Management of hand-foot syndrome in patients treated

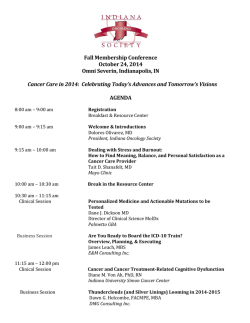

ARTICLE IN PRESS European Journal of Oncology Nursing (2004) 8, S31–S40 www.elsevier.com/locate/ejon Management of hand-foot syndrome in patients treated with capecitabine (Xelodas) Yvonne Lassere, Paulo Hoff Clinical Protocol Administration, MD Anderson Cancer Center, 1515 Holcombe Unit 426, Houston TX 77030, USA KEYWORDS: Capecitabine; Xelodas; Hand-foot syndrome Summary Comparative trials of capecitabine (Xelodas) versus 5-FU/LV in metastatic colorectal cancer have shown that hand-foot syndrome (HFS) was the only clinical adverse event occurring more frequently with capecitabine. Most patients with HFS present with dysesthesia, usually with a tingling sensation in the palms and soles of the hands and feet. This can progress in 3–4 days to burning pain plus well-defined symmetric swelling and erythema. The hands tend to be more commonly affected than the feet, and might even be the only area affected in some patients. HFS can interfere with the general activities of daily living, especially when blistering, moist desquamation, severe pain or ulceration occurs. While HFS is manageable, if ignored it can progress rapidly. However, dose interruption and reduction of capecitabine usually leads to a rapid reversal of signs and symptoms without long-term consequences. Nurses play a key role in educating patients how to recognise HFS, when to interrupt treatment and how to adjust the dose to maintain effective therapy with capecitabine over the long term. It is particularly important that patients and nurses are aware that dose interruption/reduction does not affect the overall antitumour efficacy of capecitabine. r 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Zusammenfassung Vergleichende Versuche mit Capecitabine (Xelodas) im Vergleich zu 5-FU/LV bei metastasierendem kolorektalem Karzinom haben gezeigt, dassdas Hand-FuX-Syndrom (HFS) die einzige Nebenwirkung ist, die mit Capecitabine ha ¨ufiger auftritt. Bei den meisten Patienten mit HFS tritt Dysa ¨sthesie auf, normalerweise mit einem Prickeln auf den Handfla ¨chen und FuXsohlen. Dies kann innerhalb von 3 bis 4 Tagen zu einem brennenden Schmerz und klar definierten symmetrischen Schwellungen und Erythem fortschreiten. Die Ha ¨nde sind im allgemeinen o ¨fter befallen als die Fu ¨Xe und ko ¨nnen bei einigen Patienten sogar die einzigen befallenen Bereiche sein. HFS kann die normalen Verrichtungen des ta ¨chtigen, besonders, wenn Blasenbildung, feuchte ˇglichen Lebens beeintra Corresponding author. Tel.: +1-713-792-6512; fax: +1-713-745-2845. E-mail address: [email protected] (Y. Lassere). 1462-3889/$ - see front matter r 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2004.06.007 ARTICLE IN PRESS S32 Y. Lassere, P. Hoff Abschuppung, starke Schmerzen oder Geschwu ¨rbildung auftreten. Obwohl man HFS behandeln kann, entwickelt es sich rapide, wenn man es ignoriert. Zeitweiliges Absetzen oder eine Verminderung der Dosierung von Capecitabine fu ¨hrt jedoch normalerweise zu einem raschen Abklingen der Anzeichen und Symptome ohne langfristige Folgen. Das Pflegepersonal spielt eine fu ¨hrende Rolle dabei, die Patienten darin zu unterweisen wie man HFS erkennt, wann man die Benandlung unterbrechen sollte und wie man die Dosierung vera ¨ndert, um eine wirksame Behandlung mit Capecitabine langfristig aufrecht zu erhalten. Besonders wichtig ist dabei, dass Patienten und Pflegepersonal wissen, dass die Unterbrechung oder Minderung der Dosierung die langfristige turnorbeka ¨mpfende Wirksamkeit von Capecitabine nicht beeintra ˇchtigt. r 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Introduction Hand-foot syndrome Capecitabine (Xelodas) was specifically designed for oral administration, to deliver 5-FU to the tumour site and to avoid systemic 5-FU exposure (Ishikawa et al., 1998; Miwa et al., 1998). As discussed in article 1 in this Supplement (Sternberg et al., 2004), the unique tumour-selective conversion of capecitabine to active 5-FU is achieved by a 3-step enzymatic process. The final step of the conversion is mediated by the enzyme thymidine phosphorylase, which is found at higher levels in cancer cells compared with normal tissues. As a result, more of the active anticancer agent 5-FU is produced where it is needed (i.e. within cancer cells rather than in healthy tissues). Oral capecitabine is being increasingly accepted into clinical practice as it permits convenient administration in a home-based setting. Capecitabine tablets are taken orally twice daily approximately 12 h apart (after breakfast and after dinner) for 2 weeks followed by a 1-week, treatment-free period. After this 1-week ‘rest’ period, the patient starts the next cycle. The normal recommended dosage is 1250 mg/m2 twice daily, unless dose reduction is indicated because of adverse events. At this dosage, capecitabine is generally well tolerated, with a low incidence of grade 3/4 adverse events (see article 2 in this supplement). One of the most common adverse events associated with its use in clinical trials and in clinical practice is hand-foot