A.Najman),CentreAnticancCreuxdeMarseille,France(DrsD. Maraninchi, J.A. Gastaut), Centre Hospitalier, Caen, France (Dm X. Troussard, M. Leporrier), Centre Hospitalier, Reims, France(Dr B. Pignon), Centre Hospitalier, Strasbourg, France (Dr Dufour), Centre Hospitalier, Saint Etienne, France (Drs J. Jaubert, D. Guyotat), Centre Hospitalier, Lyon Sud, France (Dr D. Espinousse), HBpital Val de Grice, Paris,France (Drs G. Nedellec, R.Martoia, G. Auzanneau), Centre Hospitalier, Colmar, France (Drs B. Audhuy, R. Mors), CentreHospitalier,Limoges,France(Dr D. Bordessoule),Centre Hospitalier, Brest, France (Dr J. Bribre), Centre Hospitalier, Avignon, France (Dr G. Lepeu), Centre Hospitalier,Annecy, France (Dr C. Martin), Centre Hospitalier, Clermont Ferrant, France(Dr P. Travade),HBpitalAntoine BCclbre, Clamart, France (Dr G. Tertian), Centre AnticancCreux de Rennes, France (Dr C. Gandhour), Centre Hospitalier, Sud, Rennes, France (Dr R. Leblay), HBpital St Anne Toulon,France (Dr D. Jaubert). HBpitalBeaujon, Clichy, France From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on February 6, 2015. For personal use only. "87, IMMUNOPHENOTYPE AND OUTCOME (Dr J.L. Bernard), Centre Hospitalier, St Pierre de la RCunion, France (Dr C. Gamier), Centre Antoine Lacassagne, Nice, France (Dr A. Thyss), Centre Hospitalier Leclerc, Dijon, France (Dr J.M. Nahboltz), Centre Hospitalier, Meaux, France (Dr C. Allard), Centre Hospitalier, Poitiers, France (Dr F. Guilhot), Centre Hospitalier, Colombes, France (Dr F. Teillet), HBpital RenC Huguenin, Saint Cloud, France (Dr M. Janvier). REFERENCES 1. Brouet JC, Seligman M: The immunological classification of acute lymphoblastic leukemias. Cancer 42:817, 1978 2. Reinhen EL, Kung PC, Goldstein G , Levey RH, Schlossman S F Discrete stages of human intrathymic differentiation: Analysis of normal thymocytes and leukemic lymphoblasts of T cell lineage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 77:1588, 1980 3. Nadler LM, Korsmeyer SJ, Anderson KC, Boyd AW, Slaughenhoupt B, Park E, Jensen J, Coral F, Mayer RJ, Sallan SE, Ritz J, Schlossman S F B-cell origin of non T-cell acute lymblastic leukemia : A model for discrete stages of neoplastic and normal pre-B cell differentiation. J Clin Invest 74:322, 1984 4. Foon KA, Todd RF: Immunologic classification of leukemia and lymphoma. Blood 68: 131, 1986 5. Freedman AS, Nadler LM: Cell surface markers in hematologic malignancies. Semin Oncol 14:193, 1987 6. Loken MR, Shah VO, Dattlio KL, Civin CI: Flow cytometric analysis of human bone marrow: II. Normal B lymphocyte development. Blood 70:1316, 1987 7. Garand R, Bene MC, andthe GEIL: Incidence, clinical and laboratory features, and prognostic significance of immunophenotypic subgroups in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: The GEIL experience, in Ludwig WD, Thiel E (eds): Recent Advances in Cell Biology of Acute Leukemia. Impact on Clinical Diagnosis and Therapy. Recent Results in Cancer Research, v01 131. Berlin, Germany, Springer-Verlag, 1993, p 283 8. Traweek ST: Immunophenotypic analysis of acute leukemia. Am J Clin Pathol 99:504, 1993 9. Greaves MF, Brown C, Rapson NT, Lister A: Antisera to acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 4:67, 1975 10. LeBien TW, McCormack RT: The common acute lymphoblastic leukemia antigen (CD10)-emancipation from a functional enigma. Blood 73:625, 1989 1l . Soboi RE, Mick R, Royston I, Davey FR, Ellison RR, Newman R, Cuttner J, Griffin JD, Collins H, Nelson DA, Bloomfield CD: Clinical importance of myeloid antigen expression in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med 316: 1111, 1987 12. Crist W, Pullen J, Boyett J, Falleta J, van Eys J, Borowitz, Jackson J, Dowel1 B,Russell C, Quddus F, Ragab A, Vietti T: Acute lymphoid leukemia in adolescents: Clinical and biologic features predict a poor prognosis. A Pediatric Oncology Group study. J Clin Oncol 6:34, 1988 13. Bradstock KF, Kirk J, Grimsley PG, Kabral A, Hughes WG: Unusual immunophenotypes in acute leukaemias: incidence and clinical correlations. Br J Haematol 72512, 1989 14. Childs CC, Hirsch-Ginsberg C, Walters RS, Anderson BS, Reuben J, Trujillo JM, Cork A, Stass SA, Freireich ET, Zipf TF: Myeloid surface