PDF (397 kB)

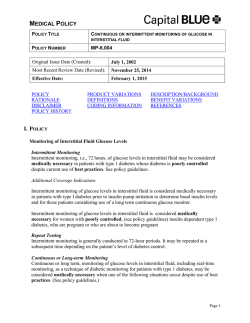

Perspectives The Lancet Technology: January, 2015 Science Photo Library Eric Topol Test results from your smartphone: flipping the consultation room? For more on Elle Dormer’s experience with diabetes or to attend a London seminar at the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation on managing diabetes with CGM see https:// www.jdrf.org.uk/ or email [email protected] For more on Jessica Castle see http://www.ohsu.edu/xd/health/ services/providers/index. cfm?personid=2011 Photo Elle Dormer For more on Eric Topol see http:// www.stsiweb.org/translational_ research/research_faculty/topol/ and @EricTopol 408 “It was life-changing from the outset”, says Elle Dormer about the continuous glucose monitor (CGM) her 4-year-old son, who has type 1 diabetes, has had for the past year. “For the first time, we could make treatment decisions in close to real time without the need for endless finger stick tests.” The CGM monitors his glucose concentrations and relays this to an external handheld receiver, whilst a further adaptation enables these results to be sent to Elle’s smartphone. Elle’s son’s glycated haemoglobin A1c is exemplary for a child with type 1 diabetes, but the monitor has also given them both freedom and reassurance for normal day-to-day activities. “Previously I was setting an alarm to get up two or three times a night and check on his blood glucose because he had night-time hypoglycaemic attacks”, explains Elle. “Now the receiver alarms to signal rapid blood sugar changes and hypos. Even when he is at preschool or on a play date I can keep an eye on his blood sugar.” Jessica Castle, Assistant Professor of Medicine (endocrinology, diabetes, and clinical nutrition) at the Oregon Health and Science University School of Medicine in the USA, researches CGM and uses CGM in the care of her patients. “There is evidence to support the use of CGM for improving glucose control and reducing hypoglycaemia”, she says. But Castle also acknowledges that “CGM can be lifesaving, but the choice of using the technology is a personal one. It adds cost and takes up additional ‘real estate’ on the body”. CGM is just one example of the many wearable health devices already in clinical use. Other such devices that have been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration include real-time ECG monitors, blood pressure monitors, and even an otoscope. As digital medicine advocate Eric Topol, Director of the US Scripps Translational Science Institute, points out, ”another hundred plus sensors will be launched this year”. Topol is a practising cardiologist and also sits on the board of directors or advisory board for a host of medical technology companies. “We are digitising human beings, but it’s also a democratisation. Wearable technology coupled with the computing power of smartphones places in the hands of patients the ability to carry out laboratory tests, and to monitor and diagnose themselves without being dependent on physician visits for tests. This technology means that information is transparent, the consumer or the patient is not just engaged but knows everything about themselves, and rightfully so”, he says. Topol’s view certainly fits with Elle’s experience. “It’s very empowering”, she says, “at hospital appointments now I tell the doctor what has been happening”. Elle, who lives in London, says she still gets important advice from her son’s medical team, but since CGM is fairly new to clinical practice in the UK a lot of her information on the technology that is available and how to use it comes from dedicated social media forums. Not all medical professionals are convinced by CGM and other wearable devices, expressing concerns that they represent “high-cost, high-attention” health monitoring which, far from being democratic, is available only to a minority of wealthy, well-educated patients. In the UK, a complicated application process to obtain funding for these devices, and problems with accessing devices currently marketed only in the USA, mean these concerns are a reality for many patients. There are also questions around data processing, privacy, and security. Topol acknowledges that “just collecting a huge dataset is not enough, results obtained by patients need to be processed and presented in a consumer friendly way, and one that can easily be shared with the supervising physician without affecting their time and attention”. It seems clear from both consumer level pricing and marketing that many wearable medical devices are being marketed directly to patients themselves. Whether this technology can really empower patients or just represents another market for medical device manufacturers remains to be seen. What is undeniable, however, is that the growth of such technology calls for an evolution of the physician’s role in advocating for and educating patients. In a fast-moving field it’s more important than ever for physicians to stay up to date with what device manufacturers are offering—not only to advise patients on what works, how to access it, and how to get the best out of it, but also to evaluate the effectiveness and cost efficiency of these devices, to push device companies to deliver the best possible product, and to ensure government regulation protects patients as consumers. Naomi Lee [email protected] www.thelancet.com Vol 385 January 31, 2015

© Copyright 2026