syndrome (HFS), which is rarely serious and never life-threatening (Cassidy et al., 2002). However, HFS can significantly interfere with the activities of normal daily living. The aim of the current paper is to describe the occurrence of HFS in capecitabine-treated patients, its nature, recognition, and severity, and the role of the oncology nurse in managing HFS optimally. HFS, which is also known as palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia (or PPE), was first described in the literature in 1974 in patients receiving mitotane therapy for hypernephroma (Burgdorf et al., 1982; Baack and Burgdorf, 1991; Nagore et al., 2000). In the early 1980s, it was referred to as chemotherapy-induced acral erythema, and appeared to be associated with continuous exposure to various chemotherapy drugs (Baack and Burgdorf, 1991). Description/classification In early reports, acral erythema was characterised by erythema, numbness, tingling, dysesthesia, and/or paraesthesia on the palms or soles; the condition can also rarely affect the trunk, neck, chest, scalp, and extremities (Baack and Burgdorf, 1991). In advanced cases, patients experience pain with swelling of the skin, and even desquamation, ulceration or blistering. HFS has been defined more recently as a distinct and specific presentation (Nagore et al., 2000). Most patients present with dysesthesia, usually with a tingling sensation of the palms and soles, which can progress in 3–4 days to burning pain plus well-defined symmetric swelling and erythema (Fig. 1a). The hands tend to be more commonly affected than the feet, and might even be the only area affected in some patients. Erythema is uncommon outside these areas, although occasionally a mild erythema or morbiliform eruption on the trunk, neck, chest and extremities can accompany the acral response (Baack and Burgdorf, 1991; Kroll et al., 1989). Blistering and desquamation (shedding of scales or small sheets of skin) may also ARTICLE IN PRESS Management of hand-foot syndrome S33 a protocol-specific, 3-grade system has generally been applied (Blum et al., 1999), which is a practical guide in clinical practice for dose reduction/interruption of capecitabine (Table 1). Mechanism of HFS Figure 1 Appearance of HFS. (a) Characteristic erythema associated with moderate HFS. (b) Without appropriate management, HFS can progress to an extremely painful and debilitating condition develop, particularly when the causative agent is not promptly discontinued. Dose reduction or discontinuation of the causative agent usually leads to a rapid reversal of signs and symptoms without long-term consequences. Nevertheless, HFS can interfere with the general activities of daily living, especially when blistering, moist desquamation, severe pain or ulceration occurs (Jucgla and Sais, 1997). Without prompt management, HFS can progress to an extremely painful and debilitating condition (Fig. 1b). Although HFS is not life threatening, as a cutaneous condition affecting the hands and feet, it can cause significant discomfort and impairment of function, potentially leading to worsened quality of life in patients receiving cytotoxic chemotherapy. Different systems have been used for the classification of HFS. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) has a general 3-grade classification system (Table 1). There are no grade 4 events in this HFS classification. There is also a World Health Organisation (WHO) classification system based on 4 grades (Table 1). In clinical trials of capecitabine 5-FU was the first agent to be consistently identified as a causative agent for HFS (Lokich and Moore, 1984) and, until the 1990s, was the agent most frequently associated with HFS, particularly when administered by continuous infusion (Bellmunt et al., 1988; Fabian et al., 1990; Leo et al., 1994; Ng et al., 1994). More recently, HFS has become recognised as one of the most common adverse events with capecitabine. The mechanism of HFS is unclear. In patients receiving 5-FU, HFS is dose-dependent and probably related to drug accumulation in the skin (Bellmunt et al., 1988; Leo et al., 1994), possibly of 5-FU metabolites (Diasio, 1998). Interestingly, HFS induced by 5-FU appears to be more common in elderly female patients (Meta-Analysis Group in Cancer, 1998), although no such age or gender association has been observed with capecitabine (Abushullaih et al., 2002; Cassidy et al., 2002). Neither the frequency nor severity of HFS appears to correlate with plasma concentrations of various capecitabine metabolites (Cassidy et al., 2002; Gieschke et al., 2002, 2003). One theory relating to capecitabine-associated HFS is that specialised skin cells (keratinocytes) might have upgraded levels of the enzyme thymidine phosphorylase (Asgari et al., 1999), which could be a cause of capecitabine metabolite accumulation, and hence result in an increased likelihood of developing HFS. Another theory is that capecitabine may be eliminated by the eccrine system (sweat secretion), resulting in HFS caused by an unknown mechanism relating to the increased number of eccrine glands on the hands and feet (Mrozek-Orlowski