antigen-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia (My+ ALL): Immunophenotypic, ultrastructural, cytogenetic and molecular characteristics. Leukemia I1:777, 1989 15. Ludwig WD, Bartram CR, Harbott J, Koller U, Haas OA, Hansen-Hagge T, Heil G, Seibt-Jung H, Teichmann JV, Ritter J, Knapp W, Gadner H, Thiel E, Riehm H: Phenotypic and genotypic heterogeneity in infant acute leukemia I. acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 6:431, 1989 16. Guyotat D, Campos L, Shi ZH, Charrin C, Treille D, Magaud 1611 JP, Fiere D: Myeloid surface antigen expression in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 9:664, 1990 17. Pui CH, Behm FG, Singh B, Rivera GK, Schell MJ, Roberts WM, Crist WM, Mirro J Jr: Myeloid-associated antigen expression lacks prognostic value in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia treated with intensive multiagent chemotherapy. Blood 75: 198, 1990 18. Wiersma SR. Ortega J, Sobel E, Weinberg KI: Clinical importance of myeloid-antigen expression in acute lymphoblastic leukemia of childhood. N Engl J Med 324:800, 1991 19. Pui CH, Behm FG, Crist WM: Clinical and biologic relevance of immunologic marker studies in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 82:343, 1993 20. Hoelzer D, Thiel E, Loffler H, Buchner T, Ganser A, Heil G , Koch P, Freund M, Diedrich H, Ruhl H, Maschmeyer G, Lipp T, Nowrousian MR, Burkert M, Gerecke D, Ralle H,Miiller U, Lunscken C, Fiille H, Ho AD, Kiichler R, Busch F W , Schneider W, Gorg C, Emmerich B, Braumann D, Vaupel HA, von Paleske A, Bartels H, Neiss A, Messerer D: Prognostic factors in a multicenter study for treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adults. Blood 71:123, 1988 21. Hoelzer D: High-dose chemotherapy in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Semin Hematol 28:84, 1991 22. Berman E, Weiss M, Kempin S, Gee T, Bertino J, Clarkson B: Intensive therapy for adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Semin Hematol 28:72, 1991 23. Linker CA, Levitt LJ, O'Donnell M, Forman SJ, Ries CA: Treatment of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia with intensive cyclical chemotherapy: A follow-up report. Blood 11:2814, 1991 24. Blume KG, Forman SJ, Snyder DS, Nademanee AP, O'Donne1 MR, Fahey JL, Krance RA, Sniecinski LT, Stock AD, Findley DO, Lipsett JA, Schmidt GM, Nathwani MB, Hill LR, Metter GE: Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for acute lymphoblastic leukemia during first complete remission. Transplantation 43:389, 1987 25. Weisdorf DJ, McGlave PB, Ramsay NK, Miller WJ, Nesbit ME, Woods WG, Goldman AL,Kim TH, Kersey JH: Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for acute leukemia: Comparative outcomes for adults and children. Br J Haematol 69:351, 1988 26. Vemant JP, Marit G, Maraninchi D, Guyotat D, Kuentz M, Cordonnier C, Reiffers J: Allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first complete remission. J Clin Oncol 6:227, 1988 27. Horowitz MM, Messerer D, Hoelzer D, Gale RP, Neiss A, Atkinson K, Barrett AJ, Biichner T, Freund M, Heil G , Hiddemann W, Kolb HJ, L6ffler H, Marmont AM, Maschmeyer G , Rimm A A , Rozman C, Sobocinski KA, Speek B, Thiel E, Weisdorf DJ, Zwaan FE, Bortin MM: Chemotherapy compared with bone marrow transplantation for adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia in first remission. Ann Int Med 115:13, 1991 28. Gorin NC, Herve P, Aegerter P, Goldstone A, Linch D, Maraninchi D, Bumett A, Helbig W, Meloni G , Verdonck LF, De Witte T, Rizzoli V, Carella A, Parlier Y, Auvert B, Goldman J: Autologous bone marrow transplantation for acute leukemia in remission. Br J Haematol 64:385, 1986 29. Kersey JH, Weisdorf D, Nesbit ME, LeBien TW, Woods WG, McGlave PB, Kim T, Vallera DA, Goldman AI, Bostrom B, Hurd D, Ramsay NKC: Comparison of autologous and allogeneic bone marrow transplantation for treatment of high-risk refractory acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Eng J Med 317:461, 1987 30.Kersey JH: The role ofmarrow transplantation in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 7: 1589, 1989 31. Fiere D, Lepage E, Sebban C, Boucheix C, Gisselbrecht C, Vemant JP, Varet B, Broustet A, Cahn JY, Rigal-Huguet F, Witz F, Michaux JL, Michallet M, Reiffers J: Adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: A multicentric randomized trial testing Bone Marrow From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on February 6, 2015. For personal use only. 1612 Transplantation as postremission therapy (LALA87 protocol). J Clin Oncol 10:1190 1993 32. Bennett JM, Catovsky D, Daniel MT, Flandrin G, Galton DAG, Gralnick HR, Sultan C: Proposals for the classification of the acute leukaemias. Br J Haematol 33:451, 1976 33. Gaynor J, Chapman D, Little C, McKenzie S , Miller W, Andreeff M, Arlin Z, Berman E, Kernpin S, Gee T, Clarkson B: A cause-specific hazard rate analysis of prognostic factors among 199 adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 6:1014, 1988 34. Bernard A, Boumsell L, Dausset J, Milstein C, Schlossman SF: Leukocyte Typing. Berlin, Germany, Springer-Verlag, 1984 35. Reinherz EL, Haynes BF, Nadler LM, Berstein ID: Leukocyte Typing 11. Berlin, Germany, Springer-Verlag, 1986 36. McMichael AJ: Leukocyte Typing 111:White Cell Differentiation Antigens. Oxford, UK, Oxford University, 1987 37. Kaplan EL, Meier P: Non parametric estimation from incomplete observations. J Am Stat Assoc 53:457, 1958 38. Pet0 R, Pike ML, Armitage P: Design andanalysis of randomized clinicals requiring prolonged observation of each patient. Br J Cancer 35: I , 1997 39. Cox DR: Regression models and life tables. J R Stat SOCB 34: 187, 1972 40. Kersey JH, Lebien T, Abramson CS, Newman R, Sutherland R, Greaves MF: p24, a human leukemia associated and lymphohem- BOUCHEIX ET AL opoietic progenitor cell surface structure identified with monoclonal antibody Ba2. J Exp Med 153:726, 1981 41. Hoelzer D: Prognostic factors in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 6:49, 1992 42. Pui CH, Rivera GK, Hancock ML, Raimondi SC, Sandlund JT, Mahmoud HH, Ribeiro RC,Furman WL, Hunvitz CA, Crist WM. Behm FG: Clinical significance of CD10 expression in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 7:35, 1993 43. Haynes BF, Denning SM, Singer KH, Kurtzberg J: Ontogeny of T-cells precursors: A model for the initial stages of human T-cell development. Immunol Today 3:87, 1989 44. Kurtzberg J, Waldmann AW, Davey MP, Bigner SH, Moore JO, Hershfield MS, Haynes BF: CD7'. CD4-, CD8- acute leukemia: A syndrome of malignant pluripotent lymphohematopoietic cells. Blood 2:381, 1989 45. Thiel E, Kranz BR, Raghavachar A, Bartram CR. Loffler H, Messerer D, Ganser A, Ludwig WD, Buchner T, Hoelzer D: Prethymic phenotype and genotype of pre-T (CD7'/ER-)-cell leukemia and its clinical significance within adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 5:1247, 1989 46. Garand R, Voisin S, Papin S, Praloran V, Lenormand B, Favre M, Philip P, Bemier M, Vanhaecke D, Falkenrodt A, Bene MC, Faure G andthe GEIL: Characteristics of Prom-ALL subgroups: Comparison with late T-ALL. Leukemia 7: 161, 1993 From www.bloodjournal.org by guest on February 6, 2015. For personal use only. 1994 84: 1603-1612 Immunophenotype of adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia, clinical parameters, and outcome: an analysis of a prospective trial including 562 tested patients (LALA87). French Group on Therapy for Adult Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia C Boucheix, B David, C Sebban, E Racadot, MC Bene, A Bernard, L Campos, H Jouault, F Sigaux and E Lepage Updated information and services can be found at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/84/5/1603.full.html Articles on similar topics can be found in the following Blood collections Information about reproducing this article in parts or in its entirety may be found online at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/site/misc/rights.xhtml#repub_requests Information about ordering reprints may be found online at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/site/misc/rights.xhtml#reprints Information about subscriptions and ASH membership may be found online at: http://www.bloodjournal.org/site/subscriptions/index.xhtml Blood (print ISSN 0006-4971, online ISSN 1528-0020), is published weekly by the American Society of Hematology, 2021 L St, NW, Suite 900, Washington DC 20036. Copyright 2011 by The American Society of Hematology; all rights reserved.

© Copyright 2026