et al., 1999). HFS may also result from increased vascularisation and increased pressure and temperature in the hands and feet. In addition, long-term alcohol intake and strenuous physical activity may increase the likelihood of developing HFS. When examined under the microscope, tissues affected by HFS show general inflammatory changes, dilated blood vessels, oedema and white blood cell infiltration, although nothing really stands out as a clear marker for the condition (Abushullaih et al., 2002; Nagore et al., 2000). Consequently, there is no ideal diagnosis for HFS. In addition, HFS appears to differ according to the ARTICLE IN PRESS S34 Y. Lassere, P. Hoff Table 1 HFS grading according to National Cancer Institute (NCI) (Nagore et al., 2000), World Health Organisation (WHO) criteria (Nagore et al., 2000), and as used in capecitabine clinical trials (Blum et al., 1999). NCI grade NCI definition 1 2 3 Skin changes or dermatitis without pain, e.g. erythema, peeling Skin changes with pain, not interfering with function Skin changes with pain interfering with function WHO grade WHO definition Clinical lesion Histological findings 1 Dysesthesia/paraesthesia, tingling in the hands and feet Discomfort in holding objects and upon walking, painless swelling or erythema Painful erythema and swelling of palms and soles, periungual erythema and swelling Desquamation, ulceration, blistering, severe pain Erythema Dilated blood vessels of the superficial dermal plexus 2 3 4 1+oedema 2+fissuration Isolated necrotic keratinocytes in higher layer of the epidermis 3+blister Complete epidermal necrosis Clinical trial grade* Clinical domain Functional domain 1 Numbness, dysesthesia/paraesthesia, tingling, painless swelling or erythema Painful erythema, with swelling Moist desquamation, ulceration, blistering, severe pain Discomfort that does not disrupt normal activities 2 3 * Discomfort that affects activities of daily living Severe discomfort, unable to work or perform activities of daily living Note: Grade to correspond to high intensity on either clinical or functional domain. type of cytotoxic agent used. High rates of severe HFS have been reported with pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (D’Agostino et al., 2003), and the condition appears to be more common and severe (including infection and septicaemia) than in patients receiving capecitabine. Frequency of HFS with capecitabine HFS (all grades) occurred in approximately 50% of patients in early phase II studies of capecitabine single-agent therapy in metastatic breast cancer (MBC) (Blum et al., 1999) and metastatic colorectal cancer (MCRC) (Abushullaih et al., 2002; Van Cutsem et al., 2000), with 10% of patients experiencing severe (grade 3) HFS. A higher rate of severe HFS (52%, 12/23 cases) was reported in a Korean study of capecitabine in combination with docetaxel (Park et al., 2003), although this may be related to the ability of docetaxel to cause both HFS and nail toxicity. Because HFS is subjectively reported, standardisation is a challenge and cross-study comparison is difficult. A reliable appraisal of the frequency and severity of HFS has been obtained in phase III trials of capecitabine because of the larger numbers of patients enrolled. Colorectal cancer As discussed in the previous two articles in this Supplement, capecitabine has demonstrated a superior safety profile compared with 5-FU/LV in phase III trials of patients with MCRC (Cassidy et al., 2002); HFS was the only side effect occurring significantly more frequently on capecitabine (54% vs. 6%) with grade 3 HFS affecting only 17% of capecitabine-treated patients (Table 2). In addition, the lower dose of capecitabine used in combinations with oxaliplatin (XELOX/CAPOX) or irinotecan (XELIRI/CAPIRI) appears to result in a reduced rate of HFS compared with single-agent therapy (Cassidy et al., 2004a; Patt et al., 2004). Breast cancer In a large phase III trial comparing capecitabine in combination with i.v. docetaxel vs. i.v. docetaxel alone, the capecitabine/docetaxel combination ARTICLE IN PRESS Management of hand-foot syndrome S35 Table 2 Frequency of HFS (all grades and grade 3) with oral capecitabine vs. i.v. comparators in large phase II/ phase III trials. Capecitabine HFS (%) Comparator All grade Grade 3 All grade Grade 3 Colorectal cancer Capecitabine single-agent vs. 5-FU/LV (Cassidy et al., 2002) XELOX (Cassidy et al., 2004a) vs. FOLFOX-4 (de Gramont et al., 2000) XELIRI (Patt et al., 2004) vs. FOLFIRI (Douillard et al., 2000) CAPOX vs. FUFOX (Arkenau et al., 2004) Breast cancer Capecitabine+docetaxel vs. docetaxel (O’Shaughnessy et al., 2002) 54 36 41 30 17 3 6 1 6 29 17 27 1 0 0 0 64 24 8 1 CAPOX=oxaliplatin on days 1&8+capecitabine on days 1–14, every 3 weeks; FOLFIRI=irinotecan on day 1+bolus 5-FU/LV, followed by 5-FU (22-hour infusions) on days 1&2, every 2 weeks; FOLFOX=oxaliplatin on day 1+bolus 5-FU/LV, followed by 5-FU (22-hour infusions) on days 1&2, every 2 weeks; FUFOX=oxaliplatin+bolus 5-FU/LV on days 1, 8, 15 and 22, every 5 weeks; XELIRI=irinotecan on day 1+capecitabine on days 1–14, every 3 weeks; XELOX=oxaliplatin on day 1+capecitabine on days 1–14, every 3 weeks. was generally as well tolerated as docetaxel singleagent therapy, with HFS being the only notable exception (O’Shaughnessy et al., 2002). The overall rate of HFS was 64% in patients receiving capecitabine/docetaxel, with 24% of patients experiencing grade 3 HFS (Table 2). These rates of HFS are similar to those previously noted during capecitabine single-agent therapy in patients with other solid tumour types. Therefore, although the overall tolerability of oral capecitabine was good, the majority of patients developed HFS, which was severe in 17–24% of patients. It is important that the syndrome is well managed to prevent progression to a more severe grade of HFS, to avoid capecitabine dose reductions and to limit the need for discontinuation of capecitabine therapy. Management of HFS Dose interruption followed, if necessary, by dose reduction should be the mainstay of HFS management. Reducing the capecitabine dose without interruption at the first signs of HFS is likely to result in progression of the syndrome. To deliver capecitabine therapy as effectively as possible requires that patients become active, educated participants in their own treatment, and that side effects be prevented, recognised and managed adeptly (Gerbrecht, 2003). An example of managing a patient with MCRC who develops HFS while receiving capecitabine is shown in Fig. 2. Patients should, therefore, be made aware of the first signs and symptoms of HFS and instructed, upon development of grade 2 or 3 symptoms, to interrupt treatment until improved to grade 0 or 1. Treatment can be re-initiated at that time, providing that the patient is not beyond day 14 of the cycle, in which case dosing would resume after the scheduled 7-day rest period. If the symptoms persist or appear during the rest period, dosing for the next cycle is delayed until symptoms have resolved to grade 0 or 1. Doses are adjusted as directed in the capecitabine package insert. While HFS is manageable, if left untreated it can progress rapidly. Reacting quickly to the signs and symptoms of HFS should prevent development of grade 2/3 symptoms and, therefore, reduce the impact on dose intensity. Nurses play a key role in educating the patient how to recognise HFS, when to interrupt treatment and giving instructions on adjusting the dose to maintain effective therapy with capecitabine over the long term. It is particularly important that patients and nurses are fully aware that dose interruption/reduction does not affect the overall antitumour efficacy of capecitabine (Cassidy and Twelves, 2000; Cassidy et al., 2002). Dose reduction after interruption of therapy Discontinuation of capecitabine usually leads to recovery over several days/weeks, depending on severity (Abushullaih et al., 2002). Following discontinuation, the guidelines for dose reduction should be the same as those applied to the general management of any adverse events occurring during capecitabine therapy (Table 3) and provided in the package insert. HFS tends to resolve rapidly, often without recurrence, but if it does recur and the patient is still benefiting from therapy, the physician may decide to change the treatment ARTICLE IN PRESS S36 Y. Lassere, P. Hoff 55-year old woman with MCRC Initiate treatment with oral capecitabine (1250 mg/m2 twice daily on days 1–14, every 3 weeks) 1st episode of grade 3 HFS OR 2nd episode of grade 2 HFS 1st episode of grade 2 HFS Interrupt capecitabine treatment Maintain Interrupt capecitabine treatment Maintain interruption interruption Does HFS resolve to grade 0/1? Does HFS resolve to grade 0/1? NO NO YES YES Reintroduce capecitabine Reintroduce capecitabine at 1250 mg/m twice daily at 1000 mg/m twice daily 2nd episode of grade 3 HFS OR 3rd episode of grade 2 HFS Discontinue drug permanently Interrupt capecitabine treatment OR Interrupt until resolved to grade 0/1 (at the discretion of the clinician) Maintain interruption Does HFS resolve to grade 0/1? NO YES 1st episode of grade 4 HFS OR Reintroduce capecitabine 3rd episode of grade 3 HFS at 625 mg/m twice daily Figure 2 Example of managing a patient with MCRC who develops HFS during treatment with capecitabine single-agent therapy. Table 3 Capecitabine dose-modification scheme for all adverse events. NCI-CTC toxicity grade Appearance of toxicity Adjustment during therapy Adjustment for next cycle (relative to initial dose) 2 1st 2nd 3rd 4th Interrupt until resolved to grade 0/1 Interrupt until resolved to grade 0/1 Interrupt until resolved to grade 0/1 Discontinue drug permanently 100% 75% 50% 3 1st 2nd 3rd Interrupt until resolved to grade 0/1 Interrupt until resolved to grade 0/1 Discontinue drug permanently 75% 50% 4a 1st Discontinue drug permanently or interrupt until resolved to grade 0/1b 50% NCI-CTC, National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria. a Not applicable to HFS. b At discretion of the clinician. cycle. An example would be increasing the interval between cycles to 2 weeks or changing the cycle length (e.g. 10 days on, 11 days off). When the guidelines for dose interruption and dose reduction are followed, hospitalisations are rare. In a recently presented study of capecitabine ARTICLE IN PRESS Management of hand-foot syndrome vs. 5-FU/LV (Mayo Regimen) as adjuvant therapy for patients with Dukes’ C colon cancer, only two capecitabine-treated patients required hospitalisation (for 1 day) (Cassidy et al., 2004b; Scheithauer et al., 2003). Supportive measures There are few supportive measures that have proven effectiveness in controlling symptoms. Use of topical emollients and creams would appear to be a prudent prophylactic and symptomatic treatment at the first signs of grade 1 HFS (Gerbrecht, 2003). Regular use of a topical petroleum-lanolin based ointment with antiseptic hydroxyquinoline sulphate applied 3-times daily has been reported to alleviate the symptoms of HFS induced by various chemotherapeutic agents (including capecitabine) (Chin et al., 2001). It should be noted that, anecdotally, some people are allergic to lanolinbased products. Nevertheless, dose interruption and, if necessary, dose reduction should remain the primary tool in HFS management. As a general recommendation, symptoms can often be relieved by: immersing the hands and feet in cool water avoiding extremes of temperature, pressure, and friction on the skin cushioning sore skin with soft pads topical wound care and consultation with a dermatologist for any blistering or ulceration (Gerbrecht, 2003). S37 et al., 1989, 1993). One study in dogs showed that prophylactic pyridoxine significantly delayed the onset and severity of HFS induced by liposomal pegylated doxorubicin, allowing a higher cumulative dose to be delivered (Vail et al., 1998). As pyridoxine is a safe nutritional supplement, its prophylactic use might appear appealing, although efficacy needs to be proven prospectively in controlled trials before routine treatment can be recommended. Such studies need to confirm no effect on capecitabine efficacy and whether effective prophylaxis might permit administration of a higher cumulative dose of capecitabine. An interesting adjunctive treatment with capecitabine might be concurrent use of celecoxib, a COX-2 antagonist used incidentally for control of pain and arthritis. In a retrospective series of 67 patients receiving capecitabine, the addition of celecoxib appeared to reduce the rate of HFS4grade 1 (from 34% with capecitabine alone to 13% with capecitabine plus celecoxib), as well as diarrhoea4grade 2 (from 29% to 3%) (Lin et al., 2002). However, in this series, most patients required dose reductions. This retrospective study has generated a hypothesis that needs to be tested in a prospective randomised setting. Until then, there is insufficient evidence to recommend the use of celecoxib in the prophylaxis of HFS. Conclusions Topical (Esteve et al., 1995; Gordon et al., 1995; Komamura et al., 1995; Vakalis et al., 1998; Vukelja et al., 1989) or systemic (Brown et al., 1991; Esteve et al., 1995; Hellier et al., 1996; Hoff et al., 1998; Titgan, 1997) corticosteroids have been reported to be useful for prophylaxis and treatment of HFS induced by a range of different drugs, although their use in capecitabine-associated HFS is unproven. While steroids are capable of reducing inflammation, their long-term use can lead to thinning of the skin, which is likely to cause more symptoms. Diemethysulfoxide 99% 4-times daily has been reported to be of benefit in patients receiving liposomal doxorubicin (Lopez et al., 1999) but is again unproven with capecitabineinduced HFS. The use of pyridoxine (vitamin B6), at a highly variable dose, has been anecdotally reported to be useful for prophylaxis and treatment of HFS induced by various agents, e.g. capecitabine, 5FU, docetaxel (Andres et al., 2003; Beveridge et al., 1990; Fabian et al., 1990; Lauman and Mortimer, 2001; Van Cutsem et al., 2000; Vukelja While HFS is a common and inconvenient side effect with capecitabine, the condition is easily managed with dose interruption and, if necessary, dose reductions. Prompt intervention means that patients do not need to interrupt treatment for long periods and can, therefore, continue to benefit from capecitabine therapy. Oncology nurses, through patient education and close clinical assessment, play a crucial role in the early identification and prevention of progressive pain, loss of the skin’s integrity, and disability. In addition, once HFS is identified, the nurses’ role in patient education, support, and symptom management is essential to maintain effective patient care and, in some cases, the patient’s willingness to continue therapy. Table 4 summarises some of the key preventative and management techniques for HFS. Patient education needs to highlight the need for reporting side effects and interrupting therapy when required. Written materials should be provided for the patient to reinforce the teaching ARTICLE IN PRESS S38 Table 4 Y. Lassere, P. Hoff Summary of preventative and management techniques for HFS. 1 Ensure patient is able to recognise HFS (and other adverse events) by education and use of written information available from the manufacturer or otherwise. 2 Recommend preventative emollient use (e.g. hand cream). 3 Ensure that the patient follows dose interruption/reduction guidelines carefully, which apply to all adverse events. Make sure the patient understands the importance of this prior to starting treatment and has written information available from the manufacturer or otherwise. 4 Ensure the patient has telephone access to a key person, e.g. oncology nurse, during office hours in the event of need to answer questions or concerns. 5 Follow up with the patient (by phone) to determine the outcome of HFS and provide other supportive advice. 6 Reassure the patient that there are no permanent complications once adverse events have resolved. 7 Advise patients to use topical emollients and creams to keep the skin moist. 8 Recommend patients to avoid extremes in temperature, pressure, and friction of skin. 9 Mention that relief can be achieved by submerging hands and feet in cool water. 10 Suggest cushioning sore skin with soft pads or socks and keeping the skin exposed to air whenever possible to prevent excess sweating. 11 Refer patients to a dermatologist if blistering or ulceration occurs. 12 As a last resort, if treatment is of benefit, change the dosing regimen. 13 Discontinue treatment if HFS is severe and unresolved by dose interruption/reduction. completed at clinic visits. These materials should incorporate: 1. Instructions on dosing, including how many tablets to take with each dose and information on the timing and importance of fluid intake with medication. 2. A diary or calendar to track dosing and side effects. 3. Reminders stressing the importance of calling promptly and interrupting treatment at the first signs of grade 2 toxicity. 4. Contact numbers for oncology nurses and physicians. These materials should be accompanied by weekly follow-up phone calls for the first few weeks of therapy to ensure that patients fully understand their role in reporting side effects and withholding therapy, as instructed. In conclusion, the nurses’ role in managing HFS in capecitabine-treated patients is pivotal for both its prevention and palliation. References Abushullaih, S., Saad, E.D., Munsell, M., Hoff, P.M., 2002. Incidence and severity of HFS in colorectal cancer patients treated with capecitabine: a single-institution experience. Cancer Investigation 20 (1), 3–10. Andres, R., Mayordomo, J.I., Isla, D., Yubero, A., Saenz, A., Alvarez, I., Polo, E., Lara, R., Escudero, P., Tres, A., 2003. Capecitabine plus gemcitabine is an active combination for patients with metastatic breast cancer refractory to anthracyclines and taxanes. Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 22, 89 (abstract 356). Arkenau, H.-T., Schmoll, H., Kubicka, S., Seufferlein, T., Reichardt, P., Freier, W., Graeven, U., Grothey, A., Porschen, R., 2004. Phase III trial of infusional 5-fluorouracil/folinic acid plus oxaliplatin (FUFOX) versus capecitabine plus oxaliplatin (CAPOX) as first line treatment in advanced colorectal carcinoma (ACRC): results of an interim safety analysis. Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 23, 257 (abstract 3546). Asgari, M.M., Haggerty, J.G., McNiff, J.M., Milstone, L.M., Schwartz, P.M., 1999. Expression and localization of thymidine phosphorylase/platelet-derived endothelial cell growth factor in skin and cutaneous tumors. Journal of Cutaneous Pathology 26 (6), 287–294. Baack, B.R., Burgdorf, W.H.C., 1991. Chemotherapy-induced acral erythema. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 24 (3), 457–461. Bellmunt, J., Navarro, M., Hidalgo, R., Sole, L.A., 1988. Palmarplantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome associated with shortterm continuous infusion (5 days) of 5-fluorouracil. Tumori 74 (3), 329–331. Beveridge, R.A., Kales, A.N., Binder, R.A., 1990. Pyridoxine (B6) and amelioration of hand/foot syndrome. Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 9, 102A (abstract). Blum, J.L., Smith, S.E., Buzbar, A.U., LoRusso, P.M., Kuter, I., Vogel, C., Osterwalder, B., Burger, H.U., Brown, C.S., Griffin, T., 1999. Multicenter phase II study of capecitabine in paclitaxel-refractory metastatic breast cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 17 (2), 485–493. Brown, J., Burck, K., Black, D., Collins, C., 1991. Treatment of cytarabine acral erythema with corticosteroids. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 24 (6), 1023–1025. ARTICLE IN PRESS Management of hand-foot syndrome Burgdorf, W.H.C., Gilmore, W.A., Ganick, R.G., 1982. Peculiar acral erythema secondary to high-dose chemotherapy for acute myelogenous leukemia. Annals of Internal Medicine 97 (1), 61–62. Cassidy, J., Twelves, C., 2000. Effective dose-modification scheme for the management of toxicities with capecitabine therapy: data from metastatic colorectal cancer phase III trials. Capecitabine CRC Study Group. Annals of Oncology 11 (Suppl. 4), 62 (abstract 271PD). Cassidy, J., Twelves, C., Van Cutsem, E., Hoff, P., Bajetta, E., Boyer, M., Bugat, R., Burger, U., Garin, A., Graeven, U., McKendrick, J., Maroun, J., Marshall, J., Osterwalder, B., Pe´rez-manga, G., Rosso, R., Rougier, P., Schilsky, R.L., on behalf of the Capecitabine Colorectal Cancer Study Group, 2002. First-line oral capecitabine therapy in metastatic colorectal cancer: a favorable safety profile compared with intravenous 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin. Annals of Oncology 13, 566–575. Cassidy, J., Tabernero, J., Twelves, C., Brunet, R., Butts, C., Conroy, T., DeBraud, F., Figer, A., Grossmann, J., Sawada, N., Scho ¨ffski, P., Sobrero, A., Van Cutsem, E., Dı´az-Rubio, E., 2004a. XELOX (capecitabine plus oxaliplatin): active first-line therapy for patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 22, 2084–2091. Cassidy, J., Twelves, C., Nowacki, M.P., et al., 2004b. Improved safety of capecitabine versus bolus 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin (LV) as adjuvant therapy for colon cancer (the X-ACT phase III study). Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium (abstract 219). Chin, S.F., Tchen, N., Oza, A.M., Moore, M.J., Warr, D., Siu, L.L., 2001. Use of ‘‘bag balm’’ as topical treatment of palmarplantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome in patients receiving selected chemotherapeutic agents. Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 20 (abstract 1632). D’Agostino, G., Ferrandina, G., Ludovisi, M., Testa, A., Lorusso, D., Gbaguidi, N., Breda, E., Mancuso, S., Scambia, G., 2003. Phase II study of liposomal doxorubicin and gemcitabine in the salvage treatment of ovarian cancer. British Journal of Cancer 89, 1180–1184. de Gramont, A., Figer, A., Seymour, M., Homerin, M., Hmissi, A., Cassidy, J., Boni, C., Contes-Fures, H., Cervontes, A., Freyer, G., Papamichael, D., Le Bail, N., Louvet, C., Herdler, D., de Braud, F., Wilson, C., Morvan, F., Bonetti, A., 2000. Leucovorin and fluorouracil with or without oxaliplatin as first-line treatment in advanced colorectal cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 18, 2938–2947. Diasio, R.B., 1998. Dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase modulation in 5-FU pharmacology. Oncology 12 (Suppl. 7), 23–27. Douillard, J.Y., Cunningham, A., Roth, A.D., Navorro, M., James, R.D., Korasek, P., Jandik, P., Iveson, T., Carmichael, J., Alakl, M., Gruia, G., Awad, L., Rougier, P., 2000. Irinotecan combined with fluorouracil compared with fluorouracil alone as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet 355 (9209), 1041–1047. Esteve, E., Schillio, Y., Vaillant, L., Bensaid, P., Missonnier, F., Metman, E.H., Lorette, G., 1995. Efficacite ´ de la corticothe ´rapie se´quentielle dans un cas d’e ´rythe `me acral douloureux secondaire au 5-fluoro-uracile `a fortes doses. Annales de Medecine Interne (Paris) 146 (3), 192–193. Fabian, C.J., Molina, R., Slavik, M., Dahlberg, S., Giri, S., Stephens, R., 1990. Pyridoxine therapy for palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia associated with continuous 5-fluorouracil infusion. Investigational New Drugs 8 (1), 57–63. Gerbrecht, B.-M., 2003. Current Canadian experience with capecitabine. Cancer Nursing 26 (2), 161–167. S39 Gieschke, R., Reigner, B., Blesch, K.S., Steiner, J.-L., 2002. Population pharmacokinetic analysis of the major metabolites of capecitabine. Journal of Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics 29 (1), 25–47. Gieschke, R., Burger, H.U., Reigner, B., Blesch, K.S., Steimer, J.L., 2003. Population pharmacokinetics and concentrationeffect relationships of capecitabine metabolites in colorectal cancer patients. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology 55 (3), 252–263. Gordon, K.B., Tajuddin, A., Guitart, J., Kuzel, T.M., Eramo, L.R., VonRoenn, J., 1995. HFS associated with liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin therapy. Cancer 75 (8), 2169–2173. Hellier, I., Bessis, D., Sotto, A., Margueritte, G., Guilhou, J.J., 1996. High-dose methotrexate-induced bullous variant of acral erythema. Archives of Dermatology 132 (5), 590–591. Hoff, P.M., Valero, V., Ibrahim, M., Willey, J., Hortobagyi, G.N., 1998. HFS following prolonged infusion of high doses of vinorelbine. Cancer 82 (5), 965–969. Ishikawa, T., Utoh, M., Sawada, N., Nishida, M., Fukase, Y., Sekiguchi, F., Ishitsuka, H., 1998. Tumor selective delivery of 5-fluorouracil by capecitabine, a new oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate, in human cancer xenografts. Biochemical Pharmacology 55 (7), 1091–1097. Jucgla, A., Sais, G., 1997. Diagnosis in oncology: HFS. Journal of Clinical Oncology 15 (9), 3164. Komamura, H., Higashiyama, M., Hashimoto, K., Takeda, K., Kimura, H., Tani, Y., Ogawa, H., Yoshikawa, K., 1995. Three cases of chemotherapy-induced acral erythema. Journal of Dermatology 22 (2), 116–121. Kroll, S.S., Koller, C.A., Kaled, S., Dreizen, S., 1989. Chemotherapy-induced acral erythema: desquamating lesions involving the hands and feet. Annals of Plastic Surgery 23 (3), 263–265. Lauman, M.K., Mortimer, J., 2001. Effect of pyridoxine on the incidence of palmar plantar erythroderma in patients receiving capecitabine, Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 20 (abstract 1565). Leo, S., Tatulli, C., Taveri, R., Campanella, G.A., Carrieri, G., Colucci, G., 1994. Dermatological toxicity from chemotherapy containing 5-fluorouracil. Journal of Chemotherapy 6 (6), 423–426. Lin, E., Morris, J.S., Ayers, G.D., 2002. Effect of celecoxib on capecitabine-induced HFS and antitumor activity. Oncology 16 (12 Suppl. 14), 31–37. Lokich, J.J., Moore, C., 1984. Chemotherapy-associated palmarplantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome. Annals of Internal Medicine 101 (6), 798–799. Lopez, A.M., Wallace, L., Dorr, R.T., Koff, M., Hersh, E.M., Alberts, D.S., 1999. Topical DMSO treatment for pegylated liposomal doxorubicin-induced palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia. Cancer Chemotherapy and Pharmacology 44 (4), 303–306. Meta-Analysis Group in Cancer, 1998. Toxicity of fluorouracil in patients with advanced colorectal cancer: effect of administration schedule and prognostic factors. Journal of Clinical Oncology 16 (11), 3537–3541. Miwa, M., Ura, M., Nishida, M., Sawada, N., Ishikawa, T., Mori, K., Shimma, N., Umeda, I., Ishitsuka, H., 1998. Design of a novel oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate, capecitabine, which generates 5-fluorouracil selectively in tumours by enzymes concentrated in human liver and cancer tissue. European Journal of Cancer 34 (8), 1274–1281. Mrozek-Orlowski, M.E., Frye, D.K., Sanborn, H.M., 1999. Capecitabine: nursing implications of a new oral chemotherapeutic agent. Oncology Nursing Forum 26 (4), 753–762. Nagore, E., Insa, A., Sanmartı´n, O., 2000. Antineoplastic therapy-induced palmar plantar erythrodysesthesia ARTICLE IN PRESS S40 (‘hand-foot’) syndrome: incidence, recognition and management. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology 1 (4), 225–234. Ng, J.S., Cameron, D.A., Leonard, R.C., 1994. Infusional 5fluorouracil in breast cancer. Cancer Treatment Reviews 20 (4), 357–364. O’Shaughnessy, J., Miles, D., Vukelja, S., Moiseyenko, V., Ayoub, J.P., Cervantes, G., Fumoleau, P., Jones, P., Liu, W.Y., Mauriac, L., Twelves, C., van Hazel, G., Verma, S., Leonard, R., 2002. Superior survival with capecitabine plus docetaxel combination therapy in anthracycline-pretreated patients with advanced breast cancer: phase III trial results. Journal of Clinical Oncology 20 (12), 2812–2823. Park, Y.H., Ryoo, B.Y., Lee, H.J., Kim, S.A., Chung, J.H., 2003. High incidence of severe HFS during capecitabine-docetaxel combination chemotherapy. Annals of Oncology 14 (11), 1691–1692. Patt, Y.Z., Liebmann, J., Diamandidis, D., Eckhardt, S.G., Javle, M., Justice, G.R.W., Keiser, W., Lee, F.C., Miller, W., Lin, E., 2004. Capecitabine (X) plus irinotecan (XELIRI) as first-line treatment for metastatic colorectal cancer (MCRC): Final safety findings from a phase II trial. Proceedings of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 23, 271 (abstract 3602). Scheithauer, W., McKendrick Jr., J., Begbie, S., Broner, M., Burns, W.I., Burris, H.A., Cassidy, J., Jodrell, D., Koralewski, P., Levine, E.L., Marschner, N., Maroun, J., Garcia-Alfonso, P., Tujakowski, J., van Hazel, G., Wong, A., Zaluski, J., Twelves, C., for the X-ACT Study Group, 2003. Oral capecitabine as an alternative to i.v. 5-fluorouracil-based adjuvant therapy for colon cancer: safety results of a randomized, phase III trial. Annals of Oncology 14 (12), 1735–1743. Y. Lassere, P. Hoff Sternberg, C.N., Reichardt, P., Holland, M., 2004. Development of and Clinical experience with capecitabine (Xelodas) in the treatment of solid tumours. European Journal of Oncology Nursing 8 (Suppl. 1), S4–S15. Titgan, M.A., 1997. Prevention of palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia associated with liposome-encapsulated doxorubicin by oral dexamethasone. Proceeding of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 16, 82A (abstract). Vail, D.M., Chun, R., Thamm, D.H., Garrett, L.D., Cooley, A.J., Obradovich, J.E., 1998. Efficacy of pyridoxine to ameliorate the cutaneous toxicity associated with doxorubicin containing pegylated (Stealth) liposomes: a randomized, doubleblind clinical trial using a canine model. Clincal Cancer Research 4 (6), 1567–1571. Vakalis, D., Loannides, D., Lazaridou, E., Mattheou-Vakali, G., Teknetzis, A., 1998. Acral erythema induced by chemotherapy with cisplatin. British Journal of Dermatology 139 (4), 750–751. Van Cutsem, E., Findlay, M., Osterwalder, B., Kocha, W., Dalley, D., Pazdur, R., Bassidy, J., Dirix, L., Twelves, C., Allman, D., Seitz, J.F., Scholmerich, J., Burger, H.U., Verweij, J., 2000. Capecitabine, an oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate with substantial activity in advanced colorectal cancer: results of a randomized phase II study. Journal of Clinical Oncology 18, 1337–1345. Vukelja, S.J., Lombard, F.A., James, W.D., 1989. Pyridoxine therapy for palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome. Annals of Internal Medicine 111 (8), 688–689. Vukelja, S.J., Baker, W.J., Burris III, H.A., Keeling, J.H., von Hoff, D., 1993. Pyridoxine therapy for palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia associated with Taxotere. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 85 (17), 1432–1433.

© Copyright